When we speak about the “Catholic Imagination” we usually speak about how it relates to the arts, particularly literature. Which is only right. The notion of a specifically Catholic imagination did not originate with theologian David Tracy’s The Analogical Imagination, much less with sociologist Andrew Greely’s later book titled The Catholic Imagination. It began really in the late 1940’s and early 50’s with essays like poet Alan Tate’s “The Symbolic Imagination,” Flannery O’Connor’s lecture on Mystery and Manners at Notre Dame in 1957, which I was fortunate enough to attend, and books like William Lynch’s masterful, Christ and Apollo, published in 1960.

Nonetheless, there can be no denying the culture-forming power of religion—whether it be on the sensibilities of individual artists or on the ethos of whole communities, especially in those regions of the American South where, it often seems, there are more Baptists than there are people.

Either way, we are talking about religion’s capacity to shape, partly in a preconscious way, how we structure our experience of the world, and our hopes and aspirations within and beyond it. That is what I mean by the religious imagination.

My point is this: whether you are an artist, a scholar or a journalist, merely curious or earnestly interfaithful, you cannot understand another religion, even another Christian tradition, unless you go beyond doctrine and practices and fully engage with that tradition’s religious imagination. History, I submit, bears this out.

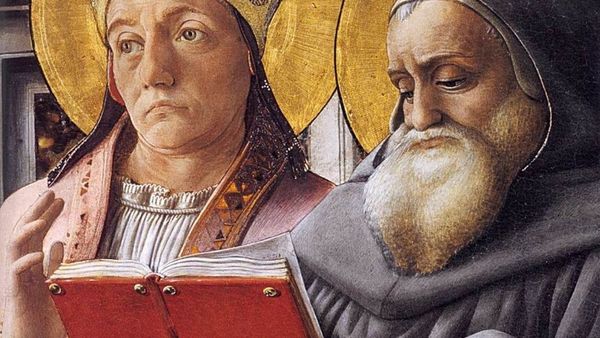

In his class study, The Waning of the Middle Ages, Johann Huizinga argues that one of the reasons for the Protestant Reformation was the late medieval imagination, which brought the realm of Christ and the saints into smothering proximity with ordinary daily life, and the Medievals’ concomitant habit of “crystallizing” religious thoughts into images. From this perspective, the Reformation was a reaction that put God and the things of God at greater distance from this fallen human world, thus allowing more space for human freedom and folly, and a rejection of images and all other visual manifestations of heavenly presences in favor the preached word. As you can see, Huizinga’s historical observations align well with David Tracy’s distinction between the analogical imagination typical of Catholics and the dialogical imagination typical of Protestants.

Another touchstone text for me as I tried to understand and communicate different religious imaginations to readers of Newsweek is Erich Heller’s The Disinherited Mind, In one essay, Heller points to the famous dispute between Luther and Zwingli over the Eucharist: was the presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine real, as Luther contended, or symbolic, which was Zwingli’s position? In Heller’s view, Zwingli’s stand signaled a hugely consequential transformation in the Western sensibility, one in which the real was no longer symbolic and the symbolic had become “merely” symbolic. For Heller, this amounted to “a radical change . . . in that complex fabric of unconsciously held convictions about what is real and what is not.”

Returning to the present, let’s consider Pentecostalism, the world’s fastest growing form of Christianity. Born in the USA, and barely a century old, Pentecostalism strongly resembles late Medieval Catholicism, as Huizinga describes it, in that both exhibit a religious imagination in which God and the devil intervene for good or ill directly in human affairs. There is no space in the Pentecostal imagination for a concept of natural law, and the laws of physical nature are malleable to prayer—as anyone knows who has watched Oral Roberts or Pat Robertson on television.

Robert Orsi, who teaches religious studies at Northwestern University, has defined religion as “the practice of making the invisible visible,” and argued that the proper focus of religious studies should therefore be on the “sacred presences” that form the bonds “between heaven and earth.” His approach certainly accords well with the Catholic and Hindu religious imaginations, but also with Mormonism, though not in so obvious a way.

For me, the Mormon imagination is best encountered in the vision of the afterlife elaborated by the Prophet Joseph Smith. I did not notice this until a Mormon friend told me the story of a former Prophet of the church who had a major problem to solve and prayed repeatedly to his deceased predecessor for advice but without response. Finally, an answer came back with this apology: “I’m sorry I didn’t answer sooner, but I’ve been so busy up here.”

Anyone who has close friends among the Latter Day Saints quickly realizes that the church keeps its members very busy because its ethos is built on work. There is no room in the Mormon way of life for the contemplative calling. Not for nothing is Utah called the Beehive state.

Joseph Smith’s genius, though, was to answer the problem of death by imagining the next life as a continuation of this one, a place where Mormon missionaries would still be active, where families would continue to expand and cohere, and where those admitted to the highest of the heavenly kingdoms would work in order to progress to the status of divinity like the Heavenly Father and Mother.

Thus, the Mormon imagination is neither analogical nor dialogical but literal, as evidenced by the Mormon murals in the church’s Salt Lake center, or by the dioramas on display in it New York City church center, both of which make the Soviet realism of the 1930 look like Cubism.

But what can we say about the Protestant Imagination? It would help if Protestants themselves would tell us. A recent Google search turned up no conferences exploring the Protestant Imagination and only one book with that phrase in the title.

It would seem particularly difficult to discern the religious imagination of Reformed Christianity since the iconoclastic John Calvin and his fellow reformers “stripped the altars “ of statues, figured stained-glass windows, of symbolic vestments and any other visuals suggestive of sacred presences mediating between heaven and earth.

Thus, one cannot imagine New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art staging a show called “Heavenly Bodies: From John Calvin to Billy Graham,” like the recent one it staged on Catholic visual culture. Yet I would argue there is a palpable religious imagination to be discerned, even in preachers dressed in basic Baptist threads. Let me tell you a story.

In 1972, Newsweek decided to put Billy Graham on the magazine’s cover for the first time and so I, as the writer, flew out to Los Angeles to interview him. We met in a television studio where Billy was reviewing a videotape of a recent crusade he held with President Nixon as his guest. I watched Billy watching himself preach and then asked him what he was experiencing, thinking perhaps he was second-guessing his doppelganger on the monitor. But that was not the answer I got.“I get so engrossed, Ken, I don’t think of the man on television as me,” Graham said. “I think of him as another person speaking because the spirit of God begins to speak to me through him.”

That was another "Aha!" moment for me. For Graham and for those who heard him, his performance resonated as a verbal sacrament, one in which “the Word Made flesh” becomes through the medium of his own voice, “the flesh made words.” In sum, it seems to me that we cannot fully appreciate the Catholic imagination unless we understand the Protestant imagination in its various forms. The problem, I believe, is that we have been looking in the wrong places. We do not need eyes to see. But we do need ears to hear.

Protestant Christianity, particularly in its Calvinist forms, is essentially an oral-aural experience. That experience takes its most expressive form not just in preaching but, above all, in its music. Indeed, I suggest that a robust taxonomy of the American Protestant imagination could be gleaned from a deep immersion in the music it has produced, from the psalmody of the Puritans through the great Methodist hymns, especially those of Charles Wesley, to The Old Rugged Cross and that iconic celebration of the revivalist experience of salvation, Amazing Grace.