This is the theological continuation of the philosophical beginning in The Resplendent Completion of the Liberal Arts.

Catholic Theology and the Beginning

In the beginning. Theology begins at a beginning. Well, it begins at more than one beginning, but we will begin with the first. So: in the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth . . .[1] God created everything above and everything below, and created even this beginning. There is a “before” creation, a before the beginning, but there is no word for it—it is not a before, not like a time with an after, not at all, since there is only “after” the beginning—and it is not really known in itself, known as it is only through the beginning. There was no beginning, and then there was. God created ex nihilo, out of nothing.[2] All that is “something”: God created that.

To put it another way: there is that which does not begin, does not, and there is that which begins beginnings. This is God. God simply is. God has no beginning. God is always. Not forever: that would suggest some stretch of time. Some endless stretch. God is neither beginning nor end, not even endlessness. God is. God simply is.[3] And God creates; God is Creator. All that is, everything, has its origin in the God without origin: all that is, from the God who simply is. Theology begins here, with the Creator. With this One about whom it is so hard to have words at all.

What is unique about the Christian understanding of God is not that God is Creator, but the way this is understood. We need to know this: God did not have to create. Nothing forces God’s hand. God does not need what he creates; rather, God freely chooses to create. This choice, this utterly free decision—it did not even have to be made—is an expression of God’s goodness. The entirely free God is entirely good. So then: God creates from the purest, most infinite freedom, out of the Goodness that gives existence as the purest gift.[4] For the Christian, everything that is, is a pure gift. That which exists does so because God wants it to exist. This is a radical freedom that God has. Creation emerges from the decision of a radical freedom. Not an arbitrary freedom, but a good one.

I am saying this: existence is a gift. Every bit of it. The first meaning of the Christian world is “gift,” and it is a meaning seen in every detail. This gift-quality of the world is seen unfurling in every passing cloud, in every human face, in every scientific question. Everything has an origin in God. Not directly, because creation has its own way of being; and yet, not indirectly, because this way of being has God as its primary cause.[5] What I mean is this: the gift of existence is really given, which means it is really ours, and still every breath we take is God giving the gift again. Every man is but a breath,[6] a breath given by God. Both dignity and fragility in the same created being. This breath of God is also “spirit.” There is a spirit in human beings, the breath of the Almighty, that gives them understanding.[7] This spirit is what makes human beings knowers of meaning: asking, acting, giving in our own ways. The gift of existence is itself a radical freedom, one that is really ours. We have a freedom that is eerily like the Creator’s freedom, yet not at all infinite.

So we see that the meaningfulness of the world is marked everywhere as a gift. This means in one way that the world is everywhere marked by God, and so offers the further gift not only of its own existing, but also of allowing us to know something of its Giver.[8] The gift of existence means in another way that the world is everywhere “not-God,” that the gift is not the same as the Giver.[9] God is neither in the world nor identical with it. God is transcendent, a theologian might say. That is, God is not within the world or above the world or behind or beneath; there is no “where” that God is, just as there is no before or after: God, invisible and immaterial, is nowhere and everywhere.

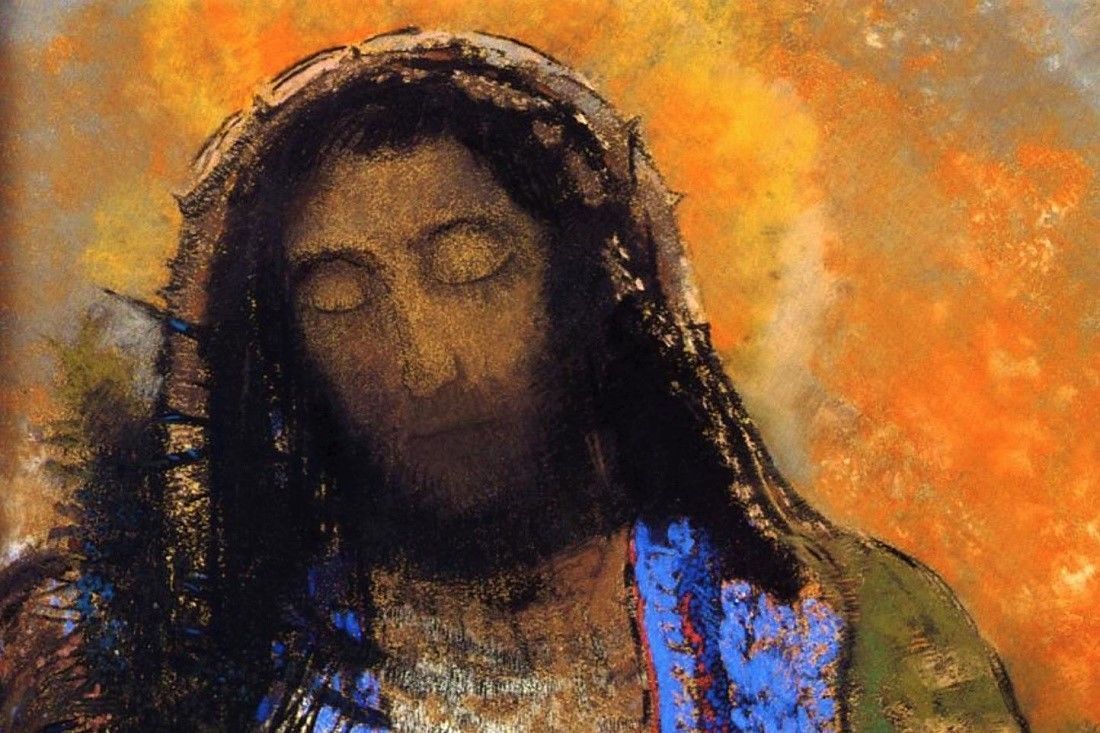

It is perhaps confusing, if not vexing, as I continually pair affirmations about God with a vociferous series of negations. It is hard to speak of this God, to dare to speak of God at all. The God whose name cannot even be said.[10] Theology is a way—not a method, not a technique—that walks the dangerous path of saying true things about God (theos–logia). It is primarily a way of mystery. By this I mean not that God is half comprehended or entirely uncomprehended, nor even that God is a question to be answered. God is holy, that is, set apart. This means that God will always outstrip human words. Affirmations are always followed by negations. God is as we say, and God is not as we say. In mystical theology, the highest theology, kataphatic (affirmative) knowing is followed by apophatic (negating) knowing, and finally the two are united in the mysterious union of God and human being called “illumination.”[11] This is a light that surpasses all light, and sometimes it is called the “divine darkness,” the “unknowing knowing,” the “luminous darkness.” Moses knew this in the dark and fire of Mount Sinai, where he saw God but not the face of God.[12]

God chose to create all that is. Existence is gift. God is mystery. Existence, too, is therefore mystery.

Now, theology has another beginning (and this is really where theology secretly, simultaneously, always began and begins): In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God.[13] Who is this Word? He is Light. The light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.[14]Why would we care? The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us, and we saw his glory.[15] The Word, who is God, became one of us.

Jesus is God incarnate.[16] In flesh. Here is where we turn our eyes with theology or cease looking entirely. This is a point of difference with many people of many different traditions, and I will not name it otherwise. Still: follow me a little down the way, and I will show you what it means to see with the eyes of theology.

Jesus is God, fully God; and Jesus is man, fully man. He is like us in every way but sin (and therefore more human). He is like God in every single way, but not Father. Jesus is someone. Jesus is someone particular, you see. He is a human being, entirely, and not in a generic way: no, he was and is a specific man who lived in a specific time and in a specific place. He is God, entirely (ὁμοούσιος, consubstantia), and he is specifically Son.

The Son is a person. Christianity literally invents the word, creates a new word out of an old one (ὑπόστασις). In order to describe who, specifically, Jesus is—not Father, not Spirit, but Son; and fully divine; and God is one—the answer comes as the Person of the Son. Who is Jesus? He is the Son, the divine Son. The Person. Whose divinity do we know in the flesh? The Son’s. Whose flesh suffers on the cross? The Son’s. Jesus is someone, and so being someone comes to matter in incredible new ways with the rise of Christianity. The human person is named and loved as an indispensable gift. Every human person, loved and indispensable. Why? Because God became one of us. God cares. God wants us. Each of us. Enough to be someone with us.

Christianity therefore has a keen awareness of what is particular. It sees every little thing as a particular gift, unforgettable and unique. Matter, too, is reverenced, reverenced because it is by flesh that the world is redeemed and through it that God is known.[17] God is still not in the world, but God has entered it by becoming a human being. God is still nowhere-and-everywhere, but God also became someone from somewhere. The vast, inconceivable luminous dark suddenly has a face. The world is the same, and not the same at all. God has walked in the dust of his earth with our feet.

Theology begins with this paradoxical marriage of what is finite with what is infinite in Jesus Christ. The invisible, immaterial God has been seen in the flesh. God’s incredible freedom (remember: God cannot be forced) reveals itself as incomprehensible love. Now, the wonder of the Incarnation gestures toward a darkness. The light shines in the darkness. That darkness is named in various ways: evil, powers and principalities, violence, sin. It means that the world is broken, that not all is as it should be, somehow. We suffer.

So the loving God suffers in the flesh in order to redeem it. Impossibly, one of the Trinity has suffered.[18] This is sometimes called the “wonderful exchange,” the admirabile commercium.[19] By sharing in all that we are, God shares all that He is. “Salvation” is this exchange. Yes, a rescue from something awful, but more seriously a making-whole, a making more human. A making into a human who dares approach the divine through the Spirit of the One who approaches us.

I am saying that the narrative of guilt-and-redemption cannot be understood outside of a narrative of divine love. This narrative is not really a story, but a sharing in the divine love itself. That is, faith is necessary to really know this love, because it is faith that knows with God. Here I do not mean that faith is irrational, but rather that it is supra-rational. It is a gift (a grace, which means “gift”) that enables freedom and knowledge in new ways. The same powers of human being are perfected and elevated, not destroyed. Faith sees in new ways with the same eyes. Theology cannot live without faith—credo ut intelligam[20]—even as it does not live according to faith alone. In other words: I cannot prove the Incarnation to you, and I would not consider that possible. But I could show you its reasonableness, its possibility, which I nevertheless do in light of my faith in it. If we do not share faith, still we will always share reason. Always.

Nor can this reality, the reality of God, be understood outside of a community, a sharing. Christians believe, and always together. Personal faith is valued, but there is in Catholicism no word for individual faith. That is, faith apart from others. Faith is shared, and so we will often find Catholics setting themselves at a distance from each other and yet always concerned to relate to one another. They are never ultimately apart from each other, or they cease sharing all that is Catholic.

Really what I mean is that Catholicism, that it in particular, is deeply liturgical. I mean that it centers on ritualized actions done before God and with God. Liturgy is very material, very “in the flesh,” with many sights and sounds and words. We cannot even sit still at the Mass. There is bowing, standing, embracing. All so very bodily, and for the God who made for himself a body. The liturgy is very particular, focused always on that one death and that one resurrection (that dying and that new living, by one and for all). Concentrated always on the Persons of the Trinity. The liturgy is not the work of God in general, but the work of the Spirit in the Son for the Father. That is to say, the liturgy is and is the summary of all that Catholicism is. The liturgy is always together, human beings and the Trinity together, and never apart. The Eucharist – which is Jesus himself, entirely - is both the source and summit of Christianity.[21] It is the most particular, most generous, most free gift of God to humanity: the gift that is God.

Liturgy is formative. Western monasticism is an especially helpful example of liturgical formation. It is a way of life far more than it is a set of discursive principles and skills. “Incline the ear of your heart,” the Rule of Benedict says to its monks, and “run the way of God's commandments with unspeakable sweetness of love.”[22] The monk first listens, first attends in liturgy; then runs, rushes along a path that seeks good work, a path sent forth from the liturgy and that curves back to liturgy again and again. Leaving and returning; working and praying;[23] outward and inward, like the very breath of Christ.[24] All is done out of love, out of loving attention to Christ. “We must prepare our hearts and our bodies,” the Rule insists, and in this sentiment we see finally how nothing less than the very depths of the human person, heart and body and all, is what loves God in the liturgy. This is what I mean by formation: the entire human person enlivened and offered to God in continual praise. The more whole the person becomes, the more wonderful the act of offering. And always, God is already there, already listening, already sanctifying: “My eyes shall be upon you and My ears open to your prayers [and] before you call upon Me, I will say to you, 'Behold, here I am'"[25]

Catholic Theology and the Liberal Arts

What then of the liberal arts? How, then, does Catholicism turn its profoundly Christocentric gaze to these ancient disciplines? The answer is on the one hand rather ordinary, and on the other rather liturgical. It helps us to know why Catholics would, paradoxically, need and even adore the presence of non-Catholics at their institutions, and yet stand in painful need of Catholics—nor even just any Catholic, but knowledgeable ones—at their institutions. That is, they welcome those who know in many ways all while bearing a Catholic faith that knows in ways that no other way does.

If grace perfects nature and does not destroy it, if God became man, then all that is natural and human is good. All of it might glorify God. So why not the liberal arts? Surely these, too, might be perfected and lifted in an offering to God. There is a very simple way in which what is good is simply good. It is as child-like as that.

Everything that I said about meaning, every inch of the prologue, is considered the case in Catholic thought. The incredible pluriformity of truth testifies to the wonder of creation, and each truth in its own way indicates the wonder of its Creator. Catholics do not see this diversity as a contradiction, but as the flourishing of God’s own creativity. Therefore only that which is true, that which really is, is sought and delighted in. Diversity enriches, which also means that it does not negate what is different than it. Instead, every intelligible difference indicates the luminous darkness of a wholeness not to be found in itself. A wholeness to be found only in God, in the Word (Λόγος, Logos) who became flesh.

Long ago, Christian theology borrowed from Stoic philosophy in order to describe what Stoicism itself never claimed. Theology, caught between God and the world, is the consummate borrower: any element of the diverse creation is used in a new way to speak of the Creator. Through Stoicism, then, early Christian theologians described the many and diverse truths or words (logoi) of the world. These “words” were called “seeds” of the one Word (logos spermatikos) in whom all things had been created, that is, in the Word that all other words resembled. Again, creation does not resemble God in a general way, but specifically: creation resembles the Word. The “image” of God is found everywhere; vestiges of the Trinity are in all things, especially in human beings.[26]

One of the primary similarities between human beings and God is one to be found between the Trinity and the human mind. As the human mind has indivisible yet distinguishable powers (memory, intellect/understanding, will) so in a similar but more mysterious way God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: indivisible yet distinguishable. Long after early Stoic traditions had been borrowed, Augustine borrowed from Platonic thought in order to describe the immense mystery of the Trinity. Still, this “psychological analogy” of his remains an analogy, and God remains ever greater than all that might be said of him.

What is genius in Augustine’s achievement is not merely the use of what is old to say something new, indeed to say something profound about God, which he does do; rather, his achievement rests in the idea that all human knowing imitates the Trinity itself. Every question asked, every meaning discerned, every understanding judged true: not only does the true and the meaningful resemble God, but so do the acts of asking, the discerning, and the judging. Every single act of the mind, even if done badly, but especially if done well: every act is an image the Trinity itself. The liberal arts are, suddenly, works of the mind that resemble the secret Heart of God. They are still themselves, and yet more. Indeed, the wisdom of the Holy Spirit, the Holy Spirit that is Wisdom itself, enables in us a new and supernatural wisdom, one that sees all things with the eyes of God, for the Spirit is God. The Christian, in knowing even the simplest thing, sees it anew. Sees with the mystery of God through God himself: For the Spirit scrutinizes everything, even the depths of God.[27]

And this Heart of God is secret; there is no getting around that. This is the mystery hidden from ages past in God who created all things.[28] No one can stumble into the Trinity by an accidentally perfect mathematical proof. It is faith that sees the eternal God in the geometry. Nor would faith see at all if God did not first give faith as a gift, if God did not first act. This is a difficult thing: God must make himself known, his inner self, or the Trinity is never known at all. With Christianity we have a God who acts, a God who intervenes. A Word who wraps himself in the flesh of our little words, who speaks the words himself in order to speak himself. He did this just as you and I do—acting and speaking to express ourselves—and not at all as you and I do. I am an image of the Word, but I am not the Word. Jesus: he is the Word.

Catholics sometimes see themselves as running out into the world searching for every single word about the Word, drawing these words into frail hands in order to give them back again to God. Every task of knowledge is in service of this priestly act of offering everything back again to the God who already gave everything. The fullness of all knowledge is worship; the most liberal act is offering words of praise. There can be no utility, no domination, no violence when words are transfigured into authentic praise.

What was a “way” of knowing in the original liberal arts is now a pilgrimage to see the face of God. My soul thirsts for God, the living God. When can I enter and see the face of God?[29] The pilgrimage is to and with Christ, who is the face of God. Nor is this pilgrimage walked alone, just as faith itself is never lived alone. This is always done with others: fellow Catholics, and fellow human beings. If it is a word, any word, it is for the Word. So in the very middle of their most radical absolute claims, Catholics always make a claim for radical tolerance. If it is a word, any word, it is for the Word. Not the nonexistent words, the lies, but the truths: every single one of them brings us nearer to God. No matter who says the truth. And yet, at the same time Catholics must always be reverencing exactly who says it: this is someone, an unrepeatable Person who speaks, the Son who resembles God the Father as no one else ever will. For just as the Father has life in himself, so also he gave to his Son the possession of life in himself.[30]

There is something especially fitting or beautiful about the liberal arts in the arms of Christianity. Inasmuch as the liturgy is formative, so the formation that is the various liberal arts arrive to complement a way of life that is already devoted to being formed. The liberal arts appear as a further instrument of formation, a sharpening of the mind that wishes to know God. The mind that wishes to ask questions about God (and there are so many questions about God). Anything that will enlighten the spirit desiring God is wonderful, and the liberal arts are especially so. Especially because, in their own way, they already illuminate.

The light of the liberal arts is different in the light of faith. The Christian formed by the liturgy is, really, the bearer of a new reality: the reality of Christ. The very realness of Christ becomes the Christian’s own reality. (We move past formation here.) As the personal bearer of this personal reality, the Christian transfigures everything that he or she touches. Sometimes this difference is hidden even to the Christian; sometimes it is clear and shining and other. Even without mentioning Jesus, still the Christian in his or her own flesh participates in him. Everything that the Christian does therefore becomes an offering to God with the Son in the Spirit. Everything is a miniature liturgy, and suddenly Christian existence shines as a fractal one, with the identical image radically contained in every other image of every magnitude and every infinitesimal scale.

I mean that, as with freedom and reason, the instrument of the liberal arts is the same and yet not the same. The difference is the divine gift. Theology is the height of the liberal arts, their completion, but only as a grace – a perfection that does not destroy. Catholicism is drawn to the liberal arts for all their incisive particularity, and through them Catholicism is able to seek both the world and the God who made it. Out of love, Christians seek truths and Truth, and seek to be made different through the seeking itself.

There is in us a certain distance between the truth that we are and the true things that we say. In God, the Father and Son are one Spirit: distinguishable, but wholly one. There is no distance here. God is Truth. And this Truth, the Truth of the Father that the Word is, became flesh and spoke in the Spirit of Truth of himself, in the truth our words. There is no distance between the Truth that He is and the Truth that He speaks. He is the unconfused union[31] of every diverse truth (logoi) and the True (Logos). To put it simply: God is honest; He is as He says.

If God tells us who he is without reserve, then this is a gift without measure. A literally measureless gift.[32] Yet there is a further gift in this wonderful exchange, one that transfigures the nature of all knowing – makes it honest in a new way. The further gift is that I might speak the truth of myself in Truth, in spirit and truth.[33] Every Christian is a witness (marturion, martyr) who speaks him or herself in the Spirit and the Word (Truth). In this Spirit, there is no longer any distance between the speaker and the spoken: so Christians see their whole lives, every act, as a martyrdom, as a sacrament of the truth. Primarily this is bloodless, this living and speaking. Mostly it involves acts of peace and poverty and love. Acts of asking and knowing and sharing. Let your Yes mean Yes and your No mean No.[34] Yet always these things are done with the testimony of one’s whole self, every drop of one’s blood – to the point that the Christian would rather shed blood than deny this wholeness of self, of world, of God. This includes the wholeness of all that is, of all that you are. The Christian ought rather die than deny it, including the truth that you are – no matter if you are enemy, or friend, or stranger. Do you see the paradox here? The unique unwillingness to forget uniqueness, the universal embrace of all that is particular?

“Catholic” means universal, after all. And this is not a general universe. It is a specific one. One made through the Word, the Word who became flesh, the Word of all little words . . . And here I return from where I began, returning again to where everything begins and ends. The Christian is endlessly leaving and returning, as from an eternal liturgy. Nor is it just any liturgy, but a specific one, the one that says Yes. Yes to what God wants to be. A free Yes to God’s good plan. Like that young Jewish woman, long ago . . . That specific woman, with a specific name . . . Mary . . . Who said Yes, and Word became flesh . . .

[1] Genesis 1:1. Translation used: NABRE.

[2] This is an essential and very early Christian claim, distinct from the original context of Genesis, and a key Christian reinterpretation of that same text. See Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975).

[3] God is “Pure Act” according to Thomas Aquinas: Summa Theologica, Prima Pars Q. 3 a. 2.

[4] See Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Drama: Theological Dramatic Theory, vol. 2: The Dramatis Personae, Man in God, trans. Graham Harrison (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990).

[5] Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Prima Pars Q. 44 a. 1, 3, 4.

[6] Psalm 39:6

[7] Job 32:8

[8] “All beings know God implicitly in whatever they know.” Thomas Aquinas, De veritate, Q. 22, a. 2. See also Balthasar, Theo-Logic, 52.

[9] Hans Urs von Balthasar, “On the Tasks of Catholic Philosophy in Our Time,” trans. Brian McNeil, Communio 20 (1993): 147-187; “The Fathers, the Scholastics, and Ourselves” Communio 24 (1997): 347-396.

[10] See Exodus 3:15

[11] See Pseudo-Dionysius the Aeropagite, The Complete Works, trans. Paul Rorem (New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1988).

[12] Exodus 33:18-23

[13] John 1:1-2

[14] John 1:5

[15] John 1:14

[16] Here I pass over a significant amount of history between the Gospel of John and my statement. I only acknowledge that here.

[17] See, for example, John of Damascus, Three Treatises on the Divine Images, trans. Andrew Louth (New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003). “Of old, God the incorporeal and formless was never depicted, but now that God has been seen in the flesh and has associated with human kind, I depict what I have seen of God. I do not venerate matter, I venerate the fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation, and I will not cease from reverencing matter, through which my salvation was worked” (29).

[18] Cyril of Alexandria, On the Unity of Christ, trans. John Anthony McGuckin (New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1995), 117-118.

[19] O Admirabile Commercium is an ancient Christmas season antiphon in Christianity.

[20] This phrase can be found in both Anselm’s Cur deus homo and Augustine’s Sermon 43 (credo ut intelligas).

[21] Lumen Gentium, The Second Vatican Council (Vatican City: November 21, 1964), §11.

[22] Rule of Benedict, trans. Leonard Doyle, “Prologue.” Available online thanks to the Order of Saint Benedict: http://www.osb.org/rb/text/rbejms1.html#pro.

[23] Ora et labora, “prayer and work,” the coda of the Benedictines.

[24] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World, trans. Erasmo Leiva (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1979), 29: “If you were once fully yourself, you would live solely on this gift that flows out of you (this gift which you yourself are), and you would do this by giving it away in turn, in holiness without having defiled it through possessiveness. Your life would be like breath itself, like the lungs’ calm and unconscious double movement. And you yourself would be the air, drawn in and exhaled with the changing measure of the tides. You would be the blood in the pulse of a Heart that takes you in and expels you and keeps you captive in the circulation and spell of its veins.”

[25] Ibid.

[26] This idea is discernable especially in Bonaventure’s Itinerariam mentis in Deum, Hugh of St. Victor’s De Sacramentis Christianæ Fidei, Augustine’s De Trinitatae.

[27] 1 Corinthians 2:10

[28] Ephesians 3:9

[29] Psalm 42:3

[30] John 5:26

[31] Definition of the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD): “So, following the saintly fathers, we all with one voice teach the confession of one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ: the same perfect in divinity and perfect in humanity, the same truly God and truly man, of a rational soul and a body; consubstantial with the Father as regards his divinity, and the same consubstantial with us as regards his humanity; like us in all respects except for sin; begotten before the ages from the Father as regards his divinity, and in the last days the same for us and for our salvation from Mary, the virgin God-bearer as regards his humanity; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only-begotten, acknowledged in two natures which undergo no confusion, no change, no division, no separation; at no point was the difference between the natures taken away through the union, but rather the property of both natures is preserved and comes together into a single person and a single subsistent being; he is not parted or divided into two persons, but is one and the same only-begotten Son, God, Word, Lord Jesus Christ, just as the prophets taught from the beginning about him, and as the Lord Jesus Christ himself instructed us, and as the creed of the fathers handed it down to us.” (This translation copyright EWTN 1996. Emphasis mine).

[32] Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, trans. Matthew D. Waltz (Southbend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2013), 32-33: “My understanding is not able with respect to this light. It shines too brightly . . . It is beat back by its brightness, it is conquered by its ampleness, it is overwhelmed by its unmeasuredness . . . You are present everywhere as a whole, and I do not see you. In you I move and in you I am, and I am not able to approach you. You are within me and around me, and I do not sense you.”

[33] John 4:24

[34] Matthew 5:37