One of Velázquez’s most enigmatic religious paintings, dating from his early Seville period, is also a bodegón, a secular representation of everyday life: the so-called Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (1618, London, National Gallery), wherein a foreground kitchen scene is fused—both formally and iconographically—with a background Biblical subject from which the work derives its title and meaning.[1]

In the foreground, an old woman gently admonishes a young servant girl who is clearly unhappy about her kitchen duties as she sullenly prepares a meal.[2] The convincing naturalism of this bodegón combined with the formal, almost liturgical, arrangement of the prominent still-life recalls the artist’s other masterpiece from that same year: The Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618, Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland).

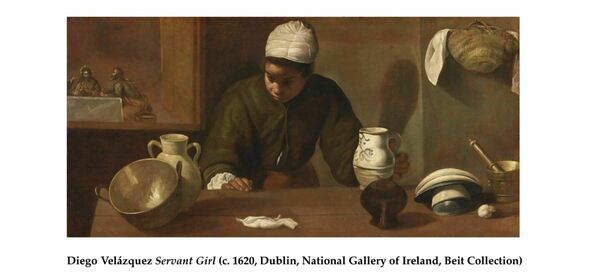

In each canvas the vivid description of the different surfaces and textures—the copper mortar, the peeled garlic, the fish, eggs, and earthenware jug—both solemnize and celebrate the tactile values of ordinary objects. The young servant, shown in the act of grinding garlic, recalls Velázquez’s Servant Girl (c. 1620, Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland, Beit Collection).

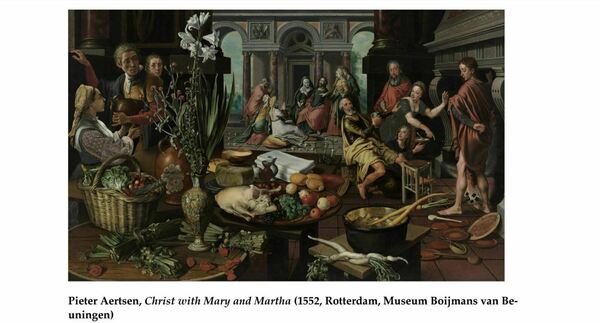

A deeper connection between the two paintings came to light in the 1930s as a result of a thorough cleaning.[3] In the upper-left background of the Beit canvas, a Biblical scene is represented as if seen through an opening in the wall.[4] That background subject is The Supper at Emmaus, wherein the resurrected Christ suddenly reveals himself to two unsuspecting disciples at table (Luke 24: 30-31). The connection with the foreground scene is simple and straightforward: the servant girl, shown in the adjoining kitchen at the Emmaus inn, is unaware of the miracle taking place in the next room. Her counterparts may be found throughout representations of that biblical subject in Italian and Netherlandish art: the servant or innkeeper who remains oblivious to the divine revelation in the midst of everyday life.[5] The fact that Velázquez has chosen to give her the place of greater prominence in this painting reflects a northern Mannerist tradition, exploited by Pieter Aertsen, in which the biblical subject is relegated to an adjoining room in the background, seen through an opening in the wall, while the foreground is devoted to a colorful genre scene.

It was this tradition that Velázquez evidently followed—perhaps through an engraving or copy of Aertsen’s 1552 Christ with Mary and Martha (Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen)[6]—in the London painting of the same subject.

In the London canvas, Velázquez did more than adapt the Northern Mannerist device to his early biblical bodegón. Here he exploited the compositional inversion to illuminate and underscore the meaning of the subject in a way that his Spanish contemporaries would not have failed to grasp. The point of his Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, I submit, depends upon the precise iconographic relationship between foreground and background. Their vivid juxtaposition charges the bodegón both psychologically and theologically.

Mary and Martha of Bethany were the sisters of Lazarus, whom Jesus raised from the dead. The Evangelist Luke tells of Christ’s visit to their home in Bethany—and their contrasting ways of serving him:

Now it came to pass, as they went, that he entered into a certain town; and a certain woman named Martha received him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who, sitting also at the Lord’s feet, heard his word. But Martha was busy about much serving. She stood and said, “Lord, hast thou no care that my sister hath left me alone to serve? Speak to her therefore, that she help me.” And the Lord answering said to her, “ Martha, Martha, thou art careful and art troubled about many things. But one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her (Luke 10: 38-42).

Martha’s story does not end here. A woman of faith, she chose to follow Jesus. It was she who summoned him to the aid of her brother Lazarus, who had fallen ill and (as yet unbeknownst to her) had died. Her faith resulted in the raising of Lazarus, the most dramatic miracle performed by Christ. Throughout the Middle Ages, however, the story of Mary and Martha was invoked by scriptural commentators as signifying the preeminence of the contemplative over the active life. Martha represented the laity devoted to a life of toil and labor; Mary stood for the contemplatives (nuns and monks alike) who removed themselves from worldly cares to worship Christ without distraction. The latter, according to the commentators, had chosen the higher calling.

By the sixteenth century this traditional, hieratic separation of the active and contemplative life underwent a profound revolution. In the North, Erasmus of Rotterdam challenged it with a phrase that rocked the ecclesiastical foundations of the already fragile medieval order: “Monachatus non est pietas”—wearing a monk’s habit does not make one pious. Those foundations finally cracked when the Augustinian monk Martin Luther renounced his vows in a final break with Rome.

Yet the Protestants were not alone in their rejection of the typological exaltation of Mary at the expense of Martha. Within the Catholic Church there arose three Spanish champions of the Faith, three towering reformers, later canonized as saints, who spearheaded the Catholic Reformation: Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, and two Carmelites—John of the Cross and Teresa of Ávila. In their crusading zeal, all three combined a deeply mystical spirituality with an indefatigable practicality. In their lives as in their writings, they reinterpreted the respective roles of Mary and Martha by coordinating them with equal emphasis on the active and meditative aspects of Christian spirituality.

It is against this Counter-Reformatory backdrop—both Spanish and Roman—that Velázquez’s original reinterpretation of the biblical subject must be understood, for the key to its meaning lies in the celebrated writings of Teresa—or “La Santa,” as she came to be popularly called even before her official canonization in 1622, four years after this painting. It is Saint Teresa who explains in her own writings how the gentle admonition to work—illustrated in the foreground—can be viewed as consonant with Christ’s famous biblical exchange with Martha in the background.

That Velázquez intended such a thematic parallel is underscored by his repetition of costume—the white headdress worn by both Martha and the old woman, together with their rhetorical gestures of raised right hands. The further repetition of the pottery jug in both scenes serves as a symbolic footnote signifying that the foreground represents an amplified gloss on the biblical background.

In the course of her travels among her newly reformed convents, Teresa often found the nuns unwilling—like Velázquez’s servant girl—to undertake joyfully the humbler tasks in convent life, such as working in the kitchen. Her classic admonition, recorded in her autobiography (Vida, ch. XXII) invokes both Mary and Martha in a most original and telling context:

The first thing I would say is that it is a little lack of humility to desire to raise one’s soul to heaven before the Lord raises it . . . to desire to be Mary before one has labored with Martha.[7]

It is Teresa’s characteristic insistence on humility and obedience that Velázquez evokes in the older woman admonishing the younger. For both Teresa and Velázquez the ultimate point of the Mary-and-Martha allusion was essentially encouraging, as it recalls another, far more famous saying of Teresa from her Book of the Foundations (Ch. V):

But my daughters, good heavens! Do not be disconsolate when obedience leads you to be concerned with external, worldly matters; understand that, if your task is in the kitchen, the Lord walks among the pots and pans, helping you in all things spiritual and temporal.[8]

“Entre los pucheros anda el Señor”—the Lord walks among the pots and pans. That saying of Teresa soon became common currency in Spain, where it still remains a popular proverb, with obvious application to daily life.[9]

It was Velázquez who first translated the proverb into paint. In his vivid gloss on the biblical story of Mary and Martha he offered nothing less than a visual parable on the virtue of humility and the holiness of ordinary labor. Teresa would have concurred wholeheartedly with this conjoining of the active and the contemplative in the sacred art of daily living. Entre los pucheros anda el Señor—with Martha as with Mary.

EDITORIAL NOTE: We would like to thank Gregory Wolfe of Slant Books for putting us in touch with the author of this piece.

[1] For the date of the painting, revealed in cleaning, see A. Braham, “A second dated Bodegón by Velázquez,” Burlington Magazine, CVII, 1965, 362-365.

[2] M. Sérullaz (Velázquez, New York, 1981, 68) maintained that the old woman is simply offering the young girl “culinary advice”—a view that runs counter to both the visual evidence and iconographic considerations.

[3] A version of the Beit canvas, without the Emmaus background scene, hangs in the Art Institute in Chicago.

[4] The background scene has also been interpreted as a framed picture or a mirror image, but the wall opening is most plausible: see A. Braham, 365. Braham concludes, however, that there is no more than a “general application” of the background scene to the foreground, which he calls a “bodegón moralisé.”

[5] See C. Scribner, “In Alia Effigie: Caravaggio’s London Supper at Emmaus, Art Bulletin, LIX, 1977, 375-382.

[6] M. Soria, in G. Kubler and M. Soria, Art and Architecture in Spain and Portugal, 1500-1800, Bradford (UK), 1959, 254.

[7] “El primero, ya comencé a decir es un poco de falta de humildad, de quererse levantar el alma hasta que el Señor la levanter . . . y querer ser María antes que haya trabajado con Marta.” (Vida, XXII, in Obras Completas, Madrid, 1966, 141b). I am grateful to Dr. Ray M Keck III for first bringing to my attention these apposite sayings of Teresa, translating them for this article, and stressing their widespread cultural currency in early seventeenth-century Spain down to the present day.

[8] “Pues, ea!, hijas mías, no haya desconsuelo cuando la obediencia os trajere templadas en cosas exteriores; entiende que, si es en la cocina, entre los pucheros anda el Señor, ayudán- dos en lo interior y exterior,” (Libro de las fundciones, Cap. V). Translated by Ray M. Keck. The first to apply this saying to the painting was M.S. Soria, “An unknown pairing by Velázquez,” Burlington Magazine, XCI, 1949, 129. Soria, however, did not link it to Teresa’s more specific saying (note 7, supra) about the relative roles of Mary and Martha. For a detailed analysis of the painting in the light of special veneration of Martha in seventeenth-century Seville and the ideal of blending the active and contemplative life, see Tanya J. Tiffany, “Visualizing Devotion in Early Modern Seville: Velázquez’s ‘Christ in the House of Mary and Martha’,“ The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 2005, 433-453.

[9] Ray M. Keck, supra, note 8. See also two recent excellent studies: T. Tiffany, Diego Velázquez’s Early Paintings and the Culture of Seventeenth Century Seville, University Park (PA), 2012, 108-119; and G. Knox, Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art: El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Amsterdam, 2019, 103-123 (with special focus on its relation- ship with the Beit Servant Girl, fig. 2, supra.