For the first time in the history of theorizing about literature and art, certain traditional notions have lost their prestige. Mimesis is one. Our modern idea of esthetic creation as mimesis, as a process of imitation, goes back to Aristotle who really borrowed it from Plato, although in Plato esthetic mimesis has negative connotations which we do not really understand.

Until recently mimesis has remained the imperial concept, the number one signifier of Western literary theory. But its signification, the meaning we attach to the term, has undergone strange metamorphoses. In Aristotle, mimesis is essentially dramatic and theatrical; the actor is a mime who imitates an action. During the Renaissance and after, Western writers felt inferior to their Greek and Roman predecessors and they exhorted each other to imitate them. A little later they became less modest and they decided they needed no intermediaries to imitate nature, meaning human nature. The concept of nature was gradually broadened and, in the nineteenth century, it turned into “the whole of reality”—whatever that means. A vast middle-class audience demanded an art that would mirror its own perception of the world, its preoccupation with material objects, inseparable from the esthetics of realism and naturalism. Writers should aim at “a faithful representation of reality.”

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the poet Charles Baudelaire and others reacted violently against the idea that the function of art was to imitate reality. They equated this idea with a defense of middle-class provincialism and philistinism. In our time, the rebellion of modernism has become the new orthodoxy. In recent years, the general emphasis on language and literary structuralism has discredited mimetic realism, at least on the European continent. Language is made up of arbitrary signs. There is no common yardstick between words and things, and the idea that literature can imitate reality is entirely mythical. It depends on an act of faith in the universal validity of a certain discourse.

It is true that the esthetics of mimetic realism are often associated with other Western ideas such as faith in science, in social equality, in political democracy, and more generally with faith in historical progress. Realistic literature is a dimension of that most powerful grasp on reality which is the essence of the West and, as the West realized this essence, its literature became more mimetic and realistic. When it fails to do so it neglects its mission; its true nature is perverted. One finds such ideas not merely in the Marxist theoreticians of literature such as Georg Lukács, but in non-Marxist critics as well. In the magnum opus of Eric Auerbach, entitled Mimesis, not only is the literature of the Christian and post-Christian West regarded as more mimetic and realistic than any other, but as becoming more so during the course of history. The unity of the works and the unity’s dynamics are one with this single idée-force.

One interesting aspect of Auerbach is his insistence on the role of the Gospels in this orientation toward mimesis. The word “mimesis” is Greek but the impetus is Judaic and Christian. In order to demonstrate his point, Auerbach refers at some length to the episode of Peter’s denial in the gospel of St. Mark. Auerbach vigorously stresses the modernity of the Gospels from the standpoint of mimetic realism and he gives a veritable explication de texte, even though the original text of Mark, or even a translation of it, is not provided. This is quite contrary to the practice of Auerbach elsewhere in the book. He would probably have justified this omission on the grounds that the gospel is really a non-literary text, a religious text. From Auerbach’s own standpoint, the difference between the two is questionable.

I will now go back to the text of Peter’s denial in order to investigate further its relationship to mimesis. After Jesus had been arrested, the disciples fled in all directions, but Peter alone or, according to John, Peter and another disciple, followed at a distance right into the courtyard of the High Priest’s palace, and, I quote: “there he remained, sitting among the attendants, warming himself at a fire.” John says that “the servants and the police had made a charcoal fire, because it was cold, and were standing round it warming themselves.” And Peter too “was standing with them, sharing the warmth.”

The text shifts to inside the palace, where a hostile and brutal interrogation of Jesus was taking place. Then we shift back to Peter and, again I quote:

Meanwhile Peter was still in the courtyard downstairs. One of the High Priest’s servant girls came by and saw him there warming himself. She looked into his face and said, “You were there too, with this man from Nazareth, this Jesus.” But he denied it: “I do not know him,” he said. “I do not understand what you mean.” Then he went outside into the porch; and the girl saw him there again and began to say to the bystanders, “He is one of them,” and again he denied it.

Again, a little later, the bystanders said to Peter, “Surely you are one of them. You must be; you are Galilean.” At this he broke out in curses, and with an oath he said: “I do not know this man you speak of.” Then the cock crowed a second time; and Peter remembered how Jesus had said to him, “Before the cock crows twice you will disown me three times.” And he burst into tears.

Auerbach makes some shrewd comments on that text: “I do not believe,” he writes, “that there is a single passage in an antique historian where direct discourse is employed in this fashion in a brief, direct dialogue.” He also observes that “the dramatic tension of the moment when the actors stand face to face has been given a salience and immediacy compared with which the dialogue of antique tragedy appears highly stylized.” It is quite true, and I am not averse to using such words as “mimesis” and “mimetic realism” to describe the feeling of true-to-life description which is created here, but I do not think that Auerbach really succeeds in justifying his use of the term “mimesis.”

Careful and sensitive as he is as a reader, Auerbach did not perceive something that is highly visible and which should immediately strike every observer: it is the role of mimesis in the text itself, the presence of mimesis as content. Imitation is not a separate theme but it permeates the relationship between all the characters; they all imitate each other. This mimetic dimension of behavior dominates both verbal and non-verbal behavior. Peter’s behavior is imitative from the beginning, before a single word is uttered by anyone.

In Mark and John, when Peter entered, the fire was already burning. People were “standing round warming themselves.” Peter too went to that fire; he followed the general example. This is natural enough on a cold night. Peter was cold, like everybody else, and there was nothing to do but to wait for something to happen. This is true enough, but the Gospels give us very little concrete background, very few visual details, and three out of four mention the fire in the courtyard as well as Peter’s presence next to it. They mention this not once but twice. The second mention occurs when the servant girl intervenes. She sees Peter warming himself by the fire with the other people. It is dark and she can recognize him because he has moved close to the fire and his face is lighted by it. But the fire is more than a dramatic prop. The servant seems eager to embarrass Peter, not because he entered the courtyard, but because of his presence close to that fire. In John it is the courtyard, upon the recommendation of another disciple acquainted with the High Priest.

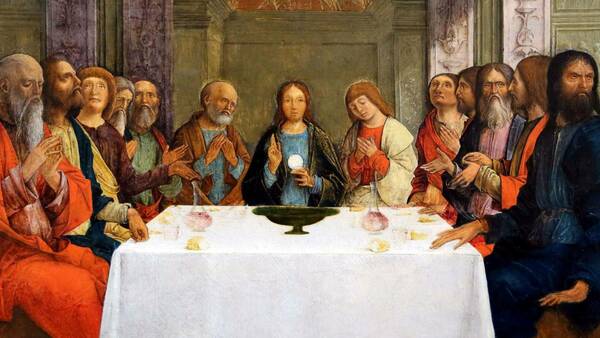

A fire in the night is more than a source of heat and of light. A fire provides a center of attraction; people arrange themselves in a circle around it and they are no longer a mere crowd; they become a community. All the faces and hands are jointly turned toward the fire as in a prayer. An order appears which is a communal order. The identical postures and the identical gestures seem to evoke some kind of deity, some sacred being that would dwell in the fire and for which all hands seem to be reaching, all faces seem to be watching.

There is nothing specifically Christian, there is nothing specifically Jewish about that role of fire; it is more like primitive fire-worship, but nevertheless it is deeply rooted in our psyches; most human beings are sensitive to this and the servant girl must be; that is why she is scandalized to see Peter warm himself by that fire. The only people who really belong there are the people who gravitate to the High Priest and the Temple, those who belong to the inner core of the Jewish religious and national community. The servant maid probably knows little about Jesus except that he has been arrested and is suspected of something like high treason. To have one of his disciples around the fire is like having an unwelcome stranger at a family gathering.

The fire turns a chance encounter into a quasi-ritualistic affair and Peter violates the communal feeling of the group, or perhaps what Heidegger would call its Being-together, its Mitsein, which is an important modality of being. In English, togetherness would be a good word for this if the media had not given it a bad name, emptying it entirely of what it is supposed to designate.

This Mitsein is the servant girl’s own Mitsein. She rightfully belongs with these people; but when she gets there, she finds her place occupied by someone who does not belong. She acts like Heidegger’s “shepherd of being,” a role which may not be as meek as the expression suggests. It would be excessive in this case to compare the shepherd of being with the Nazi stormtrooper, but the servant maid reminds us a little of the platonic watchdog, or of the Parisian concierge. In John she is described as precisely that, the guardian of the door, the keeper of the gate.

This Mitsein is her Mitsein, and she wants to keep it to herself and to the people entitled to it. When she says: “You are one of them, you belong with Jesus,’ she really means, ‘You do not belong here, you are not one of us.”

We always hear that Peter acts impulsively, but this really means mimetically. He always moves too fast and too far; but still, why move so close to the center, why did the fire exert such an attraction on him?

The arrest of Jesus has forever destroyed the community of his disciples, or so did the disciples believe, so did Peter himself believe. The disciples have fled. “I will smite the shepherd and the sheep of his flock shall be scattered abroad.” Peter had abandoned everything to follow Jesus. His Being-together was there and it was lost. This is the reason Peter answered the way he did the first time the servant girl addressed him. The question is always the same: “Are you one of them, are you with him?” That question has become meaningless. That is why Peter answers, “I do not know. I do not understand what you mean.” This is not the bare-faced lie we imagine. There is no such thing, perhaps, as a really deliberate lie. Peter does not belong anywhere or with anybody. He has lost touch with his own being.

In his state of shock, only elementary impulses are left in him. The night is cold and there is a fire; everybody turns to the fire and so does Peter. Just like everybody else at this juncture, but more than anybody else, Peter is shivering in the cold and groping about in the dark. That explains, perhaps, why he got so close to the edge of the fire, in the most visible spot. His ontological deprivation made the fire even more attractive to him than to the others. To him especially, the fire is more than a source of light and heat. By himself Peter is nothing; there is no life in him. Being means Being-together; the important thing is not the warmth as such, but the fact that it is shared with the others. John emphasizes this sharing: “And Peter too was standing among them, sharing the warmth.” Luke also gives prominence to the Being-together: “They lit a fire in the middle of the courtyard and sat around it, and Peter sat among them.”

The servant girl feels that Peter tries to share in something in which he should not share. Peter immediately understands the significance of the fire; he moves away from it but he does not leave the courtyard. He moves to a less conspicuous spot but does not really try to hide. Once aroused, however, the servant girl demands more; she has kept an eye on Peter and a second time she says: “This fellow is one of them.” In Matthew it is a second servant girl who addresses Peter the second time, but I prefer Mark’s version. The same servant girl repeats her own words, except that this time she addresses the crowd rather than Peter; she imitates herself in order to be imitated by the crowd. The first time she shows what everybody else should say to Peter, but nothing happens. The second time she gives an example of how her own example should be followed. And this time she succeeds. The bystanders repeat after her: “Surely you are one of them. You must be; you are a Galilean.”

The pattern initiated by the servant girl is one of collective pressure against Peter and the bystanders adopt it readily because it corresponds to the normal behavior of a community in the face of an intruder. Either you belong around the fire and you do not belong with Jesus or you belong with Jesus and you do not belong around the fire. No Mitsein extends to the whole of mankind or it is no longer a Mitsein in the Heideggerian sense. In order to keep a Mitsein healthy and shepherd it properly, it is not sufficient to keep together those who belong together—one must also keep out those who do not belong. Heidegger says nothing of this but the gospel text does, and it is not difficult to show that much human behavior proves the gospel right. The Being of a community is one with the exclusiveness of its Being-together. Against an intruder, it is not difficult to mobilize all those who belong together, and this is what the servant has done.

There is no lack of communication between Peter and his antagonists. They all know what is at stake. Peter has been caught stealing into the community of those who warm themselves by the fire. The servant girl loudly proclaims that he belongs with Jesus because she takes it for granted, like most people, that membership in one group is exclusive of membership in the other.

Only one Mitsein, one Being-together, is explicitly mentioned, the group of Jesus and his disciples, but two are at stake and the more important of the two at this point, even in the eyes of Peter, is the one that is not mentioned, the one which has the fire as its symbolic center. The people around the fire really say to Peter: “You pretend to belong with us but you can’t because you belong with Jesus and the other Galileans.” The bystanders imitate and repeat exactly what the servant girl has said except for this one addition: “You are a Galilean.” Matthew is even more explicit: the bystanders say to Peter: “Your accent gives you away.” The maidservant had said nothing about Peter’s accent because Peter had not yet opened his mouth. Like the people of Jerusalem, Peter speaks Aramaic, but with a Galilean accent, a provincial accent. If you do not belong with the people around you, they say that you have an accent; in other words, you speak with a difference, you cannot imitate their speech as perfectly as they imitate each other’s speech. Perfect imitation and the togetherness of being go hand in hand.

An outsider will never be acceptable unless and until his imitation becomes perfect. Mimesis is the only key that can open a closed community. A mimetic definition of culture does not result in too much openness; it does not do away with the barrier between insiders and outsiders. Only the most superficial forms of imitation are voluntary. However hard Peter tries, he must always speak like a Galilean. He is an adult and he cannot change the way he speaks. This is the reason the matter of his accent is brought up at this point. The more Peter speaks, the more he betrays his real identity. He betrays himself and, in order to counter this self-betrayal, he is forced more and more into the betrayal of Jesus.

The people around the fire are loyal servants of the Temple. They belong to the inner center of Jewish religious and national life, but they have no education and their contribution is minimal. Their pride of place resembles the snobbery one finds today in the cultural centers of our world—great universities, for instance, or world capitals. The less one can do for the place in which one lives, the more importance one attaches to living there; and rightly so, because it is the place which is doing something for one, and one feels intense disdain for the people who do not belong there. Peter senses this, and his desire to make himself acceptable increases each time he is denounced as an outsider and is rejected as such.

The dialogue between Peter and his persecutors becomes sharper and sharper; it is a form of competitive emulation or mimetic rivalry. The conflictive nature of the relationship does not make it less imitative; it is more imitative than ever. Since Peter cannot lose his Galilean accent, he must emphasize another kind of imitation. Why does he become vociferous in his denial of Jesus? His antagonists know the truth and he knows that they know. He is not trying to make himself believable or to intimidate anybody. By resorting to violence, he is not widening the rift with the people around the fire: he is trying to establish a bridge. His violence is not directed against his listeners. With these people, he knows, the arrest of Jesus is equivalent to a conviction of guilt. His furious refusal to have anything to do with Jesus amounts to a rejection symmetrical to the one of which he himself is the object. Peter is an imitator once more. What these people are doing to him, he is doing, too; but he is doing it to Jesus in the hope that all will be able to unite and be reconciled against Jesus, that the togetherness which is denied to him will generate the common victimization of Jesus. What he really means is: “We have the same enemy and therefore must be friends.” The Being of a community does not consist merely in loving together but in hating together as well. The only imitation which is not superficial and which is accessible to an outsider like Peter is this togetherness of hatred, mimetic scapegoating. Peter does not really deny his past, but he tries to atone for it and to present himself as a new man.

Peter’s denial is part of the Passion of Jesus; it is presented as an episode of this Passion. It is part of a larger process that also depends on mimetic relationships between the various actors. These may mimetically disagree at first, but then are mimetically reconciled against Jesus; the whole process tends, therefore, to a mimetic unanimity which is never achieved in the episode of Peter but which is achieved in the case of the Passion as a whole. The jealousy and fears of the religious authorities, the caprice of the crowd, the political prudence of Pilate when he yields to that caprice, all the various sentiments of the people involved amount to variations of mimetic desire or contagion that finally converge and unite in a unanimous assent to the Crucifixion.

Most anthropologists and historians of religion are convinced that the Gospels are nothing but the accompanying text, or the founding myth, of a new sacrificial cult. All stable forms of association among men are cemented in blood. Either institutionally, in religious communities founded on sacrifice, or spontaneously, men are irresistibly drawn into common victimization in order to preserve or to establish a bond of unity between them.

On this point, the most archaic theologians see eye to eye with the philosophers of the Enlightenment and their heirs, the contemporary social scientists. On this point there is a perfect agreement between the most traditional Christianity and the modern belief that there is nothing truly original in Christianity, that it is a sacrificial religion similar to all others. This unanimity is impressive, but the text we have just read raises the most serious doubts regarding the sacrificial reading of the Gospels. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century anthropologists have done a superb job of showing that the central event in the Gospels, the death and resurrection of Jesus, is really the same or pretty much the same as in most sacrificial myths. They have proved their point convincingly, I believe; but far from excluding an unbridgeable difference between the two, this identity of the central event opens up a possibility which they have missed. The Passion is really a sacrifice, and so is Peter’s denial; it is not a fully effective sacrifice but it is an attempted sacrifice. One point, however, has been overlooked, and this point is crucial. Sacrificial cults are interpreted and performed from the standpoint of the sacrificers—in other words, from the standpoint of the actors in the Passion or, in the case of our episode, of the people who rightfully warm themselves by the fire. The primary concern of these cults is the social bond which, in our episode, is suggested by the fire, then reinforced when those who, because they truly belong there, mimetically unite against Peter. In sacrificial cults, fire, indeed, is sacred; there may be no other deity but fire itself or its heavenly counterpart, the sun. The sacrificial victim may be interpreted ultimately as a divine but is viewed primarily as a threatening outsider, a malevolent intruder who should be expelled and destroyed.

The attitude of the people around the fire and the intimations of fire worship are certainly consonant with most religious cults—we cannot be surprised to see Peter slipping back into the immemorial practice of mankind—but this practice is not what the Gospels advocate. The Being-together of Heidegger with its basis in ethnic, linguistic, and cultural characteristics is also alien to the message of the Gospels, as it is essentially pagan.

Peter’s denial is an aborted return to something both very banal and very fundamental in human culture. Either institutionally, in religious communities founded on sacrifice, or spontaneously, but always mimetically, men are irresistibly drawn into such forms of victimization in order to establish or to preserve their social bond.

Peter denies his Lord in order not to be derided and persecuted, in order to avoid a fate similar to, if less tragic than, that of Jesus. It is a well-known Christian idea, indeed, that we all inflict more suffering on Jesus in order not to suffer with Him, in order not to be crucified with him. Peter’s denial is a literal illustration of this theme.

Peter’s denial makes a good deal of sense in the context of initiation rituals. An initiation often consists of an act of violence by the future initiate. The young man is supposed to prove his worth to the tribe by killing a dangerous animal or even a man, and his victim is perceived as the enemy of the entire group. In the cultures of headhunting, for instance, the victim normally belongs to the alien group from which such victims are regularly drawn; between this group and the group which the sacrificer will now join, thanks to the mediation of this sacrifice, a state of permanent hostility prevails. Initiation into the rival group is exactly the same process, with the two groups inverted.

To deny Jesus in the sense of Peter’s denial means to sacrifice him. When Jesus accepts death, therefore, he cannot be performing a sacrifice, at least in the same sense. Jesus accepts death in order never to behave like Peter and the other people around the fire. Jesus dies to put an end to sacrificial behavior; he dies not to strengthen closed communities through sacrifice but to dissolve them through its elimination. When the death of Jesus is presented as sacrifice, its real significance is lost. The sacrificial definition makes it impossible to distinguish Peter’s denial and Peter’s confession of faith. The definition suppresses all differences between the perspective of the persecutors and the perspective of the victims. Most victims, of course, are only would-be persecutors, like Peter. Jesus, therefore, is a very special victim who refuses not only the vicious circle of mimetic violence but also the breaking of that circle through the mimetic violence of unanimous scapegoating. Regarding the relationship of sacrifice and victimization, social unity and victimization, the Gospels spell out a truth which is nowhere else to be found.

An essential component of that truth, of course, is the mimetic nature of victimization and the mimetic nature of the human relations that lead to victimization. I believe that the text of Peter’s denial is highly characteristic in that respect. The amount of redundancy or repetition in it is astonishing. Everybody is doing the same thing, everybody is saying the same thing. Peter is told the same thing three times, the first two times by the servant girl alone, the third time by the people around the fire. Peter, too, imitates himself as well as the others; except for its increasing violence, his denial remains the same every time. And yet this repetition is not mere rhetoric: the text manages to sustain our interest, it teaches us something about the mimetic nature of desire and of human relations, something no other text ever taught. Even though it is very brief, this text reveals three modalities of mimetic interaction that are found throughout the gospel. First, there is a mimesis which is one with the cohesiveness of human culture, or subculture: around the fire, everybody behaves in the same manner, everybody speaks the same words. Second, there is a mimesis of desire that is divisive and destructive of culture because it produces rivalry around an object that two or more desire; partners, co-imitators of each other’s desires, who cannot share or do not want to share: the servant girl does not want to share the warmth of the fire with Peter. If one looks carefully at Plato’s theories of mimesis one will see that these first two modalities are present in his work, but they are hopelessly confused and, as was shrewdly pointed out by Jacques Derrida, Plato contradicts himself in regard to mimesis. Sometimes he sees it as a factor of social order and sometimes as a factor of disorder, with no criteria of distinction between the two; as a result, Plato’s view of mimesis cannot be made systematic and coherent.

The problem is not with the passage from the integrative mimesis to the disintegrative mimesis: the mimesis of social order becomes degraded into the mimesis of desire and rivalry. Many dialogues of Plato, and above all, The Republic, illustrate that degradation. The problem lies in the passage from disorder to order. There is nothing in Plato that can explicate the genesis of order, the transmutation of mimetic rivalry into the functional culture. There is no intelligible transition between the two; that is why, in Plato, the genesis and perpetuation of the social order is a transcendental and metaphysical mystery, just as obscure as the religious mystery in primitive mythology and ritual. The revelation of the social mechanism that transmutes the bad mimesis into the good mimesis and into order is a purely biblical discovery; it occurs in Chapter 53 of Isaiah and elsewhere in the Bible, but it is most explicit in the Gospels. It is the mimetic mechanism of unanimous victimization; it is the mechanism which Peter tries vainly to reactivate with Jesus as the victim in the text I have just read.

The Gospels are the first texts in which this mechanism is fully revealed as a human and purely mimetic phenomenon rather than as a transcendental mystery. It is true, of course, that transcendence is present in the Gospels, but it does not rest on that mechanism, which is fully demystified in the sense that the representation of the victim as a culprit is deconstructed and the mimetic genesis of this collective representation is revealed.

Auerbach’s view that Peter’s denial is much more mimetic than all ancient literature is an indirect acknowledgment of the mimetic content I have just described, of the Gospels’ gigantic but still misunderstood advance beyond the platonic concept of mimesis. The best estheticians of mimetic realism, like Auerbach, sense this but are unable to explicate what they sense. In their relationship to the gospel they are completely tongue-tied, like the father of John the Baptist; they try to comprehend a view of mimesis enormously superior to that of Plato, from the standpoint of an inferior view, a view that is an impoverishment of the platonic concept. In Plato, the darker and more sinister side of conflictive mimesis is unaccounted for, but it is present, whereas in Plato’s successors, beginning with Aristotle, mimesis has been totally divorced from desire and reduced to the sheepish and bland porridge of esthetic imitation.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted here from Cynthia L. Haven’s selection of Girard’s writings entitled, All Desire is a Desire for Being (137–149), thanks to the generous permission granted by Penguin Random House UK and the University of Notre Dame’s Religion & Literature, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.