Leisure is not the cessation of work, but work of another kind, work restored to its human meaning, as a celebration and a festival.

–Roger Scruton

Leisure may very well be the basis of culture—as the beloved Josef Pieper says—but the word bears a fantastically unconvincing ring to a family full of farmers and maintenance workers as something to do with one’s life. I can assure you of this from personal experience. When the leisure espoused includes nary a game of sport or hunting, and includes little to no gambling, you can understand the incommensurable impasse a fly-over humanities major finds himself in defending their life choices. The great Walker Percy on more than one occasion relates that it was easier to say to townsfolk in Louisiana that he did “nothing” rather than explain that he wrote for a living.

My interest is drilling into a fundamental misunderstanding of leisure by its supposed practitioners and most fervent devotees. Too often the allure of the quietude and unsegmented hours that must be allotted for the practice of leisure seem to be an endgame or goal all on their own. It begins to be obvious why a working class parent might see leisure as a complicated excuse to be lazy, to do nothing, to have no cares. And insofar as the proponents of leisure act as if the listless hours and solemn noiselessness are an end in themselves, said parent has a point. It seems to me that the practitioner of leisure whom has never found him or herself sufficiently terrified of the result of their leisure is properly lambasted by the workman, for they have ignored the craft of which they claim to be artisans. Terror you might ask? Let me explain, and with no less than Josef Pieper to make my point.

First of all, a ready admission: the necessary role of leisure for prayer and contemplation are not under siege in this essay. Others, far holier and contemplative than I, have expounded their merits and have made the case of leisure’s necessity for both, elsewhere. Nor will I bring an argument to bear on the great necessity of festival as outline by Pieper in multiple places. Instead, I want to focus on what I will call the fruits of leisure, and to begin with a practical enough example. Let us consider something close at hand: this article. Certainly I took my leisure to write this article—set aside “free time,” read, thought, etc.—and this essay is hopefully a ready enough example as to the product a craftsman such as I should produce. But additionally, I must quickly disabuse you of something: this process was not easy, nor fun, nor in any way particularly relaxing. Indeed, my first thought is that I am the poster child of what not to do when attempting to write—if the idea is that leisure itself is for the sake of relaxation and ease, and not the other way around.

To continue with the personal example, the process I go through to write a paper is frankly frightening. Process is not even the right word for it. Procrastination implies too much organization and forethought to be an accurate description of what it takes me to write a paper. Torture . . . torture begins to grasp the tenor of the situation when I attempt to write. Something is tied up; someone refuses to speak; there is threatening and abuse; the results are prolonged; this is what it takes me to put ink on the page. I am the torturer of my own mind, trying to get it to cough up the paper I know it knows how to write, all while the ticking time bomb of a due-date looms large.

Except, I am a lousy torturer, I am terrible at my job, and this causes the whole process to be even more painful. I lie to myself that I thrive off the pressure, like an all-star quarterback down by six points in the fourth quarter executing a two-minute drill to perfection. My wife, on the other hand, tells the truth: I am crazy, delusional, mad. And she is, of course, right. It is madness. I go crazy for a day or two before an article is due. It is no way to live, and it certainly is not nice to pull that sort of thing on anyone you love.

But despite its lack of charm, the situation began to make me wonder, is this not something with which nearly every writer struggles? Are my problems not the problems of most exponents of leisure, bereft of a muse? Yes, we are given a Platonic ideal of the practical draft-after-draft-after-draft, or the occasional person for whom writing is therapy, but I know from my own experience that the scourge of writer’s block is very real and widespread.

So I come back to my wife’s point: maybe writing actually is a sort of madness, a delirium that can come at any time, but just like a child’s fever, it seems to feel most at home during the wee hours of the night. Are not most of us familiar with the experience of burning daylight staring at a blank screen, only to spill the contents of our minds out as through a crack in your skull at some bewitching hour? Is it not the case that most of our words find their way onto the pages of our essays in fits and starts, rather than in a smooth and structured way?

Josef Pieper’s own work, Divine Madness, served as an unexpected source for helping me through this dilemma. Indeed, if one does not believe in actual Muses (something I cannot personally admit), then perhaps you have experienced the glorious joy of a mis-bought book that serves to help you in an entirely different realm of your life, as this book did for me. From its first sentence, Pieper’s work shed light. He points out, “the highest goods come to us in the manner of the mania” (7). Specifically, Pieper is concerned with understanding Socrates’s use of the concept “theia mania” in Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus. But the products of leisure certainly fit into this categories of “highest goods,” and writing chief among them.

Pieper begins his discussion of Plato’s understanding of theia mania by pointing to human nature. “Man” he says, is “indeed of such a kind as to possess his own self in freedom and self-determination” (7). On the other hand, “man, at the same time, is in his personal selfhood integrated into the whole of reality in such a way that he can very well be shaken out of his self-possession” (7). For Pieper, this is not simply a random fact to point out about human nature. There are indeed many ways that someone can be “shaken” out of their regular state of mind. However, Pieper is only interested in this “shaking” when it comes “in such a form that in the very loss of self-possession there is bestowed on him a fulfillment not achieved in any other way” (7-8). For Pieper, the “limitations of man’s nature, as well as its infinite openness and capacity” (18) serve as the background to his exploration of Plato’s concept.

What exactly does this conception of human nature have to do with leisure and troubled writers? First of all, leisure is often cast as the exercise of the self-possessed, of those who already exude a composure and comportment that then allows them, in their near-Stoic tranquility, the ability to think clearly and proclaim it to others. But this does not seem to be what either Plato or Pieper are saying.

To use the example of my writer’s block and tortured composition process introduced above, this “limited but open” aspect to human nature explains the difficulty quite thoroughly. For Pieper, “man is constituted in such a way that . . . he needs to be forced, through inspiration, out of the self-sufficiency of his thinking—through an event, therefore, that lies beyond his disposing power, an event that comes to him only in the form of something unpredictable” (16-17). A too confident image of leisure makes a less experienced practitioner think their unease or difficulty proves they are not capable of leisure, when indeed leisure, if it does anything else at all, provides us the occasion to face this foundational terror at the root of our being, and thus be drawn out of ourselves in some way, compositional work being just one example. But the terror is key!

As Pieper explains, “it is precisely in this loss of rational sovereignty that man gains a wealth, above all, of intuition, light, truth, and insight into reality, all of which would otherwise remain beyond his reach” (17). As it turns out, every writer needs to be inspired, needs a muse to offer them a subject about which they can compose a paper. Part of the madness of composition is the waiting for inspiration; it is not something we can automatically produce by the brute force of our will. But even more so, this inspiration, this “muse” must be something akin to terror, to awe, to wonder, it must be a problem or subject matter that provokes you beyond everyday speech and into the act of composing a rhetorical work, all in the hopes of adequately addressing this problem.

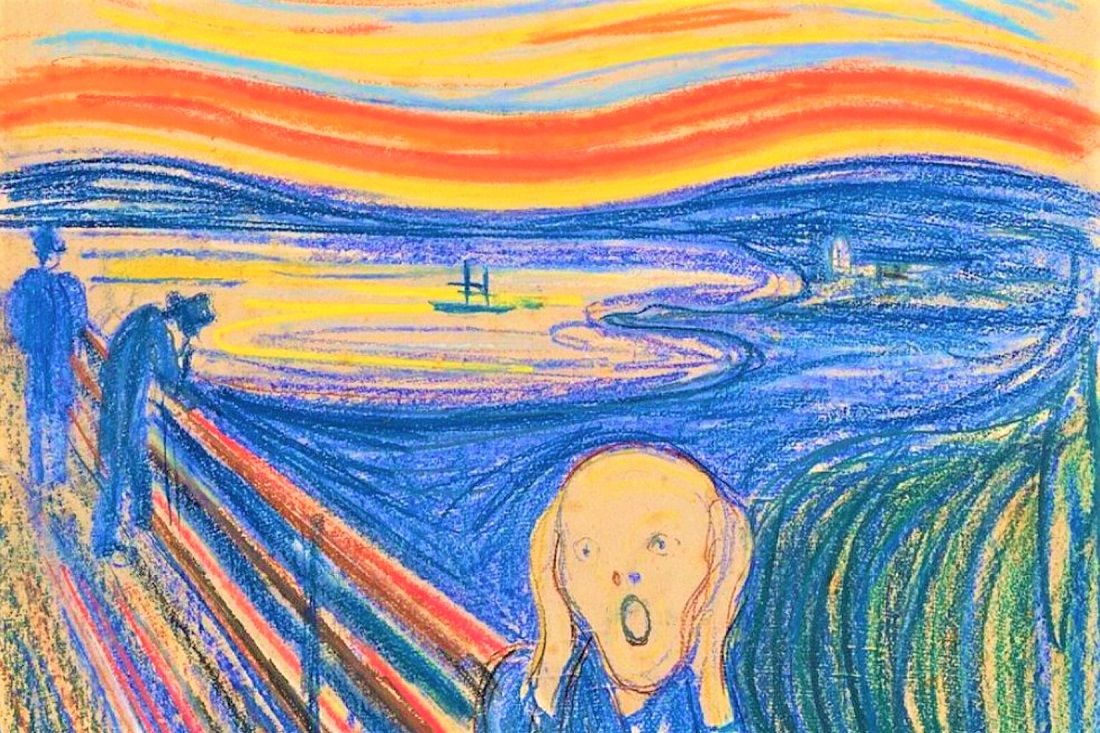

However, this is not even the main benefit Pieper affords us in understanding the terror of leisure. This comes about in his description of madness itself that so interested Plato. It is above all “an event [which] occurs in the form of being-beside-oneself, a theia mania—hence that inspiration likewise appears to ‘the multitude’ as madness” (17). I do not know of a better way to define the fruits of leisure—be they poetry, a written essay, a painting, a song—than a form of “being-beside-oneself.”

Is this not what is so scary about the fruits of leisure, that when the ink bleeds into the physical grain of each page, it somehow has an existence all its own? Is it not the case that every essay I have ever wrote is somehow a part of me, but a part of me that lives outside of me, that has a life of its own? With everyday speech, there is not an analogous sense of fear; if you have a slip of the tongue while talking to your friend, you can quickly say “oops, what I meant to say was…,” and everything usually works out fine. Write something down in an essay, and even if you repudiate every word of it, recant every sentence, the work lives on for whoever wants to read them. And what fruit of leisure is not the same?

Someone can regret something they wrote in the past with all of their heart, but if someone comes upon those words and thinks, “I agree,” there is nothing the author can do to change that fact. If I screw up writing this very article, will it not become something akin to Dr. Frankenstein’s monster? Writing, then, is frightening, is terrifying! Writer’s block, then, is not some deficiency, some lack of self-sufficiency, but a built in defense mechanism, a very understandable fear of what “being-beside-oneself” entails.

However, as much as it is frightening, “being-beside-oneself” is also a fundamental aspect to many of the most important functions in which human beings engage. Pieper makes this clear by considering the most primal aspect of human life that is a “being-beside-oneself,” eros. For Pieper, eros is the most “basic form of man’s being-beside-himself . . . occurring specifically in his encounter with sensual beauty” (42).

Everyone is familiar in some way with the terror and awe of beauty, and many others (John Senior is just one writer who comes to mind) have spoken of this reality much better than I ever could. Suffice it to say, it is easy enough to see that the natural reaction to seeing a beautiful person walking into a room or hearing an engrossing piece of music is not analysis or scrutiny, but awe: a mouth not moving with questions, but a jaw dropping to the floor. It is my contention that something similar happens in the writer’s block that accompanies waiting for the muse.

Of course, while Pieper wants to point to the primal and basic nature of eros in human life, it is not the case that every instance of erotic longing counts as a “being-beside-oneself.” It is not the case that “every infatuation between and Jack and Jill is eo ipso a divine gift (37). Instead, Pieper wants to point out that at its root, “in every erotic emotion there is contained the possibility, the context, and the promise of something reaching infinitely beyond its immediate significance” (37). Stemming again from our nature as human beings, Pieper notes that “beauty, specifically physical beauty, if man approaches it receptively, can affect and strike him more than any other ‘value,’ can push him outside the realm of his familiar and controlled environment” (42). For Pieper, that is precisely why we say of those we find beautiful that they are “attractive.” A man who finds a particular woman attractive is indeed attracted by her, “he is, as we say, ‘moved’ by something else” (43).

Thus, insofar as the act of composition is a “being-beside-oneself” as we established above, it must be an act that is moved by something outside of itself. In other words, the muse must come before we put pen to page because the inspiration attracts us, and not the other way around. Furthermore, any act which is a “being-beside-oneself” relates to the primitive reality of eros. At the very least, it does so by analogy. This must be the case because “nothing evokes this [being-beside-oneself] . . . more intensely than beauty . . . in its power to lead toward a reality beyond the here and now, beyond immediate perception, it cannot be compared to anything in this world” (44). As I said before, the muse must at least be some problem or subject that provokes us to compose. If this is true, then there is at least one basic lesson to take away from all of this and convey to you, that this initial act of composition looks a lot, feels a lot like falling in love.

Now in one regard, this equation between composition and love seems to cause more problems than it solves. How many poems, how many song lyrics could I quote that make this central point: you cannot make someone fall in love with you, and you cannot help with whom you fall in love? In addition, no one who writes their editor and says, “sorry, writing just happens, and the Muse was busy this week” is going to get frequent requests to publish.

However, if composition truly shares this aspect and is something akin to falling in love, there are definitive consequences for the way we approach leisure. If at root, the erotic encounter with beauty undergirds such acts as writing, it will change the way we “do nothing.” It begins with education: teachers are not technicians passing on techniques, but instead are in some way matchmakers “setting up” the students and composition in an encounter that will hopefully get the sparks flying. To teach writing under this model cannot then be a mere didactic imposition of steadfast norms, nor can it be the revolutionary instillation of the newest ideology. By its nature, it is something much more dynamic.

Instead, to teach one leisure is akin to a school of manners, a place out of the imagination of a Jane Austen or a Flannery O’Connor rather than a Harvard or a Duke. The classroom, then, is a place where students come to learn to court a muse! We could imagine grammar and mechanics as something akin to personal hygiene. You might have the most charming personality a potential love interest could ever encounter, but if your hair is matted, your clothes are dirty, and your breath stinks, no one will ever stand close enough to discover your allure. We could also imagine organization and sentence structure as something like learning to interact socially with those you choose to court. You may actually have a winning, thoughtful mind, but if you are rude, discourteous, or awkward, others will quickly ignore all the treasures of your intellect. Of course, being a well-mannered individual does not assure that you will fall in love; however, it is considerably harder to find ones soul mate if you are completely lacking in at least the most rudimentary manners.

Taking this all into consideration, we have not yet considered the most important implication of imagining teaching composition as a school of manners. One-half of the education would indeed focus on what you can do to attract a muse, but the other, perhaps more important, half will involve learning what to look for in a mate. It is the ramifications of this part of the analogy that may have the most far-reaching implications to the classroom. How will beauty move the young if you are never given the chance to encounter it?

But keeping in mind the intention of this essay, these manners are not for their own sake. Neither is the simple act of encountering a Muse. If we are not moved outside ourselves erotically, if we do not come to a “being-outside-ourselves,” then we are as guilty of wasting time as any concerned working class parent may find themselves to be.

Pieper already foresees the danger in such assessments. He points out that “Plato . . . does not hold that beauty moves man’s inner core inevitably and, as it were, automatically, without fail . . . he is very much aware that beauty may well awaken an irreverent, selfish desire” (47). The excitement of desire in and of itself does not guarantee that a desire proper to the “being-beside-oneself” will be attained. This is precisely because there is a difference between “mere desire” and love: “he who desires knows clearly what he wants; at heart he is calculating, entirely self-possessed” (43). Mere desire does not extend beyond the self, and longs for the thing it desires merely as an object, as something to be possessed.

If leisure is creating the space necessary and the manners proper to courting a Muse to terrify us and bring forth something to exist outside of ourselves, the being-beside-oneself of the fruits of leisure, it cannot have grounding in anything so selfish or shallow. The person who loves in such a way as to be beside themselves “does not determine his actions or initiatives all by himself; rather, he is ‘being moved’ when contemplating the beloved” (44).

Plato, then, is not a romantic about this. He is “entirely rational; he has no illusions about the fact that much, if not most, of what generally passes for ‘love’ is nothing but desire” (44). We should not allow ourselves to fall into a sentimentalism that sees any enthusiasm of those who benefit from leisure to pass off as adequate. Our only hope in confronting the terror of being-beside-oneself in the fruits of labor is that they bring us face-to-face with the human and Divine, no matter how alien it seems to your sensibilities: in some ways, the more alien and fearful, the better.

To put eros front and center in a discussion of education presents a real and present danger. As Pieper notes: “In this context, the possibilities of corruption, adulteration, dissimulation, pretension, and pseudo-actualization lie dangerously close” (37). It is this attitude that so riles those on the outside, and provides such ready-made fodder to cast at those who advocate for the importance of leisure. But as I said before, it is the damage that such misdirected leisure can unleash on souls that is truly dangerous. I call this the “onanistic impulse,” a strong characterization, but perhaps not strong enough. It is an impulse that has always existed, although it has seen its stock rise immensely in contemporary times. While the term evokes for us moderns the passions of sexuality, like eros, it is an underlying reality that pervades desires far outside of the sexual.

The onanistic impulse is any desire that does not extend outside of itself, that begins and ends in the immediate context of the individual. Self-gratification and the seeking of pleasure for its own sake are obvious examples of this, but everything, from the desire of leisure for sake of bourgeois class signaling to the myriad of escapist behaviors such leisure provides for the young, all of these desires which do not escape the boundaries of the individual, shares the constitution of this fundamental impulse.

Thus, the instrumentalization of leisure submits to the onanism of the age, and becomes far worse an enemy than those who think “humanities majors cannot get jobs.” This counterfeit of leisure that leads to such onanistic desires provide the very reason to drain the University of non-market dictated departments. It is hard to fight against the tide of STEM and Business school endowments when the proponents of leisure imbibe such a vain imitation of the real leisure.

Eros is not the mere fulfillment of pleasure, especially when we see pleasure as a thing to possess, to horde as a possession. Nothing that is erotic in nature seeks to possess something, but instead enables the person the ability to go outside from him or herself, to allow those things much higher than anything we can possess in a merely instrumental fashion to possess us. Pieper points to Plato, who makes this point by quoting an ancient poem: “For this reason do the gods call Eros not the ‘winged one’ but the ‘wing-giver’” (47). To put it a different way, “by absorbing beauty with the right disposition, we experience, not gratification, satisfaction, and enjoyment but the arousal of an expectation; we are oriented toward something ‘not-yet-here’” (48).

With this “learning-to-wait”, our discussion comes back full circle. What are the terrors of leisure but this: a-being-oriented-toward something outside ourselves, something that we must learn to wait for patiently? Perhaps in the end, what we can learn from all of this not a particular strategy or technique, but the preparation required, the posture necessary to engage in leisure in a fecund manner. This posture is a state which “Plato describes again and again with ever new expressions: a desire to soar on wings while being utterly unable to do so; being beside oneself while not knowing what is going on; ferment, restlessness, helplessness” (43).

If leisure turns out to be painful, we should rest content in the fact that no one less than Socrates compares love, compares eros to “the uncomfortable condition of a child who is teething” (43). This run-in with beauty is not something we control or handle in any self-sufficient way; a person who encounters beauty “has to ‘suffer’ all this” (43). Yet through this suffering, the sufferer stands to gain so much.