The life of Catholic novelist, philosopher, and essayist Walker Percy was shaped, in part, by an uneasy confrontation between Stoicism and Christianity.[1] Although Percy was raised in a noble, affluent, and prominent Southern family, his background was also marked by a family history of melancholy, depression, tragedy, and suicide.[2] As Paul Elie explains, “There was a suicide in nearly every generation. One Percy man dosed himself with laudanum; another leaped into a creek with a sugar kettle tied around his neck. John Walker Percy—Walker Percy’s grandfather—went up to the attic in 1917 and shot himself in the head.”[3] His father, Leroy Pratt Percy, committed suicide in the attic in 1929. Percy remarked, “The central mystery of my life is to figure out why my father committed suicide.” In fact, wondering if he were destined for the same fate, he often referred to himself as an “ex-suicide.”[4] Not long after the death of his father, Percy lost his mother in a tragic car accident. Committed Stoic, William Alexander Percy, Walker’s second cousin, adopted all three Percy boys.

Stoicism and the American Landscape

At the heart of Stoicism lies an acute awareness of the tragic situation of the human person fundamentally conditioned by fate. A basic opposition exists between that which does not depend on us (external causes, fate, indifference) and that which does depend on us (the will to do good and act in conformity with reason). For the Stoic, unhappiness pervades human life because we seek to obtain the things we cannot obtain and avoid the evils that are inevitable and inescapable. The latter—the will to do good that depends on us—is an “unbreachable fortress which everyone can construct within themselves.” It is the locus of “freedom, independence, invulnerability, and that eminently Stoic value, coherence with ourselves.”[5]

Stoicism is an enduring part of the American landscape. Thomas Jefferson credits Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Epictetus with offering ideals that became part of “the higher thought of Western civilization: nobility of character, high ethical purpose, the ideal of self-sacrifice, belief in God and His divine providence, emphasis on virtue as the highest good and on action to make it effective, the need of bringing conduct into conformity with the law of Nature, and the realization of a high and stern sense of duty in public and private life.”[6] Jefferson adds Jesus of Nazareth to the mix, though he had to abstract the “real” Jesus from the ecclesiastical “rubbish” in which he was mired. One must dig up this “most sublime morality” from the pious trappings of the Gospel writers as if separating “the diamond from the dunghill.”[7] As Jefferson envisioned, “Epictetus and Epicurus give laws for governing ourselves, Jesus a supplement of the duties and charities we owe to others.” This pagan-Jesus balance honored both the individual self and our obligations to the other.

There is also a detectable strain of Stoicism in American literature. Think of Ralph Waldo Emerson and his younger friend, Henry David Thoreau, the so-called “stoic of the woods” who vowed “to live so sturdily, and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.”[8] Such Stoicism is embodied as well in Hemingway’s Santiago of Old Man and the Sea, who finds the strength to be self-reliant in the face of the all-pervasive threats of nature (14). I need only mention as well the lawyer, Atticus Finch, of To Kill a Mockingbird, and coach Eric Taylor of Friday Night Lights: “Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Can’t Lose”—the code of the warrior, the Stoic man of classical virtue—family, hometown roots, gritty virtue and God.[9] As Seneca writes, “No school has more goodness and gentleness; none has more love for mankind or is more devoted to the common good. The goal it assigns for us is to be useful, to help others, and to take care not only of ourselves but of everyone in general and of each person in particular” (135).

A certain kind of new Stoicism has emerged in contemporary culture in the cross-pressure that Charles Taylor has called the “nova effect.” Life-hack Tim Ferriss, whose podcast “The Tim Ferriss Show” was the first to surpass 100 million downloads, regularly advocates for the integration of Seneca into one’s daily practice, as does the popular work of Ryan Holiday. Their respective projects are just two among an explosion of different options—third ways, if you will—for discovering meaning in our secular age.[10]

How ought one parse out the relationship between these two systems of thought and modes of life? This is an existentially relevant question for many modern wayfarers, myself included; I am a regular, albeit critical, listener of Tim Ferriss, and more than a recreational reader of Seneca. The Christian tradition has, of course, reckoned with this question in a robust way and scholars of early Christianity have offered a multitude of way to navigate this tension.[11] I am somewhat persuaded by these attempts at a happy synthesis. But, in this essay, I want to consider them in a more dialectical vein—as “traditions in conflict.”

Stoic and Christian Visions as Rival Traditions

In his book One True Life, C. Kavin Rowe argues that a serious conversation about the relation of Stoicism to Christianity requires us to consider them as “rival traditions of life.”[12] What both the Roman Stoics and the early Christians shared is the claim that “their pattern of life was the truth of all things but also that such truth could be known only through the time it took to live the tradition that was the truth.” The truth of things was communicated through practices of discipline, instruction, formation, apprenticeship, care, and healing. It was not a matter of the privileged and detached cosmopolitan eclectically constructing insights on the human condition, the passions, or, for example, the meaning of pneuma. Rather, truth was worked out in the midst of contested ways of life. Rowe writes, “No amount of overlap in the treatment of, say, wrath or anger, no amount of agreement about the necessity of breaking with daily (pagan) life, no amount of commonality in condemnation of wayward living can erase or even blunt the fact that Stoicism and Christianity stand face to face as competing traditions of true lives” (6).

In illuminating Stoicism and Christianity as rival traditions, Rowe draws upon Alasdair MacIntyre’s understanding of “tradition” as explained in Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry. For MacIntyre, tradition is not another rendition of pure reason at work, but is more like a craft. The practitioners of a craft self-consciously relate to its history, engage in its debates, and aim toward its future development. The art of rationality requires more than sharpening one’s mind; it requires an ongoing, holistic transformation of the person—to become the kind of person that can embrace the truth (183). A tradition of inquiry is best nurtured in a master/apprentice relationship; a cooperative activity that enables one to develop the habits required to become a competent member of the craft. Unlike the Enlightenment cosmopolitan and the postmodern genealogist, this thick understanding of tradition implies a particular intellectual and moral community, illustrated, for example, through the lives of Socrates and Aquinas. Traditioned inquiry is then primarily located, not in professionalized academic departments, but in religious communities where “theological reflection presupposes the moral habituation needed to read texts with rational competence” (184). In sum, a tradition of inquiry is a “morally grained, historically situated rationality, a way of asking and answering questions that is inescapably tied to the inculcation of habits in the life of the knower and to the community that originates and stewards the craft of inquiry through time.” Christianity and Stoicism are best described as traditions in this robust sense of the term (184).

Rowe contrasts the “traditioned rationality” and habits of life of Paul, Luke, and Justin Martyr with that of Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius. He contrasts their visions of God and world, the human being, Jesus of Nazareth, death, politics, and society. The assumption of much comparative work (to Rowe’s consternation) is that the two traditions share “fundamentally the same, similar, or at least commensurable commitments” to “some sort of reality called God or the Divine, or to a particular doctrine called Providence, or to a goal called Human Betterment, or to certain common aspects of human experience called the Passions or the Virtues, and so on” (224). The problem with this assumption is that the two narratives conflict fundamentally in their substantive visions of reality. Take, for example, their respective accounts of human death: to attempt to translate a Christian understanding of death within stoic terms requires the transposition of the use of sin, enemy, soul, resurrection of the body, judgment and so on “into a pattern that says death is natural, part of the cycle of the whole, not to be feared by rationally directed persons, incapable of being overcome, preferable to weakness even if it means suicide, and so forth” (232). The example of death illustrates that these two traditions “stand irresolvably” in existential and narrative rivalry (237). I turn to this tension in the life and writing of Percy.

Walker Percy’s Quest

Early in his life Percy had an inclination toward science. As Jay Tolson observes, even in his high school years in Greeneville, Mississippi in the wake of deep tragedy, Percy was “looking for certainties, and though he attended Greenville’s Presbyterian church along with his brothers,” he found them, not in religion or in his Uncle Will’s Stoicism, but “in science—or, more accurately, in that exaggerated faith in science that is called scientism.”[13] Attracted by its elegance, beauty, and simplicity, science exhibited for him a “constant movement” in the “direction of ordering the endless variety and the seeming haphazardness of ordinary life by discovering underlying principles.”[14] Trained at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, Percy contracted pulmonary tuberculosis while working as a pathologist at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. As a result of this diagnosis, he was forced to spend a significant amount of time in a sanatorium in the Adirondack Mountains. This forced exile deeply transformed his inner life, and indeed, shaped the intellectual and existential trajectory of the rest of his life.

What were the consequences of this misfortune and interruption? Although Percy never abandoned his allegiance to and a love for the “rigor and discipline of the scientific method,” he experienced “a shift of ground, a broadening of perspective, a change of focus.”[15] On his sick bed, he began to read Dostoevsky, Camus, Jaspers, Marcel, Heidegger, among others. Indicative of his expanding horizons, Percy became less interested in the physiological and pathological processes of the human body and more fascinated by questions concerning the nature and destiny of human persons, and more specifically, by the peculiar predicament of human persons “thrown” into a modern technological society. Percy writes:

If the first great intellectual discovery of my life was the beauty of the scientific method, surely the second was the discovery of the singular predicament of man in the very world which has been transformed by science. An extraordinary paradox became clear: that the more science progressed, and even as it benefitted man, the less it said about what it was like to be a man living in the world. Every advance in science seemed to take us further from the concrete here-and-now in which we live.[16]

This paradox illuminates what Percy considered a gaping hole in a reductionist scientific worldview: that however beautiful and legitimate in its own right, it failed to fully account for the very human being doing the science. Percy recounts that after many years of scientific education he “felt somewhat like the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard when he finished reading Hegel. Hegel, said Kierkegaard, explained everything under the sun, except one small detail: what it means to be a man living in the world who must die.”[17] In fact, as Percy later observes in Lost in the Cosmos (1983), our advances in “an objective understanding in the Cosmos,” in reality, distances the self “from the Cosmos precisely in the degree of the advance—so that in the end the self becomes a space-bound ghost which roams the very Cosmos it understands perfectly.”[18] After his stay in the sanitarium and in the wake of these shifting horizons, Percy left medical practice and pursued a career as a writer.

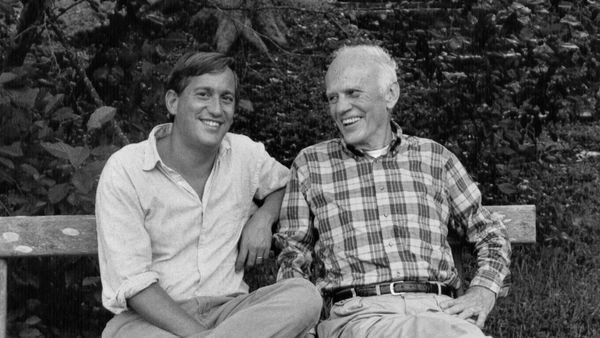

William Alexander Percy—“Uncle Will” as the Percy boys called him, along with their friend Shelby Foote—proved to be the great formative influence in his life, nurturing a love of books and music that would have an enduring impact. If not for Will, Percy speculated that he would have ended up a car salesman in Athens, Georgia. Uncle Will’s house was perhaps the most interesting house in Mississippi. It was a respite for poets, novelists, and musicians visiting the region.

Will Percy deliberated over the daunting task of directing the younger generation “toward the good life” as he reflects in his memoir Lanterns on the Levee.[19] Recognizing that the old Southern way of life no longer existed, he had “no desire to send these youngsters” into “life as defenseless as if they wore knights’ armor and had memorized the code of chivalry.”[20] With sadness in his eyes and aware of the limitations of his own Stoic vision, Uncle Will sent the boys to the churches for the kind of community and wisdom they had to offer. As Kieran Quinlan notes, “When William Alexander Percy abandoned Catholicism, he was left with that old staple of Southern aristocrats, the teachings of Marcus Aurelius tempered by a commitment to a purely ethical Christianity. But he does not appear to have been so absolutely assured of his own choice that he was willing to impose it on others.”[21] As Will mused, “our concern is here, and with the day so overcast and short, there’s quite enough to do.”[22] “So I counsel the poor children,” Will adds. “But I long for the seer or saint who sees what I surmise—and he will come, even if he must walk through the ruins.”[23]

Part of Will’s response to these young boys—in the midst of his “own darkness”—placed in their hands two texts: the Gospels and the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Even though the Gospel texts were full of contradictions, Will still believed they shed “more light than darkness on the heart-shaking story they tell.”[24] In the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, we discover the wisdom that we “need be less than tight-lipped, courteous, and proud, though all is pain.”[25] Despite Will’s accomplishments, social capital, and worldly travel, Walker described, with his enviable knack for observation, a certain kind of beautiful sadness in Will’s eyes.

Percy on Stoicism and Christianity in the South as Rival Traditions: The Issue of Race

Walker Percy of course did not ultimately embrace (fully, at least) Uncle Will’s blend of Stoicism, ethical Christianity, and eclectic mysticism. The challenges posed by his Southern, aristocratic roots would come to the fore in the 1950’s. Although he was not naturally a political animal, his interest in civil rights and social justice grew in this decade. He had always been compassionate and aware of the plight African Americans. Still, as Jay Tolson notes, not unlike most “white southerners of his class, he had believed that segregation was a necessary part of the southern way of life.” Reconstruction, after all, offered proof that legal and political solutions were inadequate. The racial problem, so he thought, was rooted in people’s hearts and would have to change slowly over time (250). He would begin to reconsider this presupposition in the early 1950’s. Perhaps the Southern Stoicism of Uncle Will carried dangers and prejudices not fully seen before. The influence of Shelby Foote can be detected in this realization, but even as Foote admitted, Percy’s Catholic faith played a more decisive role. As a convert, Percy took seriously the social message of the Gospels; he was aware of the mission of Dorothy Day, Fr. Louis Twomey, and Fr. Fichter at Loyola New Orleans, who produced a newspaper called “Christian Conscience.”[26] Although he would never become an activist in the strictest sense, “the words and actions of committed Catholic reformers forced him to question and revise his older assumptions about what needed to be done.” Add to this, the ruling on Brown v. Board of Education, the school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, and his own brother Roy’s fight for civil rights in Greenville, Mississippi, Percy realized that the “old mixture of paternalism and well-intentioned gradualism was not enough.”[27]

Percy expressed his outrage in a Commonweal article entitled “Stoicism in the South.”[28] He began the article with an admission: “It is always hard to generalize about the South, harder perhaps for the Southerner, for whom the subject is living men, himself among them, than for the Northerner who, in proportion to his detachment, can the more easily deal with ideas” (83). He also expressed a dose of humility: “no white Southerner can write a j’accuse without making a mea culpa; no more is the average Northerner, either by the accident of his historical position or by his present performance, entitled to a feeling of moral superiority” (84).

One of the realities that Percy brings to light is that the South always had “a stronger Greek flavour than it ever had a Christian. Its nobility and graciousness was the nobility and graciousness of the Old Stoa.” He highlights the words of Marcus Aurelius as capturing the best of the South: “Every moment think steadily, as a Roman and a man, to do what thou hast in hand with perfect and simple dignity, and a feeling of affection, and freedom, and justice.” In relation to this tradition of Stoic virtues, the Beatitudes and the doctrine of the Mystical Body” sound rather foreign to Southern ears. “The South’s virtues,” Percy writes, “were the broadsword virtues of the clan, as were her vices, too—the hubris of noblesse gone arrogant.” As for the Christian layer, the “Southern gentleman did live in a Christian edifice, but he lived there in the strange fashion Chesterton spoke of, that of a man who will neither go inside nor put it entirely behind him but stands forever grumbling on the porch” (84). His allegiance was more to Pericles, Hector, and Marcus Aurelius, and less to Abraham and Paul: “When he named a city Corinth, he did not mean Paul’s community. How like him to go into Chancellorsville or the Argonne with Epictetus in his pocket; how unlike him to have had the Psalms” (85).

The Stoic way best suited to the agrarian landscape of the 19th century South. It was based on a particular hierarchical structure that could and did not survive. What survived was a “poetic pessimism” and “social decay” that privileged the “wintry kingdom of the self”—creating the conditions for different forms of human alienation and the vagaries of consumerism (85). The Stoic response in such a situation is “to sit tight-lipped and ironic while the world comes crashing down around him” (86). This response, as Percy submits, is a far cry from a Christian response; hence we have two rival traditions at work:

It must be otherwise with the Christian. The urban plebs is not the mass which is to be abandoned to its own barbaric devices, but the lump to be leavened. The Christian is optimistic precisely where the Stoic is pessimistic. What the Stoic sees as the insolence of his former charge—and this is what he can’t tolerate, the Negro’s demanding his rights instead of being thankful for his squire’s generosity—is in the Christian scheme the sacred right which must be accorded the individual, whether deemed insolent or not. For it was not the individual, after all, who was intrinsically precious in the Stoic view—rather, it was one’s own attitude toward him, and this could not fail to specified by the other’s good manners or lack of them. If he became insolent, very well: let him taste the bitter fruits of his insolence. The Stoic has no use for the clamoring minority; the Christian must have every use for it (86).

This dynamic of rival traditions was revealed in the way many of Percy’s fellow Catholics responded to the then Archbishop of New Orleans Joseph Rummel’s pastoral letter declaring that segregation was sinful. Rummel was subjected to “the old Klan treatment” (a burning cross in his yard) and plenty of complaints from his Catholic faithful. Just days before Good Friday, a notice appeared in the New Orleans Times-Picayune inviting “Roman Catholics of the Caucasian Race” to join an “Association of Catholic Laymen” for the purpose of “investigating and studying the problems of compulsory integration; to seek out, make known and denounce Communist infiltration, if there be any, in the integration movement” (87). Percy referred to this statement unequivocally as a “tragic distortion” of the word Catholic. “Here again,” Percy lamented, “the upper-class white Catholic has not distinguished himself.” They can no longer afford the luxury of Creole Catholicism—“going to daily Mass at the Cathedral on a segregated streetcar and seeing God’s will in it” (87).

The Stoic-Christian Southerner is offended when the Archbishop of New Orleans calls segregation sinful (or discusses the rights of labor). He cannot help feeling that religion is overstepping its allotted area of morality. In the comfortable modus vivendi of the past, he had been willing enough to allow Christianity a certain say-so on the subject of sin—by which he understood misbehaviour in sexual matters, or in drinking and gambling. He is therefore confused and obscurely outraged when Christian teaching is applied to social questions. It is as if gentleman’s agreements had been broken. He does not want the argument on these grounds, but prefers to talk about a “way of life,” “states’ rights,” and legal precedents, or to murmur about Communism, left-wing elements, and infiltration (87).

Yet the Stoic-Christian, Percy challenged in this essay, must also reckon with his own Christian heritage and answer Archbishop Rummel’s pastoral challenge. And the good old Stoic answer, Percy provocatively stated, was “no longer good enough for the South” (88).

Percy’s reckoning with the rival traditions of Stoicism and Christianity did not end in the mid 1950’s; it was a tension that surfaced sometimes in significant ways in his works of fiction. His National Book Award winning novel, The Moviegoer, just to take one example, portrays the protagonist Binx Bolling’s rejection of his influential Aunt Emily’s brand of Stoicism.[29] In a letter to Binx, Aunt Emily paraphrased the words of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus: to think at every moment “as a Roman and a man, to do what thou hast in hand with perfect and simply dignity, and a feeling of affection and freedom and justice” (78). Aunt Emily exhorted Binx to live a life of simply duty, to go to medical school, and to usefully serve humanity. She argued, in good Stoic fashion, that a “man must live by his lights and do what little he can and do it as best he can.” Although in this world “goodness is destined to be defeated,”—notice the tragic view—a man “must go down fighting”—a habit of mind that constitutes its own kind of victory (54). At the end of the novel, Aunt Emily, in her speech of abandonment to Binx, expresses dismay at his failure to fully embrace the “natural piety” of Stoicism on which he was raised. Binx’s love for Kate, in all her brokenness—drug use, suicidal tendencies, and paralyzing fear—violated Aunt Emily’s high hopes.

After Aunt Emily’s speech, Binx sits with Kate in her 1951 Plymouth outside a church on Ash Wednesday, expressing in conversation a merciful and loving embrace of the vulnerable Kate. The novel ends with Binx looking in his rearview mirror at an African American departing the church. Here he expresses an openness to the mediation of God through mundane ashes, a openness surrounded with mystery and ambiguity:

It is impossible to say why he is here. Is it part and parcel of the complex business of coming up in the world? Or is it because he believes that God himself is present here at the corner of Elysian Fields and Bons Enfants? Or is he here for both reasons: through some dim dazzling trick of grace, coming for the one and receiving the other as God’s own importunate bonus? It is impossible to say (235).

Whereas Aunt Emily’s tragic Stoicism—despite its noble intentions—nurtured a rejection of outcasts and an embrace of the defeat of goodness, Binx’s openness to the religious meaning of the ashes, which symbolize death and the salvific mystery of the cross, indicates the possibility of religious hope.

Conclusion

Nodding to the fabric of Stoicism that runs deep in American culture, this essay asked how one ought to navigate the relationship between these two systems of thought and modes of life. Rowe challenged us not to fall too easily into an easy blending of ideas and practices in the manner of a cosmopolitan modernity. A further question remains for me: How might such an integration look when grounded in an “authentic cosmopolitanism” or in global communitarian networks committed to cognitional, volitional, and existential authenticity? But this further question will have to wait. My limited claim is that we cannot ignore understanding these life-visions as robust rival traditions in MacIntyre’s sense of the term. They emerged historically as “ways of life”—as lived traditions of formation, practice, thinking, healing that stand in so many ways in existential and narrative rivalry. This existential and narrative rivalry came to life in the example of Walker Percy. Percy never renounced Stoicism tout court; in fact, he often defended its virtues. Still, it was not enough and did not offer him the resources for navigating the pressing questions and dilemmas that arose in his own life (and his region). Stoicism, after all, could not adequately resist his longstanding family heritage of melancholy, depression, and suicide. Nor could it rid him of the patriarchal and hierarchical deficiencies of slavery and racism in the South. The rivalry of traditions was captured in his community’s resistance to Brown v. Board of Education, in his literary dichotomy between Binx Bolling and Aunt Emily, and in his depiction of the Southern gentleman who lived surrounded by a Christian edifice, but who would not go inside. He was content, as Percy noted, to stand forever grumbling on the porch.

[1] I draw in this section from my other writings on Percy. See the following: Randall S. Rosenberg, “Guarding a Metaphysics of the Whole Person: Walker Percy and Bernard Lonergan,” Gregorianum 95.3 (2014): 577-596; “The Human Quest and Divine Disclosure according to Walker Percy: An Examination in light of Lonergan,” Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture (January 2014); “Text-Based Friendships and the Quest for Transcendence in a Global-Consumerist Age,” Grace and Friendship: Theological Essays in Honor of Fred Lawrence, eds. M. Shawn Copeland and Jeremy Wilkins (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2016): 213-35; and “The Retrieval of Religious Intellectuality: Walker Percy in Light of Michael Buckley,” Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature (Spring 2011).

[2] For an account of the Percy family, see Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy, and Imagination in a Southern Family (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

[3] Paul Elie, The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 10.

[4] Grant Kaplan, “Diagnosing Modernity: Eric Voegelin’s Impact on the Worldview of Walker Percy,” Religion and the Arts 15 (2011), 341.

[5] Pierre Hadot, What is Ancient Philosophy? (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2004), 127.

[6] Lewis Lawson, “The Moviegoer and the Stoic Heritage,” Following Percy: Essays on Walter Percy's Work (Albany: Whitston, 1988), 66.

[7] Lawson, “The Moviegoer and the Stoic Heritage,” 67.

[8] See Stoic Strain in American Literature: Essays in Honour of Marston LaFrance, 1927-75, ed. D.J. MacMillan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979), 6-7, 14.

[9] Peter Augustine Lawler, American Heresies and Higher Education (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2016), 204-5.

[10] Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap), 302.

[11] See Sarah Catherine Byers, Perception, Sensibility, and Moral Motivation in Augustine: a Stoic-platonic Synthesis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[12] C. Kavin Rowe, One True Life: the Stoics and Early Christians as Rival Traditions (New Haven: Yale, 2016).

[13] Jay Tolson, Pilgrim in the Ruins: A Life of Walker Percy (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 96.

[14] Percy, “From Facts to Fiction,” Signposts in a Strange Land, ed. Patrick Samway (New York: The Noonday Press, 1991), 187.

[15] Percy, “From Facts to Fiction,” Signposts in a Strange Land, 188.

[16] Percy, “From Facts to Fiction,” Signposts in a Strange Land, 188.

[17] Percy, “From Facts to Fiction,” Signposts in a Strange Land, 188.

[18] Percy, Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (New York: The Noonday Press, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1983), 12-13.

[19] William Alexander Percy, Lanterns on the Levee (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1941).

[20] Percy, Lanterns on the Levee, 312.

[21] Kieran Quinlan, Walker Percy: The Last Catholic Novelist (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 23.

[22] Percy, Lanterns on the Levee, 321.

[23] Percy, Lanterns on the Levee, 321.

[24] Percy, Lanterns on the Levee, 316.

[25] Percy, Lanterns on the Levee, 316.

[26] Tolson, Pilgrim in the Ruins, 254.

[27] Tolson, Pilgrim in the Ruins, 252.

[28] Percy, “Stoicism in the South,” in Signposts in a Strange Land. Subsequent references to this essay will be cited in parentheses.

[29] Percy, The Moviegoer. New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1961.