1. What Is Mercy?

The quality of mercy is not strained;

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:

'T is mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The throned monarch better than his crown:

His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty,

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptred sway;

It is enthronèd in the hearts of kings,

It is an attribute to God himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God's

When mercy seasons justice.

—Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene 1

Aquinas gives two definitions of mercy in the Summa Theologica. Here is the first one:

Someone is called merciful (misericors) because he has a sorrowful heart (miserum cor) since he is affected with sorrow by another’s misery. From this it follows that he works to take away the misery of the other as if it were his own, and this is the effect of mercy. To sorrow, therefore, over the misery of another does not belong to God, but to take away misery does belong most properly to God, if we understand by misery, any kind of deficiency. Defects are not taken away except by some perfection of goodness [being given], but God is the first origin of goodness (ST I 21.3).

The first feature of mercy is to feel sorrow over another’s misery; this cannot belong to God as an emotion since he has no passions. Yet, human suffering is displeasing to his will since he loves everything he has made. Scripture often describes his merciful love by the analogy of human compassion, as in Hosea 11:

When Israel was a child, I loved him,

and out of Egypt I called my son . . .. . . How can I give you up, O E′phraim! . . .

. . . My heart recoils within me,

my compassion grows warm and tender.

I will not execute my fierce anger,

I will not again destroy E′phraim;

for I am God and not man,

the Holy One in your midst . . .

The second feature is to take away the misery by some act. This belongs supremely to God since misery is taken away by giving some good and God is the first source of all that is good. Article four extends the second feature of mercy from the removal of misery to the removal of any deficiency:

Mercy and truth are necessarily found in every work of God if mercy is taken for the removal of any deficiency whatsoever; although not every deficiency is properly called misery, but only a deficiency in a rational nature which can be happy; since misery is opposed to happiness (ST I 21.4).

Mercy in the broadest sense is the removal of any lack at all, if the act is gratuitous. Otherwise it would be an act of justice and not mercy. To pay a debt is not merciful, but just.

2. Why Is Mercy “Mightiest in the Mightiest?”

Mercy is the highest virtue, St. Thomas tells us, because it is the virtue of the “superior precisely as superior.”[1]

In itself indeed mercy is the highest, for it pertains to mercy that it flows to the other, and what is more, that it makes up for the defects of the other; and this belongs most to the superior. Hence to be merciful is said to be proper to God, and in it his omnipotence is especially made manifest (ST II-II 30.4).

It is because God has all the riches of being and infinite joy in himself that he gives a share of his riches to creatures and that giving of his wealth manifests his power the most.

3. How Is Mercy an Attribute of God?

It is an attribute of God, because, as De Koninck puts it, it is the “universal root” of all God’s external acts; it is the beginning of everything God does for creatures. “Mercy, having the meaning of absolute universal root, extends from one end of the universe to the other.”[2] God always wills his own goodness therefore God’s goodness is the final cause of all that God does (ST I 19.2). But every act by which God shares his goodness with creatures is merciful including creation. God could love his own goodness eternally without ever creating.

We must go back to the primary motive and to the universal way of God’s communication without—ad extra. But this motive is nothing other than the divine goodness insofar as it is diffusive of itself. The root of the primary way of this diffusing and of this manifestation outside is mercy, “All the ways of the Lord are mercy and truth” (Psalm 24:10). That is why St. Bernard calls the mercy of God causalissima causarum—of causes the one that is most cause.[3] Mercy is the first root, even of justice.[4]

Mercy is the deepest reason for all that God does outside himself. Mercy is the connection between gift-of-self within the Trinity and gift-of-self toward creation. It is because God’s goodness communicates itself in the Trinitarian processions that he communicates his goodness outside to creatures. As Aristotle says, “What is prior must be the cause of the later terms.”[5] Or as St. Thomas says, “the processions of the [divine persons] are the patterns for the production of creatures (ST I 45.6). The Creation, Incarnation, and Redemption are all willed for the sake of manifesting God’s glory, by way of mercy and justice.

“Mercy is the first root, even of justice.”[6] Justice follows mercy, because justice is giving to each its due, but nothing can be owed anything until it exists. Thus, existence itself is purely the gift of mercy; nothing can earn its existence. St. Thomas says,

Mercy can be said according as any deficiency whatever is taken away; and thus in the work of creation there is mercy: because God, by creating, removes the greatest deficiency, namely not to be; and this he does out of a willing favor, not constrained by any debt.[7]

As the first cause of every act of God toward creatures, mercy is also the most powerful cause; mercy operates more strongly to produce every effect of God than any other cause. St. Thomas says, “So it is that mercy shows up in any work of God . . . And its power is preserved in everything consequent upon it, and even operates more strongly in it, as the primary cause flows in more powerfully than the secondary cause” (ST I 21.4).

Not only is mercy the cause of every act of God towards creatures, but it is also the cause of the disproportionate goodness of acts of justice. St. Thomas says, “Because of this [power of mercy], even in those things that are owed to creatures, God, out of the abundance of his mercy, gives more generously to creatures than is proportionate to their needs” (ST I 21.4). One might even say that there is a kind of foolishness or extravagance to mercy that pays the last workers the same as the first (Matt 20:1-16).

4. What Is the Measure of God's Mercy?

There are many levels of divine mercy; mercy is the greatest when it lifts what is lowest to the highest degree. De Koninck says:

If mercy is fulfilled in the elevation of the inferior, this elevation will be the more merciful and revealing of the divine goodness and omnipotence when it raises up that which is most inferior. In other words, we can judge the measure in which God has willed to manifest himself by the degree of merciful raising up that He has chosen to realize.[8]

Mercy is also greater when the superior stoops down more deeply and identifies himself more fully with the deficiency of the inferior. It reaches its fullest intensity when the superior bears the misery of the inferior for the inferior’s sake.

In the Incarnation, God lifts what is low, a man, to the highest degree, divinity. “This same Son arises from two extremes of the universe, reuniting our baseness with his supreme grandeur.”[9] But what is elevation to divinity for a man is at the same time descent to humanity for God. God could have given us supernatural life immediately as he did to the angels. Instead, De Koninck tells us, God chose to accomplish this elevation “in a much more striking manner”[10] through humbling himself by assuming a limited created nature:

Descending thus into his creation in order to elevate it from within to the properly divine order, God would already manifest the mercy of his omnipotence in an infinitely greater measure than in the creation alone of intellectual creatures so perfect in themselves or in their immediate elevation [like in the angels].[11]

De Koninck calls this entering into creation a descent because God the Son, who contains the fullness of being, assumes what is limited and empty, a created nature, in the unity of his person. “Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant” (Phil 2:5-6). This descent reveals his mercy more than creation because it is a greater bending down to his creation.

Furthermore, Christ assumed not just the lowest possible intellectual nature, but a fallen human nature, liable to suffering and death to be more merciful to us. Someone who is merciful, De Koninck writes, “takes on himself the misery of another as if he made it his own.”[12] This can be done in two ways: by “affective union,” or by “real union.”[13] In an “affective union,” we suffer in sympathy with the pain of the pitied one as though it were our own pain. When a friend suffers a tragic loss from the death of a child, we suffer with our friend without losing our own child. The more we love our friend, the more closely we identify his or her loss with our own and the more we suffer.

In a “real union” we choose to suffer the very same pain in our body as the pitied one. For example, St. Damian chose a real union with the lepers of Molokai; he chose to suffer the same island isolation, meager diet, diseased and criminal company, and finally the leprosy itself of those whom he pitied. He wrote to his brother, “I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ. That is why, in preaching, I say ‘we lepers’ not ‘my brethren.”[14] When he discovered he had contracted leprosy, he wrote to his Superior, “I am a leper. Blessed be the good God!”[15] St. Damien could choose to suffer with the lepers because he was a man like them. He could take a boat to their island and live in a hut like theirs; he could suffer from hunger and cold; he had a body like theirs that could contract their disease of leprosy and die.

God cannot suffer by such a real union with us since he has no body that could suffer bodily harm or death. How could the Author of Life die? Yet, he chose to do so by the most remarkable invention of his love, the Incarnation. But God has assumed human nature along with its passibility, thus taking on our misery in the manner that it affects us, that is, physically assuming evil (malum poenae) in this way—a darkness far more profound than any that comes from our nature, the most profound that God could assume.[16]

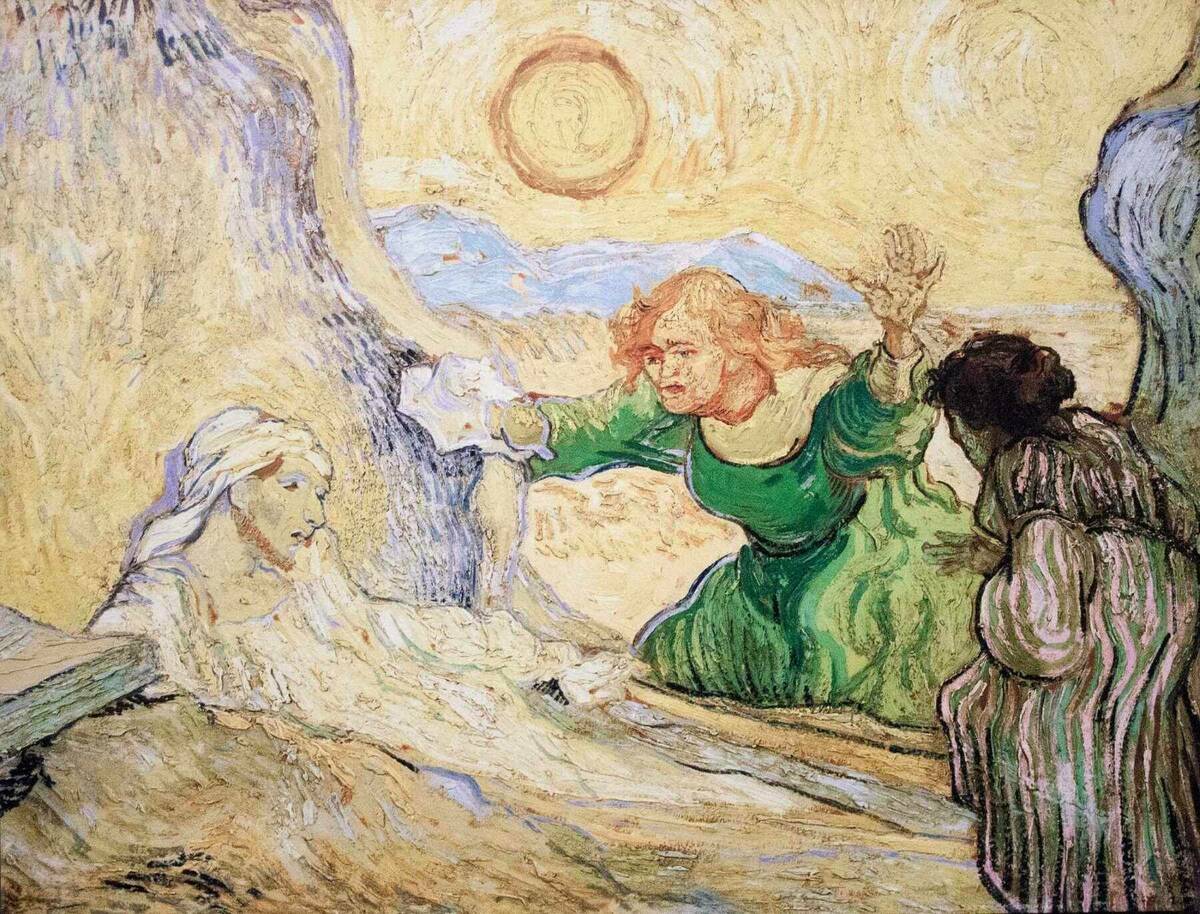

The Son has assumed our nature in its fallen state to suffer all that we suffer. “The merciful one takes on himself the misery of another as if he made it his own.”[17] God took our misery both by an affective union and a real union.[18] God has mercy on us first by an “affective union;” He sympathizes with our pain by his Sacred Heart, a human heart that becomes the instrument for his divinity. Jesus cried over the fate of Jerusalem; he wept at Lazarus’s death. He had pity on the crowd because they were like sheep without a shepherd. Christ can suffer what Hosea showed us of the depth of God’s love for us.

The assumed human nature also allows him to suffer by a “real union.” He bears our sufferings in his own body and soul. He can choose to suffer tiredness, hunger, thirst, scourging, and even death because he now has a body like ours that can suffer and die. Since humans are the only intellectual beings that are bodies, only humans can suffer physically and die. If God had assumed an angelic nature, he could not have suffered physical pain and died for us. It is man’s poverty that allows God to show more mercy to him than to the angels; God can stoop lower by taking on a passible human nature.

5. Why Is the Cross the Most Profound Act of God’s Mercy?

Christ’s passion and death are the ultimate divine humiliation and the ultimate revelation of divine mercy. At the death of Jesus, the veil to the Holy of Holies was ripped open because the innermost heart of God was revealed (Luke 23:34). Given the immensity of mercy that the Almighty has chosen to manifest, it is only fitting that the universal royalty of Christ and of his mother was manifested in the Passion. “Pilate then said to him, ‘You are a king?’ Jesus replied: ‘You have said it, I am a king’” (John 18:37). It is in the Passion that shines forth in all its profundity and extent the allegorical meaning of “I am black but beautiful” (Song 1:5).

Christ affirms his kingship in the Passion because, paradoxically, it is there above all that his majesty is revealed. He is omnipotence, but his power is revealed in his mercy. Jesus is black because he is suffering the blackest misery for our sins; he is beautiful because he is thereby earning our redemption and showing his great love for us. “He loved them to the end.” (John 13:1).

De Koninck writes that God’s reveals his omnipotence the most when he suffers evil for us and turns it to our good, because evil is what is most directly opposed to God. To turn evil to good is to be all-powerful. Only the creator of all being can “rescue” evil from its non-being or even anti-being and opposition to God and use it to cause a recreation of all being in Christ, a new heaven, and a new earth. De Koninck explains the divine manifestation of mercy in Christ’s death as follows.

Sin is not just any defect: it is that which is at the farthest remove from God. Properly speaking, evil is not a simple privation, it is opposed to the good as a contrary. Consequently, the mercy which will face down evil, which will be victorious over it, will also be, in a sense, the greatest possible. The manifestation of the divine omnipotence will be, here, in the universe itself, like a return on itself: it will be the fullness of mercy. Evil (malum poenae) is ordered to the greatest manifestation of mercy that could be conceived. O felix culpa quae talem ac tantum meruit habere Redemptorem!—O happy fault that merited for us to have such and so great a Redeemer![19]

Evil is allowed to exist because of mercy. It is the occasion of the greatest revelation of God’s mercy, the Cross. As De Koninck says, God the Son “faces down evil” and conquers it through his gift-of-self on the cross. “I lay down my life for the sheep” (John 10:15). This humiliation “even to death on the cross” is so great that it reveals the infinite mercy of God; it returns the outermost limits of creation, the reign of evil, to God. It reveals the Son’s divinity by revealing his immense mercy. “When you have lifted up the Son of Man, then you will know that I am” (Jn 8:28). Mercy is truly “mightiest in the mightiest.”

[1] Ego Sapientia, 22.

[2] Ego Sapientia, 22.

[3] St. Bernard, In antiphonam Salve Regina, sermo 1, n.3 (t.7, p. 43a).

[4] Ego Sapientia, 21..

[5] Aristotle, Metaphysics II, 2 (994a.12).

[6] Ego Sapientia, 21.

[7] Scriptum super Sententiis IV, 46 q.2 a.2 qc. 2 ad 1.

[8] Ego Sapientia, 23.

[9] Ibid., 27.

[10] Ibid., 26.

[11] Ibid., 26.

[12] Ibid., 34. De Koninck is closely following the doctrine of St. Thomas. ST II-II 30.2.

[13] Ibid., 34.

[14] Blessed Damien Molokai, Letter to his brother in 1873, Catholic Dictionary-Damien Father (Apostle of Lepers) dictionary.editme.com/Damien.

[15] Blessed Damien Molokai, Letter to his superior, October 1885, Catholic Dictionary-Damien Father (Apostle of Lepers) dictionary.editme.com/Damien.

[16] Ego Sapientia, 34.

[17] Ibid., 34.

[18] Ibid., 34.

[19] Ego Sapientia, 33.