The modern project has been animated, to a large extent, by a resentment of dependence—a revolt against the creaturely conditions and cultural constraints that have shaped and thereby limited our pursuits of self-fulfillment. This antipathy for dependence is not, of course, an exclusively modern phenomenon. Indeed, as the opening chapters of the book of Genesis seem to suggest, it was an important feature of humanity’s original undoing: the desire to claim for oneself that which was always already available in the form of a divine gift. In modernity, however, this resentment has become something like a defining principle.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) thus defines and commends “enlightenment” as the ability to think for oneself without lazily or fearfully submitting to the guidance of others. The motto of the Enlightenment, Kant declares, is “Sapere aude! Have courage to use your own understanding!’[1] Writing half a century later from the other side of the Atlantic (and giving voice to that distinct brand of individualism which has long characterized the American mythos), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) extols self-reliance as the highest ideal, the most “godlike” of all human traits. “Trust thyself,” Emerson insists, “every heart vibrates to that iron string.” One must abide by her own convictions without regard for communal expectations or social conventions, for society everywhere conspires against the creative self-expression of its individual members.[2]

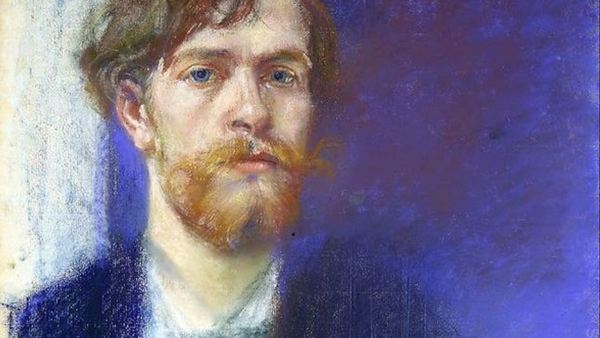

This resentment is taken to its extreme in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), for whom the will to power is the all-consuming “good.” For Nietzsche, the individual is (or at least ought to be) a law unto himself, answerable to no higher standard and accountable to no one else. Human existence is, for Nietzsche, the endless drive of self-assertion in pursuit of ever greater power and “efficiency.”[3]

We encounter a less sophisticated, though arguably more influential, version of the modern disdain of dependence in the fiction and essays of Ayn Rand (1905-1982), whose writings have been championed by a number of prominent Anglo-American economists and politicians on the right as offering the most convincing “moral” argument for laissez-faire capitalism. The world portrayed in works like The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged is one in which the heroism of creative individualism is constantly under threat by government intervention and the parasitism of the weak. “The second-hander [one who depends on the ingenuity of another] has used altruism as a weapon of exploitation,” declares the protagonist of The Fountainhead, Howard Roark, “and reversed the base of mankind’s moral principles. Men have been taught every precept that destroys the creator [the innovator and entrepreneur]. Men have been taught that dependence is a virtue.”[4]

Sapere aude! Trust thyself! The will to power! Individualism! What becomes of a people motivated primarily by such ideals? To begin, the resentment of dependence quickly gives rise to resentment of the dependent. The privileging of self-reliance as the highest human ideal inevitably diminishes and dehumanizes those whose lives are most transparently in need of the care and support of others. The impoverished are thus scorned as mere “takers” of public resources, while the elderly, the ill, and the disabled are often portrayed as (and made to feel like) burdens on their family and caregivers. This conflation of dependence and the dependent as a common object of resentment is already evident in the writings of Rand and Nietzsche. According to Rand, those at the bottom of “the intellectual pyramid,” those who, left to themselves, would “starve in [their] hopeless ineptitude,” contribute nothing to those above them, damning the strong instead to a pattern of exploitation.[5]

For Nietzsche, meanwhile, nothing threatens the will to power more than pity. “The weak and the botched shall perish,” he declares. “And they ought even to be helped to perish.”[6] To do otherwise, to have compassion on the weak, would only spread the disease of their suffering. It is not surprising, therefore, that both thinkers express hostility towards Christianity, which Rand disparages as “the best kindergarten for Communism possible,” and Nietzsche as “the revolt of all things that crawl on their bellies against everything that is lofty.” The will to power cannot pray nor render praise to a God who takes the form of a slave (Phil 2:7) and identifies explicitly with “the least of these” (Matt 25:40).

The dependent—those broadly assumed to receive more than they give to others—may be the most obvious victims of the modern idolization of independence, but they are scarcely the only ones. Disdain for dependence threatens both our common human life and, as we have become all too painfully aware in recent years, the world we inhabit together. It leads us to see others as either irrelevant to our pursuits of self-fulfillment (in which case they can be safely ignored), or as a threat to self-fulfillment (in which case they must be heroically overcome), or as instrumental to our fulfillment (in which case they become absorbed into our own projects of self-actualization). Missing in every case is that sense of responsibility for others that arises from the awareness of our interdependence.

The resentment of dependence leads likewise to the exploitation of the natural world. Impatient with the limits we encounter in the world around us (the time between harvests, the carrying capacity of the land, the slow growth to maturation in livestock, etc.), we employ every political, economic, and technological means available to mitigate our dependence on nature’s limits. Increased agricultural inputs (synthetic pesticides and fertilizers) lead to quicker and more bountiful harvests. Global trade and the growing hegemony of supra-national corporations allow for the consumption of a greater number of goods without the constraints of local seasons and climate. Advances in biotechnology (the use of growth hormones and genetic modification) enable a swifter transition from calf to beef.

In the short term, therefore, it would appear that we have indeed successfully circumvented the laws and limits of nature, enabling greater production, consumption, and ultimately profit. We are however now witnessing the first fruits of the disastrous long-term effects of such an exploitative and “extractivist” approach. The chemical warfare that we have waged against agricultural pests and diseases has poisoned our water and soil in turn. The hormones that we have infused into our livestock have greatly diminished their health and increased their suffering. The gross amounts of fossil fuel required to transport “out of season” produce across oceans and continents has polluted the air and contributed to the planet’s warming. In short, our attempts to transcend the limits of nature have greatly increased the natural limitations that now confront us (more extreme weather events, fewer natural “resources,” depleted topsoil, etc.). We are increasingly enslaved to the very conditions that we have introduced into nature in our pursuit of greater independence from nature.

None of this should come as a surprise to those steeped in the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. At root, the resentment of dependence is a resentment of our own creatureliness. It is destructive precisely because it is untrue, placing us in contradiction with the order of things that God has made. To be a creature is to belong within a network of interdependent relations which are created and sustained by God, and which find their fulfilment in the loving praise of God (e.g., Psalm 148:3–5; cf. Psalm 124; 140). Human flourishing is therefore bound up with the flourishing of this created order. To rebel against our creatureliness, to seek to place ourselves over and above (and thus ultimately against) the created order is to alienate ourselves from our creator and from the network of creaturely relations through which we are formed and to which we are, in an important sense, responsible.

The result of such rebellion is not simply the self-destruction of the individual, but, as we observed above, the dissolution of human relations and the devastation of the natural world. What is required is therefore a rediscovery and restoration of our creatureliness, the reestablishment of a more convivial way of being human in which our flourishing is brought about only by the right ordering of our relations to God, others, and the world we inhabit.

The opening chapters of the book of Genesis provide a rich theological exploration of the shape of humanity’s creatureliness (the unique vocation of human beings within God’s created order) and the cause and consequences of humanity’s rebellion against this calling. Genesis 1 begins with the affirmation that all things—the sun and stars, the sea and sky, the seed-bearing plants and swarms of living creatures—owe their existence to God. God alone is independent of creaturely conditions, self-caused, and so fully replete in Godself. All other beings are beings by participation in God (the one in whom “we live and move and have our being”; Acts 17:28), spoken into existence by God’s Word (Gen 1:3–26; John 1:3), and sustained by God’s life-giving Spirit (Ps 104:30). For this reason, God declares that everything God has made is good, reflecting in a myriad of finite and complementary ways the infinite beauty and goodness of God.

In the creation account offered in the first chapter of Genesis, human beings are created last among God’s creatures and are said to be made uniquely in God’s own image (1:26–27). Though Christian anthropology has tended to fixate on the imago Dei as the key to interpreting the distinctiveness and vocation of human beings, the precise manner of humanity’s resemblance to God is not immediately clear from this passage. What is clear is that human beings are called to play a unique role within God’s created order, to exercise “dominion” among God’s creatures (1:26) in such a way as to represent, serve, and carry out God’s good purposes for creation. As Oliver O’Donovan observes, the enactment of humanity’s vocation “is a necessary condition for the rest of creation to fulfill its own ordering. His [the human being’s] rule is the rule which liberates other beings to be, to be in themselves, to be for others, and to be for God.”[7]

Human beings do not, of course, exercise this vocation in isolation from God, as though God relinquishes the governance of creation to human beings to reign in God’s absence. God remains actively and intimately involved in creation, nourishing and directing all things to their appointed ends. “O Lord, how manifold are your works!” declares the Psalmist. “In wisdom you have made them all . . . These all look to you to give them their food in due season; when you give to them, they gather it up; when you open your hand, they are filled with good things” (Ps 104: 24, 27–28). Human beings, meanwhile, must rely continually upon God if they are to faithfully perform their vocation as God’s image-bearers. For it is only in seeing God, we read in the First Letter of John, that we come to bear the divine likeness (1 John 3:2). In other words, attending rightly to creation is contingent upon an abiding attentiveness to God.

Genesis 2 picks up on and further develops these themes through an exploration of humanity’s kinship and responsibility to non-human nature. Like all living creatures, human beings are formed from the earth (2:7; cf. 2:9, 19), suggesting their dependence, not simply on the creativity of God but on the fertility of the soil. Humanity’s intimate relation to the earth is further emphasized by the etymological association of the first human being and the soil from which he emerges: “the Lord God formed man [adam] from the dust of the ground [adama], and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being” (2:7).[8] Human beings are “earthlings,” vivified by the Spirit of God but nevertheless grounded in the story of the soil. It is not surprising, therefore, that humanity’s vocation is likewise portrayed in Genesis 2 in express relation to the land. “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it” (2:15). These two verbs (translated in the NRSV as “to till” and “to keep”) are closely allied in Gen 2:15, suggesting a studied service of the land to which Adam has been entrusted.

According to Ellen Davis, the Hebrew term to till is perhaps better translated here as “to work,” or even “to work for.”[9] To work for the land is to devote oneself to serving its needs, striving to protect and ensure its health and fertility (what the ecologist Aldo Leopold describes as “the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community”).[10] This work of “tilling” is facilitated by “keeping” the land, a verb used elsewhere in the Hebrew scriptures to denote “observing,” that is, learning from something and adhering to it (as in keeping/observing the Sabbath; Ex 31:13).[11] We serve the land best, in other words, by continually attending to the orders of relations among its various members. As Pope Francis notes, “This responsibility for God’s earth means that human beings, endowed with intelligence, must respect the laws of nature and the delicate equilibria existing between the creatures of this world, for “he commanded and they were created; and he established them forever and ever; he fixed their bounds and he set a law which cannot pass away” (Ps 148:5b–6).[12]

In Aldo Leopold’s memorable phrase, in order to care for creation, human beings must learn to “think like a mountain” (or a deciduous forest, or a prairie, or, in the case of Adam and Eve, a garden in Eden).[13] According to Genesis 2, there is, therefore, a relation of mutual dependence between human beings and the land: humans depend upon the fertility of the soil, and the soil’s fertility depends in turn on the work of human beings.[14]

What emerges from the first two chapters of Genesis is thus a vision of creaturely flourishing in which all things are dependent on God, human beings are dependent on the earth and on their fellowship with one another (belonging intimately to one another and collaborating in the performance of their common vocation; 1:28; 2:18), and the land is dependent on the faithful dominion of human beings. It is only when human beings rebel against their creatureliness, when they seek to become “like God” (3:5, 22), divinely independent, that this original vision of paradise is distorted and the relations originally adhering among God’s creatures become disordered.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer argues in his commentary on Genesis 3, humankind “now lives out of its own resources, creates its own life, is its own creator . . . Thereby its creatureliness is eliminated, destroyed. Adam is no longer a creature. Adam has torn himself away from his creatureliness.”[15] In tearing themselves away from their creatureliness, in seeking to be their own “origin,” as Bonhoeffer writes elsewhere, human beings cut themselves off from the source of life, thereby subjecting themselves and the whole of creation to the economy of death.[16] This results, in the first instance, in a state of inner discord, the disordering of humanity’s desires such that we come to demand more of other creatures than they could ever possibly give (thus frustrating us to no end and exploiting the natural world in the process). To this disruption within human beings corresponds a disruption between human beings. Humans become alienated from one another, ashamed of their vulnerability, and distrustful of their exposure to one another (Gen 3:7).

This social disruption manifests itself further in relations of domination, portrayed in Genesis 3 as the curse of patriarchal rule (3:16). As Henri de Lubac laments, “humanity which ought to constitute a harmonious whole, in which ‘mine’ and ‘thine’ would be no contradiction, is turned into a multitude of individuals . . . all of whom show violently discordant inclinations.”[17] Finally, the soil itself comes to bear and reciprocate the trauma of humanity’s rebellion: “cursed is the ground because of you,” God declares to Adam (3:17). And again, following the murder of Abel by his brother Cain, “You are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength” (4:11–12a). In one sense, we can read these passages as direct punishments from God for humanity’s disobedience.

As we read elsewhere in scripture, the land’s fruitfulness is contingent upon Israel’s faithfulness, such that a failure to obey results in the land’s failure to yield its produce (Lev 26:20). In another sense, however, these passages indicate the “natural” consequences of humanity’s dereliction of its creaturely vocation. The distortion of humanity’s dominion leads inevitably to nature’s ruin. The mutually dependent relation between human beings and non-human nature becomes mutually destructive.

In the face of such disorder and destruction, the scriptures offer both a word of judgment and a word of promise. “The earth lies polluted under its inhabitants,” declares the prophet Isaiah, “for they have transgressed laws, violated the statutes, broken the everlasting covenant. Therefore a curse devours the earth, and its inhabitants suffer for their guilt; therefore the inhabitants of the earth dwindled, and few people are left” (Isa 24:5–6). This curse will not however have the last word (cf. Isa 43:19–21). Though human beings have renounced their vocation, God has not abandoned the creation to disintegration. For this reason, the one through whom “all things came into being” (John 1:3) and in whom “all things hold together” (Col 1:17) entered fully into our creatureliness, “becoming a curse for us” (that is, taking upon himself the violent consequences of our rebellion; Gal 3:13) and reorienting the created order back to its divine source.

The Christian faith thus offers a vision of creaturely flourishing that is centered on and accomplished by the person and works of Jesus Christ. This vision is staggering in both its particularity and its universality. At a particular time, in a particular place, through a singular human life, God heals and fulfills the entire created order. “For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell,” writes the apostle Paul, “and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross” (Col 1:20; emphasis added).

To be “in Christ” is therefore to know oneself as the recipient of a gift beyond measure. This gift is at once the gift of “new life” (2 Cor.5:17), a new way of being in relation to God and other creatures which we could never anticipate and for which we have no positive claim, and the revelation of the source and shape of our abiding creatureliness. In Christ, we rediscover and indeed deepen the bond of our dependence on the creative love of God. As Rowan Williams states, “We find our nature as loved creatures through the experience of being redeemed creatures. That we can be saved only by sheer gift is the revelation that gives us access to the unknown but always presupposed ground of all our distinctly human activity, the ground in gift, in the turning of God to what is not God in uncaused love.”[18] To live according to this gift, to receive and participate in Christ’s restorative work, means renouncing our self-destructive ambition for autonomy. It means leaning into our dependence upon God and the networks of creaturely interdependence to which we have been entrusted.

Among such networks of creaturely interdependence, the Church is the primary location in which the reunification accomplished in Jesus Christ is realized and revealed. The Church is the community shaped by the telling of what Christ has done for the created order and what Christ therefore makes possible here and now. It is the context within which our imaginations, our moral convictions, and our affections are formed by the hearing and telling of these stories, and where we come to know ourselves as both recipients and instruments of Christ’s restorative work (see 2 Cor 5:18–19).

The Church is where our sense of dependence and our desires are opened up beyond our networks of creaturely relations to their divine source (Matt 6:25–30). For it is here that we come to discover and acknowledge that “every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift is from above” (James 1:17a). It is in the Church, therefore, that we are ultimately schooled in our dependence on the loving care of God and our responsibility for extending that care to other creatures.

As we are told repeatedly throughout the New Testament, moreover, the Church is not simply the community from which we learn of our dependence on Christ. It is also, in a crucial sense, the context within which that dependence is lived out. We are dependent on Christ, in other words, in and through our dependence on the Church, “which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all” (Eph 1:23; cf. Rom 12:4–5; 1 Cor 12:12–27; 2 Cor 6:16; Col 1:18–24). As Henri de Lubac argues, “If Christ is the sacrament of God, the Church is for us the sacrament of Christ; she represents him, in the full and ancient meaning of the term; she really makes him present.”[19] This mediated dependence is experienced perhaps most vividly in the mystery of the Sacraments—those creaturely signs which have been entrusted to the Church by Christ and through which we are made participants in his ongoing work.

Through the waters of baptism, for instance, the “old self” (what Michael Ramsey describes as “the self-centered nexus of appetites and impulses”) is put to death in order that we might live anew in the power of Christ’s resurrection (Rom 6:3–4).[20] In baptism we thus renounce the renunciation of our creatureliness, rooting ourselves in and reordering our lives to God. Similarly in the Eucharist, bread (“which earth has given”) and wine (“fruit of the vine”) become creaturely instruments of Christ’s restorative work. In the reception of these gifts, we are united to one another precisely because we are united in common to Christ. “Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:17). Our ecclesial dependence on Christ is not, of course, limited to the Church’s sacramental ministry.

We are likewise dependent on Christ in and through the various members of his body, receiving Christ’s love from each other and freely offering that same love in return. Within the communion of saints, therefore, we discover the depths of our interdependence. No relationship within the Church is characterized purely by giving on one side and receiving on the other. For, “God has so arranged the body,” writes the apostle Paul, that “the members may have the same care for one another” (1 Cor 12:24–25; emphasis added). The wealthier member thus deludes himself if, in his monetary giving to the poor, he considers himself the exclusive (or even primary) benefactor in this exchange. For, as Augustine argues, the impoverished likewise cares for the wealthy precisely in helping to alleviate him of the “burden” of his wealth, a burden which may otherwise inhibit his love of God.[21]

The Church’s vocation is therefore to live in the light of “the reconciliation of all things” in Jesus Christ, bearing witness to what he has already accomplished and devoting itself to his ongoing work in the world. In its worship, and in the celebration of the Eucharist in particular, the Church performs humanity’s abiding role within and for the created order of offering “the praise of God to which the whole creation is summoned.”[22] The Church is likewise called to exercise that “studied service” of the created order to which humanity was tasked “in the beginning,” humbly attending to the networks of creaturely relations to which its members belong and working to ensure their flourishing.

This work is, in one sense, inescapably local on account of both the varying needs of different contexts and our limited capacity for responsible care. As Augustine notes, “All people should be loved equally. But you cannot do good to all people equally, so you should take particular thought for those who, as if by lot, happen to be particularly close to you in terms of place, time, or any other circumstances.”[23] So it is with the created order. All of creation is worthy of our care, but one cannot do good to all places equally. The local church must therefore devote itself to serving the particular needs of its particular place in the world. This is not, however, to encourage the kind of parochialism that is indifferent to social and ecological degradation so long as it remains across the border or on the other side of the fence. Such myopia overlooks, in the first instance, the extent to which the whole created order is interconnected.

As the current environmental crisis has taught us, sustained abuse of the natural world in one place can threaten people and places at great remove. Moreover, the Church’s vision of creaturely flourishing is indelibly catholic, “embracing everything, leaving nothing out.”[24] Its mission is therefore universal, proclaiming and struggling to realize in all times and in all places an order restored by love. This universal restoration is not, of course, contingent upon the Church’s efforts, as if we were the ones ultimately responsible for guiding the cosmos to its appointed goal. Here again we acknowledge our dependence on God; the same one who created all things in the beginning, and reconciled all things in Christ, will restore all things in the end.

As Samuel Wells argues, reflecting on the work of Stanley Hauerwas, “The world has been saved. Its destiny does not hang in the balance, waiting for the Church’s decisive and timely intervention to tip the scales . . . The Church does not make the difference. The Church lives in the difference Christ has made.”[25] To live in the difference that Christ has made is to gladly accept our place in the created order, gratefully acknowledging our dependence on God, and “living together” in a spirit of generosity and fellowship with all to whom we belong.

[1] Immanuel Kant, ‘An Answer to the Question: “What is Enlightenment?”,’ H. S. Reiss, ed., Kant: Political Writings, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 54–60.

[2] Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance,” Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Major Prose (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 128–30.

[3] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist, trans. Anthony M. Ludovici (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2000), 4.

[4] Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968), 712.

[5] Rand, Atlas Shrugged (New York: Dutton, 1957), 1065.

[6] Nietzsche, The Antichrist, 4.

[7] Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and the Moral Order: An Outline for Evangelical Ethics (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1986), 38.

[8] See Ellen Davis, Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture: An Agrarian Reading of the Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 29.

[9] Ibid. Cf. Wirzba, The Paradise of God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 30.

[10] Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 211.

[11] Davis, Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, 30.

[12] Francis, Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2015), 51 (§ 68).

[13] Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, 123.

[14] See Wirzba, The Paradise of God, 31.

[15] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Creation and Fall: A Theological Exposition of Genesis 1–3 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), 115.

[16] Bonhoeffer, Ethics (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 299–303.

[17] Henri de Lubac, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 33–34.

[18] Rowan Williams, On Augustine (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 175

[19] Henri de Lubac, Catholicism, 76.

[20] Michael Ramsey, The Gospel and the Catholic Church (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009), 29.

[21] Augustine, De disciplina christiana, 8; quoted in Sarah Stewart-Kroeker, Pilgrimage as Moral and Aesthetic Formation in Augustine’s Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 213–224.

[22] O’Donovan, Resurrection and the Moral Order, 38.

[23] Augustine, On Christian Teaching (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 20.

[24] Hans Urs von Balthasar, In the Fullness of Faith: On the Centrality of the Distinctly Catholic (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 27.

[25] Samuel Wells, “The Difference Christ Makes,” Charles M. Collier, ed., The Difference Christ Makes: Celebrating the Life, Work, and Friendship of Stanley Hauerwas (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015), 18.