In the second grade, my mother asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I replied with what I saw as the two most appealing occupations—I would either become a veterinarian or a saint.

While many Catholic parents’ eyes might begin to brim with tears at such a declaration, my knowing mother asked a prescient follow-up question. Do you know that you have to die before being canonized a saint? With the swift and definitive logic of an eight-year old, I promptly concluded that sainthood was not the professional trajectory for me. I set my sights instead on a future concerned with animal health. The subsequent parental encouragement that everyone was called to sainthood over their lifetime, no matter their job, did not sway my decision. If I could not get the credit for being a saint, what was the point?

This story makes great Catholic cocktail party fodder. Everyone smiles and chuckles at my former precociousness. I feel great satisfaction in having a good anecdote in my back pocket for just such occasions. It does not hurt that my professional life turned out to be in academic theology—the story gets a lot of mileage. I like to think that I have moved beyond the logic of an elementary school child, but every time I use my charming story, I realize that I really have not.

We all look for credit in so many ways—through the recognition of professional output, the gratitude of a spouse or significant other, or the affirmation of family members who see how wonderful you really are. None of these are bad in themselves, and in fact quite the opposite. It is a delight to see and rejoice in the goodness of the people and world around us. Getting credit, though, can cloud another important part of life—namely, the way that sanctity is rooted in the logic of sacrifice.

Augustine opens his Confessions with a reflection on the selfishness of infants. I love teaching this portion to undergraduates, surveying their shocked reactions to this man who pins sin on a child’s desire to satisfy hunger pangs. How can crying out for what we need be evil? Surely Augustine has gone one step too far.

In this early reflection, we see Augustine thinking through the nature of sin and the measure of its impact on humanity. From the earliest moment, even within the womb, Augustine argues that human beings are marked by the original consequences of Adam and Eve, which echoes in their actions and decisions from infancy through adulthood. Even before we have fully conscious responsibility, we enter into the logic of a world that is fallen. Sin touches every part of human life—my needs are set against another’s. Augustine’s claim on his mother’s milk takes the food that his own brother requires.

In a sense, Augustine radicalizes what Gregory of Nyssa writes at the outset of his reflections in The Life of Moses. The truth of being born, Gregory says, is not simply an external set of circumstances beyond our control and responsibility. On the contrary, “birth occurs by choice. We are in some manner our own parents, giving birth to ourselves by our own free choice in accordance with whatever we wish to be . . . molding ourselves to the teaching of virtue or vice.”[1] Both Augustine and Gregory add weight to this initial moment of human existence not to join a fully-formed reason to an infant’s reactionary will. Hardly. Rather, they return to the beginning of human life to underscore an important point. Namely, the most basic needs of a human being are not exempt from the corruption of sin, and the smallest aspects of life require conscious choice. Everything requires redemption, and the life of virtue is not a life that we fall into by accident. It is, rather, a life made by decisions wherein we embark on a journey up Mount Sinai toward God.

It is easy to revel in the thought of sacrifice. Part of my rationale behind wanting to be a saint as a child was wanting to make the “big sacrifice” for God. Beyond the vainglorious desire for accolade, I wanted to give everything I had in a moment of total generosity that mirrored the martyrial offerings of so many saints. I just did not particularly want to die to do it.

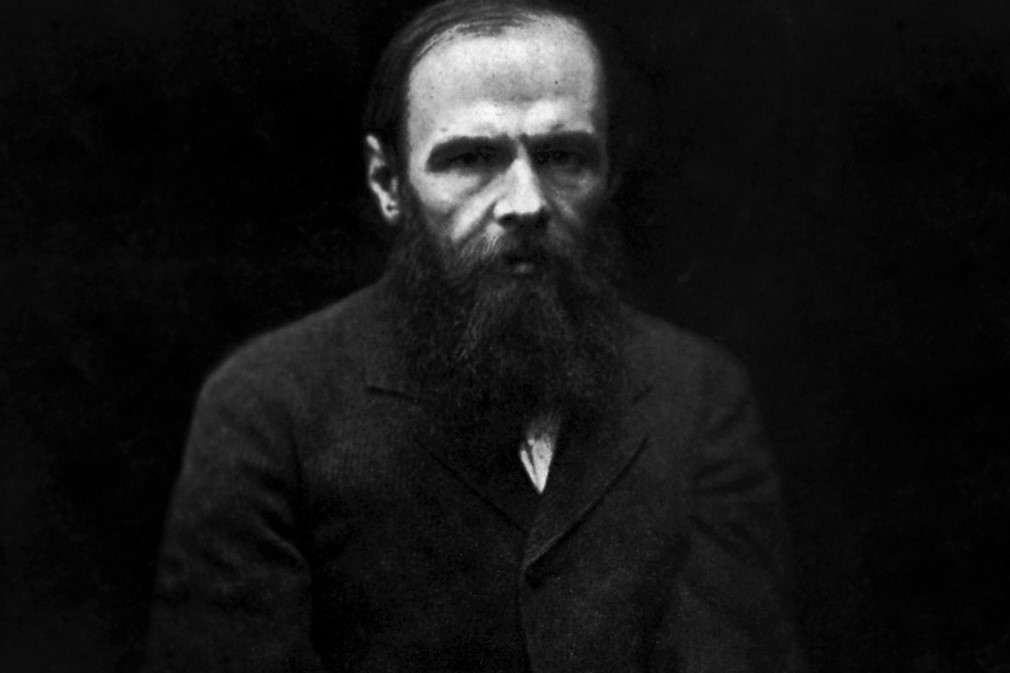

Fyodor Dostoevsky, through the voice of Father Zosima in his The Brothers Karamazov, points out that it is very easy to think that we love one another when we are doing precisely that: thinking about loving. The widow who approaches Fr. Zosima gushes:

I love mankind so much that—would you believe it?—I sometimes dream of giving up all, all I have . . . and going to become a sister of mercy. I close my eyes and, I think and dream, and in such moments I feel an invincible strength in myself. No wounds, no festering sores could frighten me. I would bind them and cleanse them with my own hands, I would nurse the suffering, I am ready to kiss those sores.[2]

Fr. Zosima remarks that the widow’s disposition is good and a credit to her—she may “once in a while, by chance . . . do some good deed.”[3] Her thoughts, though are far from the active love that the elder knows actually reflects the life of faith. “Active love is a harsh and fearful thing compared with love in dreams.”[4]

What we need, and what Dostoevsky, Gregory of Nyssa, and Augustine press us to understand, is the kind of sacrificial love that weds sanctity to the everyday. It is something we are called to from the first moments of our life to its final end in death. This kind of sanctity is neither glamorous nor easy. In fact, it is probably all the harder given our efforts to rationalize and glorify our own actions as we attempt to magnify the importance our undertakings rather than understand precisely what they are—tiny, minute choices in the everyday that one by one contribute to a life of holiness or vice.

Taking out the trash one night doesn’t make one a saint. Taking out the trash every day with a good disposition, and the host of other tiny tasks that one must do when living with and loving another, paves the way of holiness.

This kind of sacrificial living, or the daily “little way of love,” is best known in the writings of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. She remarks in a letter to her sister, Céline, that “you know well that Our Lord does not look so much at the greatness of our actions, nor even at their difficulty, but at the love with which we do them.”[5] The love that Thérèse refers to, though, is not a feeling or a thought. It is, rather, the way her smallest actions interconnect with the larger spiritual orientation of her life, namely, as deeply interconnected with Christ’s death and the mystery of the Triduum.

Hans Urs von Balthasar focuses on this aspect of Thérèse in his book Two Sisters in the Spirit, where he pushes beyond the saccharine elements of this saint’s style and into the mysterious yearning she speaks of as the desire to stride into the depths of darkness with Christ. Balthasar specifies that Thérèse does not write with a savior complex. On the contrary, she recognizes a deep spiritual truth about the nature of sacrifice—that every sacrifice connects to the mystery of the cross—and the myriad of ways that her life of prayer in a French convent expresses this truth. Precisely because she is connected to Christ’s mystical body, which Thérèse and all Catholics continuously recognize and celebrate in the Eucharistic, Thérèse is brought into the mystery of Christ’s redemptive work.

She does not replace her savior but accompanies him. She participates in the power of a God who does not substitute perfection for brokenness, but rather works inside brokenness so that it might configure to glory. The power that transfigures Christ’s broken body is that which transfigures every moment offered up. The cross stands at the center of the little way of love.

To sacrifice our everyday, no matter what that might entail, is no mere metaphor for Christians. It is, rather, a profound participation in the mystery of the cross and resurrection working through history. It is the mystery of our lives being remade from the inside out and of the world being reborn. “Active love is a labor and perseverance,”[6] Fr. Zosima reminds us. Building a life of virtue and journeying up the mountain takes a lifetime of steps and our willingness to take up all of our crosses along the way. But we should be encouraged on our journey. We never need fear that our great moment of martyrdom has passed us by, or that we lacked courage in one defining moment and have missed out on a saint’s vocation. On the contrary, it is precisely in the smallest sacrifices that we find the wood of the cross and the power of resurrected glory. We become saints, precisely, in the sacrificial love of the everyday.

[1] Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, ed. John Meyendorff, trans. Abraham Malherbe and Everett Ferguson, New edition edition (Mawah, NJ: Paulist Pr, 1978), 56.

[2] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: FSG, 2002), 56.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 58.

[5] St Thérèse Lisieux, The Letters of St. Therese of Lisieux, Vol. I: 1877-1890, trans. John Clarke, Centenary Edition edition (Washington, D.C: ICS Publications, 1982), 468.

[6] Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, 58.