Over the last week or so, Church Life has published a series of reviews on the Best Picture Nominees for the Oscars. You can read our reviewers' takes on Lion, La La Land, Arrival, Hidden Figures, Fences, and Manchester by the Sea with the rest to follow over the coming days (thanks to Carolyn Pirtle's untiring work on these reviews).

Our yearly reviews of the Oscars always makes us think about the role of the arts in Catholic life. And in our editorial meetings, we often come to the conclusion that there does seem to be a divorce between the arts and Catholic practice, which is deleterious to the life of the Church.

New compositions in liturgical music tend to be more focused upon rallying the community around a specific series of beliefs of the composer (whose own musical training is lacking), often inattentive to artistic excellence. Churches and shopping malls continue to have more commonalities than differences, treated simply as gathering spaces in which beige walls and beige carpet cover over the sacred action of the Eucharist.

The arts seem only tangential to the liturgical prayer of the Church, a travesty of the first order, when considering the history of the Church. Nonetheless, at least the sacred arts have some presence within the Catholic imagination in the current age. It's hard to go to Mass and divorce oneself from the arts entirely.

But, it is far more rare to encounter a public artist of any sort, who brings their Catholic faith into the public sphere. When they do, such as Martin Scorcese's film Silence, Catholic groups offer critiques aplenty since the film does not conform to what said group imagines as Orthodox Catholicism. Such groups tend to desire not aesthetic excellence but a thin veneer of artistry covering over a safe narrative, which solidifies identity rather than raising questions about the nature of Christian existence in later modernity. This approach to the arts raises to mind something that Flannery O'Connor wrote about the response of too many Catholics to fiction:

If we intend to encourage Catholic fiction writers, we must convince those coming along that the Church does not restrict their freedom to be artists but insures it...and to convince them of this requires, perhaps more than anything else, a body of Catholic readers who are equipped to recognize something in fiction besides passages they consider obscene. It is popular to suppose that anyone who can read the telephone book can read a short story or a novel, and it more than usual to find the attitude among Catholics that since we possess the truth in the Church, we can use this truth directly as an instrument of judgment on any discipline at any time without regard for the nature of that discipline itself. Catholic readers are constantly being offended and scandalized by novels that they don't have the fundamental equipment to read in the first place, and often these are works that are permeated with a Christian spirit (Mystery and Manners, 151).

If Catholics are to encounter the arts, then they don't simply need an education into Catholic theological thought; they need a formation into the arts themselves. They need to discern standards of excellence found both in theological thought and the arts themselves. The arts and theology need one another.

It is for this reason that Catholicism's departure from the arts in particular is alarming. As Dana Gioia has argued in First Things, a divorce between Catholicism and the arts is detrimental for two reasons. First, contemporary art can easily slip into meaninglessness, no longer involved in seeking the transcendent. As Gioia writes:

Once you remove the religious as one of the possible modes of art, once you separate culture from the long-established traditions and disciplines of spirituality, you don’t remove the spiritual hungers of either artists or audience. You satisfy them more crudely with the vague, the pretentious, and the sentimental.

What is left are a series of cliches for describing the nature of the spiritual life. A general religious presence is enough, no longer attached to the spiritual disciplines that made this vision possible for artists like Thomas Merton or Flannery O'Connor.

In this sense, the Church must once again enter into the formation of artists. Academies and schools must open that bring artists into the theological and spiritual practices of the Church. Catholic schools, rather than kowtowing to STEM curricula that reduce human knowing to what can be turned into technology, should instead immerse every student into the arts. Conferences that involve Catholic artists themselves in these conversations, like the one taking place at Notre Dame this summer (Trying to Say God), are essential to renewing a Catholic vision of the arts.

My own University, Notre Dame, has reduced this formation into a single core course in an "aesthetic experience," ranging from literature to a course in film. This is dead wrong (and not just because aesthetic experience is a part of the human condition that should inspire all knowing not just the arts--there is and should be an aesthetic experience involved in mathematics as Bernard Lonergan would argue).

Students at a liberal arts institution in particular should be formed at least as consumers of the arts, whether they're studying as an engineer or as a doctor. For in the arts, especially those emerging from religious traditions, we encounter the great questions of meaning that should drive the human condition, to ennoble a truly liberal education.

Yet, Gioia speaks about an equally serious problem. When the arts and religion are divorced from one another, then the Catholic sacramental imagination enshrined in catechesis and liturgy suffers. The beauty at the heart of Catholic existence is neutered through the ideology of poorly-formed artists. Again, he writes:

Nowhere is Catholicism’s artistic decline more painfully evident than in its newer churches—the graceless architecture, the formulaic painting, the banal sculpture, the ill-conceived and poorly performed music, and the cliché-ridden and shallow homilies. Saddest of all, even the liturgy is as often pedestrian as seraphic. Vatican II’s legitimate impulse to make the Church and its liturgy more modern and accessible was implemented mostly by clergy with no training in the arts. These eager, well-intentioned reformers not only lacked artistic judgment; they also lacked a respectful understanding of art itself, sacred or secular. They saw words, music, images, and architecture as functional entities whose role was mostly intellectual and rational. The problem is that art is not primarily conceptual or rational. Art is holistic and incarnate—simultaneously addressing the intellect, emotions, imagination, physical senses, and memory without dividing them. Two songs may make identical statements in conceptual terms, but one of them pierces your soul with its beauty while the other bores you into catalepsy. In art, good intentions matter not at all. Both the impact and the meaning of art are embodied in the execution. Beauty is either incarnate, or it remains an intangible abstraction.

In this sense, the Church needs the arts if she is to proclaim the truth, beauty, and goodness of God in a secular age. Mystery attracts and woos. Yet, much of the Church's artistic treasury in the present is centered on the communication of information. Hymns don't lead one to contemplate the mystery of divine love as much as they function as rally songs that express the view of the composer. The Catholic sacred arts should lead to the worshipper to an encounter with the living God. Yet, often enough, they function more as a way of praising this community, this particular group of people: "Blessed are we, therefore, O God, you should feel blessed." Priests and religious have no training the arts, and therefore, make bad decision after bad decision relative to divine worship.

What then should the arts do in the context of worship, as well as outside of it, in Catholicism? Might I suggest that the Catholic arts function best when they operate out of a two-fold desire for mystery and encounter. That is, the Catholic artist does not reveal everything to the one who encounters the piece of art. Something is demanded of the person, a form of contemplative vision that is not reducible to looking at an ad in a magazine or reading a technical article. We must learn to see adequately.

At the same time, through the contemplative moment, the person encounters in the art the Word made flesh. For this reason, the artist must increasingly become competent in the narrative of salvation, the poetic and archetypal images that ground the Christian experience. Artists must look to the past canon, not because it is old, but because it incarnates something of this possibility for encounter in the present. It provides a series of spiritual disciplines, a memory of salvation, that no artist can simply pass over because he or she is "modern" or "up-to-date."

Two examples may suffice. First, much Eucharistic hymnody fails in the Church as art, because it erases both mystery and encounter. The text treats the Eucharist simply as an object to eat and to drink, avoiding the movement of the worshipper into an encounter with the Bridegroom, the Word made flesh. We can schlep to the front and receive, because the music itself, seems to perform this very act of schlepping. Schlepping leads to schlepping.

This Sunday, I went to Mass at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Notre Dame. There, we received the Body and Blood of Christ to the haunting melody of Peter Philips' Ave Verum Corpus.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6C1YeN9zlcQ

The text, of course, is a medieval one, sung during the consecration of the Host. In English, it reads:

Hail, true Body, born

of the Virgin Mary,

having truly suffered, sacrificed

on the cross for mankind,

from whose pierced side

water and blood flowed:

Be for us a foretaste [of the Heavenly banquet]

in the trial of death!O sweet Jesus, O holy Jesus,

O Jesus, son of Mary,

have mercy on me. Amen.

The text is itself an encounter with mystery, as the listener meets the verum corpus (the true body) of our Lord, born of the Virgin, suffered and died, in this heavenly banquet of the Mass. The past becomes present, unveiled as the piece is performed. It concludes with an act of devotion made possible by the artistry of the piece itself.

But, the music is truly divine. It enables an encounter with the mystery of the Eucharist, a slow unveiling of divine love, that brings the worshipper to his or her knees in adoration. Such a piece could not be written if the artist did not have an acquaintance with the textual and musical tradition, a spiritual life (in this case as a priest), and a sense that this piece is intended to lead the worshipper to Eucharistic contemplation. Not all is revealed in the text. Not all is revealed in the music. It is not a rally song about the virtues of the assembly, moving us toward action in a world before we have received the gift of love itself.

Rather, the worshipper is given a space to "name God" in the quiet contemplation of Eucharistic reception. There is a freedom to this piece, which is not present to the Eucharistic assembly that sings many contemporary hymns.

This kind of poetic encounter need not focus simply upon medieval texts reserved for worship. Flannery O'Connor's own sacramental vision suffuses her writing. She is often perceived as the most blunt of artists. But this is because there is a failure to read O'Connor beyond the literal sense of the text. Violence in a O'Connor short story, invites the reader to deeper contemplation akin to the way that a puzzle in the Scriptures necessitated a new form of reading for the medieval monk. One must pierce through the letter to the spirit.

O'Connor's "A Temple of the Holy Ghost," has all the characters that you'd expect from one of her short stories. It has a carnival, and the narration of a possible genital revelation performed by a hermaphrodite (of course, you never actually get to see the event yourself, part of the hiddenness of O'Connor's prose). It has mean kids, ditzy Baptists, big and pleasant nuns, and the singing of Tantum Ergo not once but twice. What is the reader supposed to do with this text?

In some ways, "A Temple of the Holy Ghost" is the perfect O'Connor story, because it manifests her method of both mystery and encounter as the text concludes. She writes:

On the way home she and her mother sat in the back and Alonzo drove by himself in the front. The child observed three rolls of fat in the back of his neck and noted that his ears were pointed almost like a pig's. Her mother, making conversation, asked him if he had gone to the fair...Her mother let the conversation drop and the child's round face was lost in thought. She turned it toward the window and looked out over a stretch of pasture land that rose and fell with a gathering greenness until it touched the dark woods. The sun was a huge red ball like an elevated Host drenched in blood and when it sank out of sight, it left a line in the sky like a red clay road hanging over the trees ("A Temple of the Holy Ghost," 248).

The fat of Alonzo, his misshapen ears, is part of the earthiness of the entire story. Whereas the little girl once mocked this, she can now pierce through the "ugliness" of Alonzo, because of her own Eucharistic worship. But, this worship is not something that remains trapped in the abbey church. Instead, it becomes an occasion to see the entirety of the created order, every last damn ugly bit, transfigured in Eucharistic love.

O'Connor never says this. She invites you, instead, to see this in every one of her stories.

So does the Church need the arts?

If the Church is to contemplate the gift of salvation revealed in Christ, a salvation that has transfigured every dimension of what it means to be human.

If the Church is also to bring this full humanity into encounter with the living God, who still is mediated through the sacramental life of the Church.

Then, yes, the Church needs the arts. The arts need the Church.

And if the Church really wants to evangelize in the coming years, we'll stop simply putting money behind small groups for discipleship, for passing out mediocre spiritual literature (because it is inexpensive), of building bland churches that are great for meeting but bad for beauty, and do something about creating an artistic culture in the present.

An artistic culture that is intended both for sacred worship, as well as the humanizing of every dimension of Christian existence. It will involve polyphony and bluegrass and icon-writing and architecture and the book-arts and everything.

That would be a New Evangelization.

A New Evangelization of mystery and encounter.

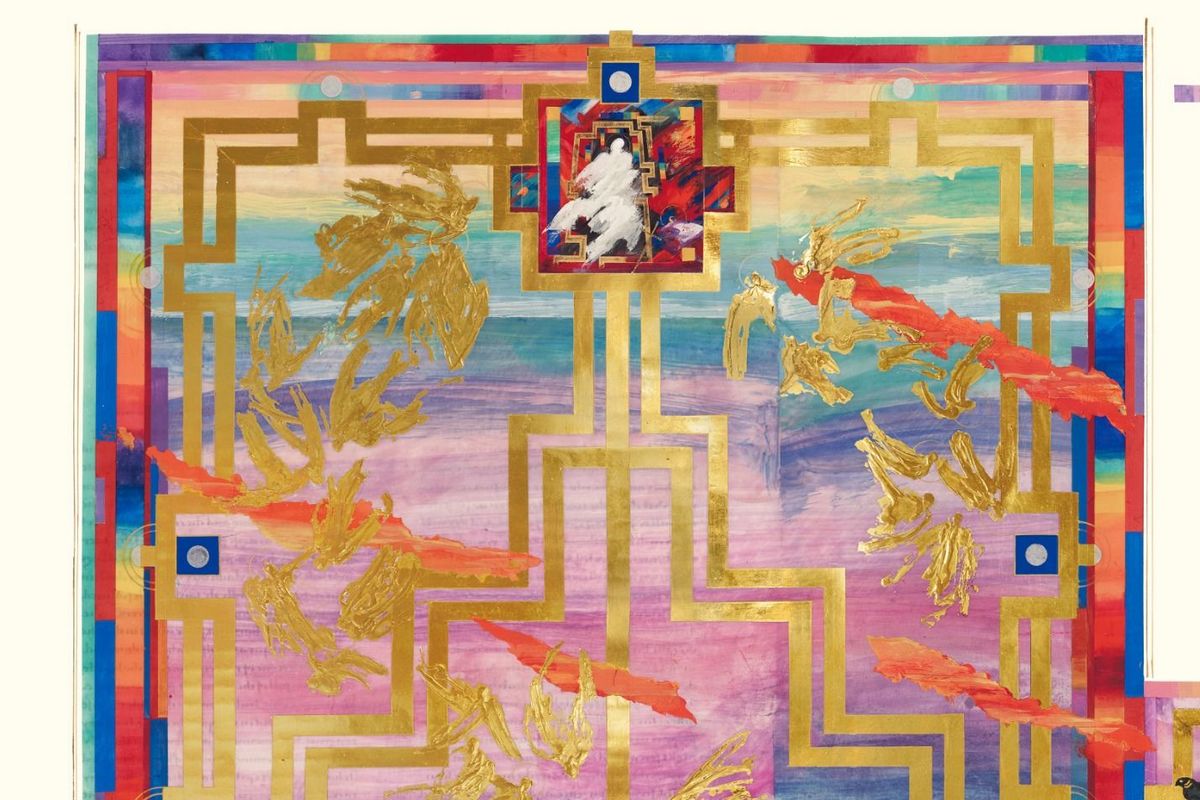

Featured Image: Vision of the New Jerusalem, Donald Jackson, Copyright 2011, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.