The experience of illness can be isolating and alienating. Serious and chronic illness can make one feel unwelcome in one’s own body and out of place in a world of otherwise healthy people. The theme of illness as alienation is explored in Susan Sontag’s 1978 essay “Illness as Metaphor.” Sontag, who at the time was undergoing treatment for breast cancer, compares illness to a second citizenship—one that we must all take up at some point in our lives:

Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

This image of illness as a second and inferior citizenship draws attention to how illness can place a barrier between the self and the world. Even with excellent medical care, one can still feel fundamentally alone and unsupported.

How might we ameliorate the exile of illness? Modern medicine has been spectacularly successful in providing treatments for some of the most aggressive and debilitating forms of disease. But many still struggle to cope with the existential dimensions of the experience of disease or injury.

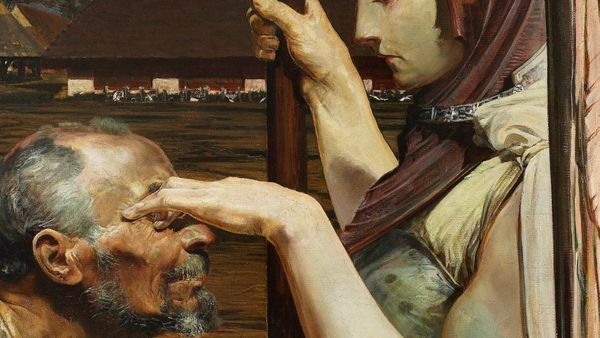

Hospitality—which can mean the literal reception of guests but has also been described as authentic human connection—is an undervalued remedy for the alienation of illness. A friendly conversation, a consoling touch, or even just a smile at an opportune moment, can cut deeper than any scalpel and heal more effectively than any salve. It reengages a person in the human world and establishes bonds of connection that are otherwise strained or severed by illness. We do well to consider how hospitality can be integrated into contemporary healthcare systems to ameliorate health-related existential suffering.

1. Illness and the Human Condition

Many diseases have a purely biological character. But the human person is a unity of body and soul. Illness is most properly predicated of the person qua a psychosomatic unity rather than just the body. Eric Cassell famously defined suffering as “the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person.” Serious illness undermines the unity of body and soul in such a way that the body ceases to cooperate with our desires and becomes hostile to our intentions, perhaps even the deepest of such intentions—the desire to survive and the desire for transcendence.

The phenomenology of illness is reflective of the human condition. Human beings are, according to Christian belief, in a state of exile. As a result of the Fall, our communion with God has been severed and a principle of disunity has been introduced into both our human nature and the natural world.

Indeed, human beings find themselves in a situation of existential alienation. As Augustine famously stated, “Our hearts are restless until they can find rest in you.” We have deep in our hearts a sense of having known and lost some infinite thing. The knowledge of the precise character of this “thing” eludes us, but this certainly does not numb the presence of that splinter in our mind drawing our attention to our original vocation. Our lives are permeated by a sense that we are not quite at home in this world.

The feeling of exile can be experienced in differing intensities throughout human life, but it is particularly tangible when we are sick. Indeed, it is striking how often illness is described as a phenomenon in which one experiences the body as a stranger or even an insurgent. New York Times Journalist Ross Douthat, for example, says this of the complications he experienced from Lyme disease:

The reality was pain that didn’t let you relax, let alone sleep; pain that made your body feel like a cage around your consciousness; tension, always tension, the opposite of a Victorian lady picturesquely swooning on a couch. All this was an education, an experience of what it meant to be an embodied human being that could be endured but not really explained to someone whose body was still a home, a cooperator, a friend.

Douthat’s vivid description captures in a disturbing but poetic manner how the body becomes an alien place for people with chronic pain. To return to the metaphor of exile, the body becomes a strange, inhospitable, and yet inescapable land in which the self is trapped. Whereas the soul has a desire for transcendence, warmth, and affection, the ailing body greets one only with coldness and derision—as if it were mocking our efforts to retain the intactness of our own lives.

2. Hospitality and Therapy

This description may make illness sound like a form of neurosis befitting of psychological therapy. There are branches of medicine, such as psycho-oncology, that provide this kind of support. But we also ought to focus on a therapy that is fundamental to human life: hospitality. Hospitality is today associated with the restaurant, hotel, and entertainment industries. A common thread throughout the concept’s history, however, is the idea of welcoming a guest—perhaps even a stranger—into one’s home. The ancient Greek epics of The Illiad and The Odyssey both give witness to the custom of xenia, or guest friendship, whereby one was obligated to welcome strangers into one’s home should they be in need of food and lodging.

This genealogy has led some theorists to define hospitality in terms of authentic human (and, indeed, spiritual) connection—welcoming someone into one’s heart, so to speak. This form of connection is not superficial or affected. It is characterized by what the philosopher Gabriel Marcel described as disponibilité (perhaps best translated as availability, though sometimes also translated as disposability). To be available, according to Marcel, means to be fully present to another person with all of one’s temporal, emotional, and spiritual resources. As Marcel wrote,

It will perhaps be made clearer if I say the person who is at my disposal is the one who is capable of being with me with the whole of himself when I am in need; while the one who is not at my disposal seems merely to offer me a temporary loan raised on his resources. For the one I am a presence; for the other I am an object.

Hospitality of this kind requires that one open oneself up fully to the other, and, indeed, offer a “gift of self.” Thus, Marcel writes, “to provide hospitality is truly to communicate something of oneself to the other.”

Hospitality, in this sense, is not just an analgesic for illness. An analgesic deals with the pain that someone is experiencing but does not address the underlying cause of illness. This is how hospitality is often (wrongly) conceptualized in contemporary healthcare. Hospitality is often characterized as an adjuvant or ancillary dimension of healthcare. The primary mode of treating illness is through drugs, surgery, and other medical interventions.

But hospitality is essential to medicine. It restores the intactness of the person by reuniting patients with others and the world. In reality, the deepest way in which we can be fractured within ourselves is by closing ourselves off from others or experiencing the effects of rejection by others. Hospitality addresses this effect of illness and reopens the self to the other and God.

Importantly, hospitality is not a completely foreign concept in healthcare. The earliest hospitals were all-purpose institutions that provided not only healthcare but also lodging and spiritual attention for travelers who were far from home. They were a place of welcome for strangers (hospes) who were in a foreign land. Hospitality is part of the DNA of Western medicine.

3. A Reintegration of Hospitality Into Healthcare

The principal form of hospitality in the provision of healthcare is chaplaincy services. Hospitals—both religious and secular—should ensure that adequate chaplaincy support is available for their patient populations. Roughly two-thirds of American hospitals have chaplains. But a significant minority of hospitals are without chaplaincy or pastoral support. It behooves healthcare providers to prioritize the recruitment and funding of chaplains and pastoral support for patients.

Healthcare practitioners themselves must not neglect hospitality. The physician-patient relationship cannot be confined to helping a patient cope with the biological effects of illness. A clinician must accompany the patient and offer their support, notwithstanding appropriate professional detachment and boundaries. We live in an age where many people do not identify with a religious tradition. Even those who do identify with a tradition may have a complex relationship with that tradition. As such, it increasingly falls to clinicians, rather than chaplains, to provide the existential accompaniment that chaplains otherwise would.

Clinicians may be skeptical about adding yet another task to their already burdensome professional load. Many clinicians are suffering from moral distress due to the strain that the pandemic has placed on healthcare systems. Hospitality may seem like yet another burdensome item on the medical checklist.

But hospitality is not another item to add to the list. On the contrary, it is an attitude and an ethos that permeates everything one does. Indeed, it seems that the biggest obstacle is not time or resources but rather a process of medical socialization that may have inadvertently led doctors to suppress their humanity and spirituality in the clinic. As Michael and Tracy Balboni have written,

Most clinicians are amazingly compassionate persons, but a separation of medicine from spiritual resources is now increasingly taking its toll on our social systems aimed to care for and heal the seriously ill.

The topic of spirituality and its relationship to medicine is a complex one, but it goes without saying that burnout in medicine has a strong existential and spiritual dimension, and encouraging clinicians to suppress their emotions and religious identities is probably not conducive to creating a more humane and hospitable healthcare system.

We should not ignore the effects of moral distress on clinicians. It is not easy to smile at a patient when you are sixteen hours into a shift and your ER is bed blocked. But if there is any consolation to the widespread experience of moral distress in contemporary healthcare, it may be the knowledge that a wounded healer is sometimes the most skilled clinician—one who knows not only the sickness of the body but also the afflictions of the soul.

Conclusion

Healthcare policy analysts may be skeptical about an increased focus on hospitality and, in particular, the prospect of increased funding for spiritual care training and programs. But this is not a question of funding as much as a paradigm shift in the way we think about medicine. Illness is not just an affliction of the body; therapy ought to account for the full existential effects of illness. We need to rethink the reductionistic approach to medicine that is implicit in many formulations of contemporary healthcare. We need to ensure that our healthcare system seeks to heal both the body and the soul.