How is it that a Church that deems itself able to develop doctrine does not end by corrupting it? It seemed evident to Gibbon and Francis Newman that the whole Catholic dogmatic system was just one doctrinal corruption after another, and their solution was to get rid of the whole thing. By comparison, Pusey and Döllinger believed that almost all Catholic doctrines were true. They believed that it was only in the nineteenth century that the (Roman) Catholic Church really began corrupting doctrine in a major way, even if the seeds of the Catholic Church’s demise had been sown in earlier centuries.

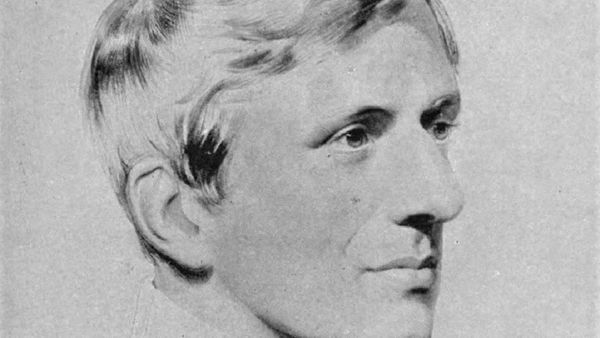

By 1845 and for the remainder of his life, John Henry Newman believed that the doctrines of the Catholic Church—about the Trinity, Christ, the Church, Mary, the seven sacraments, the papacy, purgatory, and so on—are faithful and ontologically true developments of the Gospel given by Jesus Christ and handed on by the Apostles. Ever since his death, however, some Catholics have interpreted Newman’s developmental theory along religiously liberal lines. In the introduction, I discussed the fact that for some Catholics today, Newman’s theory insists far too strongly on the ontological truth of all solemnly taught Catholic doctrine. But a significant number of Catholic theologians do what they can to claim Newman for religious liberalism. Some theologians, for example, find the needed leeway in his 1859 On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine, which they understand to teach the view that the laity can, by their lack of consent, nullify a solemnly taught Catholic doctrine—a view that Newman himself eventually explicitly repudiated, but not without first considering.

As noted above, against the emerging Ultramontanist movement, Newman made the point in On Consulting the Faithful that the doctrinal heritage of the Church is not solely enunciated by councils and popes but also is handed on in the Church “by liturgies, rites, ceremonies, and customs, by events, disputes, movements, and all those other phenomena which are comprised under the name of history.” Newman explains that it follows from this richer understanding of Tradition that “the body of the faithful is one of the witnesses to the fact of the tradition of revealed doctrine,” and indeed also that “their consensus through Christendom is the voice of the Infallible Church.”

On the one hand, Newman’s meaning is plain: among the “witnesses to Tradition,” along with councils and papal teachings, stands the “consensus” of the faithful. Not only the clergy but also the laity participates in the authoritative handing on of divine revelation. Thus, focusing on the people with power in the Church—popes and bishops—does not suffice for understanding what is meant by a living Tradition; indeed, a focus on power distorts the matter.

On the other hand, Newman’s concerns about doctrinal corruption are hardly set to the side here. Newman does not mean that when the consensus of the faithful becomes difficult to perceive—as for instance during the Reformation period, when a large portion of Catholics (led by the Reformers) rose up against many Catholic doctrines in the name of sola scriptura—the solution is to get rid of the contested doctrines, so that only doctrines most clearly supported by a supposed “consensus of the faithful” remain in place. Instead, Newman is aware that one has to ask who counts as “the faithful” and what it means to have faith.

Newman drew his Catholic understanding of the consensus fidelium from those theologians who sought to defend the truth of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception by appeal to centuries of devotion and liturgical practice. On this view, the consensus or sensus fidelium is “distinct (not separate) from the teaching of their pastors” and indeed mirrors it. The infallibility of the Church, under the Holy Spirit’s guidance, depends as much on the laity as on the powerful clergy, but the laity’s role does not mean that the laity of any particular era (or the clergy either) is empowered to overturn solemnly taught doctrine of prior eras.

Another issue that sometimes arises today with respect to doctrinal corruption comes from Newman’s 1877 “Preface to the Third Edition of The Via Media of the Anglican Church.” In this work, Newman addresses a variety of issues, but the pertinent one here is whether the sin of simony renders null and void all sacramental acts of a person who has been raised to the episcopacy or papacy by simony. The question is a significant one because some eminent theologians over the centuries have claimed that simony has this effect. If so, then given the extent of simony in the history of the Church, it would follow that valid apostolic succession in the Catholic Church has long ago come to an end. If the efficacy of the sacraments depended upon the purity of the ministers—as logic may sometimes seem to dictate—then the sacramental system would not last long.

Newman notes therefore that the Catholic Church has fittingly made judgments about such matters, not by application of theoretical principle, but by practical reflection or “generous expediency,” trusting in Christ’s promise to preserve his Church. In distinguishing the “Regal” from the “Prophetical” office of the Church, he observes for example that the papal acceptance of the validity of sectarian baptism was a minority position, rejected by various Synods and by Church Fathers including Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Cyprian, Athanasius, Basil the Great, Ambrose, and others. Newman concludes that “whatever is great refuses to be reduced to human rule [i.e., strict logic],” and so we must not be surprised to find the Church “presenting to us an admirable consistency and unity in word and deed, as her general characteristic, but crossed and discredited now and then by apparent anomalies which need, and which claim, of our hands an exercise of faith.”

Newman may be misunderstood here to be saying that sometimes—though rarely—there is in fact acceptable doctrinal corruption. In fact, he holds the opposite. As we saw above, his point is simply that it will not always be possible for either the theologian or the historian to tie up all loose ends. The theory of doctrinal development, in other words, is not another form of rationalism that answers to the fallen human desire to prove everything in matters of faith, as though faith were so uncomplicated as to allow for logical demonstration. In his fourteenth University Sermon, preached in 1841 when he was beginning to move toward his theory of doctrinal development, Newman bemoans rationalistic Christians who have “clear and decisive explanations always ready of the sacred mysteries of faith,” and who accept no divergence from their own private explanations. Such Christians have substituted the product of their own minds for the inexhaustible word of God—whereas dogmas not only provide light and truth, but also leave room for the “darkness” of divine mysteries that far exceed our finite capacity to understand.

The point is that for Newman, firm adherence to the dogmatic principle and to the intelligibility of the doctrinal development of the apostolic deposit of faith must be distinguished from dogmatism. Newman has no problem with the fact that doctrinal developments such as papal infallibility, while intelligibly grounded in Scripture and Tradition, do not have such logical force as to countermand absolutely every concern or problem. As Andrew Meszaros observes, the doctrinal development of the Church “shows its conditioning, its historical life, its meandering, searching, and reacting—its experimentation and its error.” Doctrinal development displays this historical life without thereby negating the “absolute and normative status” of the Church’s solemn doctrine. Historians may not be able to demonstrate with strict logic this or that element pertaining to doctrinal development, but, in the case of solemnly taught doctrines, historians (and theologians) will be able to make a reasonable case for the presence of a development rather than a corruption. A clear contradiction or rupture in solemn doctrine would be doctrinal corruption. Such a contradiction is perfectly imaginable: for instance, one could imagine that (were it not for the Holy Spirit’s guidance) the Catholic Church could eventually teach that confirmation’s status as a sacrament is uncertain, or that a valid and consummated sacramental marriage between two Catholics is not absolutely indissoluble, or even that Jesus did not rise bodily from the dead but instead “rose” in the hearts of the disciples. Such a rupture would make all Catholic dogmas to be fundamentally reversible under new circumstances—the very opposite of Newmanian doctrinal development.

When faced with the messiness of history, religious liberalism adopts the solution of identifying as “development” what could only be a chain of doctrinal corruptions, if indeed (as religious liberalism denies) there ever was a divinely revealed apostolic deposit to be corrupted. For religious liberalism, there is nothing but an ever-changing doctrinal expression of a universal religious experience grounded in Jesus. The other extreme is taken by religious traditionalism, which shies away from the often-messy historicity of doctrinal development, including the historical context of Jesus himself. For both religious liberals and religious traditionalists (as distinct from those who recognize the historicity of doctrine without falling into a historicist view of doctrine), Newman’s writings are suspect, even if occasionally useful.

As an example of religious traditionalism as Newman perceived it, one might mention Henry Manning’s 1861 remark (prior to succeeding Cardinal Wiseman, who died in 1865): “The one truth which has saved me is the Infallibility of the Vicar of Jesus Christ, as the only true and perfect form of the Infallibility of the Church, and therefore of all divine faith, unity, and obedience.” In fact, the infallibility of the pope hardly preserves Catholics from all difficulties, since, as history shows, not all the words of the pope are true or helpful. The pope has a significant role, but Manning exaggerates it. No doubt, a form of Ultramontanism can equally affect those who style themselves “progressives,” depending upon who holds the papal office.

Catholic religious liberalism has many adherents today, and its worldview is articulated well by Peter Hünermann as follows: “Those who believe and who affirm the eschatological truth of Christ are called to accept a radical openness, a theological ignorance, the radical impossibility of complete self-determination, the impossibility of turning history into a straight line.” In light of what he deems to be the post–Vatican II awareness of “ambiguity in the authority of the Catholic Church,” Hünermann insists upon “emphasizing the Spirit, and not the letter.” On this view, Newman’s denial of doctrinal corruption in the Catholic Church could only be the result of a lack of historical consciousness. Hünermann suggests that whatever “continuity” there may be in Catholic teaching will come about through an embrace of “radical openness” and “theological ignorance,” grounded upon the ever-new “Spirit” that moves the Church forward into the “eschatological truth of Christ.” One thing is certain: this is not Newmanian doctrinal development but instead is an embrace of doctrinal corruption that, when all is said and done, renders Christianity devoid of truth-content prior to the eschaton. Indeed, if we are being “radically open” and practicing “theological ignorance,” we cannot really know that there is a distinct divine “Holy Spirit,” let alone a real “eschatological truth of Christ.”

In John Henry Newman on Truth and Its Counterfeits, Reinhard Hütter provides an appropriate response to such perspectives. While recognizing the presence of significant change as part of the development of doctrine, Hütter criticizes those whom he terms “ecclesial presentists.” He sums up their perspective succinctly: “Ecclesial presentism holds the church to be a self-actuating and self-norming body empowered by the Spirit. Rupture is an inbuilt moment in this dynamic. It is the Spirit-granted liberation from a past that once was the self-actuation of what is now the church of the past.” Hütter offers an equally sharp criticism of religious traditionalism or “antiquarianism.”

Recall that in repudiating religious liberalism, Newman insisted that doctrinal development means that every “new truth which is promulgated, if it is to be called new, must be at least homogeneous, cognate, implicit, viewed relatively to the old truth.” At the same time, Newman was firmly associated with the “liberal” side of English Catholicism, at least by comparison with many of his fellow converts. The key to understanding Newman’s perspective both as an Anglican and as a Catholic, then, is to begin with his sense of the Church’s Spirit-guided mediation of divine revelation in Jesus Christ. Christopher Cimorelli observes, “One of the goals of the Oxford Movement was to ensure the church’s autonomy from the state, at the very least in doctrinal matters,” since the Tractarians perceived that the ongoing “pattern of secularization . . . was indicative of a failure to understand that God had entered history and revealed divine truths to humanity.” The Oxford Movement recognized that if one believes there is a God whose presence and action undergird all finite and historical realities (the “sacramental principle”), then the case for real continuity or identity-in-difference in the handing on of the apostolic deposit of faith (the “dogmatic principle”) becomes plausible—without the need for a reactionary or defensive response to historical research or natural science.

In this light, the significance of Newman’s early Oxford period becomes fully apparent with respect to his lifelong concern regarding doctrinal corruption. In the Apologia Pro Vita Sua, as we saw, Newman highlights two things that he learned from Joseph Butler and John Keble. The first was the doctrine of cumulative probabilities, and the second was the sacramental principle, the doctrine that “material phenomena are both the types and instruments of real things unseen.” The latter doctrine was confirmed for Newman through his reading of the early Alexandrian Fathers in the late 1820s. He remarks that their writings “were based on the mystical or sacramental principle and spoke of the various Economies or Dispensations of the Eternal. I understood them to mean that the exterior world, physical and historical, was but the outward manifestation of realities greater than itself.” In this way, the Church can be profoundly immersed in historical change, even while communicating unchanging divine realities in history.

Gibbon assumed that there is no God behind historical and natural phenomena, and therefore he interpreted all history as being about intraworldly power relationships. Gibbon deemed paganism to be good because it supposedly resulted in religious harmony and tolerance in the political sphere, whereas Judaism and Christianity fostered the political disorder of fanatical violence and persecution. Gibbon supposed that the proclamation of Jesus’ divinity diverged from the original teaching of the Jewish Jesus, and thus all Christian dogma is a corruption. By contrast, Newman began with the sacramental principle, which makes plausible a belief in divine revelation. Much more than Gibbon, he was aware of the violence and persecution built into the Roman Empire itself, but he did not reduce everything to politics. He viewed Athanasius as a defender of the truth of the Gospel, and contemporary biblical scholars have vindicated him by showing that the proclamation of Jesus’ divinity was present from the outset of Jewish Christianity.

Against Erastian threats to the integrity of the (Anglican) Church, Newman joined Froude in seeking to insist upon the limits of State power vis-à-vis the Church. Cimorelli points out that although “Froude . . . was more favorably disposed toward the revolutionary spirit” with respect to disestablishment, Newman and Keble were deeply influenced by Froude’s anti-Erastian arguments, since “the constitutional reforms of 1828–33 revealed the impossibility of maintaining the status quo, and called for something more than a mere conservative response.” This “something more” was a revival, in Anglican minds and hearts, of belief that the Church was founded by Jesus Christ and endowed with gifts that neither the State nor Church leaders have a right to alter or negate. In appealing to the patristic witness to the doctrinal and sacramental gifts given the Church, the Oxford Movement maintained that only a reaffirmation of such “Catholic” principles could preserve the Church from doctrinal corruption. As a Catholic, Newman retained this concern about the ways in which power can be abused within Christian communities, but now with a focus upon powerful clergy.

Francis Newman’s ideas are representative of the broad tendencies of the nineteenth century, even if the Victorian era was hardly as skeptical as scholars often imagine. Francis concluded that historical criticism of Scripture and of the Church’s dogmatic Tradition has demonstrated that both are false. In John’s view, the problem is that Francis’ understanding of the transmission of divine revelation in Scripture and Tradition was flimsy and misdirected from the outset. For John, Francis was bound to find doctrinal corruption where in fact there is doctrinal development.

Edward Pusey considered that he had good reason to suppose that the (Roman) Catholic Church in the nineteenth century was rushing headlong into doctrinal corruption. Newman, having shared Pusey’s views in the 1830s, ended up rejecting them. For Newman, attention to the teachings of the Church Fathers and Mary as the New Eve and Mother of God exhibits the plausibility of affirming that Catholic teachings about Mary are true developments, not corruptions.

Lastly, Döllinger insisted that the Catholic Church’s understandings of the papacy since the end of the patristic period have been a dreadful mistake, one that the Vatican Council turned into a flagrant doctrinal corruption. Against this perspective, Newman underscored that in the patristic period, the Church was able to speak with one voice across all nations and to define dogma in a universally binding way. The only Church with a plausible claim to do this now is the Church in communion with the bishop of Rome. This fact indicates the presence of a development: God always intended for the Petrine office to receive universal jurisdiction, so as to preserve the Church’s ability to function as a vibrant unity.

Did Newman’s effort to respond to the threat and challenge of doctrinal corruption succeed? My answer is, yes and no. Yes, insofar as Newman shows that Gibbon’s reading of the history of the early Church as a history of doctrinal corruption is no more objectively historical (indeed less so) than is the very opposite reading of the early Church as a history of doctrinal development. Yes, insofar as Newman shows that Francis Newman’s argument that rational inquiry necessitates skepticism about Christian doctrine is a false argument. Yes, insofar as Newman shows that an overemphasis on power, whether from the side of liberal Whig Anglicans or from the side of Ultramontanists, opens up the Church to the threat of doctrinal corruption. Yes, insofar as Newman shows that the dogmas of Mary’s Immaculate Conception and of the infallibility of the pope can reasonably be interpreted as doctrinal developments rather than doctrinal corruptions.

Yet, in another sense, the answer is no—at least in the eyes of the contemporary world. Newman understood this situation well. In a Catholic sermon, he asks what the “world” is likely to make of the notion that Mary is ever virgin and that she lives today as “the great Intercessor of the faithful.” The answer of course is that the world today is skeptical of such claims. Newman perceives that the “world” approves of Catholics when they hold their faith at arm’s length. The “world” tells itself reassuringly, “The Catholic doctrines are now mere badges of party. Catholics think for themselves and judge for themselves, just as we do.” In Catholicism that is assimilated to the “world,” the sacramental and dogmatic principles are downplayed or negated.

In his sermon, Newman concludes that the “world,” in encouraging doctrinal corruption, is the same world about which Christ says in the Gospel of John: “If the world hates you, be aware that it hated me before it hated you. If you belonged to the world, the world would love you as its own” (John 15:18–19). Newman therefore exhorts his hearers: “Be not seduced by this world’s sophistries and assumptions.” Instead, he urges his hearers to imitate and “follow the Saints, as they follow Christ.” Standing against the world’s “sophistries and assumptions” means recognizing that there is a living Creator and Redeemer God present and active in history. Of course, one law of the “world” is that humans make a mess of all institutions, generally sooner rather than later. The dogmatic principle thus expresses how radically Christ and the Holy Spirit are at work in the Church, which bears the liberating truth of the Gospel.

As Newman well understood, non-Catholics are unlikely to agree with Newman about the fidelity of Catholic doctrinal development. For instance, the Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart has recently described An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine as “Newman’s splendid speculative fantasia.” Hart suggests that the source of the “fantasia” is wishful thinking in the service of ecclesiastical conservatism. The problem with Newman’s approach to doctrinal development, Hart says, is that “he trained his gaze on only one horizon . . . the receding horizon of the past.” Hart considers that Newman overlooked the apocalyptic dimension of Christianity, in the light of which radical doctrinal ruptures can be justified. Going further, Hart deems that in reality, there is no doctrinal development of the kind Newman opposes to doctrinal corruption; there is a “continuous Christian tradition,” but not of the kind that Newman’s seven notes wish there might have been.

When one looks closely, however, Hart’s critique of Newman can be seen to arise from religious liberalism. For example, while praising “the wonderfully rich theological heritage of the council [of Nicaea],” Hart maintains that “the historical record gives no evidence for or against the correctness or incorrectness of any doctrinal synthesis,” and he concludes that the most that can be said is that the Nicene tradition is “handed over to future elaboration, adaptation, and reconceptualization.” In his own pushing beyond Newmanian doctrinal development, Karl Rahner said something similar. Along lines that resonate with Rahner’s essay “Yesterday’s History of Dogma and Theology for Tomorrow,” Hart continues, “It would be foolish, moreover, to suppose that one could foresee the forms it might yet assume, the accords it might yet strike, the discoveries it might yet make—both within and beyond itself.” Thus, everything that we think we know in faith (as received and handed on in tradition) might change. Hart bemoans the fact that traditionalists, following a Newmanian path, will inevitably exercise their “inhibiting influence” against “any healthy developments” by resisting “the living tradition’s often chaotic and disruptive vitality” as inaugurated by the interruptive apocalyptic prophet Jesus.

Somewhat like Newman in The Arians of the Fourth Century, but from a perspective shaped not by romanticism but by Loisy, Hart has some critical words to say about dogma. He observes that “Christian dogma has always had some quality of disappointment about it, some impulse to anger, some sense that a creed is a strange substitute for the presence of the Kingdom.” Indeed Hart goes on to say that Loisy was right: Jesus preached the kingdom but the Church arrived, in “its often almost comically corrupt and divisive form,” ever needing to be sustained by a defensive and fear-filled propositional orthodoxy whose function is to ward off the “shadows of doubt” fueled by the “history of defeated expectations.”

The solution that Hart proposes is a religiously liberal Christianity that retains the doctrine of eschatological hope and a confidence in the creative fruitfulness of the liberated tradents. On this view, Tradition is “the constant creative recollection of a promise whose fulfillment and ultimate meaning are yet to be unveiled. Tradition thus must be seen as history’s secret, redemptive rationale.” Hart cautions against smuggling Newmanian doctrinal continuity through the back door. He argues that healthy Tradition “is possible only so long as faith is able to descry a future apocalyptic horizon where the tradition’s ultimate meaning is to be found, and is able also to refuse any reduction of that final revelation to whatever formulations of belief happen to be available at any given stage of doctrinal development.” Such a “reduction” prior to the eschaton would assert the ontological truth and irreversibility of all the Church’s solemnly taught doctrines. Preempting such a stance, Hart argues that dogmatic “formulations of belief” are at best “dim prefigurations” that can point us toward the eschaton in which everything will become clear; prior to this end, every formulation is in principle open to rupture and reversal, so long as our trust in the doctrine of the Kingdom does not itself succumb to the solvent.

Rahner’s updating of Loisy’s apocalyptic religious liberalism—or, indeed, Loisy’s own updating of Newmanian development—is perfectly echoed by Hart’s conclusion:

If Christian tradition is a living thing, it is only as tradition—as a “handing over,” a passage through time, a transmission, the impartation of a gift that remains sealed, a giving always deferred toward a future not yet known—that the secret inner presence can be made manifest at all. And that gift must remain sealed until the very end. . . . Once that vital force has moved on to assume new living configurations, the attempt unnaturally to preserve earlier forms can achieve nothing but, at the very best, the perfumed repose of a cadaver bedizened by mortuary cosmetics. True fidelity to whatever is most original and most final in a tradition requires a positive desire for moments of dissolution just as much as for passages of recapitulation and refrain. . . . Even the act of reverently looking back through the past to the tradition’s origin is also an act of critique, a judgment on the past that need not be a kind one, as well as an implicit act of submission to a future verdict that might be equally unkind with regard to the present, and even submission to a final verdict in whose light all the forms the tradition encompasses can be understood as at best provisional intimations of something ineffable and inconceivable. The tradition’s life, it turns out, is an irrepressible apocalyptic ferment within, beckoning believers simultaneously back to an immemorial past and forward to an unimaginable future. The proper moral and spiritual attitude to tradition’s formal expressions, if all of this is correct, would not be a simple clinging to what has been received, but also a relinquishing, even at times of things that had once seemed most precious: Gelassenheit, to use Eckhart’s language, release.

Loisy could not have said it better. Yet I note that one of the first things that will be relinquished or released is belief in the apocalyptic future in any specifically Christian sense.

Ultimately, Hart is merely repackaging the familiar notion that there is a fundamental intuition or non-conceptualizable religious experience that is the real core of everything toward which Christians have been striving—the real meaning (if we could only speak it) of everything that the Church’s faltering words seek to express. On this view, Christianity in its essence is a non-expressible religious experience, and “faith is the will to let the past be reborn in the present as more than what until now had been known, and the will to let the present be shaped by a future yet to be revealed.” Yet, as always, the theologians proposing this view have dogmas to which they are wedded—in Hart’s case the universal salvation of humans and angels/demons. Hart elsewhere makes clear that anyone who does not believe in this dogma is (objectively speaking) a worshiper of an evil “god” and that any Church that denies this dogma is proclaiming not God but an idol. Liberal theologies are as enmeshed in absolute dogmatic truth as are any other theologies, but on different grounds.

As we have seen, Newman understood the religiously liberal vision and he deemed it to be unreal, lacking adequate connection to the Gospel. For to say that Jesus is Lord, that Jesus is the divine Son, that Jesus died for our sins, that Jesus rose from the dead, that the Holy Spirit is divine, that God is Trinity, that the Church is Christ’s Mystical Body, that the Eucharist is Christ’s Body and Blood, that faith and Baptism unite us to Christ, that Mary is Theotokos, and so on, is not merely to profess “provisional intimations of something ineffable and inconceivable,” let alone merely to profess “precious” things that Christians should be prepared to “release” or that may be radically revised. Newman knew well that these truths are inadequate expressions of inexhaustible mysteries, while at the same time being ontologically true in their reference to realities. In this light, Newmanian doctrinal development is not a mere cover for “a radical diffuseness and pliancy native to Christian belief from its inception.” There exists an intelligible divine revelation, an apostolic deposit of faith. It can be and has been “developed” rather than “corrupted.”

Recall that the Newmanian theory of development of doctrine does not demand a rationalistic proof from history, but only accumulated probabilities. Hart exaggerates when he says that “as an object of historical scrutiny . . . tradition has all the appearances of a chance emergence from material forces, determined more by the power of natural selection than by any intrinsic rational necessity.” But Newmanian doctrinal development accepts that the path of doctrinal development is not determined by an “intrinsic rational necessity” but instead relies upon the providential course of the Spirit-guided Church in history.

From Hart’s perspective, sharing Newman’s concern about doctrinal corruption entails a defensive attitude, in which one looks out upon other Christians from a stance of “We’ve got it, they’ve lost it” and in which one embodies an absurd (and ugly) “overweening confidence” in one’s own orthodoxy and a corresponding confidence that “other communions have distorted or occluded or betrayed” the true orthodoxy. Let me close, then, by differentiating Newman on doctrinal corruption from such entailments of dogmatism. Newman does believe that Christ has given a revelation that is truly known and believed in the Catholic Church. He thinks that doctrinal controversy between Christian communions is possible on the ground of truth and he engages in such controversy. But, given the inexhaustible character of the dogmatic mysteries and the ease with which sin creeps into the human breast, he does not think that the truth of Catholic faith and sacraments warrants a sense of superiority on the part of Catholic believers. On the contrary, maturity in faith bears with it an ever-increasing humility and a corresponding reliance upon the divine mercy, not only for oneself but also for others. As Newman has the dying Gerontius say in “The Dream of Gerontius” (1853), “Lover of souls! great God! I look to Thee / . . . Help, loving Lord! Thou my sole Refuge, Thou.”

Far from trusting in his own advantages, whether intellectual or ecclesiastical, the mature Newman recognizes that all human boasting falls flat: “Opinions change, conclusions are feeble, inquiries run their course, reason stops short.” He perceives, in other words, that a dogmatic faith differs from dogmatism. The Church’s solemn doctrines are true and their corruption would be a terrible thing for all humankind. But this does not mean that Newman arrogantly imagines himself or other Catholics to be the apogee of divine wisdom in a world filled with lesser men and women. He is always open to seeing further and more profoundly thanks to the insights of others who disagree with him. Yet he holds, as a Catholic believer, to what he has received “concerning the word of life” (1 John 1:1). For Newman, it is the incarnate Lord, known in the Church’s liturgy, in prayer, and in the midst of our lives through faith and charity, who is the ground of our apocalyptic hope. To know this Jesus requires a faith shaped by repentance, humility, mercy, and love—a dogmatic faith, but not an arrogant dogmatism.

In sum, not least in his lifelong reflection on doctrinal corruption in light of Christ’s promises to his Bride the Church, Newman recalls us to the need to devote ourselves in faith and love to the one “head of the church” (Eph 5:23), Jesus Christ. As Newman asks his fellow theologians:

What will it avail us then, to have devised some subtle argument, or to have led some brilliant attack, or to have mapped out the field of history, or to have numbered and sorted the weapons of controversy, and to have the homage of friends and the respect of the world for our successes—what will it avail to have had a position, to have followed out a work, to have re-animated an idea, to have made a cause to triumph, if after all we have not the light of faith to guide us on from this world to the next?

Faith in Christ through the Spirit’s illuminating work, and not anything merely our own, is the great thing. The true sorrow of doctrinal corruption consists in its undermining our ability to relate to Jesus Christ in the full and rich way to which he calls us, which involves not pride in our own knowledge but rather cruciform humility, through which the Church manifests the love of the crucified Christ for the world. As Jude exhorted an earlier generation of Christians: “Now to him who is able to keep you from falling, and to make you stand without blemish in the presence of his glory with rejoicing, to the only God our Savior, through Jesus Christ our Lord, be glory, majesty, power, and authority, before all time and now and forever. Amen” (Jude 1:24–25).

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from Newman on Doctrinal Corruption (347–370) with the kind permission of Word on Fire Academic, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.