The question of immigration is almost always framed in terms that make it appear easier than it actually is. A reliance on personal stories and captivating images on both sides of the debate fails to account for the complexity of the challenge, or, better, the array of challenges, involved in dealing with migration. The policy discussion in the United States is remarkably convoluted, and yet it is also problematic to believe that somehow, if we just set “politics” aside, everything would fall into place.

One thing that would help is the ability to step back and try to gain a comprehensive moral standpoint on the problem. A common standpoint is that of hospitality, of “welcoming the stranger.” There is no doubt that the biblical narrative is filled with stories and even laws enjoining such hospitality. One could imagine the Bible giving support to a “preferential option for the migrant.” However, the image has two significant limitations.

One is that it gives little guidance as to how far hospitality extends. True, the Gospel characteristically rejects any limits on such matters, but it takes little effort to see that, in our daily lives, extensions of hospitality involve characteristic judgments of prudence about when, how, etc. Two, the theme gives us little sense of why the hospitality is required. The injunctions in the Hebrew Bible indicate that such hospitality is due because “you too were once aliens in the land of Egypt” (Lev 19:34)—a reason that has particular resonance with America’s identity as a nation of immigrants. Yet, this image can then drag us back into the weeds of details over differences between historical eras and possibilities, not to mention ignoring the equally-biblical commands given to the Israelites to destroy the Canaanites occupying the Promised Land.

Without prejudice to the image of welcoming the stranger, I would suggest that Catholic Social Teaching gives us a more robust, deeper image that better addresses especially the long-term pathways needed by most migrants: the image of every life as a vocation. Moreover, this image builds on the strong foundation of the dignity of every human person, fleshing out more clearly what is at stake in recognizing just migration as integral to building a genuine culture of life.

It was Pope Saint Paul VI who introduced this image of life as a vocation, in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio. That encyclical constituted a new turn in Catholic Social Thought, moving from its original focus on justice within industrializing nations to a focus on international human development. Subsequent popes reaffirmed this turn, with both John Paul II and Benedict XVI issuing “anniversary” encyclicals commemorating and extending this teaching. While the focus of these documents has typically been an analysis of the international economic order of the time, the distinctly inter-national character of immigration suggests a further look at the teaching’s foundation.

Paul VI, as is well-known, called for “integral” development—development that is not purely economic or technical, but rather one that “has to promote the good of every man and of the whole man” (§14). Less well-known is the next paragraph, which in fact provides the real description of what this means:

In the design of God, every man is called upon to develop and fulfill himself, for every life is a vocation. At birth, everyone is granted, in germ, a set of aptitudes and qualities for him to bring to fruition. Their coming to maturity, which will be the result of education received from the environment and personal efforts, will allow each man to direct himself toward the destiny intended for him by his Creator (§15).

This idea of “fulfillment” certainly culminates in “salvation,” but as Paul makes clear in subsequent paragraphs, it is also a matter of a “humanism” that includes the development of capacities for education and culture, freedom from “social scourges,” participation in forms of social cooperation, and peaceableness. Notably, Paul says it is not a matter of “increased possessions” leading to a “stifling materialism” (§18-19), but rather the movement toward “the possession of necessities” and the “turning toward a spirit of poverty” (§21).

When I teach this passage, I invite students to see that what Paul is describing is basically the sort of thing that every middle-class parent in a developed country wants for their children: not simply a marginal life of survival, but a life where basic survival needs have been secured, making possible a development of talents and gifts in ways that ultimately contribute to the society. Again, not simply to the achievement of personal wealth and success! And Paul’s point is to help us see that this will for fulfillment really is God’s will for human life—but for every human life, not just that small percentage born into economically-stable situations in rich countries.

This is of course why a genuine culture of life cannot simply be against abortion, but must be pro-child in a variety of ways. What we want in the culture of life is a culture not of survival, but of flourishing. And while there can and will be debate about how to help individuals fulfill their vocation, we should recognize that already in the United States we have extensive investments in support systems for children (most especially our education system) that are of the sort Paul VI describes. Granted, these supports could be improved, particularly insofar as they perpetuate inequities. Nevertheless, they are there, and Paul does not think that social structures alone can guarantee the fulfillment of a vocation. He is clear—possibly too clear, if that is possible—that “each one remains, whatever be these influences affecting him, the principal agent of his own success or failure” (§15). Thus, we can say, not perfectly but not erroneously, we recognize each life as a vocation.

Each American life. It is here where Paul VI’s perspective becomes illuminating of the human dignity demands of current forms of migration. In the context of the US southern border, there has been a dramatic shift over the past few years, a shift that has much to do with why the situation is now (correctly) described as a crisis. A recent comprehensive study by the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute provides outstanding perspective.

For many decades, the vast majority of migrants were adult males, traveling alone from Mexico, seeking work. Especially during the Bush and Obama administrations, significant advances were made in border enforcement and management of these cases—significant enough that border apprehensions dropped substantially: from 1.6 million in 2000 to just over 300,000 in 2017. However, at the border today we find a different picture. The majority of migrants are traveling in family units, fleeing the “Northern Triangle” countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Moreover, the numbers (especially in 2019) have been increasing rapidly, with apprehensions likely to top 1 million for the first time in well over a decade.

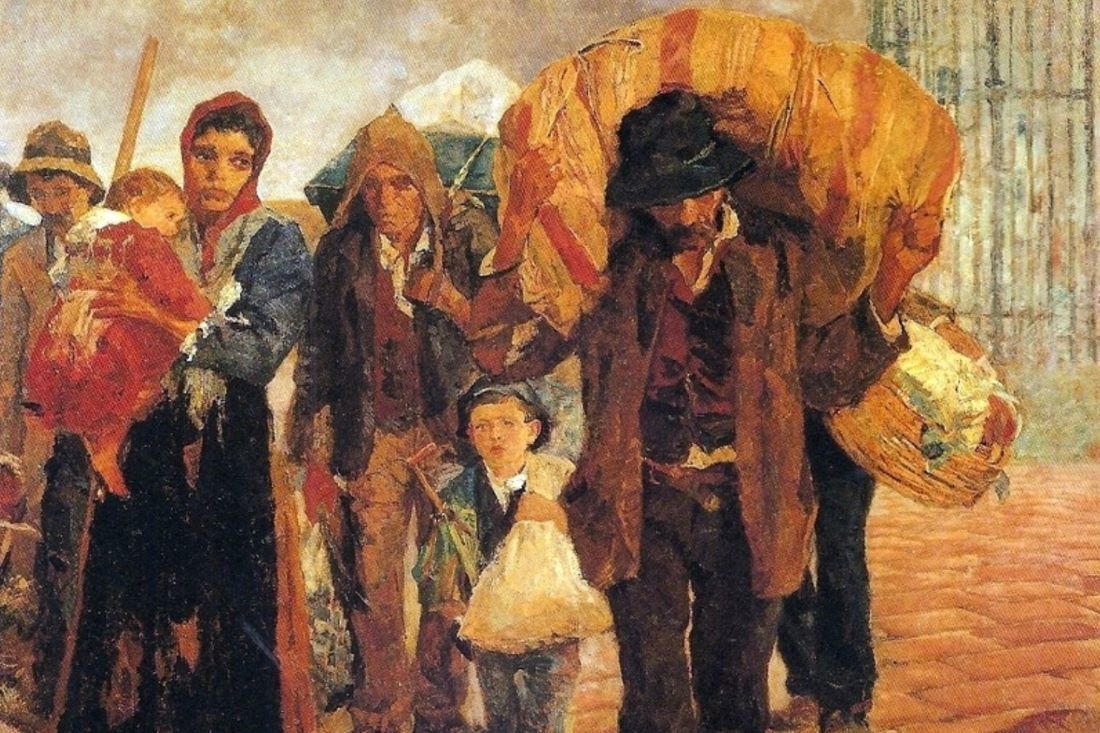

Why does this matter? Let us put ourselves imaginatively in this situation. You face a very long journey through a sometimes-violent country. You likely have to pay someone a considerable sum of money, something like a year’s average income, to facilitate your travel. And instead of a male traveling alone and wiring money back home, you instead risk the trip with the whole family unit.

If you are like me, you should be thinking, things must be pretty desperate. And they are pretty desperate. Guatemala and Honduras in particular are less developed countries than Mexico. For example, while one 2017 estimate of Mexico’s unemployment rate is 3.4%, Honduras’s is estimated at 22%. Their populations are more likely reliant on subsistence agriculture, living in rural areas. They are living through a years-long drought, one so bad that, according to a U.N. source, over 80% of the staple crops of maize and beans were lost in 2018 in Honduras. They are considerably behind Mexico in developing other internal opportunities for work. And none of this is to mention their sky-high crime rates, aggravated by gangs and government corruption. According to Ashley Feasley, the Director of Policy for Migration and Refugee Services for the USCCB, interviews show that migrants often try to relocate multiple times within their home countries before making the attempt to come to the United States.

Although individual stories cannot encapsulate the many and diverse circumstances that drive migration, the story of Eduardo, his wife Karen, and their daughter Kiara helps us grasp the complex realities of economic precariousness, violence, and corruption that so many in these countries face. According to the Diocese of Laredo, Eduardo was a truck driver in Honduras, whose truck was stolen by thieves who held him and his co-workers captive before releasing him. Eduardo did what we would expect anyone to do: filed a police report. But this law-abiding action resulted in retaliation:

The criminals pursued him at his home, threatening him with violence. Eduardo and Karen decided to sell everything they owned and choose to flee the life they knew. By the time they reached Guatemala, their daughter had caught the stomach flu which tempted them to return. Borrowing a phone, Eduardo spoke with their neighbors only to learn that five hours after they fled, their former home was attacked in a drive-by shooting. “That’s when we knew we couldn’t go back,” Eduardo said gravely.

Indeed, these simply are not the conditions that support a recognition of every life as a vocation. Thus, we need to recognize that what immigrants are seeking is simply what Paul VI insists is “the design of God”—the fulfillment of their life as a vocation that allows for the development of their “aptitudes and qualities.” For Eduardo, this may merely mean working hard as a truck driver, freed from the threat of violence. But for his daughter, it may mean the difference between life and death at a young age. And it certainly means being able to grow up in circumstances that enable the development we all want for our children.

This idea of every life being a vocation is critical to the pro-life witness. When pro-life advocates show the baby developing in the womb, or suggest that “God calls each by name,” or wonder about the loss of the “next Einstein,” it means to suggest to us not simply a basic survival right, but a sense that there is a potentiality to a life that is so great and tremendous, of such value, that it is unthinkable to reject it. But how many Einsteins fail to develop amidst the hunger and violence of these countries? This too must be a fundamental dignity question. Because every life is a vocation.

Moreover, the recognition that every life is a vocation is connected to the great theme of Vatican II’s Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium: the universal call to holiness. This is the idea that “all the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status, are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity; by this holiness as such a more human manner of living is promoted in this earthly society” (LG §40). This universal call is not merely a personal summons to piety, but a summons to solidarity through which all have the opportunity to live in “a more human manner” and grow in holiness.

This emphasis on universality is in part an overcoming of the idea that only some in the Church (e.g. clergy and religious) are called to the full stature of holiness. But it is also a consequence of Lumen Gentium’s leading image of the Church, as a “sacrament” of “the unity of the whole human race” (LG §1). The Church’s own communal life is meant to function as an effective prefigurement of God’s desire for all nations to live as one, in unity and peace. The Church’s form of unity is not a single world order imposed by the elite and powerful, whether economic or political, but a genuine unity that enables the full development of each person. Paul VI makes this clear enough when he that “the goal we must attain” is “world unity, ever more effective” that “should allow all peoples to become the artisans of their destiny” (PP §65).

It is also the theme Benedict XVI sounds when he argues that globalization calls for “a person-based and community-oriented cultural process of worldwide integration that is open to transcendence” (Caritas in Veritate §42). Like Paul, Benedict seeks a natural solidarity that is only possible and is ultimately crowned by the supernatural hope of the unity of the human race, a hope for a salvation that is “social,” as outlined in Benedict’s Spe Salvi. Sadly, though predictably, so many secular attempts to promote human unity are actually anti-life. For example, forms of economic globalization often happen at the expense of workers and families, both in developed countries and in poorer nations. Global political elites suggest that the full equality of women in society depends upon the liberty to destroy pre-natal life. The unity the Church seeks is a unity in Christ, which is a unity in which each person is a vocation.

Two things should be noted about the framework suggested here. First, it does not easily translate into specific policies, not least because it assumes, from cradle to grave, a supernatural solidarity within which we consider the lives of both natives and migrants. This alternative cuts both ways politically: secular programs of cosmopolitan multiculturalism lack this background as much as secular programs inspired by inappropriate nationalism. The limits of this polarized debate need to be seen in terms of the promotion of false solidarity, each of which subtly ignore the idea that every life is a vocation.

Cosmopolitanism often involves unjust distributions of the actual burdens involved in migration, preaching solidarity while letting the day-to-day impacts be borne by the sacrifices of others; nationalism too often rests on a sense of ethno-superiority, as well as many economic misconceptions about the impacts of migration. Moreover, the experience of forced migration is not generally the most desirable option for living out one’s life as a vocation: the development of the home country is, as has been the consistent emphasis in Catholic social teaching since Populorum Progressio. The real pro-life choice is not whether to help migrants or not; it is how we should we helping migrants, rather than ignoring their obvious needs to develop their lives as Paul VI indicates God wills human lives to develop!

Thus, while discussions of policy structures are more necessary than ever, especially in terms of assisting development and stable governance in sending countries, the present crisis should call upon the Christian churches in a special and unique way to demonstrate that manifesting welcome signals a deeper conviction about God’s unique call to every person to find flourishing. When Paul VI starkly states that “the world is sick” (PP §66), he then points toward the only hope: “the dynamism of a world which desires to live more fraternally” that “is, even unawares, taking slow but sure steps toward its Creator” (PP §79). This recovery of the sense of the Creator is at the core of the fight for life. And, as Paul saw so well, it also should be at the core of the fight for the lives of others, especially migrants facing social situations of danger and despair, so that each life might be able to respond to the call given by that same Creator.