In his short and widely read text, The Burnout Society, the contemporary Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that the society we live in is distinguished by the prevalence of psychological disorders such as depression, ADHD, anxiety, and, more recently, burnout. Indeed, he proposes that we live in a burnout society and that these disorders have their root in “overproduction, overachievement, and overcommunication.”[1] Ours is no longer a disciplinary society where being overworked is experienced as an external imposition as it was for the worker of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. We have transitioned into what Han calls an achievement society, and with this transition has emerged the new human ideal of the entrepreneur. Burnout is, then, a pathology specific to an achievement society and the entrepreneurial subject.

Like many critiques of this kind, it operates in a quasi-prophetic register. Han’s analysis therefore tends toward a high level of abstraction that inevitably creates blind-spots. Nonetheless, it is hard to deny that he is giving expression to something important about our current historical-cultural moment—namely, a growing sense that our relation to work is becoming destructive. Ethical issues pertaining to just wages, work conditions and hours, wealth disparities, job insecurity, and so forth are of course central here. But something else is at play, something that requires a more fundamental form of analysis regarding what we may call the meaning of work in relation to the meaning of the human. Is “work” our highest good or is it a lower good that ought only to serve higher goods? Put otherwise, do we find our distinctively human mode of flourishing in activities higher than work, however this higher may be understood?

Drawing from Hannah Arendt’s suggestion in The Human Condition that “man may be . . . on the point of developing into that animal species from which, since Darwin, he imagines he has come,” Han proposes that an achievement society increasingly robs us of that which renders us distinctively human.[2] For Arendt, the modern self is increasingly more “animal” because of its lack of individuality and the decrease of what she calls (political) action. For Han, this framing of the situation is no longer applicable. The entrepreneur is distinguished by an excess of individuality and activity, not a lack. We must market ourselves within a competitive job market that demands overachievement. Han proposes that what is being lost in the achievement society is not individuality or action but more so the distinctively human capacity for contemplation—that is, of attending to “the way things are, which has nothing to do with practicality.”[3] Contemplation escapes the “achievement-principle entirely.”[4] Exposed to an excess of stimuli and information, what is prized in the entrepreneur is a kind of hyperactive and multi-tasking mode of attention that is in fact animal-like: “Multitasking is commonplace among wild animals. It is an attentive technique indispensable for survival in the wilderness. . . . The animal cannot immerse itself contemplatively in what it is facing because it must also process background events.”[5] Indeed, the entrepreneurial ideal is nothing but “an animal laborans that exploits itself—and it does so voluntarily, without external constraints.”[6]

By orienting his analysis around an account of distinctively human capacities, Han moves beyond the political, economic, and ethical toward a form of analysis that—for lack of a better phrase—I will here call philosophical anthropology. It is a mode of analysis that has an ancient and venerable pedigree. For Aristotle and Plato, humans find their species-specific flourishing in those activities that are distinctively human (i.e., political action and contemplation, with the latter usually “ranked” as higher than the former). Indeed, it was the tendency of the ancient Greeks to see certain forms of (bodily) labor as inferior activities that bring the laborer closer to an animal mode of existence. Although many medieval thinkers saw labor as a good that is proper to human nature, the denigration of bodily labor in relation to the more distinctively human activities of political action and contemplation continued into the middle ages. Philosophical anthropology is, moreover, central to Marx’s critique of capitalism. Capitalism alienates the worker from what is distinctively human, namely, labor. It thereby renders the worker more animal-like.[7] As indicated above, Arendt’s The Human Condition is a work in philosophical anthropology, according to which the modern self is increasingly approximating an animal mode of existence.

Although his argument at many points resonates with Marxist critiques, Han ultimately argues in favor of the contemplative ideal that Marx tends to denigrate. He therefore adheres to a non-Marxist philosophical anthropology. Contra Marx, we are not homo laborans. To make labor (or “work”) the highest of human activities is ultimately to treat the human as just another animal. Han also distances himself from Arendt for whom the highest human activity is political action. In this sense, Han shows himself to be pre-modern in disposition. The activity that is distinctively—and hence normatively—human is contemplation, framed as a giving up entirely on the achievement-principle. Work may be a necessity, but it does not constitute our distinctively human mode of flourishing. What we need today more than ever is less work, less achievement, and, correlatively, less entrepreneurial individualism.

What I am proposing here is that Han’s text can be read as an exercise in philosophical anthropology. Our achievement society is one that has, so to speak, made a decision in favor of homo laborans—or what we may also call homo faber or homo economicus—as its philosophical anthropology.[8] It serves as the achievement society’s ideological foundation. Accordingly, we see ourselves as born for work and as finding our ultimate fulfilment in it. Work becomes a quasi-religious vocation that demands from us our total commitment, even if it is to the detriment of goods such as friendship, family, health, and virtue. A thorough critique of the achievement society therefore requires bringing this underlying philosophical anthropology to light and questioning it.

In our current post-modern moment where strong claims about “the” human and human distinctiveness in relation to other animals tend to be treated with suspicion, Han’s analysis feels simultaneously timely and out of place. It is a curious argument at times, one that I will question further below. Before doing so, however, I first want to complement it by turning to a once widely read text—namely, Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948). There is no indication that Han is aware of Pieper’s text, but, like Han, he critiques homo laborans and does so at the level of philosophical anthropology. Like Han, Pieper argues in favor of the contemplative ideal. In this sense, Pieper’s Leisure—although outdated in certain respects—reads as an exemplary precursor to Han’s philosophical anthropology.

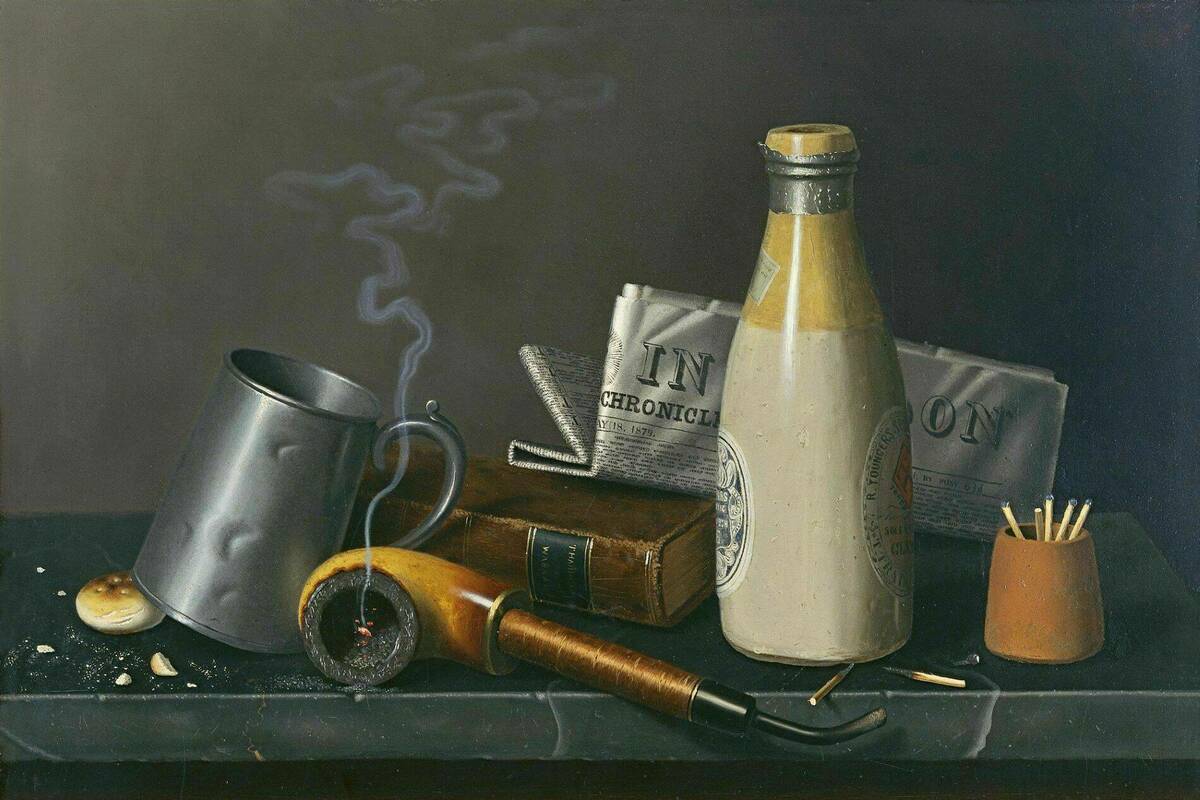

Pieper takes it for granted that we in the Western nations have transitioned into a new era when it comes to the meaning of the human. We are in the “age of work” in which the “worker” is the new ideal human. By “work” Pieper understands something very broad—namely, any activity that is oriented toward production and changing the world. What defines the worker ideal is an ever-present readiness to work and, indeed, a readiness to struggle and suffer for the sake of work. The worker glorifies effort and tends to mistrust anything that does not involve effort and that does not exhibit any tangible utility. Although he does not put it in this exact manner, the age of work is for Pieper the age of homo laborans.

Pieper does not denigrate work in itself. It is a necessary aspect of the human condition and is therefore good. What he calls the “work-world” is, then, an integral aspect of the human world. This notion of the work-world is central for Pieper’s analysis, and so I will say a few things about it. Pieper develops a kind of social-phenomenological description of this work-world. As distinct from other “regions” of the human world (e.g., religious, aesthetic, domestic, and so forth), the work-world is constituted by specific ends, a certain logic, and characteristic moods. In it we seek to satisfy our immediate and necessary needs (i.e., money for food, rent, and so forth). Its logic is utilitarian and the reasoning that dominates it is instrumental reason: “[the work-world is] the world of usefulness, of purposeful action, of accomplishment, of the exercising of functions; it is the world of supply and demand, the world of hunger and the satisfaction of hunger.”[9] As workers, it is imperative that we attain the skills and habitus that will allow us to succeed in the work-world as it is. Questioning the work-world is a luxury most cannot afford. As for its characteristic moods, the work-world is marked by tensions, burdens, and anxieties, stemming not just from the necessity of meeting deadlines but also from the ever-present threat of unemployment and—in most of our cases—of simply making ends meet.

Admittedly, the above description of the work-world reads as disparaging. But to repeat an earlier point, Pieper claims not to be denigrating work and the work-world per se. The work-world is a necessary region of the human world. Nonetheless, it is precisely this work-world and our activity in it that Pieper characterizes as closer to the animal. The argument is not always easy to follow. It also builds upon a particular construal of the animal that is quite foreign to Anglophone readers. Here Pieper turns to the biologist and early ethologist, Jakob von Uexküll.[10] Arguing against mechanistic philosophies of nature in the early twentieth century, Uexküll emphasized the subjective dimensions of organic life and the ways in which organisms dwell within meaningful perceptual worlds that can be utterly foreign in comparison to our own. Animals construct their environments (or perceptual fields) insofar as what lights up as meaningful (or relevant) for them is a function of their sensorimotor repertoire, moods, skills, and so forth. This subject-centered, constructed, and meaningful perceptual world is what Uexküll calls the animal Umwelt (“surrounding-world”). It is to be sharply distinguished from the Umgebung, where the latter is something like the world surrounding an animal as independent of it and as we perceive it.

According to Pieper’s reading of Uexküll, the animal Umwelt is “a selective reality, determined and bounded by the biological life-purpose of the individual or the species.”[11] Elsewhere he describes it as a “selective milieu . . . to which the animal is completely suited, but in which the animal is also enclosed.”[12] The animal cannot stand back, so to speak, and realize that it is enclosed and bound to a limited reality. In this sense, to be an animal means to be totally bound to, or enclosed in, the limited reality of an Umwelt.

While Pieper never quite makes it explicit, his framing of the animal Umwelt is clearly aimed at drawing a connection between it and the human work-world. Much like the animal Umwelt, the human work-world is a “selective world determined solely by life's immediate needs.”[13] As noted earlier, we must habituate ourselves to the work-world and make do with the opportunities at hand. We have very little option but to accept the “usual meanings” and “accustomed evaluations of things” in the work-world.[14] In this sense, we operate within the quasi-animal work-world by means of an instrumental mode of reasoning that we share in common with other animals.

Work is necessary and a good that corresponds to one aspect of human nature, but the age of work exhibits a tendency that Pieper deems its principal threat—namely, what he calls the totalizing tendency of the work-world. This is one of the text’s most important insights. The effect of this totalizing is that we become increasingly bound to, or enclosed in, the work-world: “To be bound to the working process is to be bound to the whole process of usefulness, and moreover, to be bound in such a way that the whole life of the working human being is consumed.”[15] It is to give oneself over entirely to the work-world, to have one’s dispositions, reasoning, desires, and so forth almost entirely molded by it. It means losing sight of the fact that the work-world—with its ends, utilitarian logic, and governing moods—is only a partial reality and that the habitus required for the work-world ought only to have a limited reach. In brief, being bound to the work-world represents an animal-like “narrowing of existence.”

This being bound to the totalizing work-world is demanded within the age of work. For our society to carry on running as it is, it is crucial that work is not seen as a necessity that we put aside once certain basic needs are met. It must become something more like a vocation so that we willingly become a mere “functionary” in the work-world (or “auto-exploitative” as Han puts it). According to Pieper’s framing of the situation, all of this ultimately represents an “animalizing” of the human world. As the work-world extends its totalizing reach and as we become increasingly enclosed in (or bound to) it, we lose the ability to step back and see the work-world for what it is, namely, a limited sector of reality as a whole. The animal-like work-world becomes the world as such.

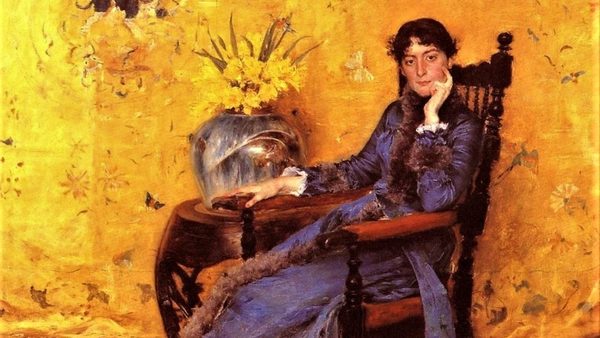

The result of this is a gradual loss of the distinctively human capacity for leisure. By leisure, Pieper does not mean a “break” from work that ultimately only serves to prepare us again for work (e.g., binge watching a TV series or a vacation). This kind of leisure has already been co-opted by the work-world. Leisure properly understood is a specific condition or formation of the soul. It places its possessor in conflict with the “worker” ideal and resists the totalizing tendency of the work-world as a force that shapes the soul. Three characteristics mark the leisured soul. First, leisure is “an inner absence of preoccupation, a calm, an ability to let things go, to be quiet; . . . [It is] the disposition of receptive understanding, of contemplative beholding, and immersion in the real.”[16] Leisure disposes one toward a receptive-contemplative relation to reality, rather than a technocratic desire to control and be continuously productive. Second, in contrast to the worker’s idealization of action and effort, the leisured soul relates to the world a receptive celebrating spirit. Third, leisure does not justify itself in terms of its function for the work-world. The leisured soul takes pleasure in what appears useless from the perspective of the work-world.

In brief, the leisured soul is a contemplative soul. But what exactly is involved in contemplation? This is a crucial question, especially given that there are many activities that today might pass for contemplation (e.g., mindfulness) but that only further bind the practitioner to the work-world. The second part of Pieper’s text, entitled “The Philosophical Act,” is important on this point. Here he makes clearer that a central component of contemplative leisure is the philosophical act. The latter is not just critique or disciplined thought regarding some particular aspect of the world (e.g., the philosophy of science, of language, ethics, and so forth). Rather, philosophy properly understood asks about the totality of being (or “world as a whole”) and, correlatively, the ground of the world as a whole (i.e. God). By doing so, it brings out into the open a constitutive element of human existence that the Umwelt-enclosed animals lack—namely, that we always stand in relation to the totality of being and its ultimate ground (God). In contrast to the Umwelt-enclosed animals, human beings are world-open and God-open. Philosophy is, so to speak, the guardian of this openness.

It is precisely through the philosophical act that we, so to speak, distance ourselves from the work-world. This is not a flight from it, however. It is rather a relativizing of the work-world in relation to the world as a whole and God.[17] As Pieper puts it: “The work-world is thereby rendered “‘transparent’ to the question-asker; it loses its compactness, its apparent completeness, its self-explanatory, obvious nature.”[18] What the work-world takes for granted is what the contemplative calls into question. The philosophical act thereby disrupts the tendency within the age of work for us to become enclosed in and bound to the work-world. Indeed, it renders us a kind of wayfarer or stranger within the work-world.

By relativizing the work-world in this manner, we do something that the Umwelt-enclosed animals cannot—namely, bring to awareness that our quasi-animal work-world is only a limited sector of reality as a whole. We thereby remind ourselves of our distinctively human openness and, by doing so, render the world open again to wonder. In fact, contemplation reaches its telos in a “cheerful affirmation by man of his own existence, of the world as a whole, and of God.”[19] This connection between leisure/contemplation, the world as a whole, and God grounds Pieper’s provocative—albeit tenuous—suggestions regarding the causes of the totalizing tendency of the work-world. In brief, the space into which the totalizing spreads is one marked by acedia, a vice that Aquinas describes as a sin against the Sabbath and an inability of the soul to rest in God. Acedia therefore does not give rise to idleness but rather to restless activity. It is an attempt to escape from ourselves once we have been seized by the “sadness of the world” (tristitia saeculi). Seen in this light, the spiritual root of the totalizing tendency of the work-world is metaphysical homelessness (i.e., “God-lessness”). The leisure-less age of work is, then, an age in which we have been collectively seized by the sadness of the world.

On ours being an age of metaphysical homelessness, Han and Pieper agree. Han calls this condition “world-lessness.” It names the increasing “fleetingness” of all things: “Not just human life, but the world in general is becoming radically fleeting.”[20] Han suggests a connection between world-lessness and God-lessness in a brief claim that the former is a consequence of the “denarrativization of the world.”[21] A central function of religion is to “narrativize” the world and thereby grant the lives of its practitioners a sense of structure, direction, meaning, closure, and so forth. Albeit implicitly (and following Arendt’s analysis), Han here again frames the issue in terms of an approximation of the animal. Animals are restricted to instinctual behavior, vital needs, and a corresponding multitasking mode of attention. Because of this, their Umwelten are marked precisely by fleetingness. A world-less and God-less achievement society is therefore one whose structure increasingly approximates the fleetingness of the animal Umwelt.

Although he does not refer directly to acedia, Han’s account of burnout within an increasingly world-less and God-less society reads as a description of the same phenomenon. Experienced as no longer being able to achieve, burnout is a self-reproach: “I am a failure.” The burnt-out self is “at war with itself.”[22] But an achievement society cannot accommodate such a breakdown. There is no place for the burnt-out self to go but to flee from itself back into the work-world. Our achievement society is, accordingly, increasingly more so a “doping” society.[23]

For both theoretical and personal reasons, I have deep sympathies with these texts. Something is indeed amiss with our relation to work, and Han and Pieper offer a distinctive vantage point on the situation. As I have suggested, this distinctiveness lies in pushing us beyond the ethical and economic toward a kind of inquiry that I have called philosophical anthropology. The latter asks a question that no doubt appears slightly naïve in our postmodern times—namely, what is the human? Philosophical anthropology answers this question by providing an account of those capacities and activities that are distinctively human and, correlatively, an account of what constitutes our species-specific mode of flourishing. This grants Han and Pieper a normative vantage point from which they can critique the “age of work” (Pieper) or the “burnout society” (Han), both of which are structured upon and reinforce homo laborans as their underlying philosophical anthropology.

As exhibited in both texts, philosophical anthropology always involves—whether explicitly or implicitly—claims that are metaphysical and theological in nature. The specific definitions of the human that philosophical anthropology trades in (e.g., homo sapiens, homo faber, homo religiosus, homo laborans, homo economicus, and so forth) are therefore not simply about the differences between human and other animal cognitive and affective capacities. Important though these differences may be for philosophical anthropology, this more limited task is, strictly speaking, that of comparative ethology. What is ultimately at stake in philosophical anthropology is more so worldviews and correlating human ideals (e.g., philosopher, worker, entrepreneur, saint, and so forth). It is the role of philosophical anthropology to draw out these interconnections. In this sense, it is a maximally interdisciplinary and thoroughly normative mode of inquiry.

Sympathies should, however, not get in the way of critical questioning. What are we to make of this mode of analysis? Is it not too ambitious in its scope and hence too recklessly sprawling at times? Are the various connections not far too tenuous? Is ours truly a God-less age? Do we not see in these texts the expression of a perspective that harbors a contempt for work (and the worker) and, because of this, exaggerates the present dangers? How much have the worker or entrepreneurial ideals in fact taken hold? Need contemplation and work always be placed in such a contrastive relation? Indeed, what counts as “work” or (authentic) “contemplation” for that matter? Correlatively, do these texts do justice to the entrepreneurial and worker ideals as well as to some of the goods that the “age of work” has brought about? I will leave these as questions, but it seems to me that both texts are vulnerable to critiques along these lines.

For those like myself who have sympathies with these texts and with the task of philosophical anthropology, let me conclude with two brief thoughts that go in a slightly different direction than the above questions would take us. The first thought is a puzzle about an absence in both texts—namely, that of Darwin. Granted, Han mentions Darwin, but he does so only once, and while quoting Arendt. In both texts, the governing way of framing human-animal differences seems to be that of Heidegger’s distinction between the human as world-forming (weltbildend) and the animal as poor-in-world (weltarm). It is a way of framing the differences that emerged out of Heidegger’s engagement with Uexküll. But when it comes to the dangerous aspects of the contemporary work-world and the philosophical anthropology undergirding it, it strikes me that it is the Darwinian construal of human nature and the natural world that is more relevant. The work-world within our burnout society is—in many but not all ways—a “Darwinized” work-world.[24]

Indeed, as Max Scheler argued in the early twentieth century, the emergence of the “age of work” is directly correlated with the emergence of the movement of philosophical pragmatism that was itself deeply indebted to Darwin. For pragmatists such as John Dewey, the human being is just another evolved animal whose various capacities can now only be seen in relation to practical action.[25] Add to this a materialist metaphysics and the ancient ideal of contemplation and the classic definition of the human being as homo sapiens is rendered naïve at best.[26] It seems to me, then, that a more rigorous critique of homo laborans as a philosophical anthropology must grapple with the various ways in which Darwinism has been co-opted to support it. I suspect that what Pieper calls the totalizing tendency of the work-world is not incidentally related to the emergence and influence of Darwinism, according to which everything is ultimately framed in terms of its practical function (adaptation) in relation to basic vital needs.[27]

The second question is this: do Han and Pieper do justice to the animals? I am worried that, like many who seek to clearly demarcate “the” human from “the” animals, they fall prey to a kind of caricature of our fellow animals and their Umwelten. Han characterizes the animal as incapable of contemplation, as restricted to a multi-tasking attention that is thoroughly geared toward here-and-now survival needs. Yet he also claims that the hyperactive “late modern animal laborans is anything but animalian.”[28] So what is it, then, to be an animal? Which animal exactly? What about the immense amount of time that certain animals spend in, say, sleep and play? Are—as Pieper suggests—their Umwelten structured solely around “vital” needs such as reproduction, nourishment, and so forth? Do animals not also sometimes just, so to speak, pass the time in their own kinds of leisurely playfulness? I do not have definitive answers to these questions at hand. But I have the strong suspicion that, at least in some cases, the Umwelten of other animals are far more “leisurely” than we might think—if we understand leisure more broadly than does Pieper. What is needed in order to resist the totalizing tendency of the work-world is, then, perhaps not simply a reassertion of what is distinctively human. Perhaps we can also relearn from our fellow animals what it means to be a finite creature who never “works” more than its God-ordained nature requires?

[1] Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society, trans. Erik Butler (Stanford, CA: Stanford Briefs, 2015), 5.

[2] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958), 322.

[3] Han, Burnout Society, 14.

[4] Ibid., 15.

[5] Ibid., 12.

[6] Ibid., 10.

[7] In Marx’s words: “[The alienated worker] only feels himself freely active in his animal functions—eating, drinking, procreating, or at most in his dwelling and in dressing-up, etc.; and in his human functions [i.e., labor] he no longer feels himself to be anything but an animal.” See Karl Marx, “Estranged Labor,” from his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844.

[8] There are reasons for distinguishing these, but, for the sake of this short essay, I will simply view them as interchangeable.

[9] Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 84.

[10] Given how relatively unknown Uexküll remains in the Anglophone context, a few brief words here are in order. Heavily influenced by Goethe, Uexküll’s Umweltlehre (“environmental theory”) by all means represents a romantic reaction against both the growing attempts in the early twentieth century to explain life processes within a mechanistic framework and the Darwinian construal of the animal world primarily in terms of the struggle for survival. Uexküll also explicitly frames his Umweltlehre as an application of Kant’s transcendental idealism to the animal domain. He had an immense impact upon continental philosophers (e.g., Martin Heidegger, Max Scheler, Helmuth Plessner, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Gilles Deleuze, to name but a few) and scientists (e.g., Konrad Lorenz, Adolf Portmann, to name but a few). It is important to point out that Uexküll was politically conservative, and, although he developed his main insights prior to the emergence of national socialism, he was an anti-Semite who showed Nazi sympathies (at least early on). A debate continues regarding the degree to which his Umweltlehre is influenced by his political views and just how deep his Nazi sympathies actually ran. The range of philosophers and scientists—with often radically different political views—who were influenced by his thought at least suggests that his political conservatism and Umweltlehre are separable to some degree, just as Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is separable to some degree from his own troubling views on progress, race, and colonialism. Indeed, Darwin’s ideas were far more fruitful for Nazi purposes than was Uexküll’s explicitly anti-Darwinian Umweltlehre. Interestingly, Uexküll is today receiving more attention than ever before within the Anglophone context from both philosophers and scientists alike. He is now widely recognized as a founding figure for ethology and biosemiotics. But discussions in the Anglophone context often tend to ignore Uexküll’s political views and the complex ways in which they entangle with his Umweltlehre. Any engagement with Uexküll must keep these political issues in mind.

[11] Pieper, Leisure, 102.

[12] Ibid., 102.

[13] Ibid., 111.

[14] Ibid., 117.

[15] Ibid., 61-62.

[16] Ibid., 50.

[17] What Pieper has in mind here is a pattern of questioning that constitutes philosophical inquiry. We might start with a work-world question along the lines of: “What is the economy? How does it work?” But philosophy in the proper sense will press on to questions such as: “Well, what is money for that matter and what ends ought it serve?” This will lead to deeper questions regarding human nature, and this in turn leads to metaphysical and theological questions. Through this line of inquiry, philosophy inevitably renders the work-world “strange.”

[18] Pieper, Leisure, 116.

[19] Ibid., 49.

[20] Han, Burnout, 18.

[21] Ibid., 18. Admittedly, I am doing some interpreting of Han’s claims at this point. See also p. 34 for brief reference to the sacred and the Sabbath. Han clearly sees a connection between world-lessness and a loss of the sense for the sacred.

[22] Ibid., 42.

[23] Ibid., 30. The idea here being that medication is the quickest means of re-integration into the work-world.

[24]As the late French economist Daniel Cohen claims, “In the lean world of modern firms, cooperation and reciprocity have become rarer. Rivalry among staff within the same company is encouraged” (Daniel Cohen, Homo Economicus, The (lost) Prophet of Modern Times, trans. Susan Emanuel [Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014], 22). However, I must agree with Cohen that such glorification of competition and rivalry does not do justice to Darwin’s own view of human nature and ethics. In this sense, such rivalry in the work-place is better characterized as “pseudo-Darwinian” in character.

[25] Max Scheler, Cognition and Work, trans. Zachary David (Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press, 2021).

[26] According to Scheler, the ancient ideal of contemplation and wisdom depends not only upon there being an intelligible world but also upon our having a capacity for “spiritual” acts that “are principally independent of the collectivity of our drive-related needs, of our particular human type of organization, as well as our particular practical manners of activity” (Ibid., 191). Only then can we really be open to the real essential structure of reality, which is what contemplation presupposes.

[27] I make this claim with real hesitancy, as I am fully aware of both the complex debates about what exactly constitutes “Darwinism” as well as the contemporary developments in evolutionary theory. Here we have to make a distinction between a Darwinian “philosophy of nature” versus contemporary evolutionary theory. Darwinism becomes something more than a philosophy of nature when it starts functioning as an all-encompassing “world-view.” When it does so, its consequences can, of course, be catastrophic (and have been catastrophic). In any case, I am not claiming that we in this age of work all adhere to an explicit Darwinian world-view. In fact, I think that—especially after World War II—Darwinism was largely rejected as a world-view. However—and this again is just a hypothesis that would require substantiation—, the one place where it may still function as a kind of underlying world-view (whether explicitly or not) is in the business world.

[28] Han, Burnout Society, 18.