SPOILER ALERT: This review does indeed contain spoilers.

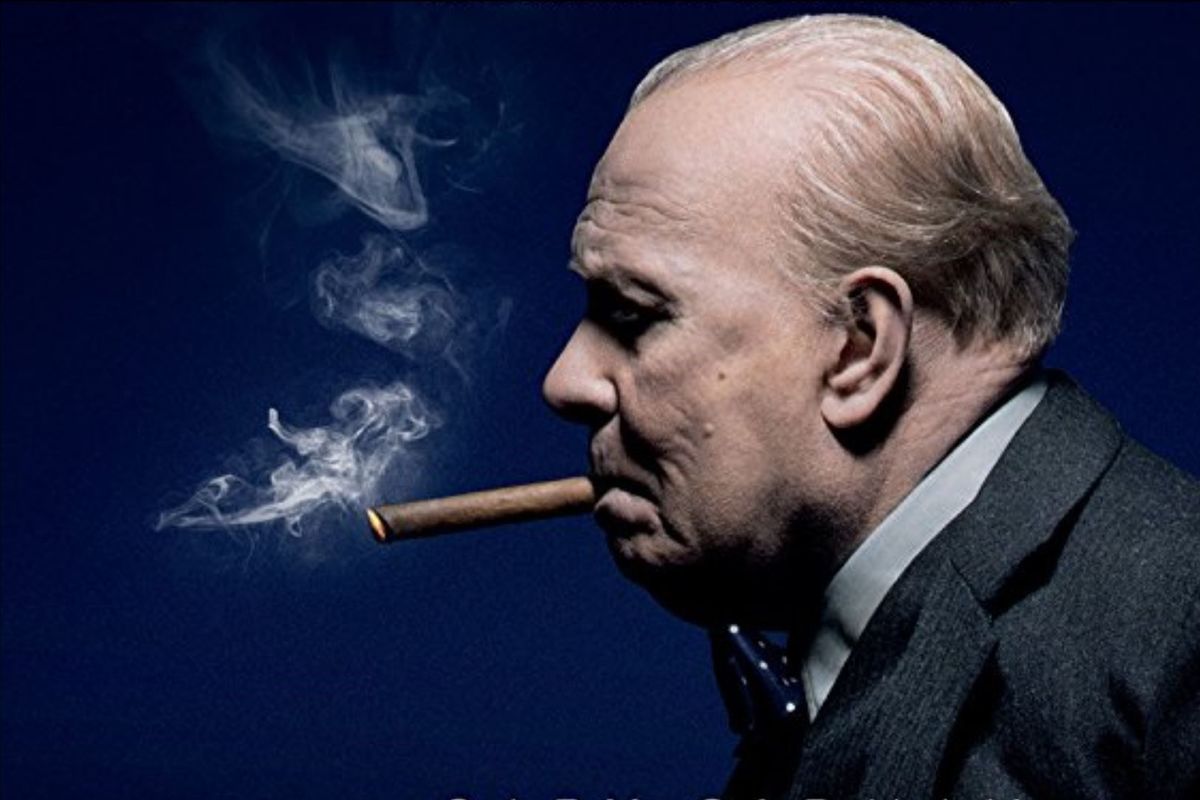

Darkest Hour is a compelling dramatization of the life of Prime Minister Winston Churchill during the time between the resignation of his predecessor, Neville Chamberlain (which coincided with the German invasion of Holland, Belgium, and France), and Churchill’s famous “We shall never surrender” speech to the House of Commons following the evacuation of the defeated British army at Dunkirk only a few weeks later. During this short period, the Allies experienced their worst defeat of World War II. However, the slow-motion disaster unfolding in France and the low countries is mostly in the background; the focus of the film is on Churchill, and his lonely struggle through Britain’s darkest hour.

That struggle may truly be said to be a spiritual one. From the beginning, Churchill must contend not only with the collapse of the Allied forces, but also with the mistrust of his king and growing opposition from his political colleagues, several of whom wish to give up the fight and negotiate a peace with Hitler. The film effectively evokes the atmosphere of despair which deepens over the British nation with each new misfortune and setback. As the days pass and conditions worsen, Churchill becomes more and more alone in his desire to keep fighting, mirroring Britain’s growing isolation as her allies fall one by one. His fervent determination to do what is right is severely tested by both outward opposition and inward doubt.

Sitting in the theater, I was reminded of a remark made by the minor devil Screwtape in C. S. Lewis’s eponymous book: “It is so hard for these creatures to persevere.” We know that the devil plays a long game. His goal is gradually to wear down the will and darken the heart—to make us forget God’s mercy and despair of improvement. He does this by leveraging the small sorrows in our daily lives and the heart-wrenching acts of evil in our world, combined with constant reminders of our own sins and imperfections. His aim is to increase the pressure until we lose our sense of why we are fighting and begin to desire some sort of compromise with evil.

Darkest Hour beautifully depicts the effects of this spiritual warfare. Churchill is an imperfect man. He drinks too much, smokes too much, is brusque, crude, opinionated, and has difficulty admitting fault. These personal faults and his previous failures confront him at every turn, cutting him off from others and feeding his doubts about whether he is worthy or even capable of the task that is before him. In one early scene, his self-absorbed rudeness drives his new secretary out of the room, weeping, after only five minutes. In a later one, challenged by a colleague, he mounts an unconvincing, blustering defense of the disastrous Gallipoli campaign in World War I, which he had masterminded.

For all this, Churchill still has the sterling qualities for which he is famed: good humor, determination, steadiness under fire, and a clear sense of what is at stake. He sees in Hitler’s Germany a threat to the whole of Western civilization and is unwilling to back down. As the pressure mounts, however, it becomes clear that his greatest enemy is isolation. He is almost entirely alone, and this knowledge bears down upon him with each new day. In what I found to be one of the most moving scenes in the whole film, the prime minister makes a midnight phone call to his friend, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and is reduced to begging for military aid, only to be rebuffed. In that moment, the frame expands, but there is only darkness around Churchill; he is alone in the dimly illuminated circle of a small lightbulb, abandoned by even his closest allies. That this is England’s position, too, is underlined by a poignant scene in which a slow, continuous pull back from the commander of the overwhelmed British garrison at Calais reveals the garrison’s isolation in a sea of darkness and explosions, just as German bombers appear overhead to deliver the coup de grâce.

Isolation is one of the great dangers of the spiritual life. In God, we know who we are and why we fight; left alone, we succumb to the lies we hear and find ourselves without hope. Fittingly, at Churchill’s lowest moment, it is the love and support of those closest to him that strengthens him to go on. His long-suffering wife, Clementine, is under no illusions about Winston’s faults, but her love and belief in him is unwavering. His young secretary is staunchly loyal and reminds him of the power that his voice still has has to win hearts and minds. Even the king, at first aloof, reaches out to comfort Churchill at his lowest ebb, offering friendship and support. It is in communion that Churchill is renewed; the intercession of others reminds him of his own value and gives him the strength to return to battle with a joyful heart.

At one point and only one do I think the movie stumbles slightly. It is this: not content that Churchill should be bolstered merely by the support of loved ones, the filmmakers depict him as being still despondent and on the verge of considering terms for peace, until an impulse to ride the London Underground leads to conversation with a group of ordinary Britons, who unanimously voice their desire to continue the fight. It is only once he has been fired by this encounter that Churchill returns to parliament, rallies support, and overcomes the machinations of his rebellious cabinet members. The problem I have with the Underground scene is not merely that it did not actually happen in real life (Churchill apparently only rode the Tube once in his entire life, during the General Strike of 1926), but that it invents a highly implausible situation that diminishes the greatness of the character.

The real-life Churchill’s determination never wavered to the point that he seriously considered peace talks, and the sad truth is that had he ventured onto a train in May of 1940 he would have encountered a population largely neutral towards the idea of a mediated peace with Germany. It is to Churchill’s everlasting credit that he refused to compromise in that darkest hour and instead rallied the British people to continue fighting by his determination and rhetoric; a scene suggesting the exact opposite is unnecessary for the story of the film and in my opinion does an injustice to the man.

This historical inaccuracy aside, as a whole, Darkest Hour is a stirring, heartwarming film, with much to stir the soul and enliven the heart. Though probably not the intention of the filmmakers, it serves admirably as a true-life account of spiritual fortitude.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LtJ60u7SUSw