I invite you to give thought to a rather surprising statement that Thomas Aquinas makes toward the beginning of his Summa theologiae. For some it might even be disturbing, and I too was a little taken aback when I first discovered him saying that “[even] by the revelation of grace we do not know what God is; and so it is that [by grace] we are joined to [God] as to one unknown [to us].” He does not say, “God is hard to know, you have to work at it,” or “God is elusive” or “evasive,” but simply: what God is, what kind of thing God is, is unknown to us, even by faith.

It is true that the full text of the passage provides context and an important qualification, a qualification that I shall come to in due course. But as it stands—and despite that qualification Thomas does let it stand— by any measure it is a startlingly agnostic statement. I imagine it would be less shocking to modern theological minds had Thomas said only that God’s nature is unknown to us by way of our theologically limited powers of natural reason. That, after all, is a proposition that a modern theologian in the spirit of Karl Barth would have been only too pleased to endorse, had Thomas allowed that if not by reason then by faith God’s nature is made known to us. But that is not what Thomas says. He says that God’s nature is unknown to us even within the revelation of grace.

We Do Not Know What God Is

Ever the deadpan writer and teacher even (or perhaps especially) when at his most theologically radical, Thomas tells us this in an article of the Summa in which he asks whether grace affords us a higher knowledge of God than that which can be had by our natural, unaided powers of reason. In the dialectical manner that he employs for such discussions, Thomas first addresses the view to which in due course he will say he is opposed. He asks: Is there not a case to be made for the view that the revelation of grace gets us no further into the knowledge of God than does the reach of reason alone? You might reasonably have thought you could guess where Thomas would go with this: he will say, you imagined, that of course the grace of faith draws us further into the knowledge of God than reason by its own powers can. But he doesn’t say this, not yet, he wants to hold back a minute, for there are powerful objections to any such proposition, one of them supplied by the 5th century Syrian monk known today as the pseudo-Denys, who tells us that though what in this life unites us best to God is grace, still even by grace we are made one with God as to a being whose nature, he says, is omnino ignota, “altogether unknown,” to us. Hence, the grace of revelation gains no better traction on God than what bare reason anyway affords us: in either case we are left in the dark as to what God is, we are wandering as it were without intellectual bearings, lost in a cloud of unknowing.

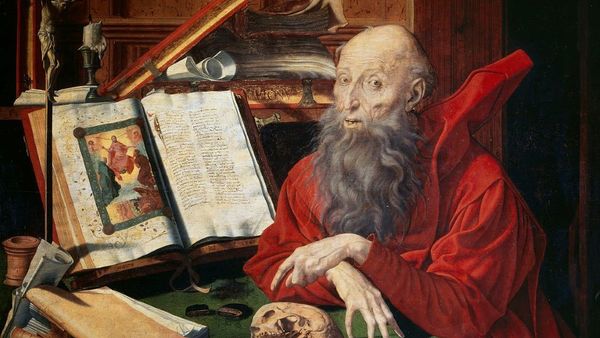

But that is not all, Thomas adds, for it is on scripture, on the witness of Moses no less, that the pseudo-Denys relies when he so emphatically teaches of this God beyond all knowing—Thomas doesn’t say exactly where scripture records this, but doubtless he is thinking here, as elsewhere he says he is, of the great epiphany recorded in Exodus 33:17– 23. There we are told that, having ascended to the summit of Mount Sinai shrouded in a cloud of unknowing, Moses is instructed by Yahweh to hide himself in the cleft of a rock so as not to see the Lord’s face when he passes by. For seeing the face of God is dangerous, you need to be dead and under special conditions of God-given vision thereafter, which is why while you are alive the face of God would kill you were you to be exposed to it. For “no one may see my face and live.”

This is strong stuff open to no qualification, and most theologians seem not to take it all that seriously, supposing that “negative theology” is some sort of spiritual fashion statement, splendidly dramatic but optional, a preference for those of an austere taste in matters epistemological. Many do seem to think that once you get the hang of theological talk, then, if not by way of reason, maybe from the Bible, and certainly in Christ, God is as routinely knowable in, say, the practices of Christian worship as “the man in the street along.” But Thomas will not have it so. The weight of biblical authority exerts heavy pressure on claims to such cheap and easily acquired knowledge of God: before the transcendence of God faith is every bit as benighted as is reason, and Thomas is going to have to make concessions to that biblical authority. And so he does. Let us first yield to the authority of Exodus, he says, and then to that of the pseudo-Denys, who, along with most of his fellow theologians of his time Thomas regarded as possessing an authority only a little less than the Bible’s; and let us accept what it tells us, howsoever severely economical it may epistemologically seem—for that statement, he says, stands, come what may. Having said which he then puzzlingly would seem to say the contrary, adding that by grace “we do know [God] more fully insofar as [by grace] we are shown more of his effects and higher ones; and that is so inasmuch as on the basis of revelation we make some attributions of [God] of a kind unavailable to reason, such as that God is three and one.”

The whole passage—it’s all in a tiny response to an objection—now stands before us, and it is hard to make out where the consistency lies. The bold and unqualified agnostic statement emphatically reaffirmed as it stands is supplemented by a qualification tacked on to it that seems to contradict it. In particular it is puzzling in that it might seem to amount both to affirming something, namely that we do not know what God is, and then, scarcely a breath taken, to denying it with an implied “nonetheless.” “Nonetheless,” Thomas says, God is known better by faith than by reason. Well then, one or the other, either we do know God, what he is, or we don’t. If we know God better by faith and somehow less well by reason, then implied is the proposition that even by reason we do know at least something about what God is, even if not very much. And that doesn’t seem to fit with the bald statement with which the passage begins: whether by reason or by faith we do not know what God is, God’s nature is to us omnino ignota. The argument is evidently in need of some clarification. So let us try to clarify.

Let us allow the agnostic statement to stand: we do not know what God is. Whatever else he is going on to say, Thomas holds on to that proposition, and you can get his drift along some such lines as this. We human beings are worldly creatures, we are, after all, animals, environmentally locked into a material ecosystem with which, by way of our essential embodiment, we are finely calibrated: we need an environmental temperature sustained within strict limits, and we are, as we all now know, worryingly close to them. In that universe of experience, in the material world to which our lives, and our minds, are thus naturally attuned, we can get to know any individual thing with which our senses acquaint us in its distinct individuality—this tree, this person, my wife, or each one of you—only under some description of the kind of thing that each one of us is an individual instance of. I cannot know just “this individual, whatever-it-is doesn’t matter.” I can know only this individual who is this person, or this woman, or this lump of wood that is this tree. That is, individuals fall under descriptions, they come in kinds, the “this” depends on the “what,” for I can experience this individual only insofar as I find a particular place for it within a worldly context of meaning, within an ecology, or, as we say, an environment.

Such thoughts are worth giving time and space to in an individualist culture such as ours, for which what is primary, and from an explanatory point of view the more fundamental—or even on some accounts, also from an existential point of view more basic—is a pure abstraction known as “the individual.” As Herbert McCabe used to say, maybe for a modern mind in the West it seems intuitive that societies are made of individuals; but it isn’t intuitive at all, it’s the construction of a theory that has become the truism of a culture, a bit of ideology that, until the emergence of a nominalist and in consequence an individualist culture in the late medieval and early modern periods, no patristic or early medieval theologian would have found convincing. At any rate for Thomas the prior truth is the opposite, namely that individuals are made of the social relations in which they are born, grow, learn to speak, have sex, give birth, love, and die, and therein is the paradox of modernity: it takes a certain form of society to make its individualism seem intuitively obvious; and once you see that “the individual” is a social construct you can see that there is no prior individualist intuition there anyway, but only a socially acquired moral and ideological preference. An ontological individualism according to which the basic and irreducible existent is “the individual” is as much a social construction as any other, and a more counterintuitively constructed abstraction than many.

This thought may itself seem a bit abstract, but in truth it is simple. I love my wife. I love her in her individuality of course, but just as obviously I love her in her individual womanhood, so that how I love her individually will depend in part upon how far I successfully grasp her construction of that womanhood. Of course I love her for who she is, but it won’t be her I love if I do not love her for what she is—that knowledge and love of who inextricably tied in with the what, the two together. That’s just how we love.

When therefore Jews, Christians, and Muslims say, as they all do, that there is “but one God,” the ultimate and complete object of our knowledge and love, they immediately cause themselves a problem precisely arising from this insistence that they do not know what God is. They say that they are commanded to love God, or as Thomas says, to be united with him, not knowing what they love. So how can they know how to love? For if there is no knowable kind of thing that God is, then it would seem to follow that in the case of God you cannot get the distinction to work between what God is and who God is so as to love the “who.” For there is no kind of thing, Thomas says, of which the one God is the only instance. And if that is so we are compelled to wonder what meaning can be rescued of the word one as designating “this” God, the God of any of the Abrahamic faiths, Jewish, Christian, or Muslim.

To be sure, Thomas cannot find himself going down the line of supposing that Jewish or Muslim insistence on the oneness of God is somehow less mysterious than the Christian insistence on the Trinitarian threeness. The truth is, Thomas says, that whether by God’s oneness or by God’s threeness we are equally benighted, dumfounded, drawn into that cloud of unknowing that sits for ever on the summit of Mount Sinai where God dwells. For if we can say for certain that there is only one God, it is also true that we have lost track of the meaning of the word one in so saying. In that case, how should we love God? asks another Dominican—indeed, how could we love so unknowable a God? And that other Dominican replies:

You should love God unspiritually You should love him as a non-God, a nonspirit, a nonperson, a nonimage, but as he is a pure unmixed bright One, separated from all duality; and in that One we should eternally sink down, out of “something” into “nothing.” May God help us to that. Amen.

That Dominican of course is not Thomas. It is Meister Eckhart writing some forty years or so after Thomas’s death. It is not how Thomas himself ultimately concludes, as will see. But it is a pretty accurate statement of where Thomas is at the end of question 3 of the first part of Summa. For there he says that you should not suppose even the arguments that show God to exist to have got us anywhere near knowing what God is: the hopes for such knowledge are vain and must be quickly and firmly disappointed. And in a truly magnificent act of theological self-denial, one that should put to shame the uncritical theological optimists of our times, Thomas affirms in his deadpan academic manner exactly what Eckhart says in his rolling homiletic rhetoric: “Since it is not possible to know of God what he is, we cannot give thought to the manner of God’s existence, but only to how God is not.”

How Then We Do Know That God Is?

As I say, all this can come as a bit of a surprise for believers, even as a shock, for it would seem to push God away as a being wholly remote, inaccessible to all human experience, hardly the God they say they come to know in the intimacy of the person of Christ. And anyway many will wonder, very reasonably, how Thomas can say that we do not know what God is consistently with also saying, as he does at the very beginning of the Summa, that we can by means of five strategies of demonstration prove God’s existence. And, what would seem more problematic still, Thomas says that we can prove God’s existence without any appeal to faith or revelation or to anything other than plain secular reason. But how can this be?

The case for saying that God’s existence can be proved—“Deum esse probari potest,” he says—would seem to sit ill with not knowing what God is. Eat your cake—God’s nature is unknowable—if you must; but if so, how can you also have it if, consistently with God’s nature being beyond our ken, you can nonetheless rationally prove God’s existence?

The dilemma, thus somewhat oversimplified, causes some today to hold fast to one horn of it at the expense of the other. In fact, for some decades there seems to have been agreement among a majority of readers of the Summa that Thomas could not have really meant it when he said that his five ways are knockdown arguments, valid and sound, proving God’s existence on purely rational grounds. He simply must have meant something logically weaker than “rationally proved,” for a proof of God’s existence that was purely rational would reduce God to the standing of just another item in the universe, making a God out of a creature, or a creature out of God. That would certainly be idolatrous, and such an argument would do the opposite of rationally proving the existence of God. It would, rather more simply, make a God out of rational proof. And at once, having seen that, you begin to see how close the early 19th century atheist Ludwig Feuerbach cut to the Christian bone when he said that all the atheist has to do to defeat the Christian argument for God is to turn it upside down. Such arguments prove human reason to be subjectively godlike and infinite; they do not, as such theists suppose, prove that reason shows there to be an infinite being objectively divine. The logic here is common ground between the Feuerbachian atheist and the antirationalist theist: the God that reason can prove to exist is contained within the limits of the reason that constructs the proof. A God of the proofs is simply not God at all.

I am unconvinced. You can easily turn this argument on its head: only suppose you could prove the existence of God, an unknowable God whose nature is altogether beyond our power of understanding, omnino ignota, as the pseudo-Denys said; would that not show something about reason, namely that a rational proof is not after all a limitation imposed on God? Rather would it not show the opposite, that is, that reason, pushed all the way along its trajectory of questioning and explaining the world, breaks out on the other side of its limits into the boundless mystery of an unknowable God? The notion that reason, at any rate in its speculative and inferential mode, can operate only within a finite circle, forming an arc that endlessly returns upon itself, thus to enclose in its finitude all that falls within its remit, seems wrongly to explain what Thomas means by the word. It is certainly an idea of reason that is recognizable in much Enlightenment thinking. It is there in Kant. But it is nowhere to be found in Thomas.

For, as Thomas understands it, reason’s trajectory is neither circular nor in any other way closed: or, if it has the character of the circular in any way at all, it is as spirals are circular, a circularity that is also extruded out into an open and unending linearity. For, as the pseudo-Denys says, theology proceeds neither in a circle nor in a straight line only, but most distinctively in that combination of both at once, which is the spiral with neither beginning nor end. Therefore, just as Thomas asserts the demonstrability of God’s existence so also does he make himself quite clear: by way of those proofs our minds are opened up to something altogether beyond our comprehension, and it is that incomprehensible “something” which, Thomas says with characteristic brevity, “all people call by the name of God.” It is far from it being the case, then, as some have seemed to suppose, that the five ways draw God back into the closed circle of reason. They do exactly the opposite: they show, Thomas thinks, that reason itself, by way of its own characteristic exercise of proof, breaks through its own comfort zone and enters into the mystery of the Godhead, which lies entirely beyond its own limits. Thus do the apophatic biblical instincts of Exodus and Isaiah converge with the result of rational argument upon the one mystery of God.

Reason, then, Thomas says, is, in its culminating theological act, self- dissolving; it meets its own apotheosis by, as Hegel put it, abolishing itself in its very act of self-realization. And in that self-dissolution it leads us into that dark mystery that is God. It is just on that account that Thomas shuts the door so firmly on any kind of know-all theology, or, as we should say in a more biblical manner of speech, any form of idolatry. In particular it shuts the door on a God, as Immanuel Kant was centuries later to put it, “within the bounds of reason.” For Thomas, the proofs of the existence of God show that at the end of the line, there escaping the grip of reason, is ungraspable mystery: what most exists, that which sustains all other realities in existence, is unknowable. And then one needs to add, as Thomas will go on to show, that the mystery has a name: the true name of that mystery is “love.”

Faith and the Darkness of God

What, then, of faith? Here too Thomas might seem to be caught in a dilemma parallel to that in which it seemed reason was entangled, as if again he was attempting to have it both ways at once. For having said not only that reason must fail of the knowledge of God’s nature but that faith does so too, nonetheless he goes on to say that somehow faith supplies some knowledge of God that to reason is denied. And in a certain sense that is true, but not the obvious sense. For it transpires that what Thomas means is that faith does not dispel the darkness of God, for on the contrary, in faith one enters more deeply into that darkness, not escaping it, not dispelling it, but intensifying it. It is not after all very difficult to see what he is getting at in so saying, for if it is a paradox it is a paradox with a parallel in common, secular experience. Of course every human person is a mystery in herself, and no matter whom I observe in the bus or at the railway station or in the street I know that much about them, for their being a mystery simply goes with the fact of their being persons. I know that each person is a mystery to someone. But as to your life partner, the years of your intimacy with her will but draw you ever deeper into that heady unknowing which is love, a love that is not therefore a failure of knowledge but rather a knowledge which, born of a love in a common life shared, also allows her always to exist beyond her lover’s grasp, not possessed but free and unconstrained, as only lovers are to one another, in an intimacy and objectivity perfectly aligned. That, Thomas says, is the way in which through faith we know more of God than reason knows.

And that is why, Thomas says, it is through faith that we know the Trinity, of which by reason we can never know, even if by reason we can know that God is one. Is the doctrine of the Trinity, known by faith, grounded in more information about God, information of the sort you might have gained about people passing by in the street when you have checked out the statistics: that woman is black, so her income is predictably 20% or more below that of the white man next to her in the same job, and she is likely to feel oppressed by an unjust disparity? Not so: the doctrine of the Trinity is not a bit of additional information about God, additional, that is, to what we can know of God by reason. Faith doesn’t add something else to our rationally acquired knowledge of God.

It deepens it. It doesn’t help one understand this relation between reason and faith to make out the distinction, as did some theologians in the late Middle Ages—and most do to this day—to be that between a detached, objective, dispassionate, and uninvolved reason, contrasted with what was called an intellectus amoris, “love’s understanding” acquired in faith. William of St. Thierry had said in the 12th century that “amor ipse intellectus est,” love is its own manner of knowing, of which intellect knows nothing, and today there are many who likewise are tempted to follow down that sort of line as a way of distinguishing between reason and faith. In fact one of Thomas’s own students, Giles of Rome, yields to the temptation, saying that there is the contemplation of God, typical of the philosophers, which is of detached intellect, uninvolved and objective, and that it contrasts with the higher knowledge of the theologians, which “is more a matter of experience than of wisdom’s expertise; and it consists more in loving and in sweetness than in philosophical contemplation.” But in advance Thomas the teacher had already firmly slapped the temptation down to which his student Giles yields, not because he thinks that all knowledge worth having is dispassionate and objectively cold and detached, exercised as we say in a “brown study,” but for the opposite reason, namely that for him none is. Thomas thinks of intellect, even of reason unaided by faith, as a hot passion that seeks out the truth with intensity. He is after all a Dominican whose motto is Veritas, Truth, which Dominicans connected in their persons with “the way” and “the life,” as did the Lord they followed. Besides, Thomas’s Latin word studium means nothing like our modern English word “study.” Thomas’s studium means the intense and insatiable desire for knowledge and wisdom, it denotes a passion; our word study is closer to denoting the uninspired dispassion, at its worst, of the pedant.

That said, anyone who has tried reading the first part of the Summa theologiae, questions 27 through 43 on the theology of the Trinity, might seem to be justifiably skeptical: those questions are replete with technical distinctions between persons, properties, relations, appropriations, and processions, and with complex mappings of all these upon one another in ways that in their conceptual complexity set them well outside the intellectual range of any but a hard-nosed specialist with a very high IQ. Brown indeed is the hue of those Trinitarian discussions in the Summa. And yet the doctrine of the Trinity is at the center of the Christian faith and practice. How so?

The French Catholic existentialist Gabriel Marcel once said that one should never confuse a mystery with a problem. A problem asks for a solution, a solution that resolves the problem; and if you are bright enough, or conduct enough research, or consult those who know, you will find the solution to it, like the solution to a quadratic equation: once solved, the problem is laid to rest. But mysteries do not yield to investigation, argument, proof, or categorization. Mysteries can never be solved. They cannot be gotten to go away. Indeed, the deeper you enter into a mystery, the deeper the mystery gets. The gap between where you are with it and where the mystery lies never decreases, it only ever increases; nor can you think your way out of a mystery, for to do so is to reduce the mystery to the standing of a problem. But if you cannot think your way out of a mystery you can pray your way into one. Indeed, prayer is the only way there is into a mystery. Before a true mystery, the mind can only give way. You can’t crack it, you can only surrender to it, and the mind boggles—you bow before it and you say, humbly, “Amen.” For, strangely, in finding your way into a mystery you come to know it in a manner that no solution to a problem ever achieves. You know a mystery and you love it as you know and love a friend, you want to live with it: you can even, if you are a medieval monk or nun reading the Song of Songs, want to be kissed by it and make love together with it. Problems, by contrast, are a curse until they are dissolved.

So it is with the mystery of the Trinity. And that is why, if upon reading that first part of the Summa on the Trinity you might understandably feel constrained to complain that it makes the fatal mistake of reducing the mystery of the Trinity to an agenda of problems you can crack, it would be a mistake to think that way. For you would be right to suppose that Thomas there constructs a technical apparatus governing how to think about the mystery of the Trinity insofar as you can—or, perhaps better, that what he offers is a structure of reflection that will enable you to avoid making obvious theological mistakes of a kind that could lead you in no time at all into dogmatic error.

Generally speaking, I am sure that G. K. Chesterton is right: it is not the likes of Thomas but the heretics who want to reduce the mysteries to problems, as, for example, Arianism does. It is after all so much easier to suppose that Christ was nothing but a man anyway, and so that he “once was not” (as the Arians would have it), than to suppose that the eternal Word of God became a man: Arius in fact didn’t even want a problem to stand in his way of understanding Christ, never mind a mystery. And you could say that all that dry-as-dust apparatus of distinction and relation in Thomas’s Trinitarian theology is in no way meant to crack open the mystery of the Godhead, three in one. His theology of the Trinity in the first part of the Summa undertakes a simple and unambitious, if very important, task, that, namely, of clearing the space of mere problems that would obstruct our access to the deep mystery of God’s inner life as revealed to us in Christ. That technical metatheology does not do the substantive theology of the Trinity. It creates the space for it, space that, as Thomas shows in the Summa’s third part, is best filled by prayer. That discussion of the Trinity in Part I of the Summa is a kind of textbook of theological grammar: prayer, on the other hand, is a grammatically correct sentence uttered in conversation within the faith and love of the Trinity.

And that is why it is so obviously true that no one could preach a sermon sourced out of Thomas’s Trinitarian theology in the Summa’s first part, and why it is true that as it stands it tells us nothing about prayer. But the impression that the Summa nowhere provides either source material for preaching on the Trinity or any theology of prayer is mistaken. As to the preaching, if any theologian knows about that subject, Thomas does. He is a Dominican after all, and, as Herbert McCabe used to say about his ministry, Dominicans don’t pray, they preach—which doesn’t mean, obviously, that Dominicans don’t pray. Of course they do, any Christian does. But not all Christians go in for preaching as a way of holiness, which is what Dominicans especially do. And as to prayer as a common practice of all those who preach, it is often forgotten and rarely remarked that uniquely among medieval compilers of theological summaries Thomas offers not just that formal treatise on the Trinity in the first part of the Summa, or only a formal treatise on the Incarnation in its third part: for capping those schematic and formal outlines of the mysteries of God in God’s own self and in Christ, Thomas offers in the third part of the Summa an unprecedented discussion of the central episodes, or “mysteries” as he calls them, of the historical life of Jesus. These are consciously designed preaching materials for novices in the Order of Preachers. Step by step, Thomas recounts in over 500 columns of narrative theology the story of Jesus’s life—his conception in the womb of Mary, his birth, his baptism, his temptations, his exchanges with fellow human beings, his preaching, his miracles, his temptations, his passion, his death, his burial, his descent into hell, his resurrection, his ascension, and his exaltation on the right hand of his Father. This is a fusion, found in no other theologian before him and in few since, of the theologically systematic and the narratively homiletic; it is a Life of Christ in which Thomas says he will give an “account of the things that the Son of God did or suffered in his human nature.” And so he does. Central to Thomas’s story of the human life of Christ are two discussions of how the historical Jesus prayed. It is there, in those discussions of the man Jesus’s prayer, that Thomas brings his teaching on the Trinity into the center of the Christian life.

Prayer

When Thomas writes about prayer in general, as he does in the second part of the Summa, he means something more specific than we commonly refer to by our very generic English word for it, which today includes all sorts of different speech acts: thanking God, praising God, meditating about God, contemplating God, asking God, expressing before God our contrition, sadness, joy, anger even. In fact the panoply of human conversational styles falls under the word prayer as we today construe it, just so long as they are all forms of address to God.

By contrast with our modern usage, and in an older tradition derived from the church fathers, when Thomas thinks of prayer he has in mind that much narrower practice, as we call it, of “petitionary” prayer, that is, the practice of asking God for what we want. And this is not just his primary word for it. He takes for granted that asking God for things is, and should be, our principal practice of conversation with God. It is not, as he reminds us, that God doesn’t know our needs anyway so that we have to inform him of them, for our Father in heaven knows all our needs well ahead of us. It is rather we who need in prayer to set our wants and desires before God honestly and truthfully just as we experience them, no matter what they are, so that by means of that prayer our Father in heaven can read our needs back to us, interpret them for us. For, Thomas says: “Oratio est quodammodo interpretativa voluntatis humanae,” that is, “Prayer is in a certain manner an interpretation of what we human beings want.” That is the reason why, though God does not need our prayers, we certainly do: for we do not always know what we want, our desires are complicated, “plicata,” he says, crumpled up, folded over onto one another, so that we do not recognize what they truly are and for that reason cannot own them. Therefore, we have to unfold them, “explicate” them, in the only way possible to us, just as we are, that is, confused and befuddled even as to what desire we are there expressing. That is the way of honest prayer. Because we do not know what we really want, we can only place our desires before God exactly as we experience them so that God can read them back to us, ut eas impleat, Thomas says, that is, so that our Father in heaven may read back to us our truest desires and fulfill them. Thus, in prayer, our desires are at once honestly expressed just as they are and without pious pretense, and at the same time those desires are interpreted, explicata, as to what they really mean. For not by any means are what we think we want and what we truly want always the same. We all know that, being prone to passive self-ignorance at the best, and at the worst to active self-deception.

In this way Thomas shares none of that squeamishness about petitionary prayer that one hears sometimes indulged by very high-minded people, as if there were something mean, spiritually immature, small-minded, and excessively needy about asking God to meet our petty desires and wants, and as if spiritually grown-up people will pray only that God’s will be done come what may. Strange it is how such mature Christians neglect the rather grubbier practice, also recommended by Jesus, of asking our Father in heaven for daily supplies of bread. Sophisticated prayer, Jesus tells us, is for Pharisees, who like to be heard standing up before an audience and in loud voices informing God of their disinterested desires and evidently expecting encouraging pats on the back for their adult high-mindedness. The publican, by contrast, being a sinner, hides away and simply groans. He is needy and though no doubt ashamed of his needs prays desperately out of them. He knows being in need is all he has got to offer.

The Prayer of Jesus

But groaning, Thomas says, is not just for sinners. Did Jesus pray, he asks, secundum suam sensualitatem? The Latin phrase is hard to translate, but the question means something like “Did Jesus pray out of (or perhaps “in accordance with”) his animal desires?” and, in character, Thomas answers that it depends what you mean. Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane “began to be greatly distressed and troubled,” Mark tells us. He “fell to the ground”—this reads like the narrative of an eyewitness, and the tradition is that Mark as a very young man or boy was there at the time and witnessed Jesus’s distress. And then Jesus prayed, and by all accounts very bluntly too, for the grammatical mood is not deprecating and conditional, it is an unconditional imperative, the plea of a troubled man, a man in pain: “Father, for you all things are possible: remove this cup from me,” as if to say, “Father, you are free to will it. Do so will.”

Of course, you will say, there is more to it than that cry of desperation, for Mark’s account adds that Jesus said: “Yet not what I will, rather what you will.” But the addendum is otiose. Mark’s Jesus is no stoic. You do not need the additional phrase, because it simply glosses the pleading as having been placed before his Father, God, that is, it glosses it as a prayer, and that rather goes without saying, since the address to his Father is already there in the pleading. In short, Jesus’s words place his animal need before God, and that is what makes his fear to be his prayer. That is the reason, Thomas says, why Jesus is shown as praying secundum suam sensualitatem, he makes a prayer out of his animal self. It is “for our instruction . . . [that Jesus] wanted us to know what in his natural human will he desired, and to what his animal impulses drew him.” But it is important not to get this wrong. To say that Jesus “prays for our instruction” is not to say that he does not really pray in distress but only pretends to. His distress is real, and, Thomas says, it “shows us that it is permitted for human beings out of their natural desires to will something other than what God wills.” And then he adds the authority of Augustine in support of what he knows to be for some, perhaps especially for those spiritual sophisticates, a surprisingly raw, unprocessed, and unspiritual thought. For Augustine says it was

In this way that Christ, bearing the weight of his humanity, shows that he has a human will of his own; and in accordance with that human will he prays “Take this chalice away from me.” But because he wished to be a righteous man and to be moved back toward God, he adds, “Not, though, as I wish it, but rather as you do,” which is as if to say [to us]: “See yourself in me: and you will see that it is quite acceptable to pray for what you wish even though God may wish otherwise.”

Jesus, at least, prayed honestly as any human would. Indeed, you could say that his honesty before God was his prayer. At any rate, so say Thomas and Augustine.

Such honesty can make us uneasy. Fake piety is easier than such unprocessed neediness. And there is something humanly truthful about the prayer of Jesus in Gethsemane as Mark recalls it. But that realism itself pales before Mark’s account of the even starker fear expressed in Jesus’s last words on the cross. There is a disconcerting pathos about Mark’s dying Jesus, for if he trusts his Father he does so without reassurance, and not only because of his physical pain, though there is in him none of the magisterial calm that Luke and John report; nor is it only because he has been abandoned by men, above all by his friends. It is because he fears the ultimate disaster and seems to experience it—that he has been abandoned even by his Father. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” he cries. And he dies, his question falling upon deaf ears as it would seem, for in Mark’s Gospel it is left unanswered. Luke tells us that in Gethsemane an angel was sent to Jesus to console him. No such encouragement is offered here in Mark’s narrative as death beckons, no inspiring last words heroically evoked, just a “loud cry” and then a dead and empty silence. As I understand it, the original version of Mark’s Gospel ended with another emptiness, that of the tomb, the Resurrection narrative being later tacked on by another hand, as if the bleakness of this downbeat ending was, as it stood, too much to bear.

At all events, even as Mark’s narrative now reads, if Jesus’s prayer in the Garden teaches tough lessons, Jesus’s prayer on the cross might seem to be little short of blasphemous. But for all that it might seem to be the despairing cry of a wretched man who has lost faith in his Father’s will, it isn’t. However bleak and needy, it’s still a prayer to his God, indeed it is a further, yet more radical, model of how to pray, offered, once more Thomas says, “for our instruction.” Certainly it is stronger meat, as ways of praying go, than the resigned calm of Luke’s “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” And just as surely Mark’s narrative requires us to adjust our notions of what good praying looks like, only this time the adjustment needed is more disturbing still. Surprisingly it was the centurion standing by who somehow understood what had just happened: “Truly this man was the Son of God,” he said, it seems on the evidence alone of those desperate last words of a humiliated Christ. That is pretty smart theology for a conscripted corporal in the Roman army.

Prayer and the Trinity

So where is Thomas with all this? And what has it to do with those formal, and professorial, questions of second-order theological epistemology that I raised just now, with the rational proofs of the existence of God, with the dauntingly technical speculative theology of the Trinity, with that severely negative theology, with that trope of the “darkness of God”? The connection lies in the nature of that prayer of Christ in which is shown why, when Christians, at any rate Catholics, Roman or otherwise, invoke the Trinity in their lives, they pray “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” and as they do so make the sign of the cross. When they do this it is as if to say: it is true, as even the philosophers know, that, God not being any kind of thing, we are drawn even by reason into God’s impenetrable cloud of unknowing; it is true that that the same darkness of God is deepened by the very demonstration of God’s existence, which, far from placing God within the grasping hands of reason, shows that in their highest powers of reason human beings are drawn even more deeply and surely into the divine darkness; and it is true that by the revelation of the mystery of the godhead they are drawn into the Trinitarian being itself, and so into some share in how God knows and loves himself; yet there too they are drawn into a mystery that is, in itself, utterly beyond human powers to understand. As we grapple with those overlapping and ever deepening mysteries of reason and of faith, the best that can be done with it all is to ask the theologians to spell out and articulate, as does Thomas in his Summa, some formal, speculative propositions with which they can, as it were within a framework, stabilize our many sorts of discourse about God. But when Christians want to read the Trinity within their lives, or better, when they want their lives to be read within and by the Trinitarian life, there they truly enter by way of all knowledge and desire into the darkness of God mapped onto our human ground, within their sight. Then it is that they make the sign of the cross. Then it is that they enter into the true darkness of God, God’s own darkness in the person of the crucified Son.

For the cross is what the Trinity looks like when it becomes visible within human history, and it appears only that way because of our sin. Jesus’s desolation in his passion and death wreaks havoc with our natural expectations of how a God should appear among us, for on the cross is no superhuman, but one “despised,” and as one seeming to be, in the words of Isaiah, “the most rejected of men.” Here is no theoretical unknowing, for here on the cross the godhead is not recognizable even as a man, never mind as a God. But that is how things stand for the theologians, they have to work with what is there in the darkness of God thus revealed, or not at all. For Jesus’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane and on Golgotha is where the Trinity is inscribed within time, history, and human experience, inscribed upon our sensual, animal being. Jesus’s last words are the broken prayers of a man who can address his Father only secundum . . . sensualitatem. Here, then, finally is discovered the concrete and lived meaning of the darkness of God, now no longer as a metatheology, but as an event that falls within the narrative grasp of first-order experience; the darkness of God is now the Trinity come among us and palpable as an animal’s pain. Herein lies the mystical, the mysterium fidei that is within the human grasp to be lived. And I suppose we should be taken aback that if, as Thomas said, the mystery of the inner life of the Godhead has only one way of appearing among us, namely “in its effects” in history and time, then on such an account that Trinitarian life is known to us in and by way of the death throes of a man falsely judged criminal by some very religious people not unlike ourselves. But that is what the world is thereby revealed to be, and that is why we have been taught to make the sign of the cross when we call upon the Trinity in prayer. The Trinity and the cross map on to one another like a palimpsest of transparencies superimposed the one upon the other: either way you have to read through the one to read the other. “Surely this man was the Son of God,” says the Roman mercenary, getting it: surely the mystery of the Godhead is made present to us, at last, on the cross.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This excerpt of Chapter 2, “One with God as to the Unknown': Prayer and the Darkness of God," from Denys Turner's recently published book, God, Mystery, and Mystification is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our exceprts from this collaboration here.