One of the best expressions of “Catholic community” in Higher Education is the academic colloquium. Only recently, Pope Francis reminded a gathering of Italian teachers that a commitment to free association was a way of fostering “an open outlook towards the social and cultural horizon.”[1] Such opportunities for shared exploration of ideas are welcome reminders of the Church’s longstanding engagement with the cultural challenges encountered in the mission to evangelize. It could be argued that such events risk presenting an elitist face to both the world and the wider Church. At their best, however, they offer multiple opportunities for fruitful dialogue on how to address the challenges of relativism and materialism, which, according to Pope Benedict XVI, make up a contemporary “educational emergency.”[2]

I had the privilege of recently organising one such colloquium at the University of Glasgow (founded in 1451 by Pope Nicholas V). Catholicism, Culture, Education (the title of the Colloquium) was an opportunity for an international audience of Catholic educators (mainly in third-level institutions) to share thoughts on how to energise their mission. This was the annual colloquium of the Association of Catholic Schools and Institutes of Education (ACISE), a sectorial body of the International Federation of Catholic Universities (FIUC).

The process of planning such an important gathering offered me the space to consider the essential features of any colloquium on Catholic education. At the opening session, I suggested to the assembled academics that my aim was to give them an experience of good liturgy, fine hospitality and, of course, academic papers of high quality. While there was an element of humour in the comments, it quickly became clear that those elements could, in effect, become foundational pillars for Catholic academic life. I will reflect now on the importance of liturgy in Catholic academic life.

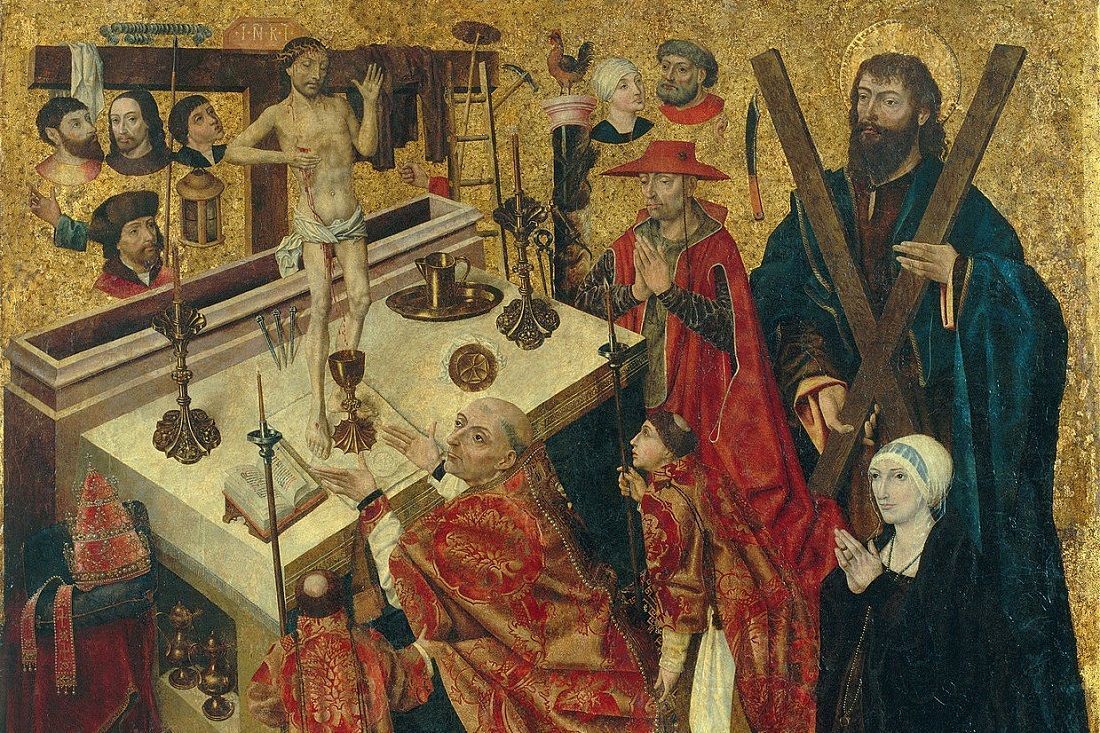

Liturgy is neither an addendum to Catholic life nor something constructed according to particular whims of clergy and congregations. Rather, liturgy is where the human person encounters the living God who is seeking his people in love; the sacramental cosmos illumines our dimmed eyes. This reminds me of an essay question from my Masters study: “Liturgy is God’s search for us, not our search for God. Discuss.”

While we should think carefully before taking sides in the fraught “liturgical wars” often played out on the battlefields of the web, that does not grant us a license for indifference. In that vein, it is hard to remove from my mind those stark poignant words found in Shakespeare’s Sonnet LXXIII:

Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

Without engaging in a wider critical and contextualised exegesis of these famous lines, do we not read therein a haunting description of much of contemporary Church life? How can we ignore increasingly empty churches, a fading of the cultural fabric of Catholic life and, to be sure, the arrival of liturgical music that owes more to musicals than to the great traditions we inherited. This is not to say that developments in doctrine and practice cannot take place, far from it; yet if any reform of liturgy to is be authentic, it must be seeded, as Blessed John Henry Newman reminded us in An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, in what has come before.[3]

So why is liturgy an important aspect of Catholic academic life? Liturgical celebrations in academic gatherings are, crucially, reminders of the need for humility. Academic life can leave us prey to vanity: our shared vocabulary is awash with terms like “esteem,” “honors,” “prizes”; such a lexically loaded vocabulary does not sit well with, and could indeed work against, the obligation to serve the Church and wider community with our intellectual endeavors. The liturgy, where we freely receive sacramental grace, is a necessary corrective to the many temptations to vanity that lie like landmines in the territory we inhabit.

In his powerful short story, Master Halcrow, Priest, the Orcadian convert to Catholicism, George Mackay Brown, describes poignantly the reaction of a faithful Catholic priest to the efforts of Scottish Protestant reformers to remove him from his beloved church:

Thereupon I bowed my knee to the altar where lay the Body of Our Lord and turned my back on those men and left the kirk.[4]

In leaving his cherished place of worship, Master Halcrow creates what will become another “bare ruined choir,” yet the importance of the sentence lies in the humble act of genuflection towards the Real Presence. We can learn from this. The proud bow only to their own profile but Catholics are called to look beyond our limited horizons.

Reflection on liturgy must flow beyond the planning of an academic colloquium to the ordinary life of the parish. It is the local Church community that is called to be a centre of “Catholic culture,” not just the Catholic academic centre. In that vein, I conclude with two practical parish-oriented considerations with regard to the liturgy.

Vigil Masses. Has the introduction of Sunday Vigil Mass somehow diminished the impact of Sunday? Is it the case that Mass on a Saturday evening / late afternoon is more of an add-on to Saturday’s activities rather than a vibrant anticipation of the Day of Resurrection? Pope John Paul’s Apostolic Letter, Dies Domini (1998) has something important to say:

Sunday is a true school, an enduring programme of Church pedagogy — an irreplaceable pedagogy, especially with social conditions now marked more and more by a fragmentation and cultural pluralism which constantly test the faithfulness of individual Christians to the practical demands of their faith.[5]

A restructuring of the parish “weekend” timetable—while bearing in mind that “weekend” is a problematic phrase as Sunday is the first day of the week, not a component part of a two-day denouement to the week’s activities—could be an important step in strengthening our Catholic culture.

Daily Mass. If the Mass is truly the font of Catholic culture, we should be eager to encourage more and more people to attend Mass daily. This requires a shift in attitude towards what are often unchanged ways of doing things: how often do we see daily Mass celebrated at a time that would not suit those with standard working patterns?! While bearing in mind the question of availability of clergy, we need to ensure that our parishes offer a flexible schedule of daily Mass times. This will, of course, mean a good degree of inter-parish co-operation to bring about a harmonious pattern of worship. What pastoral benefits could flow from such an ambitious move!

To conclude, the promotion of Catholic culture must be rooted in love of the Mass. Whether it be in academic colloquia or in the organisation of parish life, it is the Mass that lies at the heart of what we do.

[1] Pope Francis, Address to Italian Catholic Primary School Teachers, January 5 2018: https://zenit.org/articles/popes-address-to-italian-catholic-primary-school-teachers-association-aimc/

[2] Pope Benedict XVI, To the Faithful of the Diocese and City of Rome on the Urgent Task of Educating Young People, 2008: https://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/letters/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_let_20080121_educazione.html

[3] John H. Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, (1878: 2003)

[4] George Mackay Brown, Master Halcrow, Priest. A Calendar of Love and Other Stories. London: Flamingo, 1996.

[5] Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Letter, Dies Domini, 1998, 85: https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1998/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_05071998_dies-domini.html