The religions known as revealed offer a strange characteristic: contrary to what is often repeated (when denouncing the supposed “fanaticism” of believers), they do not presume that their members already and from the outset accept the concerns of their (supposed) Revelation. The proper and authentic character of Revelation implies on the contrary that what is at issue (the revealed) exceeds all efforts to receive it, or even the magnitude of any desire to adhere to it. To be sure, a Revelation always aims in the last instance to fill the gap between what is revealed and those to whom it is revealed in a final vision; but its first intention and effect is to register and even to deepen this gap.

Precisely because it manifests what exceeds common knowledge, Revelation implies that no one can ever perceive it adequately or receive it according to its measure. And in any case, if it could be received adequately and without remainder, it would no longer have to do with a revelation (and a fortiori a Revelation), but the mere pedagogical transmission of a knowledge accessible as such, about which it would only offer a provisional teaching. A Revelation is worthy of this title only as long as it remains incommensurable with those who accept it—for if they accepted it according to their measure and even wholeheartedly, they would not be able to receive it according to its measure; if they accept it as such, they therefore can, on principle, at least at first, only miss it, and also refuse it, or indeed even deny it, well before the cock crows three times.

From this there follows the first concept: the witness. In the daily routine of what happens as a banal event and not as an object, a witness is defined by the gap within himself between, on the one hand, what he saw, heard, or in short experienced of the incident that he can, with all the veracity of sincerity, transmit to others as verifiable information; and, on the other hand, what he can himself understand or explain about the incident, which often remains for him limited, if not unclear, because he is not in the theoretical position required to reconstitute the context, the plot, and therefore the signification of what unfolded. The witness encounters the event that is revealing itself without, however, wholly understanding it; indeed, he has encountered it all the more indisputably when he does not understand it completely; the honest witness should always begin by saying, “I heard, but I did not understand” (Daniel 12:8, LXX). And this is why it sometimes happens that the witness leads another to suspect or understand more, sometimes even much more, than he himself understands.

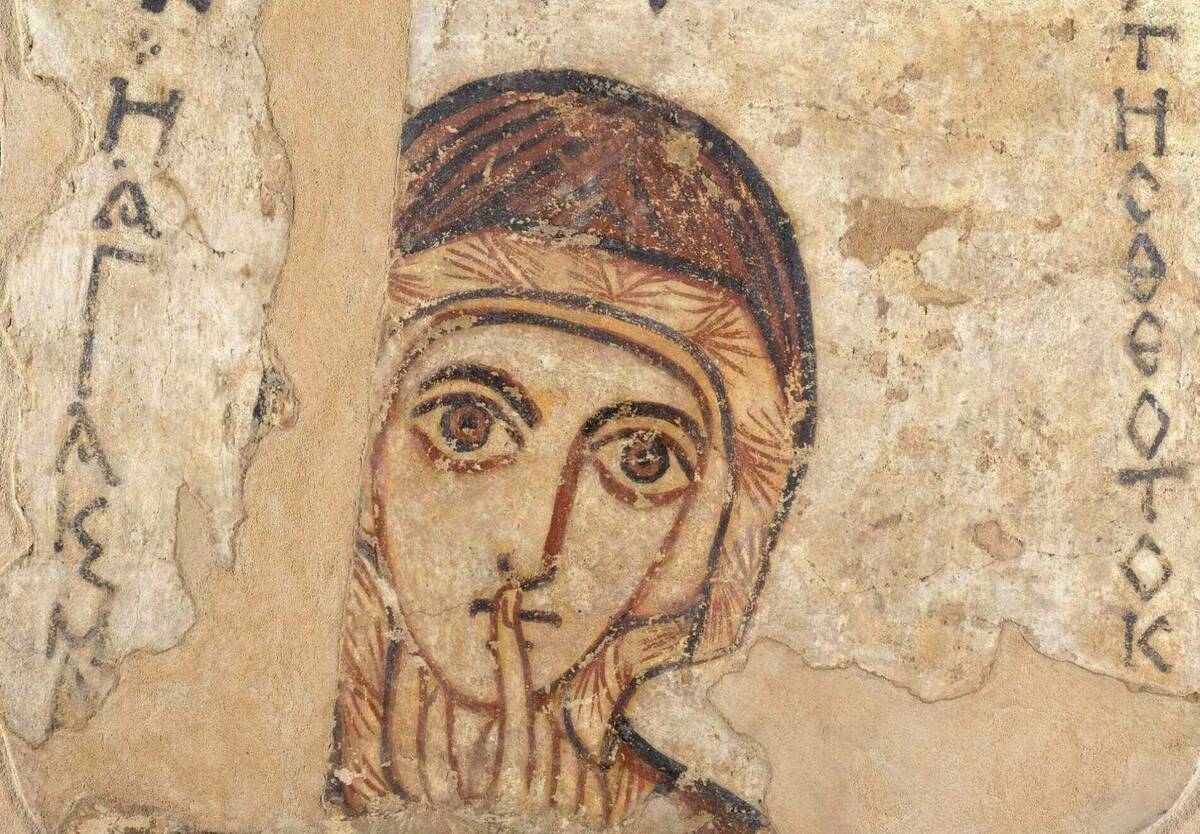

More precisely, he reports to another the very things that escaped him in what he nevertheless really and truly experienced, leaving this other to attempt to understand it more than he himself succeeds in doing. In the case of a Revelation, then, the witness discovers himself all the more lost in this gap when it is ultimately a question of the irruption of God or of the divine, or in short of what “no one has ever seen (οὐδεὶς ἑώρακεν πώποτε)” (John 1:18, taking up Exodus 33:20–23). What is more, deep down, no one is more aware than the witness that he does not understand what he has nevertheless seen (maybe without seeing, in the usual sense of a vision that possesses what it perceived); he is all the more aware of it if he thinks that it is a matter of nothing less than “the icon of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15) and “the brightness of his glory” (Hebrews 1:3). What qualifies the witness, then, as authentic and credible lies strangely in his knowing better than anyone else that he really has seen and heard what he cannot and often must not truly understand.

An episode from the Gospel of John perfectly illustrates this hermeneutic situation. When a man born blind recovers his sight after Christ smeared his eyes with mud and saliva, and then sent him to wash in the pool of Siloam, and he is first asked if he is indeed the man born blind, who was healed, he naturally doesn’t doubt it for an instant: “I am he” (John 9:9); and again, when someone asks him who healed him, he confirms that it was “the man called Jesus” who healed him (John 9:11, and see 9:15), for he can witness to this fact. But to the question whether he knows “where he [Jesus] is” (in fact, “where he comes from,” 9:29), he, as witness, cannot know. He thus answers very precisely: “I don’t know (οὐκ οἶδα)” (9:12), though he knows very well that he has been healed: “One thing I do know (ἓν οἶδα) is that I was blind and now I see” (9:25); he does not know, nor does he claim to know, how or by whom he was so indisputably healed.

Here again, the witness knows what he knows, without being able to explain adequately that which nevertheless he has no doubts about and can stand by even at the cost of possible retaliation. Now, it is precisely by exposing himself for what he does not understand that he testifies in an epistemologically correct manner to the invisible as such, and thus to the inconceivable as such by which he finds himself confronted, without having sought it out. In a sense, then, the witness always witnesses in spite of his incomprehension; or rather, by testifying despite himself, he testifies correctly through his very incomprehension.

Of course, in a second moment, the man born blind, who now sees, will cross over the threshold where his parents have stopped short: “to recognize (ὁμολογεῖν) him [Jesus] [as] the Christ” (9:22). But not yet in front of the Pharisees: “If he is a sinner, I do not know (οὐκ οἶδα). One thing I know (ἓν οἶδα) is that I was blind and now I see” (9:25): here, he continues to hold the strict posture of the witness, riveted to the facts, without claiming to understand them. It is the Pharisees who, without wanting to, push him by their accusation to become not only a witness, but a believer: “You are that man’s disciple” (9:28); but in doing this they indicate the division or gap between the witness and the disciple, because they themselves claim to have crossed it; they affirm indeed that they understand clearly the signification of the sign, namely that of Christ: “You are that man’s disciple; we are disciples of Moses! We know (οἴδαμεν) that God spoke to Moses, but we do not know where this one is from (οὐκ οἴδαμεν πόθεν ἐστίν)” (9:29). Their claim is false, for in fact they “do not know” what they imagine that they understand clearly, as the man born blind, still a witness, points out to them, knowing that they do not know: “This is what is so astonishing (θαυμαστόν), that you do not know (οἴδατε) where he is from, yet he opened my eyes. We know (οἴδαμεν) that God does not listen to sinners” (9:30–31). His last reply perfectly defines the posture of the witness: it is a fact that “It is unheard of that anyone ever opened the eyes of a person born blind!”; but the interpretation of the believer is already showing, which allows him to understand correctly the signification of the sign: “If this man were not from God, he would not be able to do anything” (9:32–33).

It is only once he is “thrown out” (9:34) by the Pharisees, and thus liberated from the false understanding of the fact, that the witness can rise, as believer, to the correct signification. Or rather, he receives it from elsewhere, from Jesus who calls him and, for once, identifies himself: “‘You have seen him and the one speaking with you is he.’ He said, ‘I do believe, Lord’” (9:37–38). In order to see truly, the witness must not only testify that he saw, but believe in the one who made him see. To see is not enough to understand; one must love in order to know: “I have called you friends [whom I love and who love me, φίλοι], because everything I have heard from my Father I have made known to you (ἐγνώρισα ὑμῖν)” (John 15:15). Now the vision returns: to see, it is not enough to see as a reliable witness (the man born blind) or a challenger (the Pharisees), for the witness does not understand everything he sees; to see, one must believe: “I came into this world for judgment, so that those who do not see might see, and those who do see might become blind” (John 9:39). The witness does not claim on his own to understand what he sees; rather, he awaits precisely that which gives itself to be seen.

A first characteristic of every Revelation thus stands out: it shows itself not through a comprehensive knowledge, but through the recognition of an incomprehensibility; neither at first nor ever, perhaps, does it let itself be led back to a full intelligibility according to our rationality and following a finite hermeneutics; it is exposed thanks to the nevertheless certain non-knowing of the witness who accepts to understand from elsewhere.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article is excerpted with permission from Revelation Comes From Elsewhere: A Contribution to a Critical History and a Phenomenal Concept of Revelation, translated by Stephen E. Lewis and Stephanie Rumpza (Stanford University Press, 2024). All rights reserved.