But when you pray, go to your inner room, close the door, and pray to your Father in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will repay you.

—Matthew 6:6Whatever path you choose to follow, you will never find the limits of the soul, for its depths are most great.

—Heraclitus Fragment

In a well-known passage from his 1971 essay on Christian living, Karl Rahner writes that “the devout Christian of the future will either be a ‘mystic,’ one who has experienced ‘something,’ or he will cease to be anything at all.”[1] If phenomenology is truly the most precise science of lived experience, would it not be appropriate to conduct a phenomenology of mysticism—more broadly, a phenomenology of prayer—in order to promote the mystical life? Answering this question in the affirmative, I will attempt to do three things:

- introduce the method of phenomenology for beginners,

- assess the status of phenomenology within Catholicism today, and

- suggest some preliminary steps toward a phenomenology of Christian prayer, with reference to the life and work of Gerda Walther (1897–1977).

What Is Phenomenology?

Phenomenology is a philosophical method inaugurated by twentieth-century German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). In formulating this new method of philosophical investigation, Husserl sought to rescue the self-evidential objectivity of “things themselves” (Sachen selbst) from the vague subjectivity of psychological relativism, even if masquerading as empirical probabilism.[2] Husserl claims that phenomenology involves a “cognition which can bring to absolute self-givenness not only particulars, but also universals, universal objects, and universal states of affairs.”[3] In other words, phenomenology, as the “science of absolute honesty,” grants us pure access to truth as it gives itself through conscious intuition.[4]

Phenomenology awakens a person to the true givenness (Gegebenheit) of phenomena that floods perception. According to Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “the whole effort of phenomenology is to recover this naïve contact with the world and to give it, at last, a philosophical status.”[5] It is the child who paradoxically serves as the pinnacle phenomenologist and teaches the adult how to approach the world with contemplative wonder once again. I would suggest that there are three basic steps to the method of phenomenology:

- Bracket the natural attitude

- Receive and contemplate what gives itself in experience

- Interpret and describe what gives itself in experience[6]

To bracket the natural attitude, I must unmask the natural attitude operative in myself. The natural attitude refers to all those presuppositions, assumptions, and biases about “what is.” By intentionally bracketing the natural attitude, I become perceptually open and docile to “what gives.” Second, once I have begun to bracket the natural attitude, I receive all the phenomena that give themselves within my lived experience, patiently contemplating how they give themselves by themselves. My active intentionality of bracketing the natural attitude gives way to a passive intuition of receptivity to all that gives itself to me. Third, I must interpret all the phenomena that give themselves to me by describing how they give themselves. Through the process of interpreting and describing the givenness of phenomena, I can communicate my lived experience to other people, testifying to the “things themselves” with an observant attentiveness to meaning. Ultimately, phenomenology describes the meanings or essences of phenomena (the “things themselves”) that give themselves within lived experience.[7]

Phenomenology and Catholicism Today

In his 2003 Address to a Delegation of the World Institute of Phenomenology of Hanover, Pope Saint John Paul II summarized well the method of phenomenology in relation to Catholicism:

Phenomenology is primarily a style of thought, a relationship of the mind with reality whose essential and constitutive features it aims to grasp, avoiding prejudice and schematisms. I mean that it is, as it were, an attitude of intellectual charity to the human being and the world, and for the believer, to God, the beginning and end of all things. To overcome the crisis of meaning which is characteristic of some sectors of modern thought, I insisted, in the encyclical Fides et ratio (cf. n. 83), on an openness to metaphysics, and phenomenology can make a significant contribution to this openness.[8]

There are two main points to note from these words concerning phenomenology within a Catholic perspective:

- phenomenology cultivates an essentially positive attitude of intellectual charity to the other, the world, and God, and

- phenomenology by itself cannot constitute the fullness of Catholic philosophy because the foundation of Catholic philosophy—that is philosophia perennis (“perennial philosophy”)—always was and always will remain classical metaphysics.[9]

Elsewhere, in his 1953 habilitation thesis Evaluation of the Possibility of Constructing a Christian Ethics on the Assumptions of Max Scheler’s System of Philosophy, John Paul II (Karol Wojtyła) wrote that the theologian “should not forego the great advantages which the phenomenological method offers his work,” and yet, at the same time, “the Christian thinker, especially the theologian, who makes use of phenomenological experience in his work, cannot be a Phenomenologist.”[10] What does John Paul II (Wojtyła) mean by these paradoxical remarks? He means that phenomenology by itself lacks an epistemological anchor to the truth of being and existence that metaphysics supplies. Because phenomenology brackets the question of “what is,” it cannot furnish an ethical basis of judgment as to “what ought to be done.” In this respect, phenomenology is all sail and no anchor, but at this point in the history of Western philosophy, metaphysics is all anchor and no sail. Catholic thought today stands in need of both anchor and sail.

John Paul II and many other notable Catholic thinkers of the twentieth century, including Dietrich von Hildebrand, Edith Stein, Gabriel Marcel, Karl Rahner, Erich Przywara, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Robert Sokolowski, coupled phenomenology and metapysics in order to decouple meaning and its absence. While taking seriously the repudiations of the First Vatican Council and Popes Pius X, Benedict XV, Pius XI, and Pius XII against the errors of Modernism (including agnosticism, rationalism, and vital immanence), we must not confuse or conflate phenomenology with “phenomenalism.”[11] Phenomenalism is an epistemological theory that claims we can know only phenomena as mere appearances without having direct access to the things themselves.

For Husserl, in contrast, there is an essential unity between what I experience (the “phenomenon”) and the thing in itself (the “noumenon”). This is to say that what I experience is the thing in itself, thereby surmounting the Kantian dualist segregation of the noumenon from the phenomenon within conscious perception.[12] Nevertheless, phenomenology today risks slipping into Modernist tendencies if it evacuates its dialectical pairing with metaphysics, and, even more fatal, if it neglects altogether the data of divine revelation.

In most cases, it seems that phenomenology (and philosophy in general) proceeds according to the tacit doctrines of methodological atheism, materialism, rationalism, religious indifference, and anthropocentrism.[13] Fortunately, a “theological turn” within phenomenology has been observed over the course of the twentieth century, but Catholic philosophy still struggles with its primary point of departure. Why must philosophy always begin and end with man when its source and summit is God? After all, the incarnation of God comes from God and returns to God. What we need today is a Christocentric philosophy—a Christocentric phenomenology—that begins with the revelation of Christ and aims at consummation in Christ. Phenomenologically speaking, an intentionality of faith must commence and sustain the enterprise of phenomenological investigation. Unless we believe, we will not understand (Saint Augustine). Just as “a body without a spirit is dead” and “faith without works is dead” (James 2:26), philosophy without theology is dead. Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation of the death of God and Martin Heidegger’s central atheistic notion of “being-toward-death” say as much. Instead, what phenomenology needs today is the inverted concept of “being-toward-resurrection,” beginning with the resurrected Christ and ending with the resurrected Christ. For where thought begins is where it will end; where the archer assigns the target, the shot is sure to follow. Might phenomenology ascend to its most authentic status by allowing itself to be transfigured into a Christocentric phenomenology of prayer?

Toward a Phenomenology of Prayer

For Catholic philosophy that incorporates the method of phenomenology as part of a greater whole, a phenomenology of prayer should begin with just that, prayer. “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.” Prayer begins with the data of God’s self-revelation, and the joys and sorrows of the human heart follow. By insisting on a Christocentric starting point, rather than a theocentric or an anthropocentric one, the phenomenological aperture is calibrated appropriately and accurately to proceed with an obedient hermeneutics to what gives itself within the lived experience of Christian prayer. Even before a confession of sin and praise can be uttered (Saint Augustine), God gives. Yes, God gives as the Absolute, as conscience, as the horizon of givenness, as possibility par excellence, but even more, God gives liturgically and sacramentally as Eucharistic Presence.

The lifeworld (Lebenswelt) of givenness gives itself with implicit and explicit reference to the paradigmatic Given: “This is my body given up for you.” Even for givenness, “the paradigmatic is the real.”[14] From where else would the meaning of the concept of givenness come, if not from the one who gives himself up—who traditions himself (paradídomi)—to the point of abandonment? Forgiveness is made possible by the sacramental givenness of the Given who gives himself up perpetually as the very condition of the possibility of possibility. The network of givenness we call the universe orbits around the Given who gives himself up without chance or delay.

The second question—beyond that inquiring into the “first comer” (le premier venu) of prayer—concerns the vocative creaturely participant of prayer. Who is the one addressed by God? The answer is not homogeneous. The addressee could be an adult or a child. The addressee could have impairments and disabilities of various kinds. The addressee could be undergoing a serious illness. The addressee could be from a variety of races, ethnicities, cultures, and historical eras. The addressee could be oppressed or carefree, addicted or liberated, loved or forgotten. The addressee could be at prayer alone or in community. Let us not presume, therefore, that the one God addresses in prayer is circumscribed within a completely common genus.

From the standpoint of age, the child may very well be the most interesting addressee to observe in prayer. And when we pray as adults, is there not always something of the child—something of our own personal childhood—renewed and resurrected within us? If we pray to our heavenly Father, does this not imply a filial status that was granted us through adoption (see Romans 8:15; Galatians 4:5–6)? As long as we recognize and receive this revealed filial status as the vital nexus of relating to God, we may proceed toward a Christocentric phenomenological prolegomenon to prayer.[15]

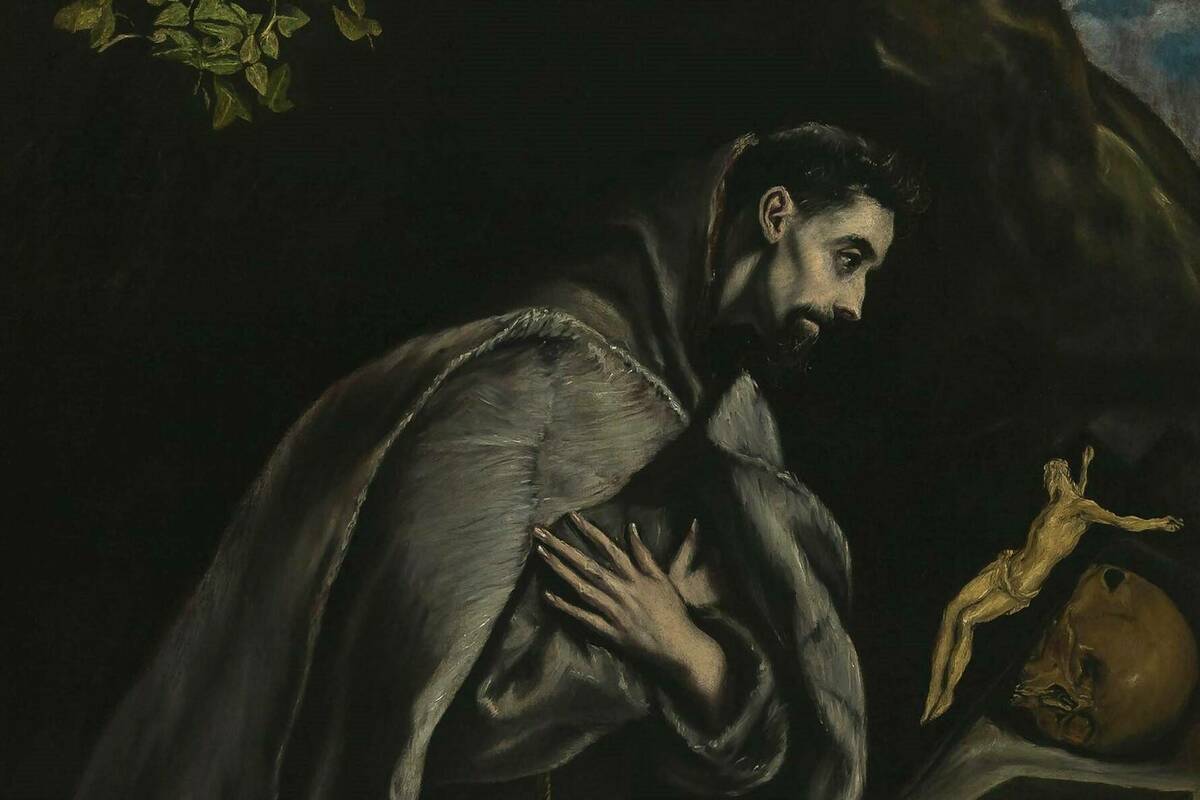

One of the more interesting and relevant voices for guiding us along this uncharted territory is the twentieth-century German philosopher Gerda Walther (1897–1977). Though only the first section of her most important full-length work on the phenomenology of mystical experience, Phänomenologie der Mystik (1923), has been translated into English, this book, with reference to the spiritual testimonies of Saint Teresa of Ávila and the contemplative poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, serves as a significant point of reference for developing a phenomenological analysis of Christian prayer and mysticism.[16] Raised in a thick milieu of atheistic Marxism and socialism, Walther would experience a surprising conversion to Catholicism later in life. Leading up to her conversion were her studies in phenomenology at the feet of Edith Stein, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Alexander Pfänder, as well as her friendships with Roman Ingarden and Hedwig Conrad-Martius.

She was fascinated by the phenomenality of community (Gemeinschaft) and a rational exploration of paranormal experiences, especially those within the religious domain. Her peculiar brand of philosophy sought to find the “foundational essence” (Grundwesen) of things by “clinging to mystical experience as intimately as possible.”[17] Gerda Walther was a woman who “experienced ‘something’” (Rahner). Forever changed by a mystical event that struck her like lightning on a train ride back to Freiburg in the winter of 1918 after visiting her seriously infirm father, Walther witnesses to the radical otherness and elsewhere of divinity:

Now, a bright inner glow (innerer Lichtschein) was streaming toward me from that immeasurable distance; it surrounded me completely. All the suffering I had ever experienced seemed to have been extinguished, as if it had never happened, as if I had heard only being told about it, like about something that had happened to a stranger. From my very depths, I felt born anew and transformed. I did not know anything anymore about myself and my surroundings; I only felt that warm flood of love which had taken me up, I saw only that spiritual light that had penetrated me. Then, entirely gradually, that sea of light and warmth began to retreat again, slowly and gently releasing me from itself, but in such a way that I was still held by it as if from a distance for a long time and such that I did not again plunge into the infinite dark space without support and without strength.[18]

This incisive testimony of Walther gives us a baseline experience around which to consider the peculiar characteristics of mystical givenness that we discover at the heart of Christian prayer. The classic contrast between light and darkness is indicated, with concentrated attention on the interior dimensions of the oncoming delivery of illuminating givenness. Suffering becomes a stranger to the inner glow (innerer Lichtschein) that enters and envelopes Walther like a protective fortress. What gives itself touches the deepest recesses of her consciousness by introducing a counterconsciousness of intimately charitable hospitality.[19] The spiritual “sea of light” eventually subsides with gradual tenderness only to leave a residue of enclosure that secures her against a relapse into the vacuous and dreadful dark abyss that would otherwise drape the dim tarpaulin of nihilism over any ounce of her intentionality left to believe, to trust, and to give.

In more focused phenomenological language, Walther describes such an experience as an “inner joining” or an “inner unification” (innere Einigung), with reference to an ego-altering interpersonal encounter. She describes this inner joining further in her dissertation as “a warm, affirmative wave of greater or lesser impact.”[20] Participants are left with a “feeling of mutual belonging” (Gefühl der Zusammengehörigkeit) through an evolved we-consciousness “growing together” (Zusammenwachsen) in which there is a profound sense of inclusion and empathic shared lived experience.[21] Turning to the special case of mystical experience vis-à-vis God that lives at the heart of Christian prayer, Walther describes this interpersonal encounter as “a living experience of ‘the real (leibhaftig) presence’ of God.”[22] When consciousness is flooded by the real presence of God, the ego is provoked to empty itself outward in imitatio Christi.

Just as the three Persons of the Most Holy Trinity empty themselves into a human soul, the soul in turn is propelled to empty himself into the world of souls that surrounds him, and to empty himself in adoration of the Trinity, thereby liberating the soul from the diabolical contraction of “being trapped in the immanance of the I.”[23] Walther insists that “the I will lapse into ruin and wants to do so, if it does not find something else (Es).”[24] By the inversion of the ego’s delusional abandonment to its dissembled self-sufficiency, the self lives to the degree that it dies in its self-forgetfulness and abandonment to the real presence of God that gives itself in the mystical synaxis of the Catholic Church.[25]

Conclusion

Altogether, as indicated by Walther, what is most decisive for a phenomenology of prayer is the givenness of divine agency. Whether in a caravan to Damascus, a chariot to Ethiopia, or a train to Freiburg, Jesus Christ crashes in on the scene of the soul without warrant or warning. His call echoes down the corridors of conscience “like a champion joyfully runs his course. From one end of the heavens he comes forth; his course runs through to the other; nothing escapes his heat” (Psalm 19:6–7). In this short essay, we have considered the basic steps of phenomenology, the status of phenomenology within Catholic thought today, and some preliminary ideas that begin to outline a Christocentric phenomenology of prayer, with special reference to the life and work of Gerda Walther.

Beyond a mere generic “theological turn,” may phenomenology continue to undergo a specific “Christological turn” that will unite phenomenology and metaphysics in a methodological “inner joining” (innere Einigung) while allowing each method to remain itself, though always in proximity to the irreducible other. A careful Catholic methodology commits to gathering up so many fragments in its attempt to think toward the whole. Authentic Catholic thought begins and ends with Christ as its Alpha and Omega through an abandonment of thought itself to him who abandoned himself as Logos to us. Without this mutual abandonment of intertwining thought, clear and cogent contemplation goes missing. A Christocentric phenomenology of prayer is successful to the measure that it brackets the concupiscent natural attitude, receives and contemplates what gives itself by itself, and finally interprets and describes what gives itself in lived experience according to the obedient hermeneutics of the divine Expositor (Ausleger; Hans Urs von Balthasar). As we have learned from Gerda Walther, the self cannot become itself without something else (Es) intruding.

[1] Karl Rahner, “Christian Living Formerly and Today,” in Theological Investigations VII, trans. David Bourke (New York: Herder & Herder, 1971), 15.

[2] See Edmund Husserl, Logical Investigations, Vol. 1, trans. J. N. Findlay (New York: Routledge, 1970), 168; and Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, Vol. 1, trans. F. Kersten (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 35–36.

[3] Edmund Husserl, 1907 Göttingen Lecutres, published as The Idea of Phenomenology, trans. William P. Alston and George Nakhnikian (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1990), 41. Cf. ibid., 41, where Husserl says that the special character of phenomenology “consists in the fact that it is the analysis of essence and the investigation into essence in the area of pure ‘seeing’ thought and absolute self-givenness. That is necessarily its character; it sets out to be a science and a method which will explain possibilities—possibilities of cognition and possibilities of valuation—and will explain them in terms of their fundamental essence.”

[4] Martin Heidegger, Towards the Definition of Philosophy, trans. Ted Sadler (London: Athlone, 2000), 188.

[5] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “What Is Phenomenology?”, Cross Currents 6:1 (1956), 59–70.

[6] To read additional accounts of the basic steps of phenomenology, see Donald Wallenfang, Phenomenology: A Basic Introduction in the Light of Jesus Christ (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2019); Donald Wallenfang, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist: An Étude in Phenomenology (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017), 5–21; Donald Wallenfang, Human and Divine Being: A Study on the Theological Anthropology of Edith Stein (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017), xxiii–xxiv; and Donald Wallenfang’s “Pope Francis and His Phenomenology of Encuentro,” in John C. Cavadini and Donald Wallenfang, Pope Francis and the Event of Encounter (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2018), 58–62.

[7] See Edmund Husserl’s 1907 Göttingen Lecutres, published as The Idea of Phenomenology, trans. William P. Alston and George Nakhnikian (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1990), 50: “Thus as little interpretation as possible, but as pure an intuition as possible (intuitio sine comprehensione). In fact, we will hark back to the speech of the mystics when they describe the intellectual seeing which is supposed not to be a discursive knowledge.”

[8] John Paul II, Address to a Delegation of the World Institute of Phenomenology of Hanover (2003).

[9] For a beginner’s guide to classical metaphysics, see Donald Wallenfang, Metaphysics: A Basic Introduction in a Christian Key (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2019).

[10] Karol Wojtyła, Über die Möglichkeit eine christliche Ethik in Anlehnung an Max Scheler zu schaffen, ed. Juliusz Stroynowski, Primat des Geistes: Philosophische Schriften (Stuttgart-Degerloch: Seewald, 1980), 196. English translation taken from Michael Waldstein’s Introduction of John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2006), 75.

[11] For relevant magisterial passages treating the heresy of “phenomenalism,” see Pius X, Pascendi dominici gregis (1907), 6–17, 25, 30, 39, and John Paul II, Fides et ratio (1998), 54, 59, 82–83.

[12] See Jean-Luc Marion, The Visible and the Revealed, trans. Christina M. Gschwandtner, et al. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 56–57: “(2) Since intuition gives in the flesh, the Kantian caesura between the (solely sensible) phenomenon and the thing-in-itself must disappear. (3) Since intuition alone gives, the I (even the transcendental and constituting I) must remain by and hence in an intuition . . . intuition as givenness—always precedes the consciousness of it, which we receive as if after the fact.”

[13] Even the father of phenomenology himself was guilty of bracketing things theological out of the scope of phenomenological investigation. See Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, Vol. 1, trans. F. Kersten (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 134: “What concerns us here, after merely indicating different groups of such rational grounds for <believing in> the existence of an extra-worldly ‘divine’ being is that this being would obviously transcend not merely the world but ‘absolute’ consciousness. It would therefore be an ‘absolute’ in the sense totally different from that in which consciousness is an absolute, just as it would be something transcendent in a sense totally different from that in which the world is something transcendent. Naturally, we extend the phenomenological reduction to include the ‘absolute’ and ‘transcendent’ being. It shall remain excluded from the new field of research which is to be provided, since this shall be a field of pure consciousness.” Heidegger followed suit in his 1927 Tübingen lecture entitled “Phenomenology and Theology” where he regarded theology as an “ontic positive science” and philosophy as “the science of being, the ontological science.” Heidegger names faith only “a specific possibility of existence” and “in its innermost core the mortal enemy of the form of existence that is an essential part of philosophy and that is factically ever-changing. Faith is so absolutely the mortal enemy that philosophy does not even begin to want in any way to do battle with it.” See Martin Heidegger, Pathmarks, ed. William McNeill (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 40–41, 53. Gerda Walther speaks of this break of philosophy from the fullness of reality (that would include theological data and divinely revealed mysteries) as a modern “fall of man” (Sünderfall). See Niamh Burns, “A Modernist Mystic: Philosophical Essence and Poetic Method in Gerda Walther (1897–1977),” German Life and Letters 73:2 (2020), 246–69, 251. Cf. Andrew Prevot, Thinking Prayer: Theology and Spirituality amid the Crises of Modernity (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2015), 112, where he speaks of a “(typically modern) inhospitality toward prayer.”

[14] David Tracy, The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism (New York: Crossroad, 1981), 112: “I find myself in another realm of authentic publicness, a realm where ‘only the paradigmatic is the real.’” Cf. Donald Wallenfang, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist: An Étude in Phenomenology (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017), 205, 233–36.

[15] See Niamh Burns, “A Modernist Mystic: Philosophical Essence and Poetic Method in Gerda Walther (1897–1977),” German Life and Letters 73:2 (2020), 246–69, 259: “Walther refers to a ‘Kindheitszustand’ [‘condition of childhood’] in which ‘Geist,’ [‘Spirit] ‘Seele,’ [‘Soul’] and ‘Leib’ [‘Body’] have not yet become distinct and distinguishable. She means this literally: it is a state she identifies in childhood experience . . . This originary harmony . . . is unconscious and ‘unschuldig’ [innocent], and many lament its loss.” Translations my own.

[16] Walther’s Introduction and Chapter 1 of Phänomenologie der Mystik have been translated by Rodney K. B. Parker and published in Antonio Calcagno, ed., Gerda Walther’s Phenomenology of Sociality, Psychology, and Religion, 115–33.

[17] See Niamh Burns, “A Modernist Mystic: Philosophical Essence and Poetic Method in Gerda Walther (1897–1977),” German Life and Letters 73:2 (2020), 246–69, 248. Cf. ibid., 248: “Walther’s phenomenology of experience, through which one’s personal ‘Grundwesen’ unfolds, is based on the idea that the self is made up of what she calls ‘Ichzentrum,’ which undertakes conscious reflection, and the space ‘behind’ that act of reflecting, the ‘Einbettung’ or ‘Hintergrund’ through which the self experiences a non-reflective, fluid mode”; and ibid., 258: “Walther’s phenomenological reflection combines a ‘[rationale] Denkmethode’ [‘rational method of thought’] with an enacted and caring ‘embrace’ of mystical experience.” Gerda Walther, Phänomenologie der Mystik (Olten: Walter, 1955), 1–2: “diesem mystischen Erleben wollen wir uns in unserer Untersuchung so innig wie möglich anschmiegen.” Translation my own above.

[18] Gerda Walther, Zum Anderen Ufer: Vom Marxismus und Atheismus zum Christentum (Bonn: Otto Reichl Verlag, 1960), 225, as translated in Kimberly Baltzer-Jaray, “Phenomenological Approaches to the Uncanny and the Divine: Adolf Reinach and Gerda Walther on Mystical Experience,” in Antonio Calcagno, ed., Gerda Walther’s Phenomenology of Sociality, Psychology, and Religion, 154.

[19] On the concept of “counterconsciousness” or “counter-intentionality,” see Emmanuel Levinas, Entre Nous: On Thinking-of-the-Other, trans. Michael B. Smith and Barbara Harshav (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 58, and Jean-Luc Marion, Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness, trans. Jeffrey L. Kosky (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 266–67.

[20] Gerda Walther, “Ein Beitrag zur Ontologie der sozialen Gemeinschaften (mit einem Anhang zur Phänomenologie der sozialen Gemeinschaften)” (1921), 34, as translated by Daniel Neumann in “Inner Joining in Gerda Walther (1897–1977),”

[21] See Marina Pia Pellegrino, “Gerda Walther: Searching for the Sense of Things, Following the Traces of Lived Experiences,” in Antonio Calcagno, ed., Gerda Walther’s Phenomenology of Sociality, Psychology, and Religion, 20.

[22] Ibid., 21. Cf. Gerda Walther’s Introduction of Phänomenologie der Mystik, trans. Rodney K. B. Parker, in Antonio Calcagno, ed., Gerda Walther’s Phenomenology of Sociality, Psychology, and Religion, 118: “What a phenomenology of mysticism cannot and will not attempt to do is give a possible natural, causal explanation or reduction of mystical facts according to the principles of natural science . . . . For the mystical is an irreducible, primordial phenomenon, a basic, primordial givenness that cannot be traced back to or derived from some other phenomena, such as colours, sounds, values, and so on.”

[23] Ibid., 22.

[24] Gerda Walther, Phänomenologie der Mystik, 144, as translated in Marina Pia Pellegrino, “Gerda Walther: Searching for the Sense of Things, Following the Traces of Lived Experiences,” in Antonio Calcagno, ed., Gerda Walther’s Phenomenology of Sociality, Psychology, and Religion, 23.

[25] See Anthony Steinbock, Moral Emotions: Reclaiming the Evidence of the Heart (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2014), 31–66, on the notion of the self-limiting and self-dissembling character of pride as a “moral emotion.”