If only Russia had been founded

by Anna Akhmatova, if only

Mandelstam had made the laws . . .

—Adam Zagajewski, “If Only Russia,” 1985

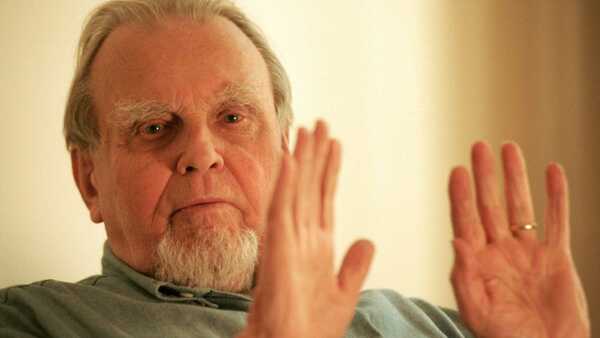

Adam Zagajewski was like a butterfly catcher. I see him sitting alone for days in his room, sometimes staring at his walls, just to grasp split seconds of truth; to glimpse infinity. This is because he was a student of mysticism, a pupil of wonder. He practiced humorous and tender irony. He was also a double exile, and much of his writing, consequently, revolved around this topic.

In light of the current invasion of Ukraine, Zagajewski’s poem “To Go to Lvov” comes to mind first. Lvov because that is where Zagajewski was born and from where he was first exiled (his family was forced to resettle from Polish Lvov, which became Soviet after the Yalta Conference). This ecstatic poem redefines and recuperates the concept of exile. In this case, exile as an imperative to continual recreation of the lost place in the act of writing.

To go to Lvov. Which station

for Lvov, if not in a dream, at dawn, when dew

gleams on a suitcase, when express

trains and bullet trains are being born. To leave

in haste for Lvov, night or day, in September

or in March. But only if Lvov exists,

if it is to be found within the frontiers and not just

in my new passport, if lances of trees

—of poplar and ash—still breathe aloud

like Indians, and if streams mumble

their dark Esperanto, and grass snakes like soft signs

in the Russian language disappear

into thickets. To pack and set off, to leave

without a trace, at noon, to vanish

like fainting maidens . . .

“To go To Lvov” depicts the ecstasy that exile, in its longing, brings. Here the exile and desire for a lost place are intertwined. Lvov is everywhere because it resides in memory and imagination. Lvov recreated anew in memory “brimmed the container, / it burst glasses, overflowed / each pond, lake, smoked through every / chimney.” Deprivation and renunciation become the blessings because the resurrected in memory Lvov is paradisaical. The home is found in exile, in writing about Lvov. The poem relies on the repetition “there is so much Lvov” which makes this city with “green armies of burdocks”; and “the cornets of nuns” sailing “like schooners near the theater” eternal. Even though there is too much Lvov, the desire for it is never satiated; just like in a good theatre performance, it must “do encores over and over.” Lvov lost becomes hundredfold to the point of “unrealness.”

It was too magic, too heavenly in the first place to be true on this earth. That is where “the unhealable rift” of exile arises in the poem. “Banishment” and destruction are evoked through the image of scissors, razor blades, and penknives. Perhaps this memory is too traumatic; therefore, it is staged through props. The end of the poem could be considered a definition of exile, which is not just a geographical phenomenon, but a mental and spiritual one.

. . . and trees fell soundlessly, as in a jungle,

and the cathedral trembled, people bade goodbye

without handkerchiefs, no tears, such a dry

mouth, I won’t see you anymore, so much death

awaits you, why must every city

become Jerusalem and every man a Jew,

and now in a hurry just

pack, always, each day,

and go breathless, go to Lvov, after all

it exists, quiet and pure as

a peach. It is everywhere.

The end of the poem shifts the meaning of exile from a geographical and physical phenomenon to an existential human condition, “Every man is a Jew.” Lvov, lost geographically, becomes ubiquitous; it is everywhere now.

Zagajewski was an exile in both senses: the historical one and its Greek etymological sense as well. The former one is, in Edward Said’s definition, “the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home.” The latter one, as Ruth Padel reminds us in her book, The Mara Crossing, goes back to the origin of the Greek word xeniteia, a spiritual detachment practiced by the monks of antiquity—as the choice of the desert in order to restore the soul or converse with Mystery. This meaning is congruent with the Christian understanding of human existence, to bring to mind a fragment from Genesis 12:1 in the more poetic King James translation: “Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee.”

In connection to the origin of Greek word xeniteia, in his autobiography, Minima Moralia, written in exile, Theodore Adorno also says: “it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.” Adorno warned against complicity with the culture of commodity. To refuse this mainstream mentality—life as a commodity—is exile’s intellectual mission. Each intellectual, or artist, should in fact choose exile, Adorno proposed. Adorno claimed that our only home was in writing. Exhibiting a parallel sensibility, Zagajewski writes in his essay, “Against Poetry”:

Contemporary mass culture, entertaining and at times harmless as it may be, is marked by its complete ignorance of the inner life. Not only can it not create this life; it drains it, corrodes it, undermines it.” Poets’ role has been to defend and nourish the inner life; to sit in silence and communicate with the inner voice, which Zagajewski perceived as “the foundation of our freedom (138).

His poem “Soul,” written during his exile in Paris, points to this double exile (internal exile, perceived as a vocation or mission, within external exile). The first line of the poem declares: “We know we’re not allowed to use your name.” During the communist Regime in Poland, the soul was the opium of the poor. To choose the soul was a choice of exile. Believers who were faithful to Church, were often ostracized or even murdered. Not only is the soul inexpressible, but also forbidden. It is ironic that the poem was written during Zagajewski’s exile in Paris, because theoretically, away from the regime, this is the place where one could freely talk about the soul. Yet, the soul is “exiled” or suppressed in our culture regardless of what ideology we live in.

We know that you are not allowed to live now

In music or in trees at sunset.

We know—or at least we have been told—

that you do not exist at all, anywhere.

And yet we still keep hearing your weary voice

—in an echo, a complaint, in the letters we receive

from Antigone in the Greek desert.

Here again, we see the shift from historically and politically determined exile to an internal or spiritual sense of xeniteia. This is also true of Zagajewski’s life. Once external exile was alleviated by the collapse of the regime and, later, Zagajewski’s return to Krakow, the poet was “exiled” again by many contemporary poets in Poland. And while he worked in the U.S., he never truly felt he belonged to America either. He was in the state of in-between.

Many young poets ostracized him for being too lofty, too dignified in style. In fact, Zagajewski, in one of our meetings when I shared my Polish book of poems with him, said: “Your poems prove to me that poetry is an x-ray of the soul, after all.” This was not a very popular definition of poetry in the Polish contemporary poetic landscape, which is very much influenced by American poetry, particularly the New York School of poetry and postmodernism.

In poetry, according to Zagajewski, we look for contact with the sublime. Zagajewski understands the sublime, as Longinus did, as “a spark that leaps from the soul of a writer to the soul of his reader” (31). He reflected a great deal on the nature of poetry. He was an erudite scholar with a philosophical inclination. In his essay, A Defense of Ardor, Zagajewski poses the question: “But what is poetry?”—a rhetorical question, as nobody has a definitive answer, he claims. However, he claims to see:

Poetry in its movement “between”—both as one of the most important vehicles bearing us upward and a way of understanding that ardor precedes irony. Ardor: the earth’s fervent song, which we answer with our own, imperfect song. We need poetry just as we need beauty . . . Beauty isn’t only for aesthetes; beauty is for anyone who seeks a serious road. It is a summons, a promise, if not of happiness, as Stendhal hopes, then of a great and endless journey.

As Zagajewski claims, we do not go to poetry for sarcasm or irony, but for fire and flame that accompanies spiritual revelation: for vision. This view of poetry put Zagajewski at odds with contemporary Polish poets who were fascinated by Frank O’Hara and tired of the Polish masters such as Czesław Miłosz. It did not put him at odds with old and young American poets, however, who were hungry for poetry as necessity, and tired of the poetry of linguistic playgrounds and commodities. American poetry was already weary of the entertainment wastelands, of countless simulacra of Mickey Mouse. Instead, they welcomed the ardor in poetry. Hence the popularity of Zagajewski’s poems here in the United States.

To better understand, however, Zagajewski’s poetic ontologies and how they evolved, one must delve into his Polish poetic heritage, which is so deeply rooted in Romanticism. For a long time, Polish Poetry has maintained a Romantic heritage. A poet had a special calling. It was a calling to save the nations. Czesław Miłosz says: “What is poetry that does not save / Nations or people?” Polish poetry has been inseparably linked to the Polish nation, issues of patriotism and civic discourse. One of the reasons was that since 1795, when Poland (under the name “the Commonwealth”) ceased to exist, Polish culture started substituting for Polish institutions. Polish poetry was yoked into national politics. Finally, in 1918, poets attempted to cast off the cloak of militant poetry; that is to say, poetry speaking on behalf of the nation. One of them was the poet Jan Lechoń, who belonged to the Skamander group. His line: “And in the spring let me see spring, not Poland” became a manifesto.

Yet, during the period of Stalinism and Communism, this Romantic understanding of the poet as a missionary and national bard reasserted itself again. Poetry again became a witness to truth and beauty. In “The Envoy of Mr. Cogito,” poet Zbigniew Herbert writes:

repeat old incantations of humanity fables and legends

because this is how you will attain the good you will not attain

repeat great words repeat them stubbornly

like those crossing the desert who perished in the sandand they will reward you with what they have at hand

with the whip of laughter with murder on a garbage heapgo because only in this way you will be admitted to the company of cold skulls

to the company of your ancestors: Gilgamesh Hector Roland

the defenders of the kingdom without limit and the city of ashesBe faithful Go

In yet another poem, “A letter to Ryszard Krynicki,” Herbert writes: “The task of a poet is to build tablets of values.” My generation of poets born in the 70s knew by heart the Czesɫaw Miɫosz’s poem: “You Who Wronged”:

You who wronged a simple man

Bursting into laughter at the crime,And kept a pack of fools around you

To mix good and evil, to blur the line,

Though everyone bowed down before you,Saying virtue and wisdom lit your way,

Striking gold medals in your honor,

Glad to have survived another day,Do not feel safe. The poet remembers.

You can kill one, but another is born.

The words are written down, the deed, the date.And you'd have done better with a winter dawn,

A rope, and a branch bowed beneath your weight.

Composed in 1950, “You Who Wronged” was a manifesto of moral witness. The poetry of moral witness was partially continued by the New Wave Generation to which Zagajewski belonged. These were particularly poets who made their debut after 1968: Stanisław Barańczak, Ryszard Krynicki, Julian Kornhauser, and Ewa Lipska, just to mention the most representative. The poets of the New Wave believed that a poet was responsible for the world. Ryszard Krynicki, for example, in one of his poems wrote: “One should write in a way so that a hungry person will think it’s bread.” Such poets as Stanisław Barańczak contested the “newspeak” widespread by mainstream media under the Communist Party. Barańczak claimed poetry should be composed of distrust. Poetry should debunk lies and ideologies. For Zagajewski, poetry constituted the conscience of society. The New Wave generation insisted on the necessity of addressing politics in their writing. In their early manifesto book, entitled The Unrepresented World [świat Nie Przedstawiony], published in 1974, Zagajewski and Kornhauser propagated the style of speaking straight [mówienie wprost] in their own attempt to oppose the newspeak. Poetry had to “unfalsify” reality. It had to call things by their names.

In his poem “Truth” from the collection Komunikat [Announcement], Zagajewski writes: “Say the truth, that’s why you serve.” In another poem, “Don't Allow the Lucid Moment to Dissolve,” he writes: “Don't allow the lucid moment to dissolve on a hard dry substance/you have to engrave the truth.” Hence, in the poetry of the New Wave there was no place for relativism. Instead, Zagajewski proposed a new realism that links ethics and aesthetics. Let us take a look at Zagajewski’s poem: “Try to praise the mutilated world”:

Try to praise the mutilated world.

Remember June's long days,

and wild strawberries, drops of wine, the dew.

The nettles that methodically overgrow

the abandoned homesteads of exiles.

You must praise the mutilated world.

You watched the stylish yachts and ships;

one of them had a long trip ahead of it,

while salty oblivion awaited others.

You've seen the refugees heading nowhere,

you've heard the executioners sing joyfully.

Zagajewski recited this poem at the 2014 Colby-Sawyer College reading to which I invited him. I remember him explaining to my students the origin of this poem, which had brought him instant fame in the U.S. after it was published in The New Yorker soon after the September 11 tragedy.

The poem was written, however, much earlier—in the 1960s during a hike with his father in Poland’s Beskidy Mountains. While hiking, they saw the abandoned villages that once were inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians who had been forced to leave and resettle by the Communist government. Despite catastrophic events, Zagajewski pays attention in his poem to small epiphanies, micro-wonders outside of history. Despite the fact that this poem had been inspired by witnessing the exiled Ukrainian community in Poland, Zagajewski mentions refugees only once and rather briefly. The rest of the poem focuses on individual moments of ephemeral happiness, moments when an inner voice speaks.

. . . You gathered acorns in the park in autumn

and leaves eddied over the earth's scars.

Praise the mutilated world

and the grey feather a thrush lost,

and the gentle light that strays and vanishes

and returns.

We see in this poem already Zagajewski’s more individual path, which marked him as distinct from other poets of the New Wave generation. This poem indicates Zagajewski’s shift from collective responsibility to “a singular feather the thrush lost.” It is in solitude that each “I” can choose hope over despair, beauty over the horrors of history. As Clare Cavanagh observes in Lyric Poetry and Modern Politics: Russia, Poland, and the West, by the mid-eighties, Zagajewski chose to “dissent from dissent” in contrast with other “sixty-eighters.”

Zagajewski has exchanged “collective subject” for “lyric speaker” who pledges his allegiance to “unusual, singular, exceptional things, such as a giraffe’s neck” (228). As Cavanagh aptly notices, Zagajewski’s need was “to cultivate not just solidarity, but solitude, his singular self and viewpoint—not least in hopes of pointing others to their own unrepeatable individuality” (228).

The switch from collective being in poetry to solitude did not mean, however, shedding off the responsibility of the poet. It was, rather, shifting it to the interior life, the cultivation of memory and even—with humble deflections of cliché—mysticism.

I have come to think the poem “Mysticism for Beginners” exemplifies the task of the poet. In this epiphanic poem every micro-wonder we encounter in life is only a prelude to something much greater in the afterlife.

Suddenly I understood that the swallows

patrolling the streets of Montepulciano

with their shrill whistles,

and the hushed talk of timid travelers

from Eastern, so-called Central Europe,

and the white herons standing—yesterday? the day before?—

like nuns in fields of rice,

and the dusk, slow and systematic,

erasing the outlines of medieval houses,

and olive trees on little hills,

abandoned to the wind and heat…and the little nightingale practicing

its speech beside the highway,

and any journey, any kind of trip,

are only mysticism for beginners,

the elementary course, prelude

to a test that’s been

postponed.

In “Mysticism for Beginners,” Zagajewski portrays each of us as a pupil of elementary mysticism; as a pilgrim whose life will culminate in a final exam. In order to get there, we need to choose exile, xeniteia—a voluntary departure from our physical place of comfort in order to reunite with our spiritual place.

Between 2003–2008 I attended summer poetry workshops and lectures organized by Adam Zagajewski and Edward Hirsch. Zagajewski was then an associate professor of English in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston. Thanks to these workshops, I had a chance to converse, eat, chat, and walk around Krakow with such poets as Jorie Graham, Carolyn Forche, Ann Carson, Tony Hoagland, Robert Pinsky, Phillipe Levine, and others. I was a feisty person when it came to discussing poetry. I would raise my hand irreverently and beg to differ with masters.

Zagajewski, however, would approach me every year and express his gratitude for my engagement, even though sometimes I expressed uncompromising opinions about poetry. I understood only later that he appreciated passion in poetry, the major theme of his famous book of essays entitled, A Defense of Ardor. When the seminars ceased, Zagajewski and I started to meet once each summer for tea or coffee; we would meet at Pumpkin Café on Krupnicza Street in Kraków and discuss poetry. Now that he is gone, I look at these meetings as my private and elementary lessons in mysticism.