It was the summer of 2014, I entered the Powązki Military Cemetery in Warsaw, Poland, flanked by my closest family members, representatives of the Polish army, and leaders of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance. It was my first time in this cemetery, which I had learned was an historic and venerated place of rest for countless national Polish heroes. It was the unveiling ceremony of the newly placed memorial plaque honoring my grandfather, the late Colonel Edmund Banasikowski. He was a devout Catholic, a hero of the Polish Home Army of World War II, and a resistance fighter who defended Poland against Soviet influence until the collapse of Communism in 1989. Rarely had I felt more pride than in walking towards the stone where his name was inscribed, knowing it would be there for his countrymen to look upon, remember him, and maybe even pray for him for many years to come.

To say he was a rarity among men who fought for Poland, however, would be misleading. Despite the respect towards him I had carried with me since childhood, I knew he was just one of countless partisans in Poland’s history who was hunted, who killed for his fatherland, and who would have died for it. Still today, veterans and fallen soldiers are celebrated in Poland with great laud, especially with unique traditions on All Souls’ Day (called Zaduszki in Poland, literally meaning “for the souls”), when we pray for those in purgatory. I grew up remembering the dead through stories of my family, who taught me to honor the vicissitudes of Polish history. By encountering the history of Poland, we encounter Christ, his sacrifice, and his suffering. As Pope St. John Paul II said, “It is . . . impossible without Christ to understand the history of the Polish nation.”[1] As these resistance fighters fought for freedom, and as Christ suffered for redemption, so do souls in purgatory endeavor for heaven. We, too, can mobilize and fight alongside them, praying for their “celestial paradise”[2], their final freedom.

In a time when war-torn Poland suffered from the strongholds of both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, a young military-trained Edmund Jerzy Banasikowski rose to the rank of an officer in the underground Polish Home Army during World War II. Protecting his country against both aggressors during the war, most notably in the pivotal Wachlarz resistance movement and Operation Ostra Brama defending the city of Vilnius, he fought alongside other war heroes as a quint-lingual spy and a fearless, loyal soldier. He was arrested, interrogated, tortured, and shot in multiple encounters with Nazis and Soviets over the course of the six years of World War II, but survived all battles thanks to Mary, his exalted Queen of Poland. In his widely-published war memoir Na Zew Ziemi Wilenskiej[3], Edmund describes promenading Vilnius—then a part of Poland, now belonging to Lithuania—and arriving at the sanctuary of the Gate of Dawn, Ostra Brama:

As we were headed toward the city centre, the street traffic was nothing out of the ordinary. We reached Bazyliańska Street and from there, just a bound away, at Ostra Brama. Before we knew it, we were kneeling at the feet of the One who had been drawing pilgrims from far and wide since 1706; of the One who—shining at the Gate of Dawn—had been our patroness on these jeopardized eastern rims of Poland.[4]

It would be Our Lady, whose own heart was pierced by a sword, that Edmund would pray for protection from enemies in this turbulent time.

After the war, fearing for his life due to the communist influence that remained in Poland, Edmund fled his country by sailing on a boat across the Baltic Sea to Sweden and later to America, where he lived out the rest of his life. He defended Poland from afar as an anti-communist leader, speaker, radio host, and writer. He met with American presidents such as to advocate for Polish freedom. He arranged a private audience and met with Pope St. John Paul II at the Vatican to discuss sovereignty for their common home. His stories are housed in the archives of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance and in the textbooks of Eastern European history students. My greatest pride, however, is that Edmund Jerzy Banasikowski was my grandfather and that I was blessed enough to be able to listen to his heroic stories and his devotion to Mary personally over the course of countless holidays, weekends, and summers growing up. He was a witness to the strength of faith in a time of war (and peace) and to the virtue of honor to his country and his brothers in arms, many of whom were killed in active duty. He was a national hero, yes, but also a personal hero of mine. Despite the crosses he bore during the war, he never once complained. He never hesitated to drink from the cup that Jesus asked his disciples about in the Gospel of Mark (10:38), and he lived a life of sacrifice by doing so.

As my family took turns giving commemorative speeches about my grandfather’s accomplishments during the event at the Powązki Military Cemetery in 2014, my eyes wandered to the silent graves surrounding my grandfather’s plaque. These graves stood around us upright, as if they themselves were standing at attention to honor my grandfather. I read the names and remembered the stories of these other heroes. Zygmunt Szendzielarz (“Łupaszka”), commander of my grandfather’s Polish Fifth Wilno Brigade of the Home Army, was buried around the corner from where we were standing. Józef Garliński, my aunt’s godfather, was a historian and writer who had been a prisoner of both Auschwitz and the notorious Pawiak prison during World War II as punishment for his activity with the Home Army. His plaque hung just below my grandfather’s. I was surrounded by the unsung protagonists of Polish history, and there were many more whose names I could not see, but whose sacrifice helped Poland to stay free and to remain, as it had been christened in 966, an honorable servant to Christ the King.

The histories of other World War II partisans live on in Polish memory thanks to the efforts of current families, historians, and organizations. Witold Pilecki is perhaps the most discussed of these partisans, considering the ongoing mystery of where his remains lie: after he was brutally murdered by Communists, he is yet to be located and properly buried. During World War II, Witold Pilecki was a member of the Home Army and a critical intelligence agent. He volunteered to be taken prisoner to Auschwitz in order to gather information for Poland’s government-in-exile in London and to organize a resistance movement in the notorious death camp. His story was, in fact, told in the 1975 book Fighting Auschwitz, written by the aforementioned Józef Garliński, a close friend of my grandfather. After his escape from Auschwitz, he fought in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Following the formal end of the war, Pilecki continued to fight for true Polish freedom against Communism and was executed after a show trial in 1948. He stands in history as a quintessential Polish resistance fighter and a devout Catholic, regularly risking his life and suffering brutality and despair for the redemption of others.

Another friend of my grandfather’s, Jan Karski, survived Soviet detention camps and Gestapo arrests and tortures and witnessed the atrocities of war, including mass starvation and transports to death camps, as a courier in the underground resistance movement. He tried earnestly to tell the world of these crimes against humanity, traveling to foreign countries, even meeting with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and other high-profile politicians to rouse interest in their fight for Polish freedom. After much effort and insignificant action taken from the conversations he had with these contacts, he decided to stay in America, becoming a PhD candidate and later a professor at Georgetown University. He spent the rest of his life working, as a Catholic, with Jewish survivors of the war to usher in better understanding of Polish-Jewish relations and helping honor all victims of the war.

Polish World War II partisans were not just intelligence agents and politicians, but also creative artists. Aleksander Wat, a poet, and Józef Czapski, a painter, were both renowned artists whose witness of war has been immortalized in their written words and brushstrokes. Both had encounters with the Soviets: Wat was arrested by the NKVD and housed in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison, while Czapski was part of a mass arrest that resulted in his deportation to Gryazovets, Russia. Czapski narrowly escapes the horrifying fate that 22,000 other Polish prisoners-of-war endured in the 1940 Katyń Massacre; he was one of only 395 people who were not killed. Wat also survived a deportation to Kazakhstan, but he was sent with his family. Both men moved to France following the end of the war, but creatively memorialized their experiences on paper and on canvas, preserved for the world to look upon even today. Wat reminisces his survival of the war, specifically the Warsaw Uprising, and the memory of the dead in his poem ”Towers in Almaty”, which echoes Psalm 137:

If I forget you, fighting Warsaw,

Warsaw, foaming in blood, beautiful in pride for its graves . . .

If I forget you . . .

If I forget you . . .

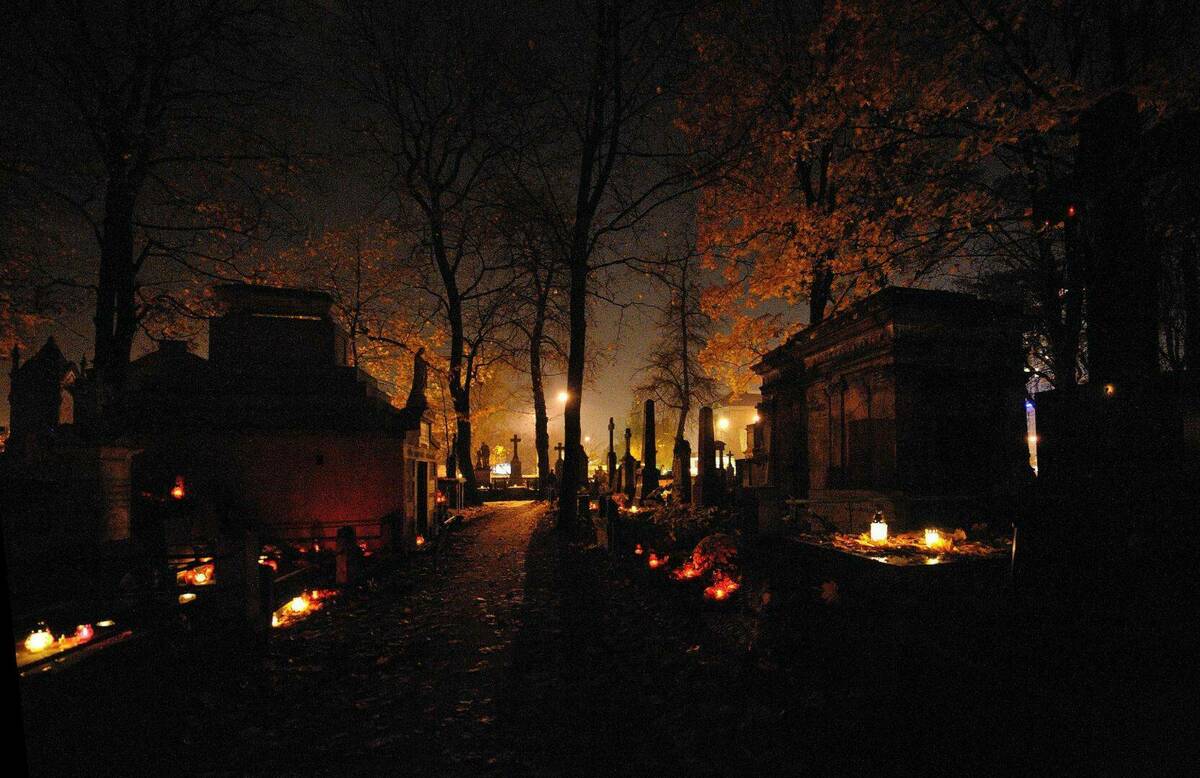

Banasikowski. Szendzielarz. Garliński. Pilecki. Karski. Wat. Czapski. These names, all intertwined in Poland’s brutal twentieth century history, are but a small fragment of the litany of partisans who died, or would have died, protecting Poland. Some are approaching their one-hundredth anniversary of death, yet their names and histories remain vibrant in Polish memory, especially on All Souls’ Day, when millions of people in Poland as well as Polish émigrés gather at the cemeteries where their loved ones and other deceased lie quietly. The sight of cemeteries, radiant in the dark with candlelight from a distance on this holiday, is ethereal. Bouquets of flowers and wreaths overflow the already narrow aisles of dated graves as families gather, walk, and commemorate the deceased. Rosaries are murmured and sometimes the melodies of sorrowful hymns drift over the cemetery.

The Church commends honoring “the memory of the dead and offer[ing] prayers in suffrage for them” (CCC §1032). Indeed, in his historic homily on Victory Square in Warsaw, Pope St. John Paul II upheld the memory of the dead and told his countrymen:

The history of the motherland written through the tomb of an Unknown Soldier! I wish to kneel before this tomb to venerate every seed that falls into the earth and dies and thus bears fruit. It may be the seed of the blood of a soldier shed on the battlefield, or the sacrifice of martyrdom in concentration camps or in prisons.[5]

A survivor of a “personal experience of the ideologies of evil . . . of Nazism and Communism”, “indelibly fixed in [his] memory”[6], he knew the importance of the sacrifices he witnessed during World War II, and he promoted the honor of those sacrifices. This “Son of the land of Poland” was a public example for how his ojczyzna (“fatherland”) remembered the dead. It is an example we can still look to as we anticipate our own death one day.

While the preceding day, All Saints’ Day, is a Holy Day of Obligation and a celebration of the dead who rejoice in the eternal light of heaven, All Souls’ Day is rather a somber holiday, reserved for praying for those in purgatory who are still fighting towards heaven. These souls are contending in purgatory, just as so many Polish patriots battled for their freedom in this life during World War II. Zaduszki is a magnificent petition to honor the forgotten, the discarded, and the embattled, much like the veterans of the very war that defined the country in the twentieth century. While All Saints’ Day is for the Church Triumphant, All Souls’ Day is for the Church Suffering.

The dead rise again, if only momentarily before the general resurrection, in our memory on All Souls’ Day. Candles illuminate their names, their legacies, and their sacrifices. It is an imperative tradition for Poles, and perhaps a recommended one for the rest of the world, not only to honor our partisans, but to uphold the dignity of all the dead. On the front inside cover of his memoir, my grandfather begins his book by quoting the most famous Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz: “Should I forget them, then may You, God in Heaven, forget me.” It is a soldier’s stark petition, and one that holds in itself a great responsibility and requires great accountability and the sacrifice of remembering. Only with the memory of the dead forever with us, in heaven and in purgatory, can we continue to glorify their past life here on earth and hope for their eternal life in heaven. On All Souls’ Day, we pray for them. One day, if our hopes are fulfilled, they may intercede for us.

[1] Wojtyla, Karol. Homily of His Holiness John Paul II. Paragraph 3b. Victory Square, Warsaw, 2 June 1979.

[2] Benedict XII, Benedictus Deus (1336):DS 1000; cf. LG 49.

[3] On the Call to Vilnius. Translated from the original Polish title by this author.

[4] Banasikowski, Edmund. Na Zew Ziemi Wilenskiej. 1990. Editions Spotkania. Translated from the original Polish text by this author.

[5] Wojtyla, paragraph 4.

[6] Pope John Paul II. (2006). Memory and identity: Conversations at the dawn of a millennium, p. 13. Waterville, ME: Walker Large Print.