Christmas is both cosmic and terrestrial, when angels sing from empyrean regions to outcasts, and a baby is born where animals masticate and defecate. “Glory to God in the lowest!,” said G.K. Chesterton in the fifth of his Ariel Poems, aptly entitled “Gloria in Profundis.” The same could be said of most human births—as every new parent quickly comes to know, blood and feces paired with transcendental joy are the gifts offered to parents with every new child, at least to those with open arms and hearts to receive them.

But the low being invaded by the high has another, more central, connection to the mystery of Christmas. Human moral chaos not only conquered by, but fully drawn into, the perfect symmetry of salvation. The impenetrable mystery of human familial and socio-political wreckage reshaped and made beautiful by the One who descends into it—while also emerging from it: Jesus, the Savior.

This oft-forgotten, but much more essential, mystery of Christmas is celebrated by one of the most mathematically ingenious masterpieces human minds have ever conceived, the North Rose Window at Chartres Cathedral. Although Chartres also has a Jesse Tree among its lesser windows, the North Rose is its truest embodiment of Advent and the salvation history we celebrate in this holy season. To understand how symmetry and geometrical perfection overtake sinfulness within that work of art, we must turn our attention to seemingly the most mundane passage in all of the New Testament, the genealogy with which St. Matthew begins his Gospel.

This passage is read annually at the threshold of Christmas, on December 17, the beginning of the O Antiphons: “O Sapientia [O Wisdom].” This is exceedingly ironic, because the genealogy of Jesus is thoroughly saturated with non-wisdom, with foolishness and rashness provoked by lust, greed, and envy. To appreciate this, we must put some flesh and blood on the bare skeleton of that long list of names, an easy task because, as will be seen, it contains not only the prurience of flesh but also torrents of blood. Jesus’s genealogy is not like any that decent people hope to uncover when they buy a subscription to a genealogy website.

Certainly written with Jewish-Christians in mind, Jesus’s genealogy begins with Abraham. Unlike John, who begins his introduction to Jesus in the heights—”In the beginning was the Word,”—and unlike Luke, whose genealogy has a more universal scope, beginning with Adam, Matthew adopts a much more concise focus, examining only Jesus’s Abrahamic and Davidic heritage, where human misdeeds can be more thoroughly illustrated. He lists fourteen generations between Abraham and David, in whom Jesus’s family line became royal; then fourteen between David and the Exile, when Jesus’s family lost their power; and then fourteen until Jesus, the one who restores the kingship in a new way.

Genealogies are all about flesh and blood. From Abraham to David we learn a lot about flesh (sex), then from David to the Exile, we learn even more about blood (ruthless violence). I will skip the first set of fourteen generations to focus on the second set, the one that starts with David—for the former, I recommend the final chapter of Herbert McCabe’s God Matters, whose retelling is my chief inspiration for this narrative.[1]

David does a fine job of combining sins of flesh and sins of blood. We all know how he fell for Bathsheba, committed adultery and conceived a love child with her. Then he did something we expect to read about in our Apple iPhone news feed: he covered up his misdeed by murdering her husband (or rather, having him murdered by proxy). Their love child died, but then they had Solomon, the next in the line that led to Jesus and a real player, with 700 wives and 300 concubines. He also cherished wealth and power and international acclaim, and so set the stage for political tragedy in the next generation.

Solomon's son Rehoboam would lose most of his grandfather’s kingdom, the Northern tribes, through a revolt against his cruel and oppressive tactics. He badly misruled the kingdom he was left with and encouraged pagan cults and sacred male prostitutes. Rehoboam’s son, Abijah, was just as terrible as his father, although Abijah’s son and grandson, Asa and Jehoshaphat, managed to be upright rulers most of the time.

We associate murderous devotion to political power with King Herod, who had the innocents slaughtered because he heard a rumor about the birth of a king he thought was his replacement. But he would not have outdone the next in the line that leads to the child he was attempting to kill, Jehoram (or Joram as Matthew calls him), good king Jehoshaphat’s son. Jehoram loved power so much that he killed his six brothers plus some Israelite princes to secure the throne of David. He then tried to reunite the two kingdoms, Israel and Judah, by marrying Athaliah, the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel, the evil king of Israel and his notorious wife.

Matthew skips over the next two in the line, but they are worthy of mention. Jehoram’s son Ahaziah was a devotee of pagan gods; his mother Athaliah was his “counselor in evil” until he met his end by being executed in a revolt. Athaliah then decided that all of them must go, and began systematically murdering all of the princes of Judah (that is, her own grandchildren) so that she could rule. But one of them, Jehoash, was rescued from her and was hidden until he was old enough to rule. He would also forsake God and had a prophet stoned for rebuking him before being assassinated by his own servants. Jehoash’s son, Uzziah, was a well-meaning but impulsive king who ultimately contracted leprosy, like those that his great (multiplied by twenty) grandson Jesus would touch and heal in violation of the law of Moses.

Uzziah’s son is Jotham, but there is not much to say about him because his son, Ahaz, deposed him with the help of a pro-Assyria faction. For those who are keeping up, that is the Ahaz to whom the promise was made that “a virgin shall conceive and bear a son.” Ahaz had one of the greatest prophets of all time as his spiritual director, Isaiah, but he did not listen much. He embraced paganism, getting into the worship of the stars and setting up a pagan altar in the temple, and ultimately sacrificing his son to Moloch, the Canaanite deity.

His son Hezekiah is one of the rare good guys in the period between David and the Exile, but he was not much of an inspiration to his son, Manasseh, who reigned for 50 years and burned babies alive to Moloch, only repenting at the end of his life, an all-too-convenient deathbed conversion. Manasseh’s son Amon (Matthew calls him Amos) did the same. Amon’s son Josiah, a truly heroic figure, tried to reform things, but it was too late. Josiah became king when he was only eight, and before he turned 40 he was killed in battle by Egyptian archers. There was a long struggle for the kingship and his son, Jechoniah, only reigned for three months and ten days before the Babylonians swept in and destroyed Jerusalem and took him and the people off to Exile. God, it seemed, had had quite enough.

After the Exile things quiet down, partly because there are not any kings, but mainly because most of the names are not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible at all. As McCabe notes, for all we know Matthew invented some of them to bring their number up to fourteen—Luke mostly has different names in this period, until we get to Joseph, whom Matthew designates “a just man,” which definitely needed mentioning considering his ancestry.

And Jesus is the son of Joseph, not physically of course, as St. Matthew will tell us later. As McCabe also notes, “the Jews were not hung up on genetics—people could belong to one family, be brethren, without worrying about the exact biology of it all.” The Holy Spirit who gave the virgin her son is himself the creator of Joseph's genome (of every genome, for that matter) and could provide it in that great miracle. If children are first a gift of God and only second, a father’s offspring, then Jesus is Joseph's son through and through, he is truly the Son of David, a designation which he never disavowed when people addressed him as such.

And here we see the final woman in the genealogy which, quite unconventionally, mentions five women who have considerable theological importance (for more on this, see Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives). That woman is Mary, whose reference is changed to put the emphasis on her. She is not referred to as the wife of Joseph, he is referred to as the husband of Mary. Here is how Matthew puts it, “Jacob the father of Joseph, the husband of Mary. Of her was born Jesus who is called the Messiah.” In other words, “I am woman, hear me roar,” and we do hear her roar in her Magnificat recorded in Luke, where she says, “God has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly.” As we have seen, she was probably referring to her husband’s bloody ancestors when she said that part about “casting down,” but as we also know thanks to St. Matthew, she was probably thinking of her kind, quiet husband when she said that part about lifting up “the lowly.”

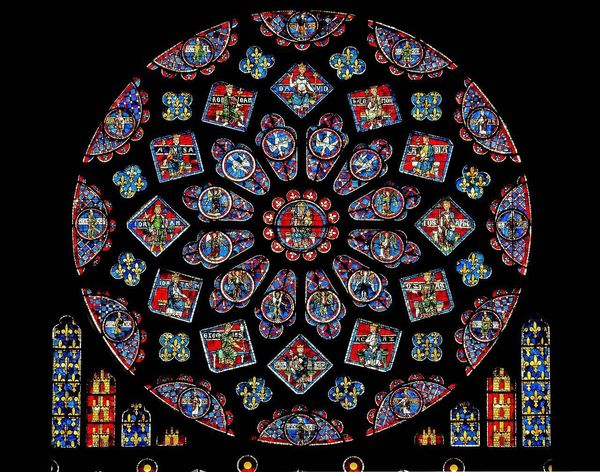

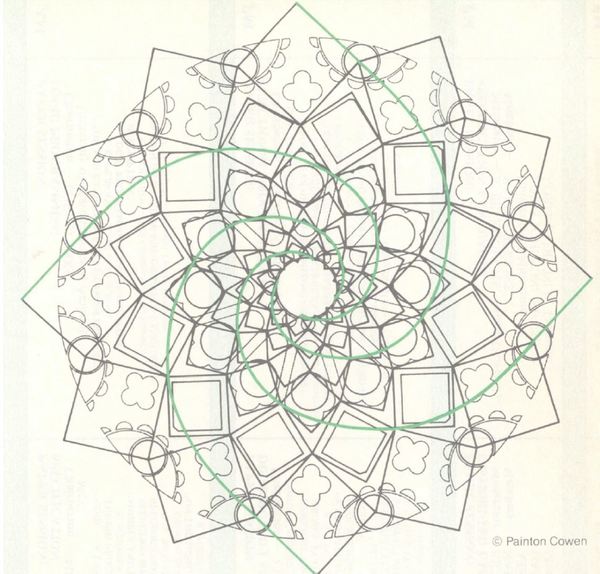

And that is what Matthew calls, “the Book of the Generation of Jesus Christ.” The point is too obvious to labor any longer: Jesus came from a family of homicidal maniacs, cheats, cowards, adulterers and liars, a real-life Game of Thrones. And this brings us to the North Rose of Chartres. There, at its center, the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Infant Jesus on her lap. She is surrounded by a circle of descending doves—the Holy Spirit—above her, and adoring angels below her. And then we meet 12 of the poor crooked people whose depravity I just finished narrating. David is at the top, then (considered clockwise, and non-chronologically) Solomon, Abijah, Josiah, Uzziah, Ahaz, Manasseh, Hezekiah, Jotham, Jehoram, Asa and Rehoboam, each robed in regal splendor, without a single indication of their misdeeds. And the sinful chaos of their lives is sublimated into an overlapping, threefold geometry that retains both the divine and the earthly in symmetrical relation to each other.

The window has repetitive sequences of twelve, the product of three (the Trinity) multiplied by four (the number of the elements: water, earth, fire and air). The doves and angels taken together that surround the circle with the virgin Mary and Child are twelve circles. Then, moving outward, come twelve of the Davidic kings. In them nature, specifically fallen human nature, is exemplified; their figures are not spheres but squares, whose four sides represent nature (the elements) more than grace, unlike the circles, which have perfect symmetry.

Then comes a ring of 12 fleurs de lis patterns, the symbol of the Annunciation. The fleurs de lis are contained within clover-like figures that have four circular lobes (nature) that meet at three points (Trinity): nature being newly reshaped by grace. Then, in 12 semicircles, we have twelve prophets, some of whom announced God's word to the often deaf ears of the kings. Here the top position is given to Isaiah, who is the prophet par excellence of the Incarnation.

But this is only what the eye can easily discern. In fact, there are three levels of the Rose Window’s geometry. The deepest level is based on the Fibonacci spiral, a series of ascending numbers which govern the growth of many flowers and plants, including pine coins, daisies, and of course, roses. The geometric rules that govern nature permeate the window; draw a spiral from the center of any of the prophets, and it will pass through the kings and angels, focusing on the Virgin at the center. There are twelve spirals to match the rings of twelve figures. Then another geometry integrates all of the figures within equilateral triangles, the three-sided figure representing the Trinity. Finally, a third geometry connects the prophetic semicircles to the squares defined by the triangles.[2]

All of this involves a much larger figure than the window; hence the prophets are in semi-circles, not full circles. The rest of the figure is only able to be reckoned mathematically; it is not visible. The mathematical message is this: God is outside of, greater than, the visible figure, all the while intimately present to it, causing it to become something beautiful. He is shaping history not through coercive action, but through his presence, through his word. The message of the genealogy, then, is that you cannot sink too low to be outside of God’s plan of salvation. For if these bandits, thieves, child killers and greedy potentates can be the path to salvation, what keeps you or I from receiving the mercy and saving grace of God?

Let us add to this the testimony of Luke’s Gospel: “But Mary said to the angel, ‘How can this be, since I do not know man?’ And the angel said to her in reply, ‘The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. Therefore the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God.’” The Holy Spirit is depicted here as hovering over Mary, just as, way back in Genesis 1, we are told that the Spirit of God swept over the waters at the moment of creation. Something new, something impossible to anticipate, is about to happen. Mary follows the very thrust of the universe, of creation, and takes it past where it ever went before her. Like the world God created, she is ready to leave behind the voids of the past and to open herself to the new and surprising, to God’s future, not her own. She opens up, and a new creation begins, a creation beyond death and destruction, of everlasting, imperishable life. She turns the darkness of her Son’s crooked lineage into the salvation of the world.

God writes straight with the crooked lines of human history—that is the mystery of the Incarnation portrayed in the message of the North Rose Window. To quote Chesterton once more, “Outrushing the fall of man / Is the height of the fall of God.” And that is perfect hope, hope for me and each and every person who calls on the name of Jesus, the Savior of the world. Jesus, son of Jehoram, son of Manasseh, but above all son of the Father and of Mary and Joseph, let the light of your Nativity shine upon us.