For decades, many Catholics have lamented the slow drip of disaffiliation in the Church. There has been no shortage of polls and sociological studies which have analyzed the question of why Catholics leave the Church, and why especially so many young people move away from the faith of their parents.[1] While we agree with many commentators that the phenomena of disaffiliation and unaffiliation constitute urgent pastoral challenges, we will reframe these challenges with an eye to both history and theology. Our goal is to invite parents and other adults who have an impact in the lives of young people to discern how they might be part of a “stacked” approach to faith formation, with a nuanced understanding of its goals. Through the lens of this approach, we will offer some guidelines, rooted in our own experience of parenting and of working with young people in our professional lives, to cultivating a culture of religious discernment in the home.

Unaffiliation and Disaffiliation

Over the past thirty years, young people report increasing levels of religious unaffiliation. According to the General Social Survey, conducted for decades by the Public Religion Research Institute, there has been a more-or-less steady increase in the numbers of young people reporting that they are not affiliated with a religious congregation.[2] In 2020, over a third of young adults (18-29) reported not being affiliated with a religious congregation, a dramatic increase from the reported 10% in 1986.

The phenomenon of unaffiliation reflects a broader social trend across all age groups to report low confidence in institutions. Gallup polls since the 1970s have shown massive declines in Americans’ trust in big business, the medical system, the presidency, TV news, the US Congress, public schools, newspapers, and banks.[3] Similarly, there is a decline in trust in religious institutions, suggesting that young people display a general attitude of mistrust toward religious leaders and, by extension, religious communities in general.

More troubling, however, is the phenomenon of disaffiliation: the active choice to renounce one’s membership in a religious community. Whereas many young people who describe themselves as unaffiliated are simply unformed in any religious tradition, the disaffiliated are former members of parishes, schools, or other apostolates, who have left the community of faith for any number of reasons. According to the 2018 study Going, Going, Gone nearly 13% of young adults in the U.S. are former Catholics, and the average age of disaffiliation is 13 years old.[4]

The phenomena of unaffiliation and disaffiliation ought to encourage Catholic parents and religious educators to discern carefully what factors contribute to positive religious formation. These phenomena give rise to hard questions: how do we evangelize? Whom are we failing to reach? What might our community be doing to push young people away? What are we inviting young people to be part of? How might a mature Catholic faith help a young person to flourish?

These questions generate theological considerations. Why does God invite people to the community of faith, and how might the community of faith share that invitation with its younger members and nonmembers? We will return to this question later in this essay.

Digging Beneath the Data

Unaffiliation reached a high in 2016 and has shown some slight decline since then, suggesting that this phenomenon may have plateaued. It may also suggest that efforts at pre-evangelization and evangelization are reaching more young people, but that thesis remains speculative.

Unaffiliation is a very complex phenomenon. What a close look at the data reveals is that surveys themselves are blunt instruments: they do not offer a clear picture of what the key tasks of evangelization really are.

On one hand, over half of the young people who do affiliate with a religious tradition report little or no trust in religious institutions.[5] They might check the box “Catholic” on a survey, but have little meaningful engagement in the life of the Church. Moreover, what we know about the Catholic population broadly is that only a third of Catholics are regular Mass-goers, meaning that a clear majority of people who might check the “Catholic” box on a survey are really not in any meaningful, measurable way regular practitioners of their faith.[6]

On the other hand, many who are unaffiliated or disaffiliated show interest in deepening their faith. Over a fifth say that they attend a religious gathering monthly; over a quarter report trying to live out their religious beliefs in daily life; and over a third say that they are religious.[7]

What these observations mean for parents and religious educators is that it is important to develop a proactive, nuanced, and sustained approach to faith formation. Since young people are impacted by their peers, and since many young people move in and out of affiliating with a religious tradition, parents ought to expect that their children will need support and guidance. Religious education classes alone will not suffice.

Why Does God Invite People to the Community of Faith?

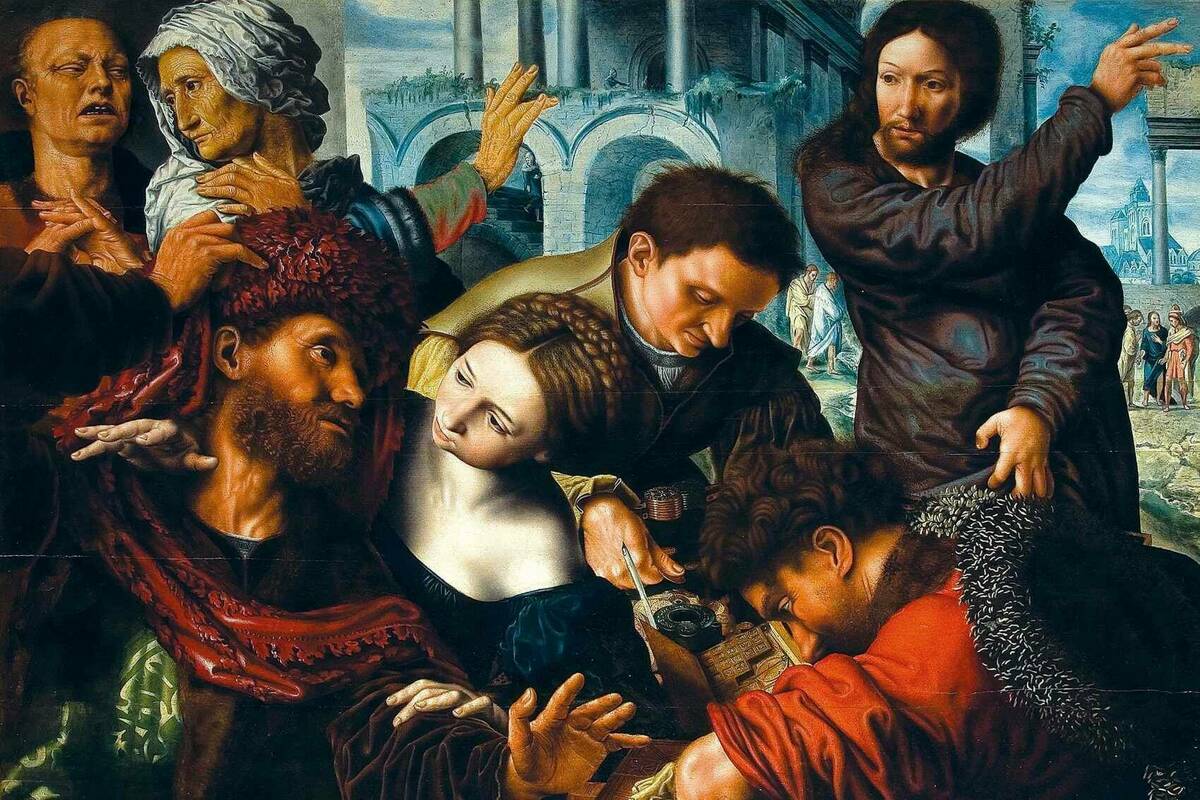

The phenomena of unaffiliation and disaffiliation give rise to ecclesiological considerations. First, let us note that even in the gospels we see people both drawn to Jesus and turned off by his message. Already in the apostolic period we see the beginnings of unaffiliation and disaffiliation.[8] At the core of the contemporary phenomenon of affiliation, we can see something of what Peter says in response to Jesus’s question about why the disciples stay, when others have left: “you have the words of eternal life!”[9]

We do not have much information about why early followers of Jesus joined the Church, how they practiced their faith, or what might have caused them to leave (or come back). We do know that some who were against the Church later joined it (like Paul), and that some who were members of the Church left it later (like Judas). Later writers such as Celsus and Julian show significant knowledge of the Christian tradition, but attack it sharply, pointing to the fact that they had been formed in the faith but later chose to leave it. Others, like Justin Martyr and Augustine, found themselves as young non-Christians to be drawn to the Church strongly enough to later become its vocal defenders.

These early stories of affiliation and disaffiliation point to an important theological point, namely that God does not coerce human beings into a life of faith.[10] Jesus’s method was engagement, with an eye to inciting attraction to his life and message, rather than pressure.

Perhaps the best gospel image for this kind of engagement is that of yeast, which Jesus uses to describe the kingdom of God. The kingdom, he says, is like yeast (or “leaven”) which is used to make bread rise.[11] Yeast is, to use a Greek term, katholikos (catholic), spread throughout the whole of the dough. It is not the entirety of the dough, but it impacts the entirety of the dough when it is kneaded.

Our thesis is that God invites people into the community of faith so that they might be the yeast which leavens the entirety of human society. One implication of this thesis is that God does not call all people to be members of the Church at all times—an implication which strikes us as obvious, since God has the power to do anything God wants with creatures, but chooses not to force their participation in the Church. God invites people to respond with their free will to participate in the Church’s ministry to the world, so that people might have “life to the full.”[12]

Another implication of this thesis is for parents and other members of families whose young people do not actively participate in the Church. While it is certainly good when a young person freely responds to God’s invitation to grow in holiness through participation in the liturgical life of the Church, it is not therefore bad when a young person refuses to participate in the Church’s liturgy.[13] This point will strike some as controversial, since participation in the Mass is one of the precepts of the Church.[14] However, we argue that the exigencies of contemporary development of a mature faith from adolescence to adulthood may well involve for many young people complex negotiation which a survey does not really capture. A growing faith may well involve periods of disaffiliation, or it may well involve a discerning navigation of a secular culture even in the period of nonaffiliation.

Stacked Faith Formation

Formation in Catholic faith is not always linear and systematic. While it is certainly true that the Church has seen periods in which populations are born, nurtured, and formed in its faith and traditions, that pattern can hardly be described as the norm, particularly if we are mindful of the massive explosion of Church growth in Africa and Asia. To be sure, the thick Catholic cultures of Europe, together with their iterations in the diaspora of the Americas and Australia, have a history of nurturing subcultures that have formed young people in faith through the process of socialization. Today, however, as these thick Catholic subcultures have lost influence, it is no longer sufficient to assume that young Catholics will appropriate a lived faith simply by being members of those subcultures. A new model is necessary.

We propose a model we describe as “stacked” rather than linear. The linear model involved several institutions that contributed to ongoing formation:

- Strong family structures

- Strong parish structures, including religious education/CCD

- Catholic schools

- Catholic Youth Organizations/sports

- Catholic high schools and colleges

- Catholic hospitals

- Catholic fraternal organizations

- Catholic cemeteries

These institutions ensured that it was possible to live out the entirety of one’s social life within the bosom of the Church. Young people could progress through these institutions, guided by trusted adults, especially parents and extended family, encountering developmentally appropriate influences to help them grow in their faith and their commitment to the Church.

Today, with the decline of many of these institutions, that linear approach is less common and less feasible for many populations. The stacked approach, by contrast, relies more on “modular” experiences which together contribute to formation in faith.

An analogy exists in the world of education. Today, adult students often are unable to move through secondary or higher education in a linear fashion, and so there has been a movement toward “stacked” diploma and degree programs, in which advisors evaluate various life and work experiences, together with more traditional classroom experiences, to measure progress toward completion. Stacking is about curating experiences and leading reflection on them in a way that moves a person toward growth and eventual mastery.

We believe that it is possible, and indeed an important opportunity, for parents and religious educators to curate a stacked model of religious formation for young people. Traditional religious education programs, though they have merit, often fall short of their intended purpose when children or adolescents who progress through them lack experience in sustained participation in the liturgical and social life of the Church. They may learn facts about the sacraments, for example, without any particular sense of why that knowledge means anything for how they should live. Parents may drop off children at a religious education class while they make a Starbucks run, seldom attending Mass or living faith meaningfully in the home.

A stacked approach, by contrast, would invite parents, families, and pastoral ministers to consider how they might work together to lead young people through various experiences that contribute to formation in faith. These experiences would include, for example,

- Arousing wonder (through exposing young children to art, music, dance, and other forms of expression)

- Practicing service (through guided experiences of love in action)

- Celebrating traditions (through sensory experiences appropriate to the times of the liturgical year)

- Learning prayer (as a personal, age-appropriate practice distinct from public worship)

- Cultivating discernment (by approaching difficult moral and personal questions through the wisdom of the Church)

- Encountering others (members of the local and universal faith community as well as people very different from them)

For parents, this stacked approach will mean relying less on formal religious education classes and more on developing relationships with other families who share the desire to form their children in faith. The home (oikos) can partner with the parish (paroikos, “next to the home”) to foster a host of stacked experiences for children at every developmental level. Less energy will be spent on finding teachers for a particular grade of religious education classes, and more energy will be spent inviting families to participate in positive, fun, formative experiences.

The Domestic Church as the Church

The phenomena of unaffiliation and disaffiliation are troubling and call for renewed pastoral energy. Parents who seek to form their children in faith will not, we have found, find great success by relying too heavily on the linear classroom model. The stacked model, by contrast, offers parents ways of approaching their domestic life with an eye to multiple goods: shared family activity; socialization with like-minded families; experiences that awaken and enliven their children’s faith.

These experiences, well curated through partnerships between parents and pastoral ministers, will themselves be experiences of Church for all participants. Undertaken in contexts where “two or three are gathered in my name,” they will contribute to both family and parish culture, and further will offer rich opportunities for relationships between families and parishes with very different backgrounds. The possibilities are endless.

Over time, we hope, expanded patterns of stacked formation will contribute to growth among young Catholics, as they discern the Church to be the place that affords them opportunities that answer the deep desires of their hearts for socialization, relationship-forming, discernment of meaning, sacramental encounter, deepening of faith, and commitment to living justly.

[1] See the work of Christian Smith and his colleagues, who have surveyed young adults for decades. A recent example is Christian Smith, Bridget Ritz, and Michael Rotolo, Religious Parenting: Transmitting Faith and Values in Contemporary America (Princeton, 2019).

[2] “The increase in proportion of religiously unaffiliated Americans has occurred across all age groups but has been most pronounced among young Americans. In 1986, only 10% of those ages 18–29 identified as religiously unaffiliated. In 2016, that number had increased to 38%, and declined slightly in 2020, to 36%.”

[3] Gallup, “Confidence in Institutions” poll, 2019, cited in Springtide Research Institute, “The State of Religion and Young People 2020: Relational Authority.”

[4] Robert J. McCarty and John M. Vitek, Going, Going, Gone: The Dynamics of Disaffiliation in Young Catholics (Saint Mary’s, 2018).

[5] Springtide Research Institute.

[6] Several surveys point to the statistic that about a third of Catholics attend Mass weekly, including Pew and Gallup.

[7] Springtide Research Institute.

[8] See, for example, John 6:60-66.

[9] John 6:68.

[10] See, for example, the Catechism of the Catholic Church 150: “Faith is first of all a personal adherence of man to God. At the same time, and inseparably, it is a free assent to the whole truth that God has revealed.” Cf. Dignitatis Humanae DH 10: "man's response to God by faith must be free, and... therefore nobody is to be forced to embrace the faith against his will. The act of faith is of its very nature a free act." See also the Code of Canon Law 748 § 2, “No one is ever permitted to coerce persons to embrace the Catholic faith against their conscience.”

[11] See Mt 13:33; Luke 13:21. I rely here on Walter Ong’s essay, “Leaven: A Parable for Catholic Higher Education" in America, 7 April 1990.

[12] John 10:10.

[13] By liturgy here we mean the word in its fullest sense: not only community worship (especially the Eucharist), but more broadly the “work of the people” by which God builds the kingdom on Earth.

[14] Catechism of the Catholic Church 2041–2043.