The “traditionalists” among conservative Christians are surprised when we show them how relatively modern and extremely limited is the form of Christianity that they wish to conserve, and what enormous intellectual and spiritual wealth resides in much older traditions of the church; suffice it to recall the desert fathers, the Greek patristics, the negative theology of Dionysus the Areopagite, the medieval mystics, etc.

Maybe what some called secularization and the decline of religion and others “the death of God” marked the beginning of theology’s inability to respond creatively to the changing picture of the world and mankind on the threshold of modernity, having exhausted itself with interdenominational conflict. Theology in those early days of modernity adopted unthinkingly, inadvertently—and hence uncritically—modernity’s division of reality into subject and object and to a great extent adapted the medieval dichotomy of the order of nature and the order of grace, the natural world and the supernatural world, to that new division. Emphasis on the “objectivity” (now the antithesis of subjectivity) of God and the order of grace also meant externalizing him and became a fatal step into the abyss of atheism.

A purely “objective” God (emphasis on transcendence at the expense of immanence) is a God distinct from man. This under- mines and even displaces the mystics’ experience of God dwelling in man. It is then quite understandable that at a time of growing awareness of human grandeur and power, people regard that kind of “external God” as competition and an obstacle to their emancipation (whereas previously he was simply an obstacle to human pride)—and eventually as an enemy to be eliminated.

When the Enlightenment’s new concept of nature and natural order became universally accepted, “natural” began—naturally— to be regarded as a synonym of “real.” The “supernatural,” including the modern theological concept of God, then paradoxically found itself in the dubious sphere of purely private opinion, or worse still, in the dusty cupboard of discarded children’s toys and fairy tales, among the elves and gnomes. There was no place for the objective (external) supernatural in the new naturalistic image of the world, in the new concept of objectivity. “Nature” now designated the aggregate of what was perceptible by the senses, measurable and clearly apprehended by reason; it was granted a monopoly on “reality” and “objectivity.” Anything that fell outside those categories was “unreal.” Old religion started to be regarded as a purely subjective (private) matter; the radical wing of the Enlightenment considered it to be “superstition,” while Marxists saw it as a briefly surviving relic of a social order being led to the execution ground of history by the class-conscious proletariat.

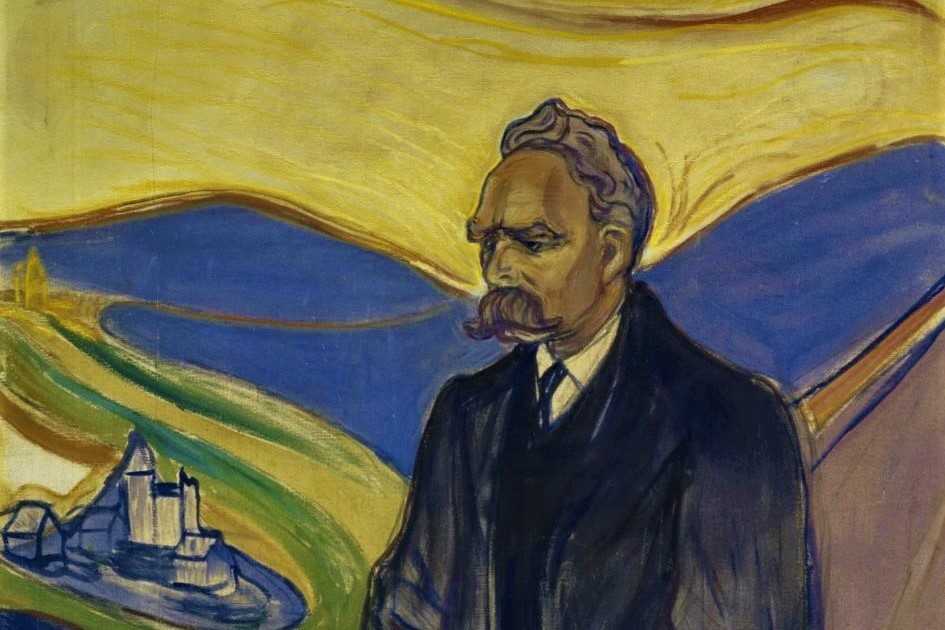

God thus becomes in the minds of “modern people” a banal god, who is only fit to serve as an ornament for certain celebratory moments, a favorite cliché of political rhetoric, a bogeyman for disobedient children, and a whipping boy for atheists, from Nietzsche, Freud, and Marx to Dawkins and Co.

The failure to take into account the consequences of the long- standing gradual replacement of the biblical God with the Aristotelian concept of god proved fateful for Catholic theology in the modern age.5 If that classical philosophical concept of god had been seen as simply a metaphor and greater consideration had been given to the richly variegated biblical images of the Lord speaking both in a tempest and in the stillness of the heart, maybe a the- ology drawing on the mutual tension of biblical images and philosophical concepts might have avoided both the rigidness of neo- scholasticism and biblical fundamentalism. It would then have been obvious that God is neither “solely objective” nor “solely subjective” and that thinking about God cannot be tied to the artificial object-subject matrix. A god who is “solely objective” and a god who is “solely subjective” is a banal god; both fundamentalism and fideism are blind alleys of Christianity. The occasional passionate protests—the most striking of which was Pascal’s cry in his Memorial, “‘God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob,’ not of philosophers and scholars . . . God of Jesus Christ”—remained ignored. It was not until Kierkegaard, Barth, Bonhoeffer, and “death of God” theology that Christian theology came to realize that the death of God announced by Nietzsche and others was the death of the banal god of modern times and that that event could be liberating for Christian faith. But that liberation is far from constituting any sort of triumph but is rather a challenge to seek, to engage in intellectual activity, to “launch out into the deep.”

Nicholas Lash speaks about the “end of religion.” By this, he means of course the end of one historically conditioned form of Christianity, which established itself particularly at the time of the Enlightenment, namely, religion as one sector of culture alongside others. But he mentions what, in his conviction, does not end, and that is faith, hope, and love. And I shall take that as my inspiration here.

Our era is becoming accustomed to a new designation, the post-secular age. Secularization was the slogan of the modern age; postmodernism transcends that phase. As we enter the coming post-world, the world of multiple “posts,” it is time to set aside the paradigm of secularization along with other inventions of the Enlightenment thinkers. Postmodernism represents an interesting and attractive proposition for theology, and it is therefore not surprising that many theologians have seized on this proposition.

Editor's Note: this excerpt comes from I Want You to Be: On the God of Love (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2017), 57-59. Reprinted by permission of the author and University of Notre Dame Press.