In a recent blog post, Fr. Michael White (author of Rebuilt: Awakening the Faithful, Reaching the Lost, and Making Church Matter) argues that young children and toddlers are unable to understand the Eucharistic liturgy, and therefore a parish ought to offer a “special” worship experience for them that is age appropriate. Lacking the capacity to participate in the act of Eucharistic worship, they create a disruption that disturbs the ability of the parent to “devote their full attention to worship.”

Reactions to Fr. White’s argument via social media have been full-throated. Fr. White heaps much of this scorn on himself, complaining that he is unable to concentrate on preaching when there is a crying baby in the front row. He mocks parents who attend the liturgy with their children in the front row of the Church—as if young children can really see what is going on. The blog entry is the kind of thing that any prudent editor or communications director would have refused to publish since it demonstrates an intolerance to children that is, well, not that attractive for a parish interested in evangelizing adults.

From my perspective, Fr. White’s argument is flawed not simply because he argues for the exclusion of young children from the act of parochial worship. Rather, the blog post reveals a misunderstanding of the nature of the liturgical act itself. This misunderstanding is not unique to Fr. White, but has infected most Catholic parishes in the West well before Vatican II. When one reduces the liturgical act to “understanding,” then there is an erasure of the contemplative, aesthetic, and thus embodied formation that is integral to a worshipful existence.

It is no accident that Fr. White highlights “hearing” above “seeing” in the Eucharistic liturgy. He compares the Mass to a lecture where one must devote one’s attention to complicated arguments in order to participate fruitfully in the lecture. Since children cannot follow these complicated arguments, we do not bring them to these lectures (Fr. White has probably never attended the McGrath Institute’s Saturdays with the Saints where there are children aplenty). Of course, the Mass is not akin to an academic lecture. If participation in the Eucharistic liturgy requires the same degree of intellectual capacity as a scholarly lecture, then the fruits of the Eucharistic life are reserved only for those with the appropriate intellectual understanding. That would exclude many with physical or intellectual disabilities, as well as anyone unable to speak or understand the particular language in which Mass is offered.

Indeed, this assumption is not unique to Fr. White. Most liturgical catechesis has emphasized the need for “understanding” what we do in the liturgy for the liturgical act to be fruitful. This understanding has tended to function cognitively. Namely, the Christian must learn the meaning of the signs and symbols used in divine worship, the structure of liturgical prayers and the lectionary, the Church’s theology of the liturgy, and more. If only men and women could “understand” what is taking place in the act of worship, then they would throw their whole self into the liturgical act. Understanding would lead to a meaningful experience.

Often, this emphasis on understanding was presumed to unfold simply through an encounter with the liturgy. Here, Fr. White is not wrong to argue against a facile liturgical formation that functions simply through familiarity with the Mass. Catholics often presume that going to Mass will communicate everything to the child or adult needed for a robust Christian life. This assumption presumes that liturgy communicates theology or the experience of faith through complex liturgical signs, and the only thing required for liturgical participation is recognition of the “meaning” of these signs. Whether the liturgy is beautiful or not does not really matter.

The primary pedagogy of the liturgy, in this instance, is still related to hearing. One must be “told” the meaning of the Eucharist. One must “hear” about the relationship between baptism and the Red Sea. Aesthetic perception in this approach ignores the rest of the human senses, the possibility that liturgical meaning is not a matter of being told something but entering into these signs, and then slowly discovering the splendor of divine love available in the act of worshipping the Eucharistic Lord. Liturgical formation is less a matter of “being told” things, understanding them, and is instead concerned with a contemplative and embodied aesthetic beholding.

Fr. White’s argument for the exclusion of children puts the act of hearing upon a pedestal above all the other senses. And in this, he eliminates the contemplative and aesthetic dimensions of liturgical formation. One can see problems with this elimination both theologically and psychologically. It is in essence the root of an American Catholicism that risks eliminating everything but the “message.”

The mystery of Christianity, the enfleshment of the Word, begins for the human person with an act of beholding. As Hans urs von Balthasar writes relative to the Incarnation in his first volume of The Glory of the Lord: Seeing the Form:

The emphasis is given to a certain seeing, looking, or “beholding,” and not to any “hearing” or “believing.” “Hearing” is present only implicitly in the reference to the “Word” become man, just as “believing” is implied in that what is seen is the mystery that points to the invisible God. But the all-encompassing act that contains within itself the hearing and the believing is a perception . . . in the strong sense of a “taking to oneself” . . . of something true . . which is offering itself (The Glory of the Lord: Seeing the Form, 120).

In every act of seeing, touching, hearing, tasting, and feeling, the liturgical actor for Balthasar is engaged first and foremost in an act of perception. The Christian is beholding the mystery of divine love become flesh, a gift that is first to be received before it is to be understood. Although the human being is made to perceive this gift of love, it is never entirely comprehensible to anyone insofar as it is the doxa (glory) of God made manifest through the flesh. If one imagines that one can grasp the mystery of divine love fully, then one is no longer worshiping God but oneself. The task of Christian formation, for Balthasar, is to make space for the movement from beholding to an understanding in which the Christian offers his or her whole life as a return gift of love. He writes:

Man is not merely addressed in a total mystery, as if he were compelled to accept obediently in blind and naked faith something hidden from him, but that something is “offered” to man by God, indeed offered in such a way that man can see it, understand it, make it his own, and live from it in keeping with his human nature (The Glory of the Lord: Seeing the Form, 121).

In divine revelation, our natural senses are overwhelmed with the totality of divine love, akin to the way that we are overwhelmed in hearing Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. In both instances, the task is not a matter of intellectual capacity but the formation of senses that can perceive the wondrous radiance made available through the concrete form. It is an attuning of the human person to adore the living God.

Further, perhaps this beholding, this immersion into the liturgical act in all of its embodied sensuousness does introduce the young child into this mystery of divine love. In his recent study, The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding, Mark Johnson argues that infants are involved in processes of meaning-making not through the production of meaningful signs of speech but through embodied movement:

Babies and children have to learn the meaning of objects and events that will eventually make up their mature, shared experience of a common world. They must learn to understand what is happening to them—what they are experiencing and what they are doing. What is given to infants are their various sensorimotor and conceptual capacities (which must themselves be activated through experience and continually developed, often in certain ordered sequences and within certain time frames) that set constraints on what can be experienced and how it can be meaningful to humans. These mental capacities are extremely plastic and dynamic, and the way they develop depends partly on genetic programs and partly on the specific experiences and developmental history of the individual infant. We thus grow into a meaningful world by learning how to “take the measure” of our ongoing, flowing, continuous experience. We grow into the ability to experience meaning, and we grow into shared, interpersonal meanings and experiences (35).

The baby is never told that the human face is an important part of the body but instead discovers this fact through perceiving the face of the parent who almost instinctually lowers himself or herself face-to-face with the babe. The child comes to recognize certain features of the face not through propositional knowledge but through an embodied perception of this particular face. Likewise, the child begins to imitate the facial reactions of the parent. No one ever tells a six month old how to laugh, how to move the muscles of the face to make a smile. They are not exhorted to do so through the abstract movement of the will. The desire to smile is discovered through the embodied act of perception. The young child learns to smile in return, discovering in this interchange the very basis of human communication and trust.

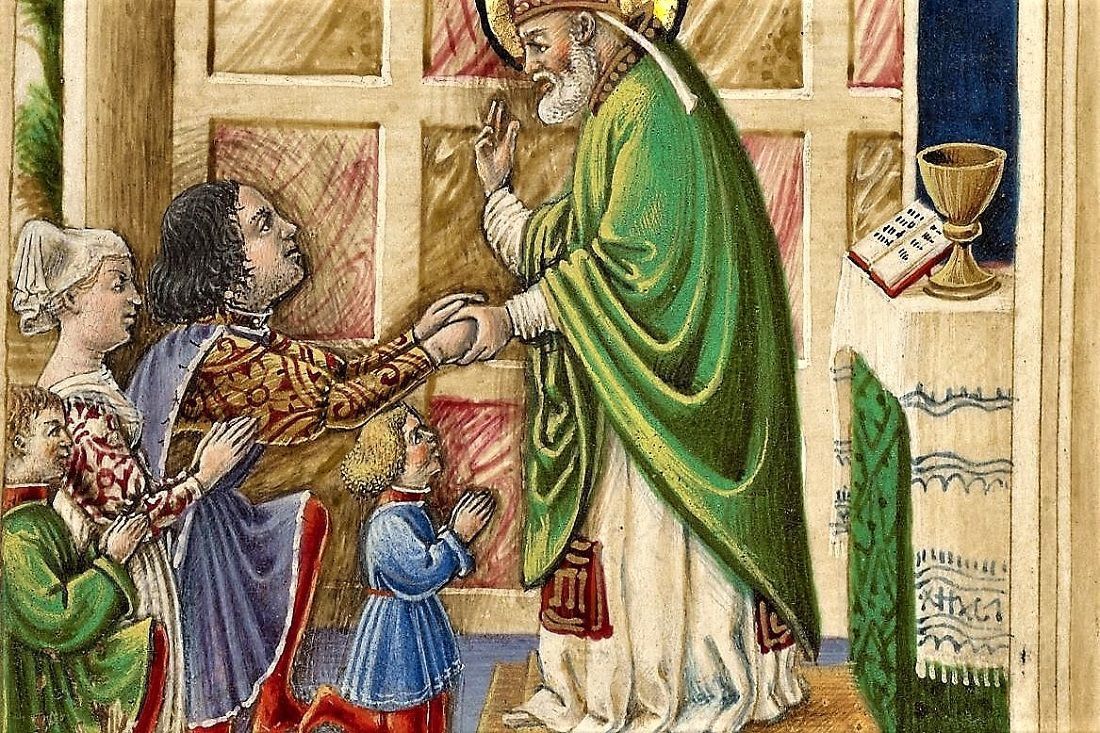

Thus, Fr. White is wrong both theologically and psychologically. The young child is looking at the altar because the young child is always looking, perceiving, and imitating. No, the young child is not able to comprehend the sermon that is given or the particular meaning of the opening collect or why there is a pelican or Lamb on the altar. But the young child is discovering in the act of Eucharistic worship according to his or her capacity that this act really matters. The child perceives the facial features of adults, who are ideally engaged in contemplative wonder at the Eucharistic mystery. They hear the reverberant notes of the organ and they see and smell incense. They are learning the very meaning of what it means to be a liturgical creature even as they sleep in their mother’s or father’s arms during the Eucharistic liturgy.

Young children perceive the mystery of divine love in the mode that is appropriate to an infant or young child. To deny them this act of perception is in essence to say that God can only communicate in the mode that we find appropriate for our sophisticated, intelligent, rational, and adult faith. It is to eliminate the human body itself from the act of worship, since the primary activity is the communication of a message.

In this sense, Fr. White’s blog post is but endemic of Catholic worship in the United States at this stage. Liturgies are cacophonies of verbal proclamations, of sermons, of explaining rites and the meaning of feasts. There is so little to behold in churches that have been built as suburban shopping malls. Music is chosen not because it provides something to perceive, the beauty of ordered sound used to worship God, but instead to get across a “message” in hymn texts that are often more ideological than aesthetic or theological. There is often so little gravitas to the activity of worship, a sense that we have to adjust ourselves to adore God, since what we long for is a pleasing and meaningful act of worship.

Perhaps, what we need to do is not exclude children from the act of worship. Instead, we must understand liturgical worship as if the primary participants in the act of worship will be infants. Instead of relying on endless speech, on communication media including video screens, we must create spaces where all the senses are involved in worship. Emphasizing understanding through speech brackets out a good deal of what it means to be a human being.

So rather than create a special liturgy for children appropriate to their understanding, let us have music that is worth listening to and singing along with. Let us build altarpieces and reredos that actually give both infants and adults something to behold in worship. Let us attend to the way that light sanctifies space, how color delights the eye. And perhaps some of the children are bored at Mass, not because they are incapable of understanding what is going on, but because there is too much speech and not enough silence, not enough embodied action, not enough to behold.

My toddler daughter does get bored at Mass. And my act of worship is not to whisk her away to some room where she can encounter God without me. Instead, it is to perform an act of worship where I slowly take her around the church, showing her images that delight the eye. I sing along to the Mass, inculcating her into the words of praise that are integral to our worshipful life. I mark her body with the sign of the cross as the Gospel is proclaimed. She is learning a worshipful mode of existence not through speech, not through some alternative liturgy appropriate to her toddlerhood. And as she learns, so do I. I learn once more to delight in genuflecting, in chanting, in singing, in beholding.

In the end, the Church’s liturgy was made for infants. It is us—in our boredom and apathy—who have to change, rather than the children.