Christmas Morning, 2017

There is a kind of theology that is not written in words, but written in lives. It is a type of religious reflection, not the reflection on religion of lettered men and women, but the reflection of religion through the performance of active love. If both are indispensable to the Christian tradition, it is also clear that they are neither equivalent nor, perhaps, equally important. It is the latter task: the daily, difficult, and often unremarkable practice of being in the world as a Christian that is the material of Christian life.

Rosemary Therese was that kind of Christian. The oldest daughter of a Polish father and an Irish mother, she grew up in an age when that arrangement was not yet unremarkable nor, amidst cultural and financial pressures, unremarked upon. By certain lights her life was a humble one. As the oldest child, she was not to go to college, but to care for her parents, which she did until the end of their lives. (She once told me she thought she would have studied English.) She married and had seven children of her own. They in turn, signaling further indications of further changes, were given away in marriage to other Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses and one son to the Church. They had children of their own, and now those children have begun to have children themselves. Across her heart, and that of many a homemaker, ran the crossroads of one world, with its local communities, values, and corner bakeries, and its strange successor.

Rosemary lived from 1928 until 2017 – a remarkable 90 years of cultural and religious change. She was born into a world on the cusp of the Great Depression and a Second World War and she died in a world that celebrates wealth and celebrity as the greatest heroism. She entered a world of typewriters, station wagons, and corded phones and left behind one in which her grandchildren carry around tiny computers in their pockets and FaceTime in for Thanksgiving dinner from around the country and the world. Her life of faith began in Latin and ended in the vernacular. Her story is the story of so many men and (especially) women who were born into and came of age in a century and a church coming of age itself with all the pregnant ambiguities and pressing uncertainties of adolescence.

Rosemary knew me longer than I knew her. Yet, it was not until she died that I learned her middle name was Therese. I found this to be a rather profound realization the more I dwelt on it because Rosemary’s life was in its own way “a Little Way.” Amidst complexity, she made her way according to a simplicity that was the simplicity of faith. Not a simple faith, but rather faith’s simplicity which is, as Kierkegaard put so perfectly, “simply to will one thing.” Rosemary, like her near-contemporary, Thérèse of Lisieux, willed one thing. I think in this respect she is worthy of our consideration and, if we dare, perhaps even our imitation. This is especially true for those of us who tend to theorize too quickly in our churches, our academies, and the pages of our journals and, in doing so, run the risk of thinking ourselves out of the simplicity of faith precisely as we think about it.

There is a powerful moment in Thérèse’s Story of a Soul in which she discovers the nature of her vocation with the directness that often accompanies deep insight: “At last I have found my vocation, it is love . . . in the heart of the church, I will be love.” I think Rosemary understood that to love was enough, that it is a vocation big enough to demand all of one’s attention and all of one’s life. The message is simple enough and yet with it Thérèse, a 24-year-old, became one of the great spiritual masters of the modern age and Rosemary, guided by a similar instinct, saw that the choice at every crossroads and the way through each degree of increasing complexity is always the same: to love. To love is to wager on the future. It is often to sow seeds recklessly, not knowing which will take root and where. It is to surrender the consequences of our actions to providence and to the freedom of those we love. Love does not (it cannot) demand reciprocity, yet it creates the possibility for it: that we, having been loved, would respond in love.

The morning of Rosemary’s funeral as we waited to escort the coffin into the church a bishop arrived to concelebrate the funeral liturgy. As he explained later, he considered Rosemary his “spiritual mother.” Not because she was a decorated theologian, but because in his own adolescence she used her station wagon and her time (and a little bit of Polish pushing, no doubt) to drive him back and forth to the local parish in Cranford, NJ with the hope that he might find intimacy with God. It seems to me that those car rides are as eloquent a sermon as any I have heard. Is not this a true model of accompaniment: sharing what we have with one another on the way to meet him? To love is enough. It is not easy, but it is simple. It is we who complicate matters to evade the decision, and in doing so we decide against it.

Both Therese’s were in a way, hidden. Not hidden from the world, but hidden in it: one in the cloister and the other in the home. Yet, life is no less real because it occupies a smaller space. Perhaps it was precisely the smallness of space that allowed each to make her little way so deeply? Both understood that to love is to endure complexity and not to demand its resolution before setting to work. Rosemary welcomed neighbors and in-laws and grandchildren of various faiths and none. She spoke her mind, always. She interceded, always. Amidst the increasing uncertainty of an increasingly untethered age, there was a fierceness to her devotion that we would do well to consider. There were not two churches for her—the one with the pews and the field hospital in the streets. She was a daily communicant who participated in lay movements and bible studies and also took her family to march for civil rights in Jersey City. She sang the Salve Regina, On Eagle’s Wings, and We Shall Overcome with equal volume. To love Christ, after all, is to love all of him, is it not? Whether we find him hidden in bread and wine or in the distressing disguise of the poor or in the plight of the exile. To love Christ is to share him, in parish life, in small faith communities, and where there is injustice. To love Christ is not to prioritize, but to love all equally because all are equally beloved. Such an integrated vision of the life of faith demands of us not, in the first place, wisdom or even sanctity, but love as the route to both.

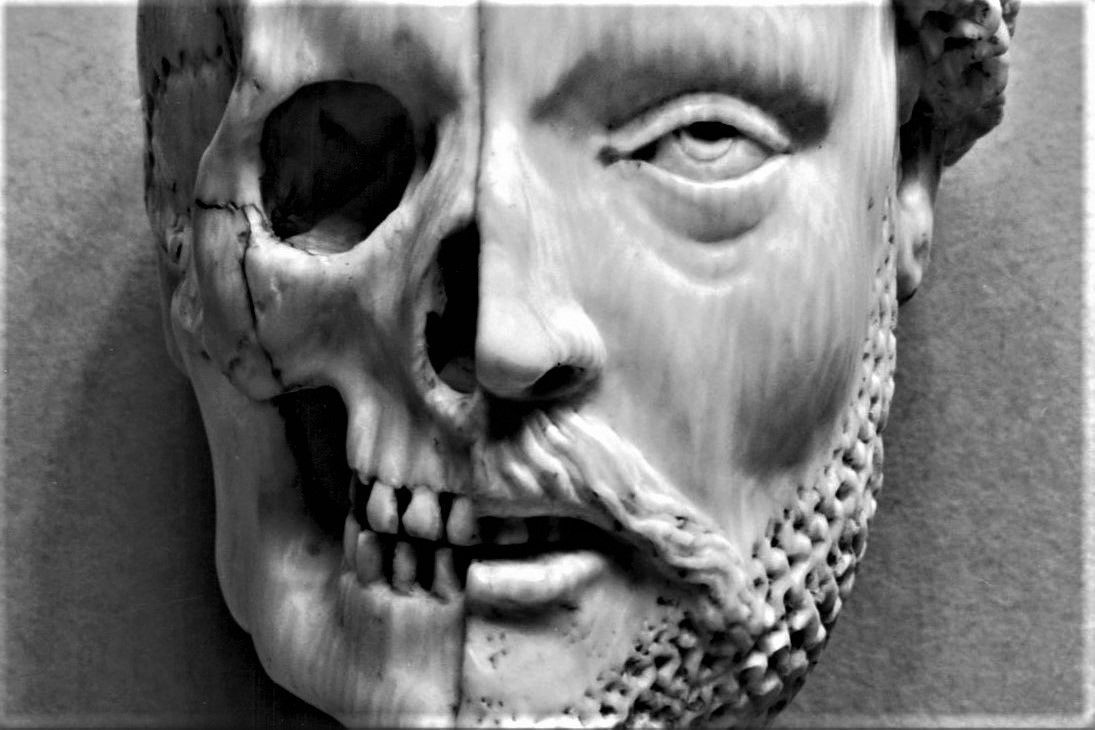

Rosemary was my grandmother. And I had the opportunity to say goodbye to her knowing it would be my last goodbye. That is a very fortunate thing, but also a very strange one. She was sedated; breathing, but only faintly, and looking half herself. The body that had served her well in serving others had at last betrayed her as all our bodies do. What does one say in such a situation? Many things and none. The impossibleness of such a moment is matched only by its sacredness. In the adjoining room, my grandfather (her partner in all things sacred) turned up the TV volume in an intuitive gesture of protection and of reverence. Those final moments were impossible because death is impossible. We cannot grab a hold of it, but are grabbed by it and forced to contemplate its terrible size and arrogant permanency. Faced with it we cannot mean enough, nor mean deeply enough with our words. My sisters and I said many things to her. We thanked her and held her hands and prayed at her side. But the moment was too full and we were too small. The ritual recitation of the prayers she loved was a salve, a kind of spiritual reflex when faced with the silence. But what are a Hail Mary and an Our Father in the end, but reverently inadequate attempts to draw the shape of a mystery? The least inadequate ways to cope with the interior dimensions of both a sadness and a hope whose yearnings are infinite. Death clarifies what we love, this we have known since Socrates.

In the midst of increasingly intense and competing narratives within the church and without—but especially within it—Rosemary, my Gram, reminds us that the Little Way is always possible. We can always choose to love. The simplicity of such a decision should not prevent us from grasping either its difficulty or its profundity. It is love that clarifies our thinking, not more thinking. It is love alone that can dissolve that inveterate bias native to our nature. Love is always the encounter of a person, preeminently Jesus of Nazareth, as Benedict XVI and Francis never cease to remind us, but through him it is also the desire for encounter with everyone else. Love alone rents asunder our petty and self-serving horizons and holds out to us the beautiful possibility of loving God with God’s own love. A love wherein we become capable of earnestly desiring the good of our neighbors and capable of the sacrifices it would demand.

Rosemary was a model of that kind of love and so she is a model for all of us living in the meanwhile, the time between confusion and clarity, between injury and healing, between the earnest desire for peace and its accomplishment. Her life invites us, has invited me, to consider how to live amidst the coming-of-age that is the story of our own lives no less than those of our grandparents. Caught between serious questions and their answers, between the Gospel and a secular age that further unlocks its inner riches, between faithfulness and selfishness; such a predicament demands that we earnestly and honestly seek clarity, but it also demands that we often live before it is reached. Is not the testimony of our sacred texts that we must gradually become certain kinds of people through sacrifice before we can “see” and “hear” and “understand” the fullest answers to our deepest questions? At least then, as we drive back and forth making our Little Way, let us not forget to love in the meanwhile.