Advent’s momentum simultaneously sends us in two directions. Initially, we turn back and look toward the nativity narratives for the affirmation of the God whose becoming-human has changed, and continues to imprint, God’s form upon us. We ponder with Mary the mystery of this miracle, and we take up Luke and Matthew to recall his entrance into the world. The Word-Made-Flesh is approached by shepherds and kings alike, and we too are invited to come and see the wonder of God’s love. Kneeling in Mass during Advent reminds us that we kneel before the child whose narrative gives ours meaning—both individually and together in history.

Yet, the more we listen to the prophetic readings that resound throughout the season, the more we begin to feel the eschatological pull that turns our gaze to the end of time, when Christ will come again, and the momentum it creates. Here Christ’s approach is not one of natal humility, but rather we find the arrival of the slain Lamb from the Book of Revelation. The divine Word Incarnate bears bloodstained robes and the majesty of the crucifixion transfigured. We are drawn into awe once more, but this time in response to the unsettling, apocalyptic symbolism that looks like something out of a Flannery O’Connor short story and breaks into our festivities.

Trying to join Christmas’ peace to the Johannine imagination becomes quite the herculean task, where the portrait starts to bear the appearance of the doubleness of the Greek icon the Pantocreator, leaving us to squint at the bifurcated image of God and question—do the two halves really cohere? The readings leading up to Christmas look like some kind of aesthetic trick, like the painted over eyes of the Lamb in the Ghent altarpiece. We have only to wait Advent out in order to find the intensely merciful and human eyes of the Incarnation’s Christmas marvel dwelling beneath all along.

The season’s liturgies, however, impress upon us that we ought not skip ahead. Advent’s eschatological framework is not an accidental blip that frustrates an otherwise merry season. On the contrary, these weeks implore us to focus on the celebration not only of the God-made-flesh, but this God’s sacrificial impact upon time and history. The creedal affirmation that “we look forward to the Resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come” reverberates loudly. This is the time where we rejoice in the God-who-became-human and all that his lived drama entails, and where we actively await his coming again.

In the eschatological posture of baited breath, Advent challenges Christian believers. John the Baptist heralded Jesus’s arrival, and his voice reaches us today. We too are to repent and prepare the way of the Lord, for Christ is still to come at the end of time, and like the wise virgins, we must come with sufficient oil. The God whose love led him to the Cross comes to us as in Matthew 25, taking note of how well we have not only served and remembered him in our lives, but also how well we have seen and worshiped his presence in our neighbors. For as truly as the Kingdom of God is proclaimed as “already” in the Gospels, it is also always “not yet.” There remains much work to be done building the Kingdom through participation in the sacrificial form of love that reaches out to the marginalized, that freely offers charity’s excess, and that is willing to suffer for the sake of another’s suffering.

The ethics of Advent as eschatological ethics ought to radically enjoin us to embrace our neighbors, and not just the comfort of familial warmth. In many senses, we are constantly reminded of this as we go about our Christmas shopping. You cannot enter a store in December without hearing the metallic peals of a Salvation Army Bell, and cues in various media advertisements remind us that this is the season of giving and generosity. But before we pat ourselves on the back for dropping our spare change into the red bucket in Walmart’s entryway after we dropped exponentially more on a Black Friday deal, we might do well to look more deeply at the biblical idea of charity, and reflect on what this means for us who are living with the anticipation and hope of Christ’s imminent return.

Expectation marks the posture of Ancient Israel, much as it configures the Church’s in Advent. In Israel’s history God makes himself known, yet the fulfillment of Israel’s promise is also still awaited. As Old Testament scholar Gary Anderson argues, charity comprises a significant part of Israel’s teleologically framed ethics. Although Anderson notes there is a transition between the ancient idea of a commandment as “mitzvah” and the postbiblical dominance of charity as a primary form of keeping God’s commandments, he points out that charity’s centrality is woven into the very fabric of Israel’s understanding of their relationship with God.[1] Temple service and almsgiving are inherently linked, Anderson declares—giving to the Temple, and thus to heaven, joins donations to the poor, or one’s neighbor, as part of the world’s economic rhythm. In other words, charity is not about “moral agency” of the giver, but rather about “the nature of the created order . . . Because the Holy One of Israel is a God of mercy, the world that he has made is an expression of that mercy . . . It is about giving testimony to the love of God inscribed in the natural order.”[2]

This view of charity differs significantly from modern approaches, Anderson claims, which he links to the Kantian version of moral duties.[3] While God commands his chosen people to be charitable to the poor, these commandments follow upon the world’s inherent structure and logic. Those who are the imago Dei mirror the divine benevolence that freely initiated a world of abundance and dynamic exchange, and giving provides an important mode by which human activity looks like God’s. Moreover, by acting charitably, humans strengthen their relationship with God. While all creation enjoys the gift of relationship with the divine transcendence that begins, orders, and sustains existence, humans have the opportunity to dynamically engage the God who speaks with them and works through them, and charity has a prominent role to play in it all.

We can see a practical expression of this teleological mirroring in both aspects of charity that Anderson explores: charity as noninterest-bearing loans to those in need, and charity as almsgiving (gift) to the poor. While we might not think of today’s loans as a form of charity, Anderson points out that they provided an important expression of it for writers like Ben Sira (Ecclesiastes) and the authors of Proverbs. To lend to one’s neighbor enacted a dynamic economics of charity for the material wealth within Israel. Rather than leaving wealth to stagnate in storehouses, loaning put material resources into active and continuous circulation. To expect repayment on a loan provided the lender means to share with another neighbor, and the lender was prohibited from earning interest on the back of the borrower. Wealth was not meant to sit idle, and through loans it could provide support to multiple needy members of the community.

Although Ben Sira and Proverbs both caution lenders, worried that there were great risks involved in loaning money to those who might defraud or default in repayment, they also include direct commands to those with means: “lend to your neighbor in his time of need,” “be patient with someone in humble circumstances, and do not keep him waiting,” and even “lose your silver for the sake of a brother or a friend, and do not let it rust under a stone and be lost.”[4] Despite the risks, charity was an important way for material benefit to be shared within Israel’s community. As Anderson notes, however, Ben Sira’s injunction to “lose your silver . . . on behalf of the poor . . . [harbors] no pretense . . . that the funds will be returned.”[5] Much as loaning is a distinct part of charity’s work, so too is giving without expectation of repayment. The melding of these two ideas in Ben Sira’s verse reveal their deeply interconnected nature. Both put material wealth into active circulation. Both relieve the recipient of the accumulative burden of interest and forced repayment. Both mirror God’s generosity within Israel’s horizontal economy.

Still more accrues than the merely horizontal by charitable acts; charity is far from a closed system of human economics. Anderson argues that God’s relation to earth’s material exchange deeply impacts charity, both in what the material signifies as well as what it generates. The reason the authors of Proverbs and Ben Sira could both caution lenders on the one hand, yet nevertheless commend them to generosity on the other, has to do with charity’s intertwined connection to Israel’s relationship with God. God stands behind all aspects of charity, which not only generate material sufficiency horizontally, but also generate spiritual wealth, or “treasure in heaven.” As Anderson explains,

Whereas the collection of interest normally benefits the creditor and harms the debtor, just the opposite is true for the divine economy. The debtor owes no interest while the creditor collects it just the same. This is because the giving of alms is not just a horizontal, this-worldly affair. When one treats the poor kindly, one finds oneself before the altar of God.[6]

Using Catholic vocabulary, charity acts sacramentally. It places one before the real presence of God. Moreover,

What constitutes an almost certain loss of wealth in earthly terms becomes the privileged means of securing it in heaven . . . [and] the poor person serves as a sort of conduit through which one can convey goods from earth to heaven . . . of a very special nature because both the donor and the recipient stand to profit from this transaction.[7]

Charity wicks the world’s horizontal activity to heaven, and the donor stands before God not empty-handed, because he lent on earth, but full of heaven’s treasure, conveyed by the very one to whom he donated.

The Old Testament notion of a “treasury in heaven” signals not a storehouse of earthly points accrued and tallied by God, but rather functions as a distinct contrast to the earthly accumulation of material wealth as “treasuries of wickedness.”[8] Unlike earthly hoarding, the treasury of heaven acts as access to the deep reservoir of God’s mercy—described as that which “will rescue you from every disaster . . . fight for you” and ultimately act as “deliverance from death.”[9] True wealth is something that grows, but the image of a “storehouse” changes. Rather than a material silo, we find a spiritual deposit whose creditor backs the fortune, is its power, and provides the riches assured. In short, by building a treasury of heaven, you build the wealth of a stronger relationship with the God whose memory saves Israel time and again.

However, these well-insured treasuries of heaven’s salvation do not lessen the difficult labor that charity’s love is. On the contrary, the deep and demanding faith required of those who give functions as a recurrent and climactic point in Anderson’s work. Even if God stands behind and intimately blesses the charitable one’s donations, giving still demands a Kierkegaardian leap of faith. Acts of charity closely parallel, if not outright constitute, the most meaningful acts of faith. The book of Tobit provides fertile ground for Anderson’s argument. Tobit not only behaves charitably in tough times, but persists in his charitable activities even in the worst of times. Unlike readers who classify this book as a Deuteronomistic novella, where the righteous are duly rewarded for their goodness, Anderson argues that a much deeper lesson is imprinted in the heart of the book.

The text follows the story of a righteous man, Tobit, who lives in the northern kingdom of Israel at the time of its fall to the Assyrians. Not only does Tobit exhibit exemplary Torah faithfulness before his political exile, sending gifts to the Temple in Jerusalem and performing many mitzvot, but he persists in charitable activity as risk to himself and his family increases when he is forced into exile in Nineveh, the capital city of Assyria, must endure the shifting weathervane of political favor. Moreover, he teaches his son the value of charity when the world seems to crumble around him—bird droppings literally blind his eyes, he loses the means of providing for his family, and he must face the difficult decision of whether to send his only son—the material incarnation of his and his wife’s future—on a journey riddled with peril to secure his family’s finances and open the door for covenantal progeny.

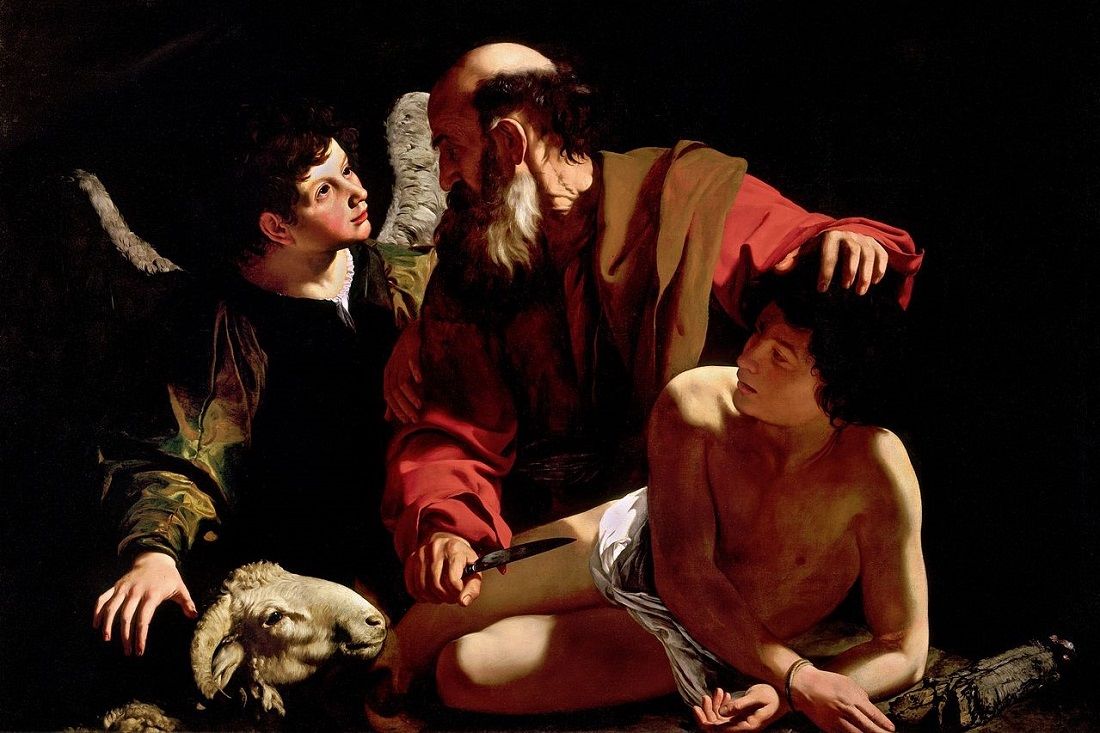

Like Job, Tobit refuses to relinquish his beliefs in the midst of a living hell on earth as his body fails him, his wife reproaches him, and he loses his son to the unknown. Like Abraham on Mount Moriah, Tobit’s charitable deeds expose deep and abiding faith in the God he (literally) cannot see and whose promises of blessing are hidden in deepest obscurity. As Anderson notes, the irony at the book’s center “is breathtaking,” and here resides the work’s vital heartbeat.[10] Although Tobit receives blessings in abundance by the end of the story, Anderson cautions against a reductionist interpretation of his trials and their significance. Readers are not meant to walk away from the tension of Tobit’s drama into the lulled reward of the conclusion. On the contrary, charity in Tobit presses one to see the absurdity and astounding faith required by charitable activity.

When we study the Akedah (Genesis 22, that, is the so-called “binding of Isaac”) through Kierkegaard’s eyes, he demands that we confront the seeming impossibility of Abraham’s act (leap) of faith. To water down Abraham’s sacrifice—of the absolute and unbreakable ethics that bond parents to their children in love—is to destroy the complete alterity that Abraham’s faith demands of him. As Kierkegaard notes in his pseudonymous voice, “this courage I lack”[11]—he cannot fathom the leap of Abrahamic faith as a mere mortal. Something else—something Abraham had access to that Kierkegaard’s Johannes de Silentio does not—is necessary for such a dramatic and life-altering decision. “Faith is . . . no aesthetic emotion, but something far higher . . . it is not the immediate inclination of the heart but the paradox of existence.”[12]

How, then, are we to reconcile these concurrent yet disruptive ideas that Anderson presents, where charity is both part of the teleological, natural fabric of the world’s horizontal and vertical relationships, yet where it also presents a Kierkegaardian aporia of absurd impossibility, which changes the very fabric of existence and seems to exceed both the comprehension and strength of human beings? How can Tobit’s Joban framework, infused with the heartbeat of the Akedah, meld with the teleological order of the world? If we turn to the New Testament, though, another narrative emerges that sheds light on this seemingly impossible connection. All three Synoptic Gospels tell a story about a rich man who approaches Jesus, asking what he must do to inherit eternal life, and like many synoptic passages, each rendition impacts the meaning imparted. In Mark’s version in particular, we find resonances that help us parse the eschatological ethics of charity that confront the teleology inscribed into the Old Testament’s as well as the Gospel’s reinterpretation of its aporetic impossibility.

Here we encounter a rich man in the posture of righteous obedience. Unlike Matthew’s iteration, where we can almost hear the snide tone in the rich man’s voice as his interrogatives try to calculate the math of good deeds he must accomplish to inherit eternal life, Mark depicts a man who seems, in many ways, superior to the disciples who surround Jesus every day. Where Jesus’s followers continuously bumble and fail to understand his teachings, the rich man rushes to and kneels before Jesus, opening his mind and body in a posture of humility, and hails him as “Good Teacher” (Mark 10:17). He listens to Jesus’s response that one must keep the commandments, and replies again with respect: “Teacher, I have kept all these since my youth.” (Mark 10:20). This man is not only acting in accordance with God’s covenant, but he is open to learning more. He has already put himself in right relationship with the vertical and horizontal laws of God. If we consider what this means in light of our reading of charity as part of the commandments for faithful living, as given by Proverbs and Ben Sira and reaffirmed within Tobit’s narrative, we ought not be surprised by Mark’s line: “Jesus, looking at him, loved him” (Mark 10: 21).

But this is not the end of the 21st verse. After gazing at the rich man with love, Jesus issues two more commands: “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mark 10:21). What Jesus asks is more than the man had done before—now he is tasked with selling what he owns and giving the proceeds as alms, before leaving what he knows to follow Jesus. Like Tobit, charity will perform the litmus test of human faith as the rich man faces charity’s expanded borders and the crossroad of a momentous decision. Also like Tobit, he is asked to leap into a world that seems prima facie absurd—he has already kept the commandments well and yet is asked for deeper faith that would surrender and give back every material blessing received. Albeit as Tobit’s mirror image in blessing’s comfort rather than exile’s blinded Sheol, the rich man faces his own sacrifice of Isaac.

Unlike Abraham and Tobit, the rich man fails the test. He turns away shocked and grieving, “for he had many possessions” (Mark 10:22). The story continues with Jesus’s warnings about the difficulties of the rich entering the kingdom of heaven, noting “how hard it will be for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:23) such that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25). Based on the rich man’s failure and Jesus’s subsequent proclamations, it seems as though the didactic lesson of wealth is clear. Even if wealth is not funding a miser’s hoard (or what Anderson describes in the Old Testament language as the “otserot resha,” a “treasury of wickedness”), it hinders faith’s trust in God, which is the only real way to fund the “treasury of heaven,” (“otserot tsedaqa”) or the riches that charity’s faith generates.[13] Matthew and Luke seem to pronounce the same verdict on the rich man and his wealth. In every telling, the rich man turns away from Jesus’s demands. Each time, Jesus repeats the same demands.

Like us, the disciples look at one another astounded, asking “then who can be saved?” (Mark 10:26). If this is cautionary tale, it comes across as a harsh one, even to those who have given up what they own to follow Jesus. Their perplexity surely does not diminish with Jesus’s explanation, as he looks at them and says “For mortals it is impossible, but not for God; for God all things are possible” (Mark 10:27). Yet this is a strange expression indeed if the story is meant to critique human weakness regarding material possessions. If God can act to do anything, why demand acts of generosity from humans? Furthermore, is God commanding the impossible just to make a point about human frailty and divine potency?

Here we must answer no, unless we are comfortable with a God who seems calculating and manipulative as he positions the rich man to act as a mere rube to make a greater point. Many interpretations of this gospel story avoid Jesus’s words here entirely and work to unravel the fraught mystery in the narrative. Well-intentioned sermons return to the figure of the rich man, looking for fault. They attempt to separate the rich man’s wealth from congregants’ own stock options and savings accounts, either by casting aspersion on the rich man’s character or his psychological attachment to his possessions, or by demonizing the wealth he owned as itself tainted and corrupted by its unknown yet surely ill-gotten means. At least in Mark’s Gospel, however, the story fights against both interpretations. We know that the man appears as a good and attentive disciple open to learning, and Jesus looks at him with love. His is not the call to repentance, as with Zacchaeus, where defrauding neighbors impacts vertical and horizontal domains. He has been practicing an economics of charity by keeping the commandments—his wealth is not a treasury of wickedness but seems to be in keeping with the covenant. We must not shy away from the more complex lessons of Old Testament on charity if we are to understand the entirety of this story, including Jesus’ enigmatic proclamation. Like Anderson’s reading of Tobit, this small gospel tale offers much more than meets the eye if we redirect our gaze to its center.

If we hold Tobit and the rich man as our two indices of the leap of faith that charity demands, we find two contrasted portraits of one who leapt into charity’s province beyond reason and one who could not. Where Kierkegaard laments his inability to imitate Abraham’s leap into faith’s absurdity, though, we should resist the temptation to follow suit. The late words in Mark’s story are neither condemnatory of human failure nor exonerative of human effort. On the contrary, they point us to a deeper truth about the grace that faith’s leap requires. What Kierkegaard never references in his own probing of the Akedah is the fact that it is God who calls Abram in Genesis 12, God who corrects his missteps with Sarai in Egypt, and God who continuously reaffirms the promise during Abraham’s journey. Although Abraham’s willingness to respond to God is critical in the story, so too is God’s activity throughout. God is the one who offers the impossible and brings it to fruition along the way. Grace is that which journeys with and perfects nature. Only by grace is the impossible possible.

Moreover, such grace is also that which works through the multitude of human failures. The rich man is a far cry from most of the Old Testament fathers and mothers of faith, just as he is a far cry from Mark’s blinded disciples who never seem to grasp the reality of who Jesus is in the Gospel. We know that the rich man has not murdered (as did Moses), committed adultery (as did David), or defrauded his neighbor (as did Jacob). But he is still the one who comes up short. He walks away from Jesus sad, because he cannot enact Jesus’s commands of charity and discipleship. While we could view this failure in line with the Reformation’s general condemnation works-righteousness, we should not be so quick to dismiss the cruciform imprint upon grace that transfigures and perfects the entirety of human drama, both good and bad. Grace is that which makes the impossible possible—it is that which raises the dead to life and transfigures sin’s wounds into resurrection’s corporeal glory. It is that which the book of Revelation’s slain Lamb offers.

If we turn at the ending of the story of the rich man, we are directed back to its center, where Jesus looks at the rich man with love and commands him to further charity and discipleship. The story holds us in tension. If we try to distance ourselves from the way this man relates to his wealth or negate Jesus’ call to radical charity, we excise the Akedah of charity commanded by Christ as part of true discipleship. The seeming impossibility of what Jesus asks should not be removed simply because we cannot swallow its enormity. Neither should we abandon hope, like Kierkegaard’s Johannes, at our failures in acting out our faith. I may lack courage to give away all that I have, but Christ’s words promise the power of grace in the face of human failure. Grace works with our striving and transforms our weakness. The challenge of Jesus’s call to charity will always press us to the borders of the impossible, but it is also the challenge of the Akedah and grace’s perfecting work throughout our lives.

So perhaps the lesson we are left to ponder this Advent, as Mary pondered the news of Jesus’s hastening birth, is one that revolves around the power of grace, the position of repentance, the meaning of charity in the eschatological posture of the season. We ought not, when facing this gospel story, reject the mirror held up to our faces. To prevaricate our shortcomings and refuse to repent for the times we have turned away from charity’s Akedah requires us to listen to John the Baptist’s call at the river. But we need not turn away in full dismay, as did the rich man. The teleological order of charity’s world is a longer journey than a single moment, and it is marked by grace’s action in our lives as we heed and fall short of Jesus’ commands. The mystery of the God-made-flesh is that of the God who looks at us and loves us, as much as the God who continuously challenges us to deepen our response to his call. We must look forward to his return with the work of the Kingdom ongoing—always already accomplished through his sacrifice and yet always not yet as grace perfects the nature it saves—and we must turn into, rather than away from, the charitable press of the season.

[1] Gary A. Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 16.

[2] Ibid., 32.

[3] Ibid., 4. Although Anderson does not specifically reference Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, his allusion to duty’s conjunction with charity resonates with Kant’s notion of benevolence as an imperfect imperative in section 4:423 and 4:430. While the inescapable “duty” of the categorical imperative “is indeed not to be found,” benevolence and other imperfect imperatives “add ‘harmony’ to the principle of humanity—to not simply ‘preservation’ in non-contradiction but with the advancement of humanity as such” (emphasis Kant’s).

[4] Ben Sira 29: 4-7, 9. As quoted in Anderson, 47-48.

[5] Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition, 48.

[6] Ibid., 32.

[7] Ibid., 49.

[8] Ibid., 54–55.

[9] Proverbs 10:2, 11:4. As quoted in Anderson, 56.

[10] Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition, 97.

[11] Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin Books, 2006), 36.

[12] Ibid., 53.

[13] Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition, 54.