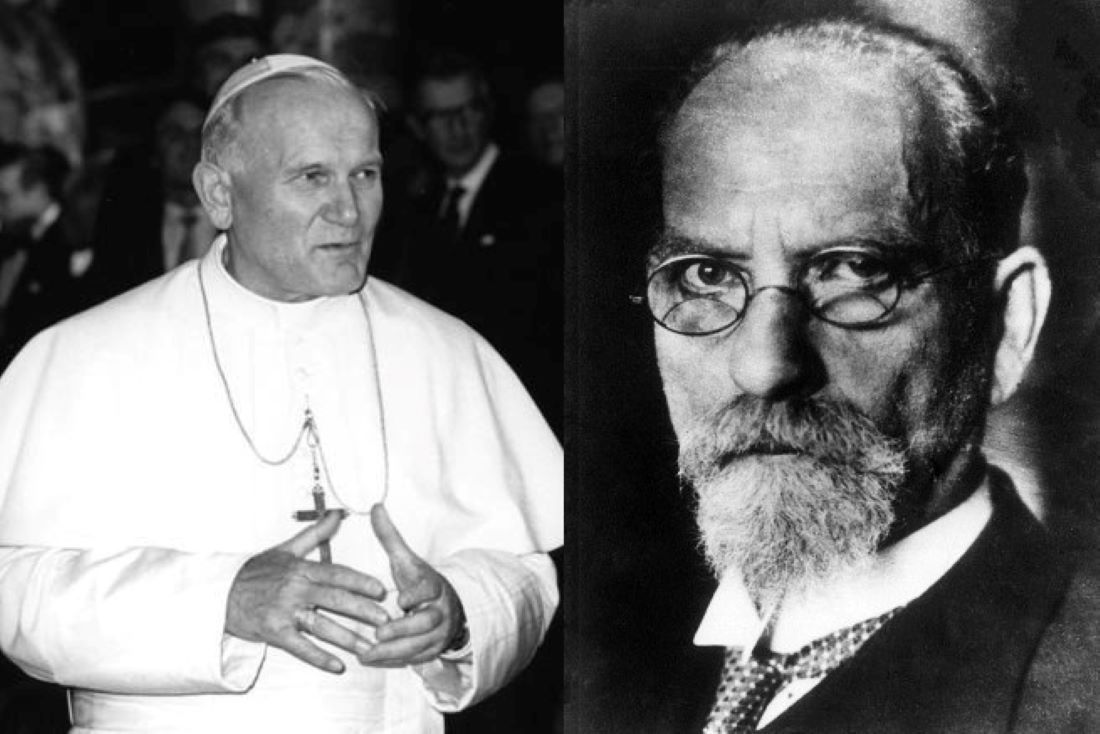

Two years before his 1978 appointment as Pope John Paul II, the Polish archbishop Karol Wojtyła described his theories of human nature as “phenomenological.” An ethics professor as well as a priest, Wojtyła spent the decade before his papal appointment writing books and essays that joined insights from the German-born philosophy of phenomenology with Church doctrine. Most notably, his 1969 masterwork The Acting Person—quintessentially phenomenological in its dense descriptions of human experience—argued that man’s worldly activity depended on faith in God for its ultimate meaning. His subsequent papal encyclicals—especially Laborem Exercens (1981) on the spiritual dimensions of work—carried forward this allegiance by deriving moral recommendations from the extended analysis of modern life. And Solidarity, the Polish trade union, was a phenomenological concept in Wojtyła’s thought before it became the name of an anti-communist movement. Yet for all of John Paul II’s celebrity, very few people know what phenomenology is or its influence on recent history.

Edward Baring’s superb new book, Converts to the Real: Catholicism and the Making of Continental Philosophy, tells the story of phenomenology's transformation from an obscure turn-of-the-century academic theory into Europe’s dominant continental philosophy by the 1950s—and shows in the process that Wojtyła’s blend of religion and phenomenology was not unique. On the contrary, Catholic thinkers, who had lost their cultural supremacy in the modern age, regularly engaged with phenomenology in the hope of renewing their relevance. In it, they saw a philosophy with academic pedigree that was also an ally in the battle against secular materialism, a perfect partner to usher Catholic thought back into the intellectual mainstream. Yet in many ways it was phenomenology that benefited the most. Catholic dissemination, Baring argues, turned phenomenology into the European philosophy, one with continental reach and resounding influence.

Much of this story is unknown today, partly due to phenomenology’s inaccessibility. The movement’s founder, Edmund Husserl, produced philosophic tomes written in a kind of “phenomenologicalese” that obstructs not only broad public access, but most academics as well. With its “tongue-twisting name” (as one early proponent put it), proliferous neologisms, and vast descriptions of experiential minutiae, phenomenology seemed to shut itself off from the world, even as it claimed to offer a new method for understanding worldly reality. As a result, while its philosophical offspring (existentialism, postmodernism) achieved mainstream recognition, phenomenology languished in academic obscurity.

While Baring ably traces phenomenology’s philosophical ascendance, one might still wonder why it matters outside of the rarefied world of the academy. Part of the answer is that through Catholic channels phenomenology became an intellectual source for ideas about human rights, Christian Democracy, and the European Union. But its full social significance was only realized in the 1970s by East European dissidents, who mixed phenomenology and religion in their criticism of communist regimes. Although the only East European case that Baring discusses is Poland, a fuller account of the dissident use of phenomenology is essential to understanding not only the importance of his story but also the significance of phenomenology in the 20th century.

+

Over the past decade, scholars have begun to chart the considerable involvement of Catholic thinkers and activists in 20th century political events. Piotr H. Kosicki has shown their fraught engagement with Stalinist authorities in postwar Poland. John Connelly has recounted Catholic efforts to overcome European anti-Semitism. Samuel Moyn has traced their role in conceptualizing human rights. And James Chappel has documented Catholic stewardship of Christian Democratic parties, which rebuilt postwar European societies.

Baring adds to this story by showing how Catholic networks contributed to the rise of one of Europe’s most influential recent philosophies. The pairing of Catholicism and modern philosophy may at first appear counter-intuitive. As Martin Heidegger’s ontology (plus his controversial Black Notebooks) and Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism suggest, continental European thought, especially in its phenomenological variant, was often openly secular. Yet Baring shows that phenomenology and Catholicism in fact offered each other reciprocal services. Catholic dissemination helped phenomenology reach a wider audience and avoid academic myopia, while phenomenology provided Catholics with a rich understanding of modern experience that Church thinking lacked, helping them to engage more readily in contemporary life.

But the relationship was never easy. In Baring’s telling, it had the feel of a courtship, with interest and infatuation giving way to betrayal, break-up, and reconcilement.

The flirtation began soon after the 1901 publication of Edmund Husserl’s masterwork, Logical Investigations, which Catholic thinkers embraced for its apparent commitment to “philosophical realism.” What did this term mean? Like much of Western philosophy, phenomenology tried to determine how we know what is real. In the modern era, many philosophers have treated reality as a mental construct, something created by the human mind. The most well-known examples of this “idealist” tendency are Descartes, who rejected empirical knowledge gained through the senses in favor of certainties deduced in the mind (“I think, therefore I am”); and Kant, who cast the external (or noumenal) world outside of human ken, in a realm of which we have no certain knowledge.

Husserl, by contrast, argued that every thought or perception is directed at some object (or “phenomenon”—hence phenomenology) external to it. Every mental act is “intentional,” to use his signature term, because human consciousness is always consciousness of something in the real world. Subject and object, self, and world—these are not discrete entities separate from one another, but parts of the unified continuum that we often call experience. Far from being a filter or veil that blocks access to reality, therefore, experience is in fact the royal road to it. And phenomenology, through its careful analyses of experience, could lead us to “the things themselves” (to cite the movement’s rallying cry).

Husserl’s realism appealed to Catholic thinkers because it seemed to align with their own faith in the actuality of God’s creation. For centuries, the Church had rejected modern culture, claiming that it elevated man over God as the source of truth and thereby encouraged atheism, egotism, and moral relativism. The modern emphasis on individualism, Catholics complained, not only weakened religious faith but also undermined family and community bonds. As part of its anti-modernism, the Church espoused its own version of philosophical realism, which it drew from medieval thought and held in lonely opposition to contemporary idealism. Husserl’s realism gave them hope in the possibilities of at least one strand of modern thought.

Yet, Catholic outreach to phenomenology could not have occurred without a shift in Church policy. Faced with a dwindling number of believers, Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) introduced a series of reforms meant to engage the Church in the modern secular world. Although these changes caused internal dispute, modernist Catholics at the turn of the century now felt they could explore recent philosophy with official approval. In this context, phenomenology seemed to offer rich opportunities for dialogue, and Catholic thinkers discussed and debated Husserl’s ideas throughout the first decade of the 20th century.

+

But infatuation soon turned to disappointment. In 1913, after a ten-year silence, Husserl published a new volume, Ideas, in which the realism of his earlier conception—the view that experience could reveal objective truth—gave way to a “transcendental idealism” that seemed to present the world as an emanation of “pure consciousness.” Husserl defended this shift as a deepening of his former program, but Catholic thinkers saw it as a betrayal—a return to the Kantian thought he had once discarded. Their romance with phenomenology appeared over.

Many of Husserl’s students were similarly distraught. They spent subsequent decades trying to rescue phenomenology from the treason of its founder and return to its original realism. But their effort was not enough for skeptical Church officials. By the eve of World War I, progressive Catholics who had championed dialogue with phenomenology were on the defensive due to Pius X’s condemnation of theological modernism. Although phenomenological ideas continued to circulate among Catholic thinkers and activists, a new institutional opening to modern philosophy would have to wait until the 1930s, when the rise of Fascism and Stalinism sent the Church looking for ways to attract laypeople away from totalitarian promises.

With many Catholic activists warning that intellectual rigidity seemed irrelevant in an age of economic crisis and political polarization, Church modernists once again turned to phenomenology to make sense of contemporary needs. Their reconciliation was chastened, however, by past experience not only with phenomenology’s philosophical equivocation, but also with its religious ambiguity.

On the one hand, Husserl’s school had proved its ability to shepherd doubters to faith and non-Catholics to conversion. Many of its practitioners were openly devout: Max Scheler (who first applied Husserl’s insights to social and ethical problems) and Edith Stein (a Jewish-born philosopher, nun, and saint martyred at Auschwitz) were Catholic converts, while Husserl and Adolf Reinach (who proposed an early phenomenology of law) were baptized Protestant. But phenomenology could also work in reverse, turning believers against the faith, as Scheler’s 1922 apostasy epitomized. Heidegger’s journey from young theologian to secular apostle of Being provided another warning of phenomenology’s propensity to mislead.

While these apprehensions tempered phenomenology’s allure, they did not douse it, and in the years surrounding World War II phenomenology became the preferred philosophical sparring partner for a new generation of Church moderns. The revival of Catholic phenomenology centered on a set of French thinkers—notably Emmanuel Mounier and Jacques Maritain—who strove to update the reception of Church teaching and define a Catholic political stance, efforts that involved them in considerable controversy: Mounier at times backed Fascists and Stalinists, even collaborating with the Vichy regime before joining the opposition. Maritain was more measured, but he too arrived at anti-Fascism after earlier support for monarchy.

These were not individual idiosyncrasies. While the Church ultimately condemned both Communists and Fascists, it also disliked the liberal capitalist alternative, whose materialism and individualism it blamed for the social and economic breakdown that encouraged extremism. Catholic thinkers and officials in the 1930s often supported softer forms of authoritarian rule that claimed to protect religious values. Their fascination for Austria’s anti-Nazi dictator Engelbert Dollfuss, who crushed Vienna’s socialists in a bloody civil war, is a case in point. It was not until the late 1930s that the Church finally realized that soft authoritarianism was no shield against fascism.

Despite these political blunders, modernist debates over religious and social doctrine continued to intrigue Catholic activists—including the young Wojtyła—who were hungry to engage with laypeople in war-torn Europe. After surviving World War II in his native Krakow, the newly ordained Wojtyła studied at the Angelicum University in Rome under the arch-conservative Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange even as he immersed himself in new methods of pastoral activism and intense study of Max Scheler’s phenomenology of morals. His early career, in other words, embodied the tensions between tradition and modernity that confronted the Church as a whole.

In the postwar world, as the Church sought to participate in European recovery, Catholic thinkers continued to explore secular philosophy for ideas on engaging with modern society. Even the avowedly atheist Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose existentialism presented a godless universe, drew Catholic interest, partly because they relied on phenomenological categories that were familiar to modern Church thinkers. This commingling of modern Catholicism and phenomenological existentialism reveals another implication of Baring’s book: that Europe’s secular culture often has hidden religious roots. While other scholars have demonstrated Catholic influences on 20th century political events, Baring finds their residue even in Sartre’s atheist Left Bank.

In a fitting emblem of the Catholic-phenomenological partnership, Baring’s penultimate chapter recounts the story of Herman Leo van Breda, the priest who rescued manuscripts of the Jewish-born Husserl from likely destruction in Nazi Germany by smuggling them to safety in Belgium. After the war, these became the basis of a new research center at the Catholic University of Leuven, financed in part by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). To this day, it is a hub for phenomenological research.

+

As this history suggests, phenomenology was more than just a 20th century master philosophy. It was also an influential social theory with three broad planks. First, phenomenologists sought to defend insights derived from concrete personal experience—indeed, the sanctity of individual persons themselves—against a variety of threats arising in modern mass societies: authoritarian domination, technocratic disdain, and bureaucratic anonymity, to name a few. Second, they sought to reorient modern life away from extreme individualism and toward community involvement, which they considered an essential human need. And finally, they tried to direct individuals and communities toward objective moral values that could be discerned, they believed, through the close analysis of conscience and experience. Combined, these convictions led them to advocate for communities of purpose that united people around common ethical commitments.

This program had considerable appeal. In the 1910s and 1920s, it fed anti-capitalist, nationalist, and pacifist attitudes among German Catholics. By the 1930s, it contributed to Catholic anti-Nazi activism in Vienna. And starting in the 1960s, East European dissidents drew on phenomenology to mount their anti-communist campaigns.

The East European tale is particularly striking. In addition to Wojtyła, Václav Havel (the Czech playwright-turned-president) credited the “atmosphere” of phenomenology for fueling his advocacy of Charter 77, a Czechoslovak dissident movement that publicized the communist government’s human rights violations. As opposed to official Marxism, which subordinated individuals to the laws of history, phenomenology valued personal experience and moral insight as sources of knowledge.

Jan Patočka, a Husserl and Heidegger student who became Czechoslovakia’s leading philosopher, expounded similar phenomenological themes in two manifestoes praising the Charter’s defense of human conscience against authoritarian state power. He paid with his life for serving as a Charter spokesman, falling fatally ill after a lengthy police interrogation.

Phenomenology’s social and political implications were already apparent to Husserl’s earliest followers, who believed their work could help to reform politics, improve legal theory, and combat what they saw as the degeneracy of capitalism. In the 1930s, Husserl himself, steadily isolated under Nazi rule, warned that modern science had escaped people’s understanding, forcing them to cede control to experts. The resulting sense of powerlessness increased the lure of cynicism and demagoguery. In response, Husserl called on philosophers to act as “functionaries of mankind” by helping to ensure that technical advancements not only improved efficiency but also fostered human community and well-being.

But the real pioneer of social phenomenology was Max Scheler. A Catholic convert, Scheler claimed in 1913 that feelings of right and wrong, like all intentional acts, revealed external moral truths—in this case, the existence of objective values such as goodness and virtue—that modern capitalism subverted by glorifying creature comforts over ethical and spiritual values. It was Scheler who first employed the socialist concept of solidarity within the phenomenological oeuvre, contrasting it favorably with modern self-interested individualism.

To make sense of these social and ethical claims, one must understand another key feature of phenomenological thought. As opposed to empiricists like David Hume, who argued that reality consists only of things we can verify with our senses, phenomenologists believed we could look beyond the visible world in order to identify the essences or innate necessities of things perceived, those characteristics that make something uniquely what it is. Moral values, they maintained, were part of the world’s essential makeup, just as real as physical things.

While the belief in essences is hard to defend on rational grounds, it had eminently practical implications. By revealing, for example, that a person’s essence was not limited to his or her current circumstances, phenomenologists argued that people could alter their situations and that social reality encompassed not only facts that exist in the world, but also unfulfilled possibilities that could just as well exist. A person, they maintained, always has more potential than is apparent at any given moment, and this unrealized promise is part of their essence, part of who they are.

The insight that reality is greater than mere factual circumstance had extraordinary implications in a Europe where dictatorships regularly claimed a monopoly on truth. It could encourage people to imagine alternate social and political systems, to live “as if”—In the poignant phrase of Czechoslovak dissidents—they were free to make decisions regarding policy and leadership. For many followers, phenomenology became a philosophy of liberty, one that could reveal human possibilities and defend man’s freedom.

During the interwar period, Scheler’s followers took these lessons to heart. The Catholic youth movement, for example, which boasted 1.5 million members, embraced his call to renew a cynical and war-weary Weimar Republic by reorienting it toward Christian values. And in 1930s Vienna, Dietrich von Hildebrand and Aurel Kolnai, both Catholic converts, invoked objective moral values to condemn Nazism for elevating blood and soil over ethics and spirit. Though they could not stop Austria’s embrace of Hitler, their ideas influenced Christian and conservative circles after the war.

A similar blend of religion and philosophy was found among East European dissidents in the 1970s. As the Czech writer Eva Kantůrková remarked, if Charter 77’s “main philosophical trend [was] phenomenology,” it drew its “ethics from Christianity.” In Poland, Wojtyła and Józef Tischner (the unofficial chaplain of the Solidarity trade union) also joined phenomenology with Catholic teaching in their criticisms of communist rule.

In a sermon delivered at Solidarity’s first national convention in 1980, Tischner sought to prise the Marxist category of work away from a workers' state that, in his view, reduced labor to material productivity. Instead, Tischner used phenomenological analyses to cast work as a fundamental aspect of human dignity and community life. Through our work, we exhibit our care and concern for one another, providing for each other’s needs and expressing core values. Polish communism, by contrast, turned work into drudgery, a message amplified by John Paul II in Laborem Exercens (1981). The irony, of course, is that Marxism itself rests on an analysis of alienated labor.

+

For these reasons, phenomenology’s history is not only of interest to philosophers. When communism fell in Eastern Europe, many commentators anointed the former dissidents as a liberal vanguard, steering their societies toward party democracy and market economy. But this view displays Western triumphalism more than anything else. The phenomenological tradition that infused dissident thought—and, through Pope John Paul II, came to influence the globe—had a far different agenda.

Over the course of a century, Husserl’s brainchild developed from a rigorous philosophy of experience into a rich defense of personal and communal freedoms against autocratic control—by governments above all, but also by anonymous social and economic systems such as today’s neoliberalism, which subordinates civic decisions to market forces.

Of course, phenomenology’s Czech and Polish disciples condemned Soviet Bloc dictatorship. But Wojtyła, Havel, Tischner, and Patočka also questioned—as had phenomenologists before them—Western consumer societies, which, according to Havel, exhibited a “willingness to surrender higher values” before the “temptations of modern civilization.” The “grayness” of Eastern Europe, he warned, stood as “an inflated caricature of modern life,” a signal to “the West” of “its own latent tendencies” to dismiss conscience in the pursuit of material advancement. Tischner and Wojtyła concurred: both communism and capitalism, they feared, forsook human dignity in the rapacious pursuit of higher production.

Rejecting both Soviet communism and Western capitalism, East European dissidents sought to nurture new societies of hope and purpose. Solidarity, not laissez-faire; community purpose, not individual greed—these were their mantras. Only a vigilant focus on higher social and moral values, they believed, could maintain free and vibrant societies.

In some ways, their concerns are still ours. Husserl’s 1930s lament that modern science had abandoned the human “lifeworld”—supplying us with explanations of nature, but precious little purpose or meaning—resonates with today’s fears about the technocratic leveling of our societies. What are the roles of civic activism and democratic deliberation in a world of expert management? What is the appropriate balance between administrative supervision and personal choice in running our lives? These are still potent questions.

But does phenomenology offer satisfactory answers? As opposed to technocrats governing according to fixed laws, Husserl’s philosopher-functionaries act as cultural stewards, trying to defend human experience as a source of knowledge and orient mankind toward ethical truths. But they are still an elite clerisy. At the extreme, phenomenology could express contempt for the mundane preoccupations of daily life, which act as so many distractions from our higher calling.

In addition, after the collapse of communism, phenomenology’s tendency to favor moral appeals over political jockeying—Havel famously refused to join a political party—sometimes hobbled activists working within its precincts. Does an overemphasis on morality, we might ask, stifle the partisan debate and compromise needed for democracy to function?

Baring’s history helps to explain these successes and constraints. On the one hand, phenomenology’s partnership with Catholicism helped to secure it a continental hearing. And few would doubt that moral and religious conviction bolstered the fortitude needed by anti-regime dissidents. However, the preference among phenomenological scions for standing above politics and speaking in the name of truth or morality—so powerful in the Soviet era—could seem condescending in a democratic age.

Yet, to dismiss phenomenology would be mistaken. For even as its votaries indulged in moralizing, they also defended civic pluralism, community engagement, and ethical commitment. One of the services phenomenology can perform today is to broaden our own political imagination, splayed between technocratic elitism and angry populism. It is one of the perversions of our neoliberal age that we have difficulty articulating freedom in anything but individual terms. Collectivist programs evoke a socialist bugbear, even though collectivism was never exclusive to that tradition. Yet as we struggle to find new political models, it is crucial to recall past conceptions of communal activism outside the socialist ambit.

Hence the importance of Baring’s history. East European dissidents drew on a long phenomenological past that offers a humane program distinct from both liberalism and socialism. The recovery of this tradition, with all its strengths and weaknesses, can feed contemporary political debates starved for new visions of collective purpose. Baring's book makes an original contribution to that goal.