Senator Adam Sunraider has a secret. Sunraider’s secret is as audacious as could possibly be imagined: the race-baiting white politician is at least partially black. Raised by a black Baptist preacher and brought up assisting in the reverend’s evangelical tent revivals, the senator formerly known as Bliss has been concealing his ambiguous racial identity for all of his professional life.

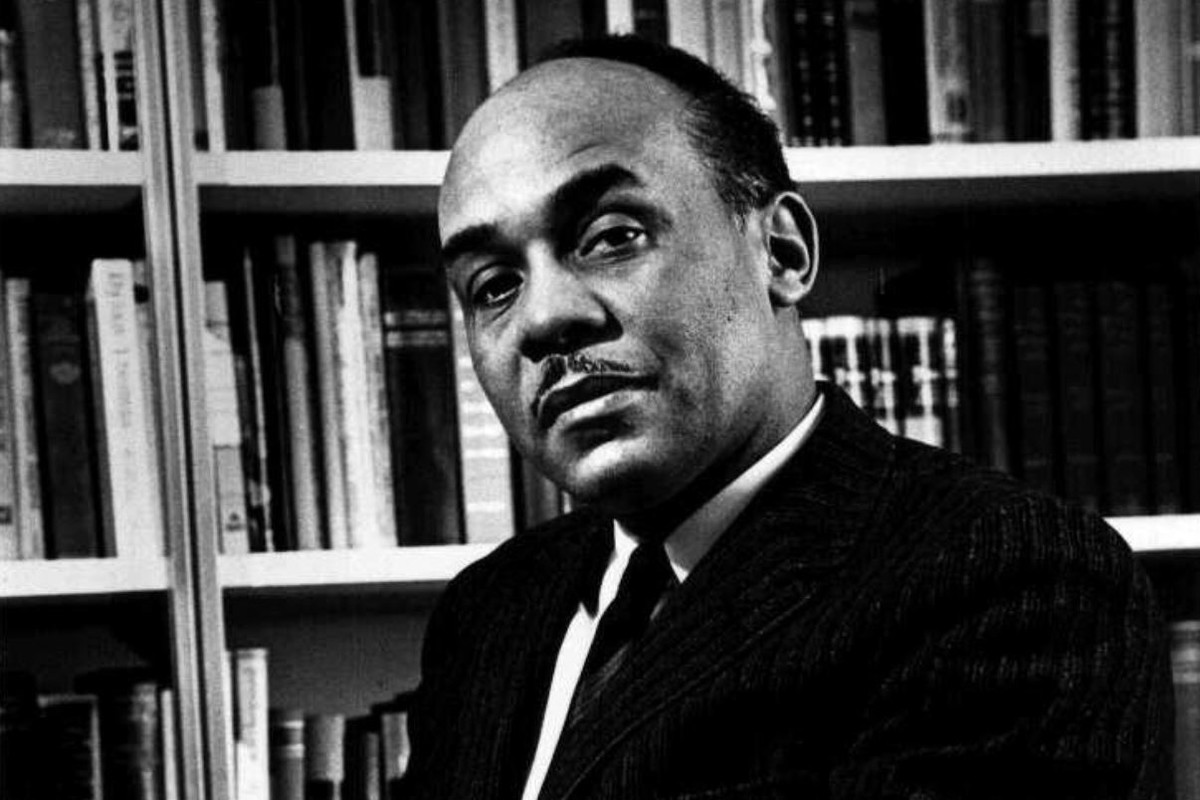

This is the premise of Ralph Ellison’s Juneteenth, the unfinished second novel project posthumously cobbled together from the author’s notes and manuscripts. The follow-up to the National Book Award-winning Invisible Man, Juneteenth unfolds under the shadow of a lynching—the reverend’s brother was brutally murdered under suspicion of impregnating Sunraider’s white mother—and was intended, Ellison said, as “an anguished attempt to arrive at the true shape of a sundered past and its meaning.”

Juneteenth also has a secret. Ellison conceived of the “basic situation” of the novel in 1956, when he was meeting daily with the Kentuckian novelist Robert Penn Warren, best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel All the King’s Men. Published in 1946, All the King’s Men fictionalizes the rise of populist Louisiana demagogue Huey Long, and bears many unnoticed similarities to Ellison’s unfinished novel: staged around a political assassination, it anatomizes the way its protagonist’s increasingly self-centered ambitions drive him to weave a web of lies around himself.

In a letter to his lifelong friend Albert Murray, Ellison enthused that the budding friendship between himself and Warren was maybe the “most important thing to happen” during Ellison’s two years at the American Academy in Rome. In that time, Ellison says, Robert Penn Warren “became the companion with whom I enjoyed an extended period of discussing literature, writing, history, politics—you name it—exploring the city, exchanging folk tales, joking, lying, eating and drinking.” Their dialogue continued up to the time of Warren’s death in 1989, at which time Ellison spoke of his friend, and of a strange dream in which Warren was swimming out to sea and turned to wave at him before he disappeared, at Warren’s memorial service.

In his 1999 review of Juneteenth, Columbia University Professor Robert G. O’Meally wrote that the novel’s “central question” was simply this: “Why has the secret son turned against his black family?” For Ellison, O’Meally wrote, all Americans were “culturally black anyhow”; he consistently foregrounded the country’s tendency not just to silence its black voices, but also to deny its very own blackness, to repress something essential about itself. Of course, Ellison didn’t think that would ever work. “How,” Sunraider asks at one point in the novel, “can the light deny the dark?”

Juneteenth itself emerges out of the dialogue between a black man and a white, one of the great novelists of the black experience in America and a once-Southern Agrarian whose own attempt at exploring race relations, a 1965 book of interviews titled Who Speaks for the Negro?, looks hopelessly dated today. Ellison was aware of the irony: in a letter addressed to Warren he took great pleasure in describing the surprise of a young black reporter who had seen a picture of Penn Warren on Ellison’s bookshelf in Harlem and exclaimed, “Well I’ll be dam . . . you just never know!” Ellison promised his friend “Red” that, the next time the subject came up, he would explain “something of the intricacies of our relationship and some of the ways in which friendship transcends abstractions.”

Ellison and Warren’s friendship certainly extended to a warm regard for, and careful attention to, each other’s work. Ellison’s personal copy of All the King’s Men—now kept at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.—is thoroughly underlined and annotated. Some of the themes that caught the Invisible Man author’s eye are predictable enough: “fascism” is scribbled in the margins several times, as is “demagogue.” Warren’s novel is, after all, generally considered one of the great American political fictions, particularly celebrated for its depiction of the way populist sentiment can tip over into totalitarian practice. If there is a discernible center of gravity to Ellison’s annotation, however, it is not necessarily political: as in Ellison’s unfinished second novel, in Ellison’s marginal notes on All the King’s Men political anxiety gives way to a fascination with something that struck Ellison as even more deeply indicative of the intractable divides in American life: religion.

Neither Ellison nor Warren were practicing Christians, or professed religious people of any kind. The literary critic Harold Bloom, a friend of Penn Warren’s on the English Faculty at Yale, called Warren “probably the most severe secular moralist I have ever known,” and there is no sign that Ellison ever returned to the African Methodist Episcopal Church of his upbringing. Nevertheless, both authors’ bodies of work indicate acutely religious sensibilities: Warren described himself as a “yearner”—“I mean I wish I were religious”—and his novels and poetry collections, including All the King’s Men itself, are often prefaced with epigraphs from Saint Augustine or Dante’s Divine Comedy. Ellison, in a 1974 interview with the journalist John Hersey, identified the aim of his unfinished second novel project as the unearthing of key “undercurrents” in the “American experience”—in particular, “the way we turn our eyes away from the role religion has played in American life.”

In that same interview, Ellison developed a unique critical vocabulary for describing the crisis he identified in American culture and religiosity: “the underlying mode of American experience,” he declared, is “tragicomedy.” Because Americans are constantly attempting to forget the past, Ellison claimed, they are also always being confronted with an almost comically predictable return of past traumas: “We don’t remember enough; we don’t allow ourselves to remember events, and I suppose this helps us to continue our belief in progress. But the undercurrents are always there.”

In his essay “The World and the Jug,” Ellision defines the appropriately tragicomic way of looking at the world in terms of “the uneasy burden and occasional joy of a complex double vision.” In this piece, he associates “double vision” specifically with the black experience of slavery and segregation, which made it possible for black Americans, in Ellison’s view, to “suffer the injustice which race and color are used to excuse . . . without losing sight of the humanity of those who inflict that injustice.”

Ellison also clearly defines the sensibility he sees as opposed to, and threatening to displace, the “tragicomic.” In “Change the Joke and Slip the Yoke,” he skewers “the white American’s Manichean fascination with the symbolism of blackness and whiteness,” which finds expression in “his general anti-tragic approach to experience.” This “basic dualism of the white folk mind,” Ellison believes, tends to issue in a peculiar kind of cyclopean monomania, like that of Invisible Man’s glass-eyed Brother Jack: everything must be either good or evil, black or white, human or inhumane. Sooner or later there is simply no room at the inn for the tragicomic—and, for Ellison, essentially human—admixture of good and evil, bitter and sweet, suffering and forgiveness.

One particular marginal note in Ellison’s copy of All the King’s Men proposes an even more specific vocabulary for describing this complexity-flattening, “anti-tragic,” “Manichean”-American dualism. Next to a passage in which Warren describes “the man of idea” and the “man of fact”— the novel’s narrator/researcher Jack Burden and its Huey Long stand-in, Willie Stark, respectively—as “doomed to try to use the other and to yearn toward and try to become the other, because each was incomplete with the terrible division of their age” [italics replace Ellison's underlining here], Ellison draws a line down the margin of the paragraph and writes beside it: “Moral . . . Calvinism.”

Of all Ellison’s annotations of All the King’s Men, this is the one that makes the most decisive critical intervention, and most clearly indicates the Invisible Man author’s own idiosyncratic interests. As with “Manichean . . . dualism”—which refers directly to a school of ancient thought most widely known now only through Saint Augustine’s conversion away from it—Ellison’s note invokes a specifically religious-historical framework for understanding the themes of Warren’s novel. According to Ellison, we cannot understand the political problem of the split between the “man of idea” and the “man of fact,” nor the “terrible division of their age” that they are said to represent, without reference to this specifically religious “Moral.”

If Juneteenth is a response to Warren’s All the King’s Men, it is clear that Ellison did not simply answer one particular political vision of the world with another, Warren’s anti-populism with a more refined reform program of his own. Instead he conjured a whole philosophical and even theological vision, one capable of doing justice to his own profound sense that the questions Warren’s novel raised were more properly spiritual, and even more deeply ingrained in American culture, than Warren himself had realized.

It is in the voice of Juneteenth’s primary foil, the larger-than-life father figure who hovers over the whole book—and who so consistently threatened to steal the show that Ellison wrote to Murray of him, in exasperation, “the old guy is so large that I’ve just about given in to him”—that the timbre of Ellison’s response to All the King’s Men, and to the undercurrents it unearthed, can be most clearly distinguished. This mythologically-proportioned figure is Ellison’s Reverend A.Z. Hickman, the adoptive father who takes in the child known as “Bliss” despite the child’s being indirectly responsible for the death of his brother. On his deathbed Sunraider reminisces on a Juneteenth holiday celebrated with Hickman in his youth:

No, the wounded man thought, Oh no! Get back to that; back to a bunch of old-fashioned Negroes celebrating an illusion of emancipation, and getting it mixed up with the Resurrection, minstrel shows and vaudeville routines? . . . Lord, it hurts. In strange towns and cities the jazz musicians were always around him. Jazz. What was jazz and what religion back there? Ah yes, yes, I loved him. Everyone did, deep down. Like a great, kindly, daddy bear along the streets, hand lost in his huge paw. Carrying me on his shoulder so that I could touch the leaves of the trees as we passed. The true father, but black, black.

Juneteenth celebrations commemorate the landing of the Union army in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, and the subsequent reading of the Emancipation Proclamation in the last state in which it had not yet been proclaimed. It is everything Ellison thought America, and especially white America, were not: celebratory, musical, and yet bittersweet, tragicomic, all “mixed up with the Resurrection,” it is an often unashamedly religious celebration of an irreducibly historical event, a loud and proud commemoration of a freedom so fleeting as to seem in hindsight almost an “illusion.” It is also everything Adam Sunraider had attempted to forget.

The politician and apparent “man of fact” in Ellison’s unfinished novel is unmasked by Ellison and revealed to be still also and fundamentally an impotent “man of ideas,” a voyeur in politician’s clothing, a neurotic Nick Carraway dressed up like Jay Gatsby. Contact with reality is concentrated instead in the novel’s original “observed” figure, Daddy Hickman: an adoptive father like Jack Burden’s own but one who—unlike the taciturn Mr. Burden—is not permitted to fade into the background of the book, Hickman is one long, vivid elaboration of the religious themes left implicit in Warren’s novel. Ellison’s Adam, unlike Warren’s Jack, knows in his heart that Hickman is the “true father, but black, black.” Juneteenth longs backward toward a preacher/father who is the opposite of, and perhaps the only antidote to, the dualistic self-delusion of the “white folk mind” which Senator Adam Sunraider so vividly embodies. Adam is really “Bliss,” after all—but only Hickman knows his name.

Juneteenth’s Reverend Hickman is, like Ellison himself, also a great theorist of American dualism. He elaborates on Ellison’s critique of dualistic thinking, complaining to Bliss of the characteristic American tendency to forget that the “The spirit is the flesh . . . just as the flesh is the spirit under the right conditions.” In one of the book’s more striking images, when a reporter asks Hickman why he cries for the shot Adam Sunraider, Hickman thinks to himself that, were he to explain his feelings,

It would be like [the reporter] walking down into a deep valley in the dark and looking up all at once to see two moons arising over opposite hills at one and the same time. Ha! . . . he’d simply shut one eye and swear that one of those hills and one of those moons wasn’t there—even if the one he was trying to ignore was coming streaking toward him like a white-hot cannonball.

All the King’s Men, for all its brilliance, still tends to shut one eye. The novel attempts to simply convert the “man of ideas” into the “man of action”: the assassination of Willie Stark frees up Jack to fall in love with the woman Willie had wooed away from him, and so to finally face up to the realities of the world outside of his research. Jack’s longing for Willie’s charismatic virility and populist appeal is successfully transmuted into the charisma of a childhood romance reclaimed, an old family estate re-inhabited. But this re-inhabiting masks the quiet sacrifice and silencing not just of Willie but also of the religiously inclined father figure, the ex-doctor who gives himself to the poor and solves the problem of evil in his spare time—but who must ultimately be revealed as a false father, and even killed off, in order to clear the way for Jack to find romantic love and embrace his destiny.

Juneteenth offers no such sacrifice, and no such easy answers. With Adam Sunraider, Ellison chose instead to take on the problem of “tragicomic” mankind in all its complexity—black and white, bad and good, preacher’s assistant and United States senator. And with Reverend Hickman, Ellison took head on the daunting task of representing the real—bellowing, backslapping, and “black, black”—voice of the spiritual “father” who calls Adam to make amends with his own history, to recognize himself as “Bliss” and so to remember his own blackness. In doing so, he attempted to give voice to a black American religious sensibility he saw us as increasingly inclined—because “We don’t remember enough,” and this “helps us to continue our belief in progress”—to stifle and silence.

Ellison described Invisible Man as an “attempt to return to the mood of personal moral responsibility for democracy.” That novel’s protagonist observes, when the gathered crowd sings “Many a Thousand Gone” at Tod Clifton’s funeral—mourning a man who has been killed by a white policeman for selling Sambo dolls without a permit—that this singing “touched upon something deeper than protest, or religion; though now images of all the church meetings of my life welled up within me with much suppressed and forgotten anger.”

In Ellison’s work, as in his life, the religious sensibility hangs in the air, incomplete—a half-forgotten memory, resonating obscurely in the notes of old auction-block spirituals. In a speech commemorating his deceased friend and music teacher William L. Dawson, Ellison described himself as “not particularly religious,” but “claimed by music”: “If there were a choir here, I would say let us sing ‘Let us Break Bread Together.’”

Juneteenth’s Reverend Hickman reminds Adam Sunraider of a day he sang, with an enraptured Juneteenth congregation, that same spiritual song. Hickman recalls praying to God, the “Master,” as they sang, and feeling reassured that in spite of—almost, it seems, because of—all the suffering and injustice he protests in his prayer—“police power and big buildings and factories and the courts and the National Guard”—“Still here the Word has found flesh and the complex has been confounded by the simple.” Reflecting on this mysterious reassurance, Hickman says, “It was like a riddle or a joke, but if so, it was the Lord’s joke and I was playing it straight. And maybe that’s what a preacher really is, he’s the Lord’s straight man.”

Ellison’s unfinished masterpiece leaves the reflections of Reverend Hickman, as it eventually leaves itself, like an unanswered prayer hanging over the death of Adam—the wages, ever since Eden, of our sinfulness. That prayer nonetheless suggests the possibility of a deeper frequency even than death, an obscure promise that there must be a perspective in which the “two moons arising over opposite hills” are seen “at one and the same time,” in the kind of tragicomic double vision Ellison spent the forty years between Invisible Man and his own death attempting to describe. As the Invisible Man narrator asked: who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, he speaks for you? Recent evidence suggests that the earth did, in fact, once have two moons. Maybe, as Adam Sunraider urges Reverend Hickman on his deathbed, there is still time to ask: “Tell me what happened while there’s still time.”