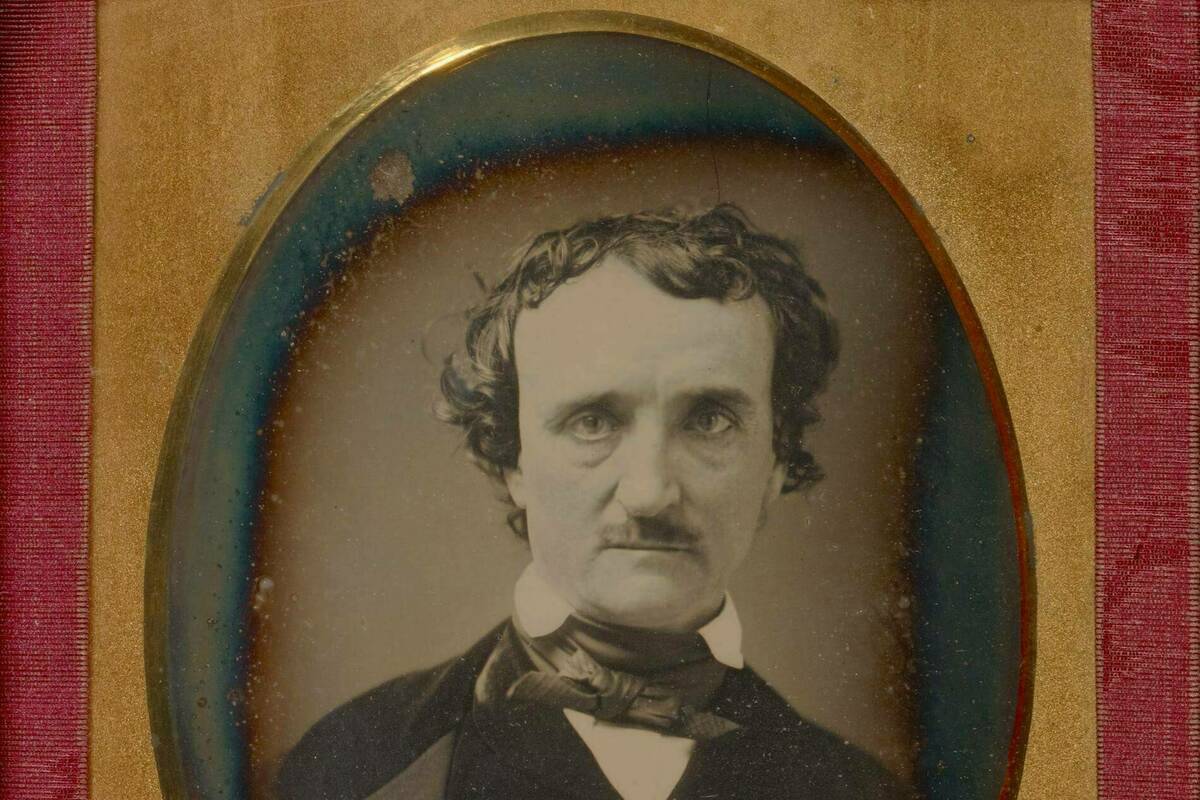

In his “Philosophy of Composition,” an essay written about the process of writing “The Raven,” Edgar Allan Poe famously claims that “the death . . . of a beautiful woman is the most poetical topic in the world.” He wrote these words in 1846, a year before his young wife, Virginia, died of tuberculosis and during the time she was struggling with her illness. Her symptoms first appeared four years earlier in 1842: Virginia began bleeding from her mouth while playing on the piano. Even though Poe was hopeful this first sign of disease was merely “a rupture of a blood-vessel,” his wife’s health declined rapidly. Blood-filled coughing, tiredness, swelling, weight loss, and fever plagued her for years. Poe related to a friend that fits of bleeding, like the one that first revealed Virginia’s disease, recurred often. The symptoms increased in frequency—and the terror they caused Poe—until the twenty-four-year-old woman died six years following that first bleeding episode.

Poe described experiencing his wife’s illness and death as “the greatest [evil] which can befall a man.” He wrote of the emotional upheaval he felt while witnessing his wife’s illness and demise: “Each time I felt all the agonies of her death—and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more dearly and clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity. But I am constitutionally sensitive—nervous in a very unusual degree. I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”[1] Poe was no stranger to the horrors of tuberculosis. His mother had died of the same disease when she was twenty-four years old and Poe only three, leaving him orphaned.[2] Likewise, his adoptive mother, Frances Allan, died when Poe was thirteen, again also of tuberculosis.

Even casual readers of Poe’s writings are likely to know that the writer struggled (rightly so) with how to handle grief and suffering, especially regarding the women he loved and who loved him. For Catholic readers of his work specifically, it may be of interest to consider that in 1846—the same year Poe uttered his famous quote about the death of a beautiful woman—Poe’s family moved to a small cottage within walking distance of St. John’s College, which we know today as Fordham University. According to Poe biographer, Arthur Hobson Quinn, “Poe found intellectual and spiritual companionship during his life at Fordham.”[3] He befriended the Jesuits on campus, including Fr. Edward Doucet, who became the college’s eighth president. In a history of Fordham, Raymond A. Schroth reveals that Poe would often imbibe “a glass of wine with the fathers” to “calm his nerves.”[4] Poe said of the Jesuits that they were “highly cultivated gentlemen and scholars.” “They smoked and drank and played cards,” he mused, “and never said a word about religion.”[5]

Despite this claim that they never talked about religion, scholars ought not dismiss that Poe found solace among the Jesuits as he slowly watched his wife die. I am not suggesting here that Poe considered conversion to the Catholic faith; rather, his seeking out of the faith during a period in the United States when anti-Catholic sentiment ruled the day matters when interpreting his writing. It bears mention here as well that Poe grew up in Baltimore, the site of the nation’s first diocese (1789) and first archdiocese (1808). If there were a city considered to be a haven for nineteenth-century US Catholics, Baltimore in the nineteenth century is probably the closest one could come to such identification. Thus, Poe’s time with the Jesuits was likely not the first time he encountered the Catholic faith: he would have recognized its particularities. His attraction to the faith, and those practicing it, set him apart from other thinkers and writers of his day.[6]

Moreover, I suggest that his befriending of the Jesuits during a time of immense suffering suggests that Poe had more than a passing academic interest in the Catholic Church. With this said, as a practicing Catholic literary scholar myself, I find William Mentzel Forrest’s well-known position that “since [Poe] was a romanticist . . . [the] formal religion that attracted Poe most naturally w[as] Catholic[ism]”[7] more triumphalist than rhetorically sensible. Because of his breadth of knowledge and natural curiosity, Poe’s writing is suffused with imagery from various backgrounds. Aesthetically pleasing romantic writers with whom he shared literary circles, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, infused myriad religions in their works, yet they are certainly more widely known for their use of Buddhism than Catholicism. Thus, Poe’s distinctive turn toward the Catholic Church’s symbols and themes to shape his writing is a choice that carries weight in the choosing itself.

A version of Poe’s 1845 poem “A Catholic Hymn” first appeared in an 1835 short story titled “Morella,” a work thought to be inspired by Venerable Mother Juliana Morell (1594–1653), a Catalan Dominican nun and the first woman to receive a university degree.[8] Poe revised and republished the poem in 1845, clarifying the Catholic origins of the previously untitled verse.[9] The revised text is as follows:

At morn — at noon — at twilight dim —

Maria! thou hast heard my hymn!

In joy and wo — in good and ill —

Mother of God, be with me still!

When the Hours flew brightly by,

And not a cloud obscured the sky,

My soul, lest it should truant be,

Thy grace did guide to thine and thee;

Now, when storms of Fate o’ercast

Darkly my Present and my Past,

Let my Future radiant shine

With sweet hopes of thee and thine!

Catholic readers will likely notice the reference to the Angelus Prayer, a devotion that is traditionally recited three times daily, at 6:00 a.m., noon, and 6:00 p.m., or in Poe’s language “Morn,” “noon,” and “twilight dim.” The prayer, beginning with the ringing of a bell, centers on the Annunciation, the moment when the Archangel Gabriel revealed to Mary that she would conceive and bear Jesus. Poe’s fascination with the spiritual sound and significance of bells is also located in his more famous 1849 poem “The Bells,” legendarily written during his time living next to Fordham and daily feeling the reverberations of the belltower announcing the times for the Angelus.[10] Purportedly, Poe felt the vibrations of the bells from his house, and it was often at these times, that he trekked to the gates of Fordham, looking for friendship, or what Catholics might in this instance dub looking for communion.[11]

Additionally, in this poem, the speaker cries out to Mary in times of “good” and “ill,” recognizing her not only as worthy of veneration but also as specifically answering the person’s “hymn,” or song or poem of praise. This moment seems as if it is a sharing of a private revelation. “Thou hast heard my hymn!” the poet verifies, begging that Mary’s presence continue to feel spiritually manifest in their life: “[B]e with me still!” the speaker intones. Mary has provided comfort specific to the speaker’s emotionally turbulent times. The speaker’s revelation seems to be taking the form of an interior locution, such as that experienced by St. Teresa of Ávila.[12]

In a guide she wrote to her Carmelite sisters, The Interior Castle (1588), St. Teresa describes her interpretation of these types of mystical revelations, writing, “A soul . . . experience[es] all the interior disturbances and tribulations . . . and all the aridity and darkness of the understanding. A single word of this kind—just a ‘Be not troubled’—is sufficient to calm it.” Poe’s “Catholic Hymn” does not provide readers with a specific new revelation for others, but we know the speaker’s “soul” has received a soothing message. The speaker ends the poem stating that although “storms of Fate” will inevitably shake the tranquility of life, the hope is for a “Future” that will be radiant “[w]ith sweet hopes of thee and thine!” Mary has provided hope to the speaker’s soul during “bright times,” and the interior locution the speaker has experienced provides hope during the difficult ones. As St. Teresa notes, “A ‘Be not troubled’” seems to prove sustaining enough, and the speaker’s exuberance over Mary’s response to prayer seems to be the driving purpose of this praising poem.

One can imagine that Poe found particular solace in a virginal female figure like Mary, a woman whose body never decays and dies, as his wife’s was while he was composing this poem, but rather is assumed into Heaven. While “the death of a beautiful woman” is a “poetical topic,” it is not one that offers peace, and, certainly, one would surmise, it would not have done so for this particular writer who experienced numerous losses of “beautiful” women in his life. Significantly, Poe emphasizes Mary’s power in this poem, referring to her in line four of “Catholic Hymn” as “Mother of God.” This title hails her as Theotokos (translated from the Greek as “Mother of God”). Recognizing Mary in this way is central to Catholic Marian theology, which distinguishes Mary’s maternal relationship with Jesus and her role in the Incarnation. As Theotokos, Mary is revered as a potent intercessor, capable of presenting the prayers and petitions of believers to her divine Son. Moreover, her maternal role, mirroring her care for Jesus during his earthly life, positions her as a source of spiritual solace and support, exactly as she is positioned in Poe’s hymn.

In reference to Mary as Theotokos, the Catechism puts it this way: “One whom she conceived as man by the Holy Spirit, who truly became her Son according to the flesh, was none other than the Father’s eternal Son, the second person of the Holy Trinity. Hence the Church confesses that Mary is truly ‘Mother of God’ (Theotokos)” (CCC §495). Mary provides a connection between the human and the divine that is embedded, or, shall I say, embodied, in Poe’s description of her. The poem’s speaker even worries that the soul might become “truant” and stray from whatever needed interlocution Mary provided it, much as a child might stray from school and the lessons provided therein. Mary therefore is depicted as a parent and teacher, maternal and wise.

When characterizing Mary’s private revelation, Poe reveals that, through praising Mary, his speaker is brought closer to Jesus. “Thy grace did guide to thine and thee,” he articulates in line eight, “thine” referencing her son. This concept of encountering Jesus through Mary’s intercession, foundational to Catholic theology, would have been seen as alarming to the predominantly Protestant nineteenth-century US reading populace—a fact Poe would have been aptly aware of and yet still did not shy away from elucidating. Indeed, his attention to theological detail, particularly regarding that line, can be seen in that it includes one of the most distinguishable linguistic changes he made from the 1835 text in the short story to its standalone revision. He had written previously that it was Mary’s “love” that “guided him from thine to thee.” In 1845, it is “grace.” To quote the Catechism again, “Grace is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature, and eternal life” (CCC §1996–97). In this 1845 revision, God is centered. God (divine) gave grace to Mary (human), so that she could lead the speaker closer to Jesus (divine and human). In this, Mary is the intermediary (or intercessor), and the speaker becomes closer to God through the “undeserved help” of grace, of which Mary is the conduit. As a result, we might read the poem as one of consecration to Mary. Her human “love” is not enough to soothe the speaker’s soul, but her “grace” through God is. Because the speaker knows devotion to Mary will lead back to God (and his son, Jesus), we arrive at the poem’s ending, envisioning a “future” where the speaker places all “sweet hopes” under Mary’s auspices, the very definition of Marian Consecration.

Before concluding my reading of this poem, I call your attention to the last two words of the text—“thee and thine!” Here, we have an inversion of those words from line eight (“thine and thee”), underscoring Poe’s theological understanding, and emphasis, of St. Louis de Montfort’s eighteenth-century “to Jesus through Mary” devotional practice. It is always about Mary and Jesus together, specifically about growing closer to Jesus through Mary (“thine and thee” and “thee and thine”). When speaking of an ideal “Total Consecration” to Mary, Montfort shares what sounds like a synopsis of this poem’s theme: “Blessed is the man who has given everything to Mary, who at all times and in all things trusts in her, and loses himself in her.” The speaker in Poe’s poem does just this, ending with an exclamatory “thine!” and an unusually hopeful and redemptive perspective from Poe.

This “Catholic Hymn” suggests Poe, at least for a time, found consolation in choosing to contemplate what devotion to Mary might entail, for himself and others who may be suffering. The poem is a prayer in and of itself and, by all accounts, was meant to be interpreted, and used by others, in this manner. Poe, ever attuned to language, symbol, and rhythm, would have been fully cognizant of the type of worshipful work he was crafting—and the type of work he was publishing for others to consume and use for their praise.

As mentioned at the beginning of this essay, Poe’s most famous poem, “The Raven,” was similarly published in 1845, only six months prior to his revision of “A Catholic Hymn.” That poem, set during a “bleak December” (the month Catholics celebrate the Incarnation), illustrates a young man struggling with the loss of his love, Lenore. The man veers from trying to find comfort in “a bust of Pallas” (a signifier of Classical learning and science) to a raven who visits him. The raven’s signification is less clear than the statue’s, but we know “fear” is one of the speaker’s first responses to the animal. Importantly, so is curiosity: “Let me see, then, what threat is, and this mystery explore— / Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore.” Pause, if you will, and read that last line once more. The narrator is asking for his heart to “still” so he can explore mystery. It feels very much as if the speaker is invoking an invitation to prayer; at the very least, he is opening himself up to some type of contemplative practice. Psalm 46:10 focuses on the power of stillness: “Be still, and know that I am God.” To contemplate, or to “explore” divine “mystery,” we must still our hearts before understanding can be reached.

Yet the narrator assumes his visitor is a “threat.” He seems terrified by the raven whose repetitive refrain, “Nevermore,” reminds him of his grief and loss. He will see his beloved “Nevermore.” “Is there—is there balm in Gilead?” he asks at one point of the raven, seeming to inquire whether there can be any comfort in the Christian story at all, any comfort in the mystery at its core. The phrase he utters references the Old Testament verse Jeremiah 8:22, in which Jeremiah laments the spiritual and moral decay of the people of Israel. The prophet uses the metaphor of a wound to describe their moral and spiritual condition, and he asks whether any remedy or healing is available, symbolized by the “balm in Gilead.” Jeremiah essentially expresses his concern that despite potential sources of healing and guidance, the people continue to suffer from their sinful ways and need spiritual restoration. In “The Raven,” the narrator refers to the bird as a “Prophet,” likening him to Jeremiah then and assuming from their first interaction that the bird is there to foretell only evil.

While Jeremiah does prophecy evil in the future, he offers hope to those who would believe and heed him attentively—yet no one does. Indeed, had the narrator of “The Raven” heeded the answers that the Bible provides about grief and suffering, it is possible he might have had a less stark reaction to the appearance of the bird “tapping” at his “chamber door.” Perhaps the narrator might have even remembered these words referencing ravens in the Old Testament book that most conspicuously contends with the “why” of human suffering, Job 38:41: “Who provides food for the raven when its young cry out to God and wander about for lack of food?” The answer to this question is, of course, God. God looks out for young and old ravens alike. Raven parents often travel long distances, seemingly abandoning their nests, in their quests to forage for food. When their parents are away, young ravens are known to wander away from the nests, often putting themselves in peril. In this verse from Job, God’s grace is there to aid the suffering ravens, both those who are trying to protect their young and the young themselves: the raven’s complex plight parallels Job’s immense suffering. Like the young ravens, Job has lost everything for no seeming reason. Like the raven parents, he cannot protect those whom he loves from suffering; his children, servants, and animals all perish in a storm. Most importantly, though, like all the ravens, old and young, Job needs to trust in God’s grace, or “undeserved help” as we learn from the Catechism. The only comfort that can be found, then, is unencumbered faith in God.

The narrator in “The Raven” cannot see beyond his own grief, and he projects “evil” onto the bird. While the narrator claims they both “adore” God, the raven simply repeats what is reflected by the human in front of him, a feeling of emptiness, of desolation, of “nevermore.” If “A Catholic Hymn” offers one of the only hopeful responses to grief and suffering that can be found in Poe’s oeuvre, we can read this poem as apophatic in its theological scope. Recall the buoyant ending of “A Catholic Hymn,” which focuses on “hope” and a “future” that is “radiant.” In contrast, here are the last two lines of “The Raven”: “And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor / Shall be lifted—nevermore!” The speaker in this case appears to go mad because of grief, his soul never lifted out of suffering. The poem is absent of hope, and it seems this loss is not because of the raven’s visit but because the speaker refuses to see the hope the raven could have provided him. The speaker, in essence, refuses to see God’s grace, and in this, readers might come to mourn his soul as well as that of his beloved Lenore.

Edgar Allan Poe died on October 7, 1849 under mysterious circumstances in Baltimore. It is unclear even why he was visiting the city. What we do know is that following his wife’s death, he, much like the narrator in “The Raven,” was increasingly unstable mentally, overwhelmed by the gravity of losing his beloved. Catholic readers likely also know that October 7th is the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary. On this day, we celebrate the power of Mary’s intercession through prayer, specifically through contemplating the “Joyful” and “Sorrowful” mysteries of our faith or, as Poe states in his hymn, the “joy and wo” and the “good and ill.” While these coinciding dates may be pure happenstance (and I suspect most think they are), I bring up the possibility that they may not be. As we contemplate Poe’s life and death, the mystery surrounding it, and our faith, I suggest that when we read Poe in the future—and perhaps even pray with his hymn—we remember his connection to the Blessed Mother, obscuring his Catholic imagination “nevermore.”

[1] Quoted in Arthur Hobson Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1941, 1997), xliii.

[2] Poe’s father had abandoned the family a year before his wife’s death.

[3] Ibid., 520.

[4] Schroth, Raymond A., S.J., Fordham: A History and Memoir, rev. ed. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 24.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For a strongly worded case that Edgar Allan Poe might have considered Catholic conversion, see Burduck, Michael L. “Usher’s ‘Forgotten Church’? Edgar Allan Poe and Nineteenth-Century American Catholicism” (Baltimore: Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, 2000).

[7] William Mentzel Forrest, Biblical Allusions in Poe (New York: Macmillan, 1928), 82.

[8] Benedict M. Ashley, The Dominicans (Eugene, Oregon, 2009), 158.

[9] Here is a link to the 1835 poem that appeared in “Morella” for comparison. Poe took out the first four lines in his 1845 revision and made other minor changes, including replacing the word “love” with “grace” in what is line 8 of the above text.

[10] The nineteenth-century university’s belltower is affectionately dubbed “Old Edgar Allan” today and is on display in Fordham’s library.

[11] Raymond A. Schroth, S.J., Fordham: A History and Memoir, rev. ed. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 24.

[12] An interior locution is a specific form of private revelation when a person believes they have received a message or communication from God within their inner self. This typically occurs through thoughts, feelings, or impressions. No apparition necessarily accompanies this type of revelation, only a message to soothe the soul in some way.