One of the memorable and almost lyrical books I read as part of my private instruction prior to entering the Church was the great Jesuit theologian Henri de Lubac’s The Splendor of the Church. The book is a fine example of what I would call “devotional ecclesiology.” It does not—as my own book on the papacy does—concern itself with the more impersonal structures and offices of the Church, but rather with the personal nature of “Ecclesia Mater,” Mother Church, whose maternity is seen vis-à-vis the Mother of God.

That book, and that phrase, came back to mind in reading of the recent announcement by Pope Francis that he is instigating a new feast for Pentecost Monday celebrated in honor of Mary, Mother of the Church. Why this feast? The official decree says that it aims at a “growth of the maternal sense of the Church.”

What, I wonder, does the “maternal sense of the Church” really mean? Here, naturally, my mind turned to post-Freudian psychologist D.W. Winnicott, whose research did so much to advance our understanding of the mother-child dyad and its profound and far-reaching impact on shaping human desires for good or ill.

The British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Winnicott conducted pioneering work on that most primal of relationships, especially during and after the WWII. During this period he worked with children who had lost mothers due to the conflict, or who were separated from their mothers when many children were sent out of London and the larger cities to live in the countryside (or even as far away as Canada) to avoid the tender ministrations of the Luftwaffe.

In studying these and other children and their varying reactions, Winnicott was concerned for both the welfare of the developing child, but also that of the mother, not a few of whom suffered from ongoing guilt over whether they had done enough for their children.

Winnicott’s central insight, published in 1953, was a relief to both: children need, he demonstrated, a “good enough mother.” Mothers do not need to be perfect; in fact, mothers who aim at “perfection” usually end up doing great harm to their children and to themselves. Both mother and child, then, benefit most from a “good enough” relationship—neither too much nor too little. Many mothers (then and today) received this insight with an enormous sigh of relief.

As Winnicott would put it:

The good enough “mother” (not necessarily the infant’s own mother) is one who makes active adaptation to the infant’s needs, an active adaptation that gradually lessens according to the infant’s growing ability to . . . tolerate the results of frustration.The good-enough mother . . . as time proceeds, adapts less and less completely, gradually, according to the infant’s growing ability to deal with her failure.

Elsewhere in this article (“Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena,” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 34) Winnicott spends a considerable amount of time advancing the other key insight for which he is equally famous: that of the “transitional object.” Such objects include a child’s teddy bear or favorite blanket; these play a key role in the child’s developmental understanding of a world of objects beyond itself, a world that he or she can manipulate partially to provide some nascent sense of control.

But mothers are themselves transitional objects as well, and other human beings also play that role. Both good enough mothers, and transitional objects, play the same role in developmental psychology: they assist, says Winnicott, the infant’s growing understanding of how to relate “inner and outer reality” as part of the larger, and ongoing, “task of reality-acceptance.” Transitional objects are key in infancy and childhood, but they remain with us throughout life in different forms, bringing us out of ourselves and our illusions to see and accept a larger reality than we can see or control.

Following Winnicott, I would argue that the Church is, for Catholics, just such a transitional object. Of course, we do not put it in exactly those terms but the opening paragraph of Lumen Gentium does speak in rather homely language of the Church as being “in Christ like a sacrament or as a sign and instrument both of a very closely knit union with God and of the unity of the whole human race” (§1).

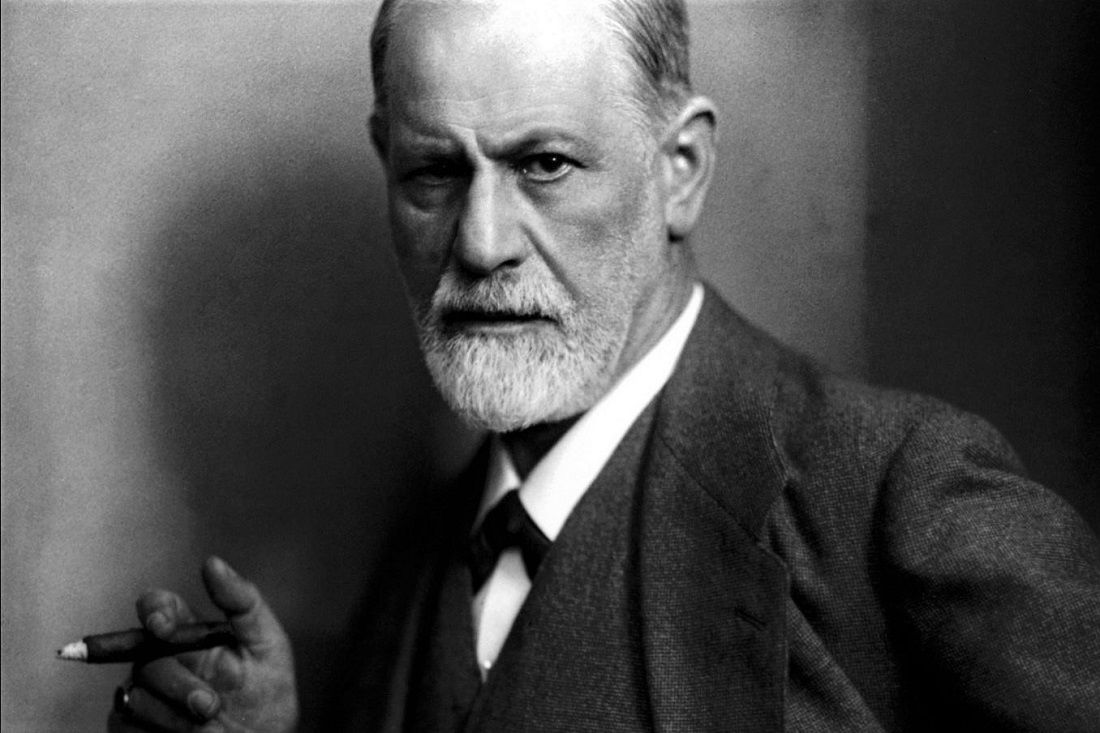

The Church, in other words, is the “object” which calls us out of our solitary illusions of self-sufficiency to recognize other people and the Other who is God. The Church shows us that God is beyond us, our control, and is more and other than whatever illusions (to use Freud’s term in its rightful way) we may have of him. The Church helps us move from solipsistic self-containment and the risks of illusory idols to a life in him who is, says St. Paul, the visible ikon of the invisible God.

The Church does all of this, of course, imperfectly. Precisely to the extent that she is not perfect, but still manages to maintain the faithful in sacramental communion, she is a good enough mother. It becomes highly dangerous when Catholics expect anything more than this from the Church! Those perpetually in hysterics over “scandals” in the Church, or outraged by the latest airborne papal malapropism, or seeing “crises of faith” everywhere, could benefit from a stiff dose of Winnicott’s realism. Of course the Church is only ever going to be a “good enough” mother, not least when all she has for “holy fathers” in Rome and every other diocese are “good enough” bishops. Catholics who have matured psychologically will expect the Church to be nothing more or other than a “good enough” mother as she has always, and only, been. Accept that fact and you can sail serenely through any and every papacy, from the Borgias to Bergoglio and beyond.

But this new feast has a second component: it is that of Mary, who is herself Mother of the Church. What does this Marian dimension bring? Here, we could see Mary not just as a “transitional object” who always points the way to Christ, but also as the “transformational object,” to use the concept of Christopher Bollas, an Anglo-American analyst who has built on Winnicott’s legacy.

“Transformational object” is another term for the lasting impact, the transformational shaping and molding, that objects have upon us even when those original objects have often gradually fallen from view and use as we grow. The impact alone remains, often beyond conscious recognition. The object has transformed us long beyond our conscious recollections of it.

For both Winnicott and Bollas, the mother is herself a transformational object who not only helps the transition from the infant’s self-contained gaze into the wider world, but who also leaves a lasting impression upon us.

Mary, as Mother of the Church, helps to move our self-contained gaze onto Christ, where it belongs in adoration. She remains a living transitional object for us, forever pointing the way and always offering us only one counsel: “Do whatever he tells you!” As one thus transformed by bearing the one to whom she points ceaselessly, she assists our transition out of ourselves and into Christ, who will complete our transformation, allowing us to become partakers of the divine nature itself.

Only in him does the Church move from being “good enough” mother to being the spotless bride of Christ, a process that begins in the Church’s liturgy. This new feast will give Latin Catholics a foretaste of that now, as all feasts do, with the promise of its consummation at the end of the age, when all offices and structures, all sacraments and popes, will cease and the “good enough” Church gives way to the final perfection of the Kingdom.

Featured Image: Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, holding a cigar. Photographed by his son-in-law, Max Halberstadt, c. 1921; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US-Before-1923.