Men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved, and who at the most can defend themselves if they are attacked; they are, on the contrary, creatures among whose instinctual endowments is to be reckoned a powerful share of aggressiveness. As a result, their neighbor is for them not only a potential helper or sexual object, but also someone who tempts them to satisfy their aggressiveness on him, to exploit his capacity for work without compensation, to use him sexually without his consent, to seize his possessions, to humiliate him, to cause him pain, to torture and to kill him. Homo homini lupus [man is a wolf to man]. Who, in the face of all his experience of life and of history, will have the courage to dispute this assertion?

—Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents

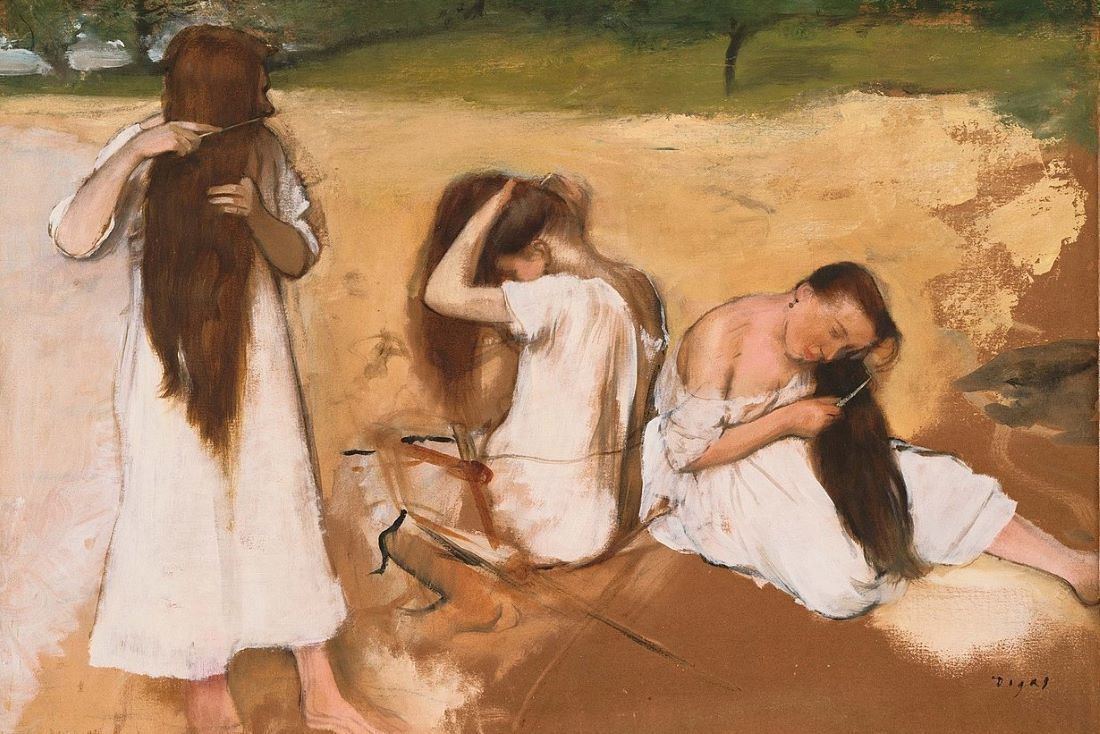

You can find a flock of Degas’s wax figures in the National Gallery of Art’s basement concourse, hidden in a dim marble room. Thanks to the shimmering composition of wax and clay, these archetypal women seem to shine with the sweat of their labors: the thrust of a dancer’s arabesque or a masseuse’s brusque kneading. They do not bear distinct facial features, and the intimation of eyes, noses, and lips conveys a kind of tender personalism, something private and real, the particular hidden out of regard for the holiness of an unclothed body.

I stumbled on Degas’s wax figures in my early twenties, after returning to Washington, DC, following a stint with an organization that served people in prostitution in El Alto, the mile-high slum above La Paz, Bolivia. Before Bolivia, I had rarely encountered violence. This stoked a tender, empathetic innocence about the purposes and stewardship of the human person, one that predisposed me to consider others first as friends: a heart, a mind, and a gendered body that contextualized a person but did not render them an object of sex.

It was with this interior disposition that I encountered the oversexualized tedium, misery, and humor of the El Alto red light district: the skinny legs of teenage girls huddled and waiting in a droning brothel disco; the chapped, glazed eyes of Altiplano grandmothers, weathered from high-altitude and harsh sexual encounters; and the constant parade of breasts, real and fake, a badge of pride especially for young women who had not yet nursed babies.

My innocence was received as curious, annoying, a marker of a certain kind of privilege. Still, in that place peopled predominantly with women abused by men in sex trafficking or acts of prostitution “chosen” in a devastatingly abject sphere of choices, we forged friendships and I felt oddly at home. So many women simply longed for female friends—to know and to be known with a sisterly affection, to laugh. And despite the sexual violence of their lonely dystopia, they still longed to know something generous, lasting, and loving of men.

Vaulted from El Alto’s muddy brothel streets back to the genteel striving of D.C. young adulthood, my heart and mind worked feverishly to make sense of the human body as I had encountered it in Bolivia. One afternoon, I walked from my Capitol Hill apartment down to the National Gallery of Art and found Degas’s wax figures waiting for me. They were simply women: clearly gendered and beautiful in their female forms, and so in some ways appreciable for a base sexual charge. But as they lingered in a bath or leaned easily on their hips, they inverted the feminine tedium and misery of El Alto and rose like innocent Eves in the happy privacy of the prelapsarian Garden: so fully female that their archetypal gift seemed to beg the counterbalance of a waiting Adam.

Over the years, I remembered Degas’s figures. My life became a typical D.C. boomerang existence, shuttling back and forth from the city to overseas projects addressing human trafficking, sexual violence, and the genocides of the new millennium. When I came back to D.C. after weeks or months away, I often went to visit the women, darting down to their West Building gallery for a long gaze or a quick turn, just to say hello.

Violence disfigures, in the act and in its resonance, but the desire for wholeness endures. Degas’s shapes seeded so deeply into my imagination that no matter where I was in the world, it was not unusual for me to think of the women and mimic them when I suddenly found myself taking up their remembered gestures. Toweling off my hip, looking at the sole of my foot, or lifting up my own long hair, I saw and felt my body as an echo of their wax bodies, and I shifted into their positions.

This happened in the privacy of foreign hotel rooms or apartments, after walking the muddy paths of Bangladesh’s Kutupalong Refugee Camp, home to perhaps thousands of Rohingya refugees who have survived genocidal sexual violence; or visiting the rickety sprawl of Kolkata’s infamous Sonagachi sex trafficking nexus, or crouching under a cashew tree to listen to the stories of Mozambican child rape survivors.

Mimicry was a way of rebuking the violence I glimpsed, of declaring in the hiddenness of my own heart—the seat of human freedom, a transcendent gift that violence wants to destroy—that the body can be held whole and entire, gendered but not exploitatively sexualized, tender and solitary and reserved as a gift that chooses the one who may receive it.

***

Violence robs its victim of the dignity of human freedom—or, in a Thomistic vein, the capacity to discern, choose, and act in the natural pursuit of truth, goodness, and happiness. It renders the body an impersonal cipher: a zero to which the aggressor may apply a value in a brutal exchange.

Human sexuality cultivates freedom in a unique way, because no matter the gender identities, expressions, or sex characteristics of the actors, the mutual exchange of the sexual act is perhaps the most vulnerable and total gift of self that a person can choose to make. The exchange inherent in the sexual act between men and women bears a distinct vulnerability because it holds the possibility of both unitive pleasure and new life. This possibility heightens the interior drama of freedom in sexual decision-making, especially for women, whose bodies radically surrender to the baffling inertia of creation.

Genocide’s end is decimation. A genocide victim bears value due to his or her affiliation with a nation, ethnicity, race, or religion. This value marks the victim for an exchange of identity for death. Genocide and sexual violence are intricately linked per the unique power the latter plays in effecting the former. Sexual violence inverts self-gift in thievery and unitive pleasure in pain. When male aggressors direct sexual violence at female victims in the context of genocide—with the ultimate aim of killing the victim and her community, rather than creating new life—we see a unique and full mockery of the sexual act. This mockery stirs a shame that often sears not only the individual victim, but also the beleaguered community—and so heightens the disgrace and terror of their corporate demise.

The genocidal aggressor’s concept of the valence of race, as a fixed identity rooted in the body, or religion, as a changeable identity rooted in allegiance, seems key to determining what kind of sexual violence the aggressor employs: rape, as a form of torture meant to amplify personal and communal agony in an expedient death, or sex trafficking, as a means of temporarily prolonging victims’ lives in order to multiply exchanges of sex for gain. Two key contrasting examples are Nazi soldiers’ rape of Jewish women during the Holocaust, and Islamic State sex trafficking of Yazidi women during this century’s genocide against Iraq’s religious minorities.

Throughout the 1920s, Hitler worked to socialize Rassenschande, or race defilement, the idea that sexual relations between Jews, other non-Aryans, and Germans poisoned German society. In some ways, this logic complicated the Nazi narrative that the Jews were a sub-human race, as it afforded Jews a precise power. But it also fortified the Nazis’ drive to destroy them. In 1935—when Germany’s Jewish community numbered about 500,000, or only .75% of the country’s total population—the Nuremberg Laws codified Rassenschande in The Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor. Initially, civil punishment stopped at prison or hard labor, but during World War II, a Rassenschande conviction could lead to death.

In truth, Rassenschande often led to death even in the years before the war—but only for Jewish women raped by Nazis, and not for their Nazi perpetrators. Dr. Steven T. Katz’s meticulous Thoughts on the Intersection of Rape and Rassenschande during the Holocaust shows the historic record bears ample, disturbing evidence that Nazis regularly—and often, immediately—killed the Jewish women whom they raped in brothels, ghettos, and concentration camps, and that Nazis regularly conducted rapes and murders in public or in proximity to victims’ agonized husbands, siblings, parents or community members.

In the torqued logic of Rassenschande, rape, and murder, the victim’s death conceptually cancelled out the rapist’s race defilement crime, as it eliminated the possibility that the victim might give birth to a Jewish-German child. Rassenschande logic also sanctioned a grotesque form of corporate torture in which the aggressor’s self-inflicted offenses against racial purity displaced rape as an honor crime to be cruelly and publicly avenged. Here, Dr. Na’ama Shik’s comment on sexual violence in Nazi concentration camps may be applied more broadly. As she says in Infinite Loneliness, her book of Auschwitz camp testimonies, at some point, Jewish women “ceased being ‘human women’” imbued with dignity “and became a wide-open bodily site that possessed signs of sex but contained no humanity”—no freedom to act, no gift to give, and no gift to receive.

While the Nazi logic of Rassenschande, rape, and death hinged on a presumed valence of race and urged the victim’s expedient murder, the logic behind Islamic State sex trafficking of Yazidi women presumed a valence of religion and rewarded aggressors who stewarded victims for monetary and morale gains. The October 2014 edition of Dabiq, the Islamic State’s online propaganda magazine, published an article entitled, “The Revival of Slavery Before the Hour.” The article declared the Islamic State’s intent to target the Yazidis, a religious minority that then constituted just 1-2% of Iraq’s total population. Islamic State deemed the Yazidis pagan infidels and promoted a Shariah law argument that justified enslavement and concubinage. But in order to be made fit for trafficking for forced marriage among Islamic State fighters, Yazidi women had to endure the indignity of forcible conversion to Islam.

The Dabiq article articulated an argument already in play at Islamic State’s August 2014 assault on Sinjar city and a series of small Yazidi villages. Nadia Murad’s memoir, The Last Girl, is a clear-eyed account of what happened to her and other Yazidi women who experienced Islamic State enslavement. Kidnapped from their ancestral homes, old women and young women were generally separated into two groups. The old women were immediately massacred, while the young women were transported to their first stop on the Islamic State slave market circuit. As detailed in Nadia’s book and other testimonies, young women were expendable but generally kept alive in order to facilitate the exchange of sex for gain—both the financial gain realized in slave markets, and the perverse morale gain Islamic State men realized in the sexual abuse of women who, despite conversion to Islam, bore a pagan stain and so served as approved receptacles for both genocidal hatred and sexual violence.

Tragically, Islamic State theology reinforced complex Yazidi beliefs regarding bloodlines and ethnic identity. Traditional Yazidi religion holds that women who engage in sex—whether consensual or forced—with non-Yazidis may be expelled from the Yazidi community. And only a child born of two Yazidi parents can claim Yazidi parentage. Baba Sheikh, a prominent member of the Yazidi Supreme Council, declared in 2014 that Islamic State sex trafficking survivors could return to the community, rather than face exile. But as recently as May 2019, he reaffirmed that traditional Yazidi bloodline rules still hold for children born to Islamic State fathers, and that the children must be left behind if their mothers wish to be welcomed back. Under these terms, many Yazidi survivors of sex trafficking find their freedom doubly circumscribed: assailed first by their traffickers’ brutal abuse and then restricted by the culture they long to honor.

***

Enmity between men and women animates the Creation stories of many of the world’s faiths, including the Jewish and Yazidi religions, where Adam and Eve spar bitterly over culpability in original sin, on one hand, and vie to give life on the other. These archetypal figures and our own experiences of sex, conflict, and violence undergird a primal desire to witness the union between men and women not as a site of struggle, destruction, and death, but as a wellspring of life. We want to see that we as human beings may freely give ourselves to each other and be received: not only for our sexual capacity but also for the many gifts we harbor in our minds, hearts, wills, and imaginations.

In my love for Degas’s wax figures, it took me a few years to venture beyond their room in the National Gallery of Art and see the other works in the main sculpture hall. When I did, I found a parade of imposing Rodin figures. Even when he presents female forms, Rodin’s sculptures always strike me as trending toward the classically masculine, with the basic musculature of the human body expanded and broadened. This holds so true for my eye that the first time I stood before Rodin’s “Hand of God” I mistook the broad-shouldered Eve figure for Adam.

Then, in slowly circling its glass gazing box, I saw the classical distinctions in their physiques and I realized that of the two bodies bound in a primal kiss, it was a woman flying first from God’s hand and a man crowning in the curve of her stomach and breasts—as if, in emerging from chaos, his first place of rest was the womb from which all other humans would spring.

There is something in the body that entices us to conquer, to take up our freedom as a weapon, to make sense of human weakness by denying it in ourselves or obliterating it in others. And there is something in the body that invites us to make our own freedom a governor of that violent impulse, a steward that acknowledges the wages of disfigurement and asks us, instead, to consent to the entrustment of the gift.

This essay is based on remarks delivered at the Religious Freedom Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom Education in October 2019.