He was the good, not quite great, poet of a different America, an America that no longer exists. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was humane, not original like Whitman. He was original, but in his own lesser way. Famous on both sides of the Atlantic he met Queen Victoria and some even compared him to Tennyson in England. He is one of the handful Americans with Eliot and James honored in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey. His bust is placed next to the tomb of Chaucer. Yet, he was also revered by the common man. He was able to speak to ordinary American souls full of spiritual optimism, of the naïve hope that once possessed our ancestors. To read him is to read another America, an earlier America whose sins, of course, we know, but which we can, nonetheless, in some sense, regret is gone. Once a poet of America, now he is a ghost, his words remaining like ghosts do, somewhere in the metaphysical ether.

Forgive me my poetic talk, please, but I have thought on all these matters lately: on poets in general, and Longfellow in particular. He belonged to an America in which the lettered were still religious, unlike today when the literate and cultured do not know what to say about God or believers. “Life is real! Life is earnest! / And the grave is not its goal,” he wrote in a “Psalm of Life” (1839). Few poets write like that today (except maybe Christian Wiman), certainly not poets acclaimed, as Longfellow was, bards of America.

Thou, too, sail on, O Ship of State!

Sail on, O Union, strong and great!

Humanity with all its fears,

With all the hopes of future years,

Is hanging breathless on thy fate!

We know what Master laid thy keel,

What Workmen wrought thy ribs of steel,

Who made each mast, and sail, and rope,

What anvils rang, what hammers beat,

In what a forge and what a heat

Were shaped the anchors of thy hope!

“[S]ail on, O Ship of State!/ Sail on, O UNION, strong and great!/ Humanity with all its fears,/ With all the hopes of future years/…We know what Master laid thy keel,/ What Workmen wrought thy ribs of steel.” These words, from the long poem “The Building of the Ship,” at once spiritual and secular, written, like a plea, before the Civil War, brought Lincoln to tears, moved that such a man could move others like that, to talk like that about both soul and state.

But they are words that would not work today. Can we even imagine the sitting president weeping? Because that was a different America, an America of different souls, or at least as Alexis de Tocqueville would have called it, in an updated Democracy in America, an America of different manners.

In 1863 Longfellow wrote a poem called “Christmas Bells,” rendered ever since as a carol sung by just about everyone from the Mormon Tabernacle Choir to Elvis Presley. The best rendition, which you might want to check out, is the one by folk singer John Gorka. It is a beautiful poem. However, there is sadness in it, just under the surface. By this time in his life, Longfellow was a widower, having lost his wife tragically in a fire. The immediate occasion of the poem, though, the story goes, was his son, injured severely in the Civil War, fearing a long recovery, fearing too the end of America. Written on a Christmas particularly bleak, the poem is really a prayer, hope for something, a meditation on the bells of churches ringing in darkness:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Yet, “cannon thundered in the South,” he wrote. And “with the sound/ the carols drowned.” The bells marked an absence: the memory of peace, the longing for goodwill. The loss of his wife, his son’s injury, slavery, injustice, war, and America torn, it is a Christmas hymn of sadness, a poem written by a man at a loss for America:

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

It is sadness that speaks to many of us after the elections and in the midst of the pandemic; this early-American sadness was actually much like our own. Hate is strong and it mocks the song: peace on earth, goodwill to men. It is what I feel this Christmas, what I know others feel. An America divided, angry, and sad. Strong hatred and the mockery of innocence and of peace: these too much mar our country today. This is the case in our cities, our neighborhoods, our families, and African-American communities experience it disproportionately.

At least this much remains the same about America: that even if we do not recognize God as much as we used to, we recognize the despair, the bowed head of the poet wondering where peace went. Yes, I know it is nearly Christmas, and I wish you all a happy one. But I also want to be real, to be penitential, because it still is Advent. I do not want our Christmas cheer, at least here, to be cheaply merely sentiment. Which means we must acknowledge, feel it even, that it is just true that in our day hate is strong and mocks the song: peace on earth, goodwill to all.

But the thing is that the poet’s despair is not the end of the poem. And this is the point, the lesson I am unsure we are mature enough to learn. Because it would mean hearing bells again, hearing in them the hope they speak. As Longfellow believed, as he wrote at the end of his poem:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!”

This is the poetry of a sad man, but still who did not lose hope, who could not believe in the finality of despair because of the One in whom he believed. Because he heard the bells and could think on what they mean. But again, that was a different America, and ours is shrouded in a darkness sounded by fewer bells.

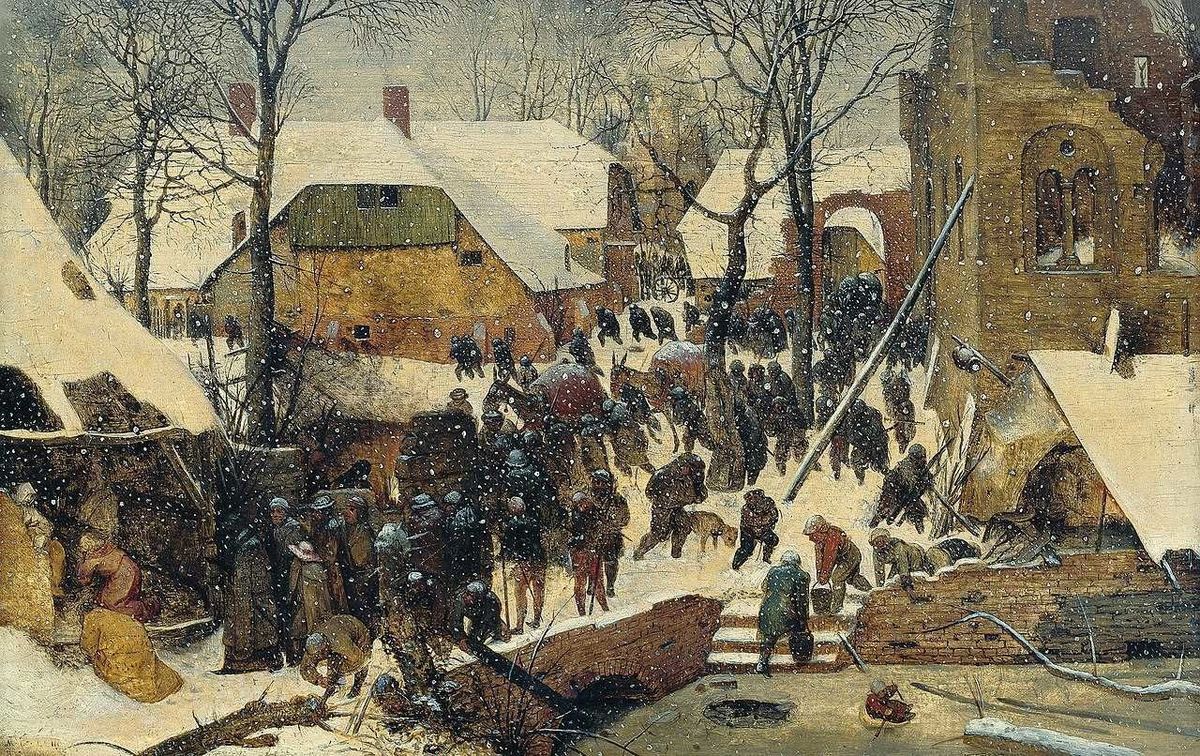

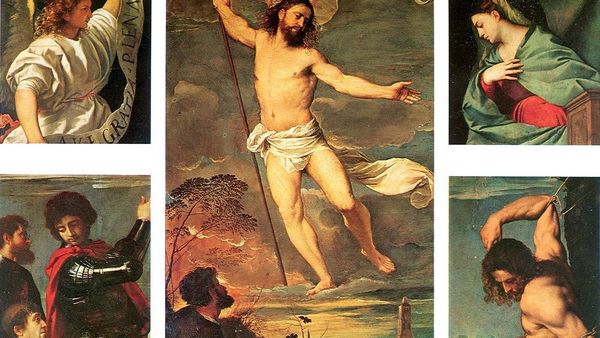

It is nearly Christmas, the feast of the advent of Christ. Remembering the story from the days of Caesar Augustus, of Joseph and Mary, of shepherds and angels in fields, of the child born for us, it is a feast by which we are meant to learn to hope. One advent to another, we are meant to learn how to live and wait for our “blessed hope, the appearance of the glory of the great God and of our savior Jesus Christ” (Titus 2:13). In the world, and first in our hearts, what Christmas means—what it can mean—is that although we walk in darkness, still we can see light (Isa 9:1). At least such is what our old stories show, what they are meant to mean.

But we must want to see; we must remember that we can see. In the fields buried in darkness, even the shepherds saw, angels appeared even to them. This is the image which, for me, brings it all together: “Glory to God in the highest,” the angels sang (Luke 2:14). It is the revelation of God repeated in all godly things, all beauty, mystical and ordinary, and in every act of hope. “I heard the bells on Christmas Day / Their old, familiar carols play,” the poet sadly writes. “Behold, I make all things new,” John, imprisoned, hears from heaven (Rev 21:5). This all is light breaking in, all of it Christmas. But to see it, we must want it, the faith that is light.

Because although dark, it is not gone: this feast and its God. Not gone, because some still hope, some pray. Because some of us still believe in an eternal God who becomes an infant. And because no matter how we fool ourselves, we are not all that different from poets and mystics and shepherds of the past. Because we are here: even the half-hearted, not just the faithful, remembering Christmas and ancient hopes that were, hoping such hope will show itself again. Like bells in the darkness, like angels in the field, and like the word of God silent in a manger.