It was during a visit to the Holy Land in the summer of 2019 that I first got to know one of history’s most mysterious saints. While sitting at the base of one of the many columns in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I found myself meditating on Saint John’s description of the first encounter between Mary Magdalene and the Risen Lord (see John 20:11–18). Realizing I was just a few feet away from the spot where this profound exchange took place brought tears to my eyes.

Later on that same trip, one of my fellow pilgrims recommended to me a book by an Irish priest called Fr. Sean Davidson. The title of the book was Saint Mary Magdalene: Prophetess of Eucharistic Love, and my friend assured me that it did a good job clarifying the various Marys who appear on the pages of the Gospels.

Upon reading Davidson’s work, I quickly learned that the enormous cult to Mary Magdalene that existed during the Middle Ages was animated by a very particular perspective. From its earliest days, Western Christianity championed the view that Mary Magdalene is simply another title for Mary the sister of Martha and Lazarus, whom today we tend to call Mary of Bethany; and they further identified this Mary with the unnamed sinful woman who anoints the feet of Jesus in the seventh chapter of Luke’s Gospel.

Thus conceived, Mary Magdalene garnered extraordinary appeal throughout the Middle Ages as a potent symbol of what God’s grace could accomplish in the hearts of his wayward children. The popular portrayal of her as a reformed prostitute (a characterization never explicitly stated in Scripture, but often inferred on the basis of Luke 7), far from being an attempt to denigrate her, served only to strengthen ordinary people’s devotion to this fascinating heroine. Here was one who had dramatically overcome her vices, offering hope to the most hardened sinner.

Although a number of Eastern Fathers took a different view, this vision of the Magdalene as sinner-turned-saint became the consensus position in the West for over a thousand years. Yet today the traditional view has been almost entirely rejected. With the rise of critical scholarship in the twentieth century, it became increasingly fashionable for academics to dismiss the ancient devotion as pious reverie. Some feminist scholars went even further, arguing that by depicting the saint as a reformed prostitute, the Medieval Church was actively trying to disparage the role of women in the Christian community.

I think these critics are wrong, and I am convinced that the Medievals and the early Western Church got it right. I shall therefore attempt to recover the alluring yet elusive figure of Mary Magdalene as presented to us in the canonical Gospels. On the basis of what the French exegete André Feuillet termed a “convergence of probabilities,” I shall argue, first, that Mary of Bethany is very likely the same person as the “woman of the city, who was a sinner” (Luke 7:37). Secondly, I shall argue that a plausible case can be made for the further identification of this composite figure with the person of Mary Magdalene.[1]

If my argument is successful, then it demonstrates that the traditional Western view remains exegetically reasonable, and believers today can be intellectually justified in holding to the ancient devotion. In addition, it suggests that modern critics have been overly hasty in jettisoning—and, more often than not, ridiculing—some fifteen hundred years of liturgical and hagiographical testimony which favors the traditional view.[2]

In making this case, I have freely drawn from Fr. Davidson for inspiration. Like him, it is my firm conviction that if the traditional depiction can be vindicated, then Mary Magdalene shines forth as a far greater saint as a result—a vivid instantiation of John Henry Newman’s “Saint of Love,” the model of perfect penitence whose heart burned with ardent longing for her Master and Friend.

Two Anointings

We begin by examining the reasons for identifying Mary of Bethany with the woman from Luke 7. An unwelcome roadblock for homilists today is the seeming surfeit of nameless women in the Gospels coming to anoint the feet of Jesus with their hair. For the bulk of the Western tradition, however, it is evident that there were two anointings, and only two.

The first of these, delineated only in Luke, is the scene of an anonymous “woman of the city, who was a sinner” who comes to Jesus with a flask of ointment and uses this, mingled with her tears, to wipe his feet (Luke 7:37). The interaction takes place in Galilee, in the home of a certain Simon the Pharisee.

While this occurrence would be considered outlandish enough in our modern milieu, it is all the more jarring given the social customs of the time. For a woman to let down her hair in public was regarded as scandalous, and for this woman to then anoint the body of a male rabbi was shocking in the extreme. To make matters infinitely worse, the woman in question is a notorious character with an ill-earned reputation. Aware of his host’s cynicism over what is taking place, however, Jesus praises the still-unnamed woman for her bravery and bids her to depart in peace.

This poignant Lucan episode is made confusing by the fact that the other three Gospels also record a woman anointing the feet of Jesus (see Matt 26:6–13; Mark 14:3–9; John 12:1–8), but under quite different circumstances. Unlike Luke’s anointing, which occurs at the beginning of Jesus’s ministry, this second anointing is described as taking place just a few days before his death. Furthermore, the location of this latter anointing is not in Galilee, but almost a hundred miles to the south, in Bethany at the home of another Simon, this time described not as a pharisee but as a leper. And whereas the Luke 7 woman bore a demeanor of tearful repentance, the woman in this second episode shows no sign of tears.

According to mainstream Western tradition, therefore, a close reading of the Gospel texts reveals two distinct “anointing episodes” in the ministry of Jesus. The first is described in Luke 7, and the second in Matthew 26, Mark 14, and John 12.[3] Significantly, whereas Matthew and Mark leave their female anointer anonymous, John goes out of his way to identify her as Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus (see John 12:3).

Against this traditional interpretation, critical scholarship has at times sought to collapse the anointing passages into one. For skeptical exegetes, the idea of two separate women performing such a bizarre deed is sufficient proof that one or more of the evangelists have twisted the facts. Strength is added to this critique by the fact that all four Gospels describe the event as taking place in the house of a man called Simon. It would seem, so this skeptical argument goes, there was in reality only one such event, roughly captured in Matthew-Mark-John, and Luke has adapted the historical record in order to better accommodate his literary-theological narrative.

Tempting though it may be, this reductionist approach falters on theological and exegetical grounds alike. Careful historian and inspired evangelist that he is, Luke cannot be summarily dismissed as having wildly altered all the pertinent facts of the event. Moreover, we know from the research of Richard Bauckham and others that “Simon” was the single most popular male name in first-century Palestine; no less than 15% of Jewish men bore this name.

Collapsing the two anointings into one on the basis of first names alone, therefore, does damage to the biblical text. The skeptical view likewise fails to account for the fact that the two anointings take place in entirely different locations at entirely different points in Jesus’s ministry and under completely different circumstances. Per Ockham’s Razor, the traditional view, therefore, remains the simplest and most compelling explanation.

Yet the problem persists. Although the skeptical approach is unpersuasive, it makes a worthwhile point: the kind of event described across all four Gospels is very outlandish, such that the similarities between the two anointing events appear uncanny. Just how likely is it that two different women would think to interrupt a dinner party in dramatic fashion in order to perfume Jesus’s feet while using their hair as a towel? Hence, we are met with an exegetical antinomy: there are too many convergences for these anointings to be two entirely unrelated episodes, but we must be equally distrusting of critical attempts to collapse the two events into one.

One Anointer

It is in the face of this knotty problem that the Western tradition offers us a percipient solution. In the words of Fr. Davidson, following Henri Lacordaire, there were “two different anointings indeed but one heart conceived them both . . . . Only this conclusion allows us to hold the differences and similarities in perfect balance.”[4] Here the integrity of the Gospel texts is maintained, but without relying on the extreme unlikelihood of two different women performing such an unconventional deed. Rather, as Fr. Davidson observes, it is the same woman in both anointings, yet these represent two very different stages in her relationship with Jesus.

On the traditional hypothesis, this woman—identified in John’s account as Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus—grew up in Bethany in a devout Jewish home but later fell away from her childhood faith, moving up north to Galilee and there becoming embroiled in a life of sin. At some point, she encountered the preaching of Jesus; Luke 7 recalls the moment of her coming to the Savior in tearful repentance. Overwhelmed by the grace of conversion, she gratefully places the shame of her former life at his feet.

From there, this notorious Mary becomes an avid follower of Jesus and one of his closest friends. Now fast forward a couple of years. Mary is back home in Bethany. Sensing that her master’s time on this earth is drawing to a close, she once again steps forward to anoint his feet—a gesture captured by Matthew, Mark, and John. This time tears are absent, but the mood is no less solemn as she silently reenacts the intimate gesture which marked the beginning of her walk with Christ.

In addition to the explanatory power it possesses, this traditional reading enjoys explicit textual support in John’s Gospel. In John 11 we find a cryptic verse: “Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and wiped his feet with her hair; her brother Lazarus was ill” (v. 2). Here John tells his reader that Mary “anointed” (aleipsasa) the feet of Jesus, and he employs the aorist tense in Greek to denote a past action. What makes the verse anachronistic, however, is the fact that Mary’s anointing has not yet taken place in John’s Gospel. In fact, the Johannine anointing will not take place until chapter 12, several weeks after the events of chapter 11. Taken at face value, therefore, John 11:2 clearly appears to identify Mary as the woman responsible for the earlier anointing recorded in Luke 7.

Faced with this conundrum, scholars who reject the traditional view will often try to read John 11:2 as a kind of foreshadowing. There are, however, two major flaws in this interpretation. First, it would be inconsistent with John’s grammatical usage of the aorist tense elsewhere in his Gospel. The figure of Judas, for example, was notorious to John’s readers as the one who betrayed Jesus. Yet when John introduces Judas, he does not describe him as “the one who betrayed Jesus,” but instead as the one who “was to betray him” (John 6:71).

Secondly, the skeptical approach fails to account for the fact that there were two anointing stories in circulation, not just one. If we are to infer, as modern scholarship increasingly does, that John’s first-century readers were familiar with the stories found in the synoptic Gospels, then we must assume they knew about the earlier Galilee anointing described by Luke. But if this is the case, then John’s decision to speak of Mary as “the” woman who performed the anointing only makes sense if there was clarity in his mind that of the two anointing stories circulating at the time, a single woman was behind them both.

A Consistent Portrait

The foregoing considerations render very probable the traditional hypothesis that the Gospels present two different anointing scenes, both performed by Mary of Bethany. This inference is based firstly on the inherent improbability of there being two separate women who performed such a peculiar deed, and secondly, on the basis of a straightforward reading of John 11:2.

We are now in a position to turn to the second major plank in the traditional view: the proposal that this woman is, in fact, Mary Magdalene. Although the Gospels never draw this connection in an explicit way, we shall examine eight lines of evidence that render it at the very least plausible, and perhaps even probable.

First, careful reflection on the ending of Luke 7 and the beginning of Luke 8 suggests a connection between the sinful woman of the city and Mary Magdalene. Immediately after Jesus tells the sinful woman to depart in peace, Luke introduces us to the Magdalene using a particular Greek construction (kai egeneto) which carries a strong consecutive connotation (see Luke 8:1–2). Luke then goes out of his way to attach special importance to Mary Magdalene, both by mentioning her first in the list of Jesus’s female followers, and by sharing the startling detail that she was formerly possessed by seven demons. Hence it is plausible to hold that his juxtaposition between the “woman of the city, who was a sinner” (Luke 7:37) and the woman “from whom seven demons had gone out” (Luke 8:2) is more than a mere coincidence.

Second, Jesus’s words about the day of his burial indicate that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are one and the same. Against Judas’s accusations of wasteful spending, Jesus comes to Mary’s defense: “Let her alone, let her keep it for the day of my burial” (John 12:7 RSV). Admittedly, this verse is somewhat obscure, and space limitations prevent us from discussing in detail its context and meaning. Nonetheless, a strong case can be made that the most compelling reading of John 12:7 can be found in the RSV and other traditional English translations. Hence John draws a direct connection between the Mary who anoints the feet of Jesus in chapter 12 and the Mary who travels to the tomb in chapter 20. Seemingly aware of the Marcan-Lucan tradition of the women going to the tomb to anoint the body, John zeroes in on the figure of Mary Magdalene. Here the words of Jesus in 12:7 are intended to echo in the mind of the reader: the work of anointing is not yet complete, and that is why Mary rises as early as possible to be reunited with the body of her savior.[5]

Third, the Fourth Gospel builds a literary connection between Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene. Intratextually, it is noteworthy that John stands alone among the four evangelists in recounting both the raising of Lazarus and Mary Magdalene’s conversation with the Risen Lord. These two great resurrection episodes mirror each other in a number of ways. Just as Mary of Bethany is known for weeping at the tomb of her brother (John 11:31, 33), likewise Mary Magdalene weeps at the tomb of her Lord (John 20:11). And whereas Jesus asks, “Where have you laid him?” (John 11:34), Mary later exclaims “I do not know where they have laid him” (John 20:2, 13, 15). At the intertextual level, it is noteworthy that John goes to the trouble of specifying Mary Magdalene’s observation that the two angels sitting in Jesus’s tomb were situated “one at the head and one at the feet, where the body of Jesus had lain” (John 20:12). If this is the same Mary who was famous for having anointed both the head (Matt 26:7; Mark 14:3) and the feet (Luke 7:46; John 12:3) of the Lord, then the inclusion of this ostensibly random detail would be fitting.

Fourth, the Fourth Gospel draws a literary triangle of sorts between Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalene, and the Song of Songs. As feminist scholars have rightly pointed out, John’s anointing scene in chapter 12 carries strong royal and bridal connotations. The description of Jesus reclining at table when Mary comes to anoint his feet is strongly reminiscent of Song 1:12: “While the king was on his couch, my nard gave forth its fragrance.”[6]

In like manner, John’s resurrection scene is a conscious attempt to invoke imagery from the Song of Songs. Mary Magdalene’s actions are remarkably similar to those of the Shulammite girl of Song 3 who wakes early to seek her beloved husband (Sg 3:1–2; John 20:1). Initially she cannot find him (Sg 3:2; John 20:2), so she converses with watchmen about where he has gone (Sg 3:3; John 20:13), and then finally discovers him with much jubilation (Sg 3:4; John 20:16). Just as the Shulammite girl clings to her beloved and refuses to let him go (Sg 3:4), similarly Jesus is forced to instruct Mary not to hold him (John 20:17).

What we find in John’s Gospel, then, are two Marys both closely associated with dramatic resurrection scenes, both closely connected with the imagery of the Song of Songs, and both portrayed as spiritual brides of Christ. On this basis, many within the tradition have inferred that John is deliberately (albeit subtly) identifying them as one.

Fifth, Matthew’s mention of “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary” at the tomb would be misleading to his readers if Mary of Bethany was a prominent figure in her own right in the early Church (Matt 27:61; 28:1). If the traditional view is mistaken, then Matthew’s wording becomes very confusing, since it is unclear whether “the other Mary” is a reference to Mary of Bethany or, alternatively, to Mary the mother of James and Joses, whom other Gospel traditions place at the tomb (see Mark 15:47; 16:1; Luke 24:10 ).[7] With these two Marys both holding celebrity status in the early Church, it would make no sense for Matthew to employ the lazy formula “the other Mary,” rather than the more considered “one of the other Marys.” But if Mary of Bethany was already known to be the Magdalene, then Matthew’s phraseology makes perfect sense. The only plausible candidate for “the other Mary” is the mother of James and Joses, and so he can word his narrative in the way he does without fear of causing confusion.

Sixth, there is considerable circumstantial evidence indicating that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are one and the same person. For starters, the identification explains how the son of a Nazarean carpenter became such close friends with a family from Bethany. The critics have no good explanation for this, whereas the proponents of the traditional view need simply posit that Jesus befriended the family of Bethany following his encounter with their wayward sister, Mary Magdalene. The identification of the two women also explains why Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene never appear in a scene together, and it further avoids the puzzle as to why not a single representative of the family of Bethany is named as having traveled the mere two miles to Jerusalem to be with Jesus on Calvary.[8]

Seventh, the traditional view is better positioned to explain how a woman from the small village of Bethany came to possess a jar of perfume worth tens of thousands of dollars in today’s money. The discrepancy can be explained by the theory that Mary Magdalene made a fortune for herself during her profligate years prior to her encounter with Christ—a fortune that enabled her to help bankroll Jesus’s ministry and to purchase the pure nard. Additionally, this would explain why Judas’s first thought upon seeing Mary pour the nard over Jesus’s feet was that if the ointment had been sold, then the money would have been allocated to the fund which he managed. If Judas knew Mary to be one of the main patrons of Jesus’s ministry, this would explain why he is so indignant that she did not bring the ointment directly to him.

Eighth, for those viewing these questions through the eyes of faith, the prophecy which Jesus offers about Mary’s anointing being proclaimed wherever the Gospel is preached throughout the world should not be ignored (see Matt 26:13; Mark 14:9). It is Mary Magdalene, not Mary of Bethany, who has been celebrated in the liturgy and litanies of Christendom for more than a millennium. If Jesus’s words mean anything, then surely this is a feather in the cap of the traditional view. Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany are one and the same, and so the extraordinary Medieval cult was a direct fulfillment of the prophetic words which Christ delivered at his second anointing.

None of the foregoing considerations constitute a knock-down argument, nor are they all of equal evidentiary weight. Taken cumulatively, however, they provide a convergence of probabilities that establishes the reasonableness of the traditional view. To identify the two Marys as one is to paint a consistent portrait across the four Gospels, unveiling a coherent character who continually shows herself to be at once impulsive yet contemplative, impassioned but devoted.

Reasons for Hiddenness

We must now turn to the one major objection that the traditional view faces, namely, if the two Marys are indeed the same, then why do the Gospel authors never assert this explicitly?

Here we should recall from the outset that the Scriptures often present us with veiled invitations to contemplation. Bountiful are the treasures that lie hidden beneath the surface, and the particular genres which the evangelists employ often leave layers of mystery and meaning designed to reward only the most attentive of readers.

Fr. Davidson makes the point shared by a number of figures in the tradition that there is a veil of secrecy that covers the way the evangelists treat the holy family of Bethany. On the testimony of John’s Gospel, we can infer that Mary, Martha, and Lazarus were among Jesus’s most cherished friends. Yet despite this, we are faced with some enormous oddities. Matthew and Mark never once mention the family of Bethany by name, for example, and in their anointing accounts they keep Mary’s identity anonymous.

Luke includes the famous scene of Martha serving while Mary sits at the feet of the Lord, but he pointedly avoids giving any background information on the two women, and he is careful not to disclose where the event takes place. That leaves us with John, who alone among the four evangelists takes the time to recount Jesus’s most politically decisive miracle (see John 11), who alone conveys how close this family was to Jesus, and who alone names Mary as the woman who anoints His feet.

Of course, the reasons may be manifold as to why evangelists include and omit the events they do. But we know that Mary Magdalene, as the first witness to the Resurrection, would have been high up on the list of political targets for the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem. It is therefore quite possible that for safety purposes the evangelists framed the identity of both the Magdalene and her Bethany relatives in deliberately mysterious terms.[9]

Another possible explanation for the lack of explicit identification is the ancient custom of preserving the reputation of prominent figures in the community.[10] Notice how Luke relates the story of Levi’s conversion in chapter 5 of his Gospel, and then includes him as Matthew within the list of apostles in the following chapter, without ever pausing to explain the name change. Luke seemingly did not want to draw attention to the fact that Matthew had formerly been a tax collector. It makes sense, then, that he could tell the story of the anonymous sinful woman in chapter 7 of his Gospel, and then re-introduce her as Mary Magdalene in chapter 8.[11]

More broadly, it is worth remembering that the Gospels’ usage of personal names can often appear confusing. Nathanael has always been recognized as another name for Bartholomew, for example, although this is never made explicit in Scripture. At times Peter is still called Simon even after his re-naming. Mary the wife of Clopas is identified in at least four different ways.[12]

Last but not least, we should recall that one of the central literary riddles of John’s Gospel is the figure of the beloved disciple, whose identity scholars continue to debate to this day. When one pauses to reflect on this fact, and to dwell more generally on the “show, don’t tell” methodology that so often characterizes the evangelists’ approach to conveying the mysteries, then it suddenly becomes more intelligible why they might frame the identity of the Magdalene in the way that they do.

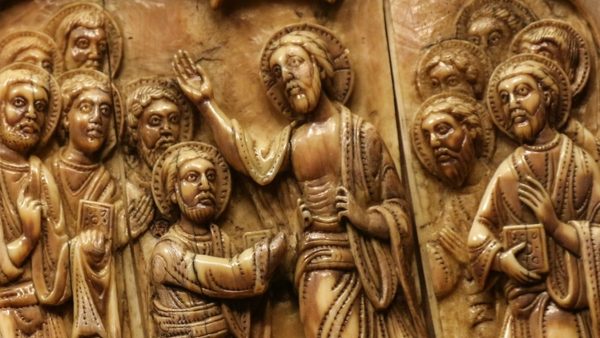

Here I have offered a preliminary argument in favor of the view that the traditional Western understanding of Mary Magdalene remains reasonable and defensible. On exegetical grounds, the convergence of the sinful woman of Luke 7 with Mary of Bethany appears highly likely, and the further identification of this individual with Mary Magdalene remains perfectly plausible. This view is corroborated by the lex orandi of over a thousand years of liturgical practice and artistic expression, together with the heartfelt testimony of many of history’s greatest mystics and saints.

Today, therefore, the traditional depiction of the Magdalene can no longer be regarded as a fringe scholarly position. On the contrary, a firm case remains to be made that the traditional position makes the best sense of the data. A major implication of this position is its ability to transform Mary Magdalene from being a mostly background figure in the Gospels, typically only mentioned in passing, to becoming one of the New Testament’s central heroines.

Thus retrieved, Mary Magdalene shines forth once more as the one who loved much (Luke 7:47), the one from whom seven demons were cast out (Luke 8:2), the one who grasped the one thing necessary (Luke 10:42), the one who moved the God-Man to tears (John 11:33–35), the one who did a beautiful thing for Him (Mark 14:6), the one whose deed would be proclaimed throughout the world (Mark 14:9), and the one who first saw the Risen Lord and believed (John 20:18).

In our broken world and hurting Church, she stands as a beacon of that supernatural hope which defined her spiritual journey. Time and again she shows us what it means to sit at the feet of our Lord—a motif that crops up in virtually every scene in which she appears. Bearing in her heart the wounds of love, this radiant heroine and fierce advocate of sinners reveals in an unparalleled way the depth and beauty of a life walked with Christ.

[2] For example, Tertullian, Gregory the Great, Augustine of Hippo, Bede the Venerable, Anselm of Canterbury, Thomas Aquinas, Catherine of Siena, Thomas More, John Fisher, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, Francis de Sales, Mary of Ágreda, Anne Catherine Emmerich, John Henry Newman, and Elizabeth of the Trinity were all were persuaded by the idea that there is more to Mary Magdalene than meets the eye. Such a litany of saints, scholars, and mystics cannot all be dismissed as mere simpletons toeing the party line. Even the arch-Reformer Martin Luther maintained the traditional view. Such a diverse group of thinkers may yet be mistaken, but they deserve a fair hearing.

[3] Matthew, Mark, and John’s accounts agree on all the important points of the story, such that we can be confident they are describing the same event. The only discrepancies arise in minor details, for which ready explanations are available.

[4] See Davidson, 32.

[5] Scholars who reject this approach are also confronted with the supreme oddity of Mary of Bethany falling off the map after chapter 12 of John’s Gospel, even as Mary Magdalene appears out of nowhere to suddenly claim pride of place at the foot of the Cross and occupy center stage in John’s Resurrection sequence.

[6] The mention of nard is especially significant here since the word is ever used in the anointing scene at Bethany (Mark 14:3; John 12:3) and in the Song of Songs (1:12; 4:13–14).

[7] Note that there is no confusion about whether this Mary might be Our Lady, since the evangelists are always careful to explicitly identify her as the mother of Jesus.

[8] Here the traditional view has an intuitive appeal with its conviction that the same Mary who sat contemplating “the one thing necessary” (Luke 10:42) would never countenance being separated from Jesus at the moment of his death.

[9] The earlier Gospels, in particular, seem more concerned with safeguarding the family of Bethany, whereas John, who writes later, is able to express things a little more clearly.

[10] Consider the decision of the synoptics to refrain from naming the apostle who cut off the servant’s ear in the garden of Gethsemane; it is not until the Fourth Gospel, written some time later, that we learn the culprit was St. Peter.

[11] Fr. Davidson adds the consideration that people in the ancient world were already criticizing Christianity for valuing the testimony of women too highly, hence the evangelists may not have wanted the first public witness of the Resurrection to be uncovered as a woman who used to have a very poor reputation.

[12] She is variously referred to as “the other Mary” (Matt 27:61), as Mary of Joses (Mark 15:47), as the mother of James (Mark 16:1), as the mother of James the Less and of Joseph (Mark 14:40), and as the wife of Clopas (John 19:25), who, incidentally, might also be known as Alphaeus (Matt 10:3).