Blaise Pascal wrote: “How I hate these stupidities: of not believing in the Eucharist, etc. If the Gospel is true, if Jesus Christ is God, where is the difficulty?” (Pensées §199). Pascal’s point was that if one accepts the rather incredible premise that there is a God who loves the universe and called it into being from nothing, and the further, even more incredible, premise that this God became flesh and dwelt among us in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, and in Jesus suffered rejection and torture and death and moreover conquered death and rose from the grave and has sent the Holy Spirit into our hearts, then why would one decide to draw the line at the claim that this God makes himself present to us under the appearances of bread and wine? Why would one say: “I am willing to believe all of this pretty unbelievable stuff, but this I will not believe?” Why would one believe that God could make something out of nothing but could not make the body of Christ out of bread? Why would one believe that God could appear among us as a squalling baby or a tormented and crucified man but could not appear among us under the appearances of bread and wine? Why would one believe that the God who could not be held by death could be hobbled by the laws of physics?

Pascal’s words, though a bit harsh, might seem to capture one aspect of the spirit of the ongoing “Eucharistic Revival” in the Catholic Church in the United States—a revival promoted by the bishops that will culminate in a national Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis in July of 2024. Pascal thought that if one believed in the Gospel, it was inexplicable that one would not believe in the Eucharist. Though we may stop short of describing such disbelief as “stupidity” (twenty-first-century people being a bit more polite and a bit less polemic than the people of the seventeenth century), his puzzlement is echoed by those of us—bishops, priests, deacons, and laity—who fail to see how one could identify as Catholic and not whole-heartedly embrace the Catholic belief that the Eucharist truly is Christ: body and blood, soul and divinity. Yet Catholic opinion, as measured by polls, and Catholic practice, as measured by declining numbers attending Mass, seem to suggest that this is the case for many self-identified Catholics.

But perhaps Pascal was being a bit unfair to those who doubt the Eucharist, and perhaps we who embrace Catholic teaching are being a bit unfair as well. Perhaps Christ’s presence in the Eucharist actually is a hard belief to accept—harder to accept in some ways than belief in God and Jesus. After all, Jesus lived long ago, and the creation of the universe was even longer ago, and somehow the distance of time can make incredible things easier to believe. Also, the notion of creation from nothing is so difficult to grasp that we might be inclined to shrug and say, “whatever,” and the story of Jesus is enough like legends from the ancient past about heroes and heroines that we can sort of half-believe it. Maybe with these incredible things we can slide by with half-belief and a shrug.

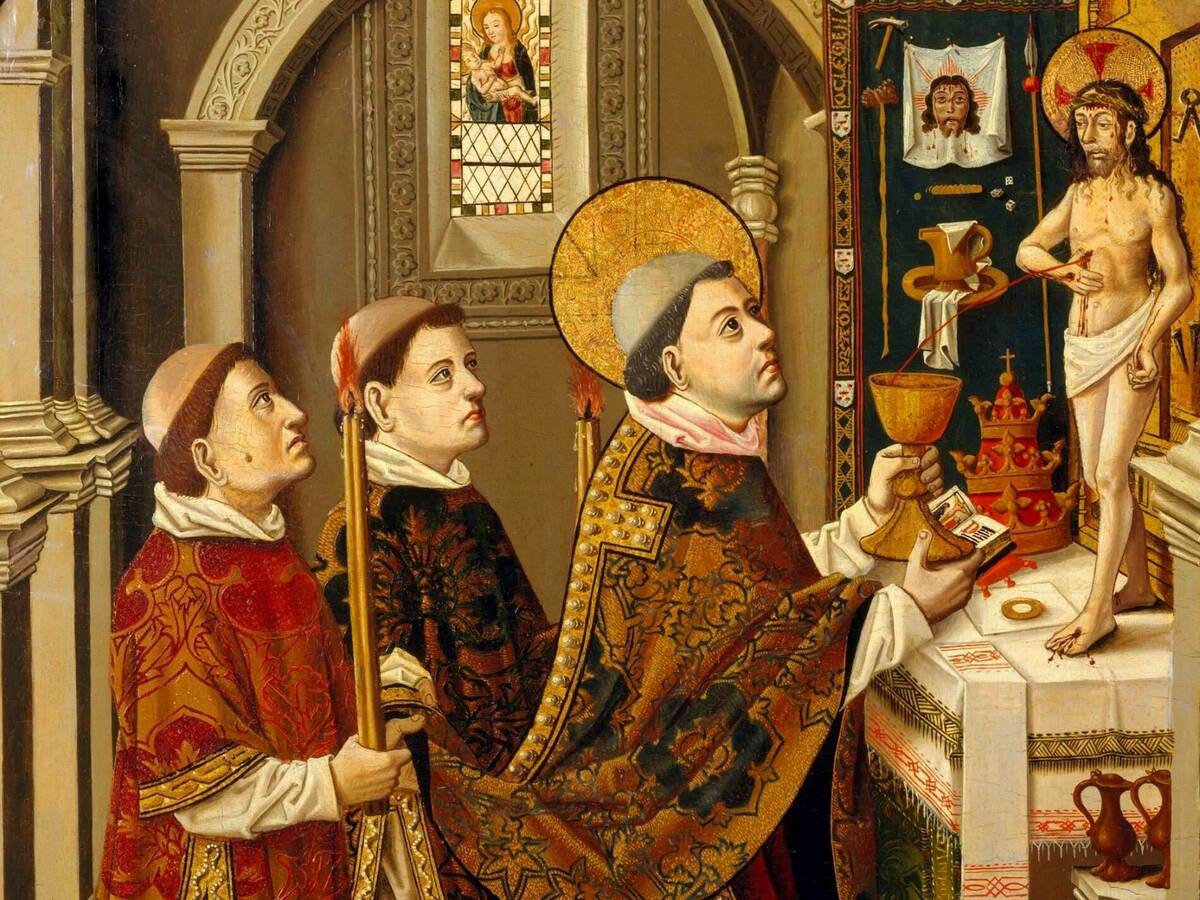

But what we are expected to believe concerning the Eucharist seems different. The Catholic claim about the Eucharist is not a claim about the past, but about the present (the same is, of course, true of claims about creation and the Incarnation, but we can more easily fool ourselves into thinking that this is not the case). It makes a claim about something that is here, now, right before our eyes. And yet, our eyes seem to be of little help; our hands and noses and tastebuds seem of little help. For we see nothing but bread and wine, we feel and smell and taste nothing but bread and wine. All we have is our ears that hear the words of Jesus spoken by the priest: “This is my body, which will be given up for you . . . This is the chalice of my blood, the blood of the new and eternal covenant.”

These words call forth our faith, but faith is a difficult gift, because faith is the gift of saying “yes” to that which remains hidden from us, and our human nature seems to resist accepting what is hidden. You can see this in the small child who, repeatedly and persistently, keeps asking “how” and “why.” How does the moon stay up in the sky? How are babies born? Why is ice cold? Why do I have to go to school? We want things explained; we want to know how they work; we want to know their reason before we say “yes” to them. But faith suspends us in an uncomfortable place, poised between the “how” and “why” and the “yes,” between unknowing and knowing. Faith is the gift by which we say “yes” without knowing “how” or “why.” Or, we can use our minds to gain some insight. We can think through what the Eucharist is not—it is not a second Incarnation, it is not God tricking us with disguises, it is not a kind of re-enactment of the Last Supper or a Christian version of Memorial Day—but when it comes to what it is, we, in the end, must rest in the words of Christ: “This is my body . . . this is my blood.” We must rest in these words because we trust him, because we believe that he is the one who can make them true, that he is the one from whom time and distance and even death cannot separate us.

But trust is hard, especially these days, so we might be somewhat tolerant of those who cannot trust, who cannot believe. Our present penchant for conspiracy theories—of all ideological stripes and political persuasions—is a sign that we think something is being hidden from us, but we do not trust those in power to be honest with us as to what that is. We are not willing to say “yes” to the official story. And, of course, we do have reasons for that lack of trust. Whether in government or in the Church, we have seen leaders who have bent or even broken the truth for their private advantage or institutional preservation. I do not know if people in power lie more now than they used to, but we certainly hear about their lies a lot more than we used to. In fact, due to various forms of social media, we hear a lot more about everything: you can easily find voices to support whatever suspicions you might harbor. And so, trust erodes, and with the erosion of trust comes the erosion of faith.

As I said, we have heard a lot in recent years about the erosion of faith in the Eucharist. Poll results indicating such an erosion might be a result, as some have suggested, of badly phrased questions: questions that pose false choices between the real and the symbolic or between presence and hiddenness. But the declining numbers of those attending Mass suggest that these polls reflect some real erosion of faith. And the solution to this erosion of faith is not simply more and better catechesis, as if we only need to explain better the Church’s teaching on the Eucharist. More and better catechesis is a good thing, but it is not enough for a true Eucharistic revival, because trust in the Church has eroded, and it is through the Church that we hear the words of Christ that call forth our faith and in which our faith rests: “This is my body . . . this is my blood.” People, it seems, are unwilling to say “yes” to the official story of what these words mean.

In part, this erosion is simply one facet of the more general erosion of trust in our world; and, in part, it is a result of very specific misdeeds on the part of some leaders in the Church: misdeeds specifically by those who speak the words of Christ in a sacramental context. But whether we see it as part of a more general cultural malaise or as something specific to the Church—and I think we need to see it as both—this loss of trust is at the heart of the erosion of faith. And the solution to a loss of trust is not more and better catechesis, since catechesis only works where trust is present.

In the end, of course, faith is a gift and there is nothing we poor humans can do to force people to believe, to make them trust, to revive their faith. But the gift of faith that God plants can flourish or languish depending on the environment in which it is planted. The fostering of such an environment depends partly on the leadership of the Church, on the clergy and their integrity. It depends on being forthright about our flaws and on holding ourselves accountable to each other and to God’s people.

But it depends on ordinary Catholics as well. Do all of us live our lives in a way that gives credibility to our claims? The famously disbelieving Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote of Christians: “They would have to sing better songs for me to believe in their redeemer: his disciples would have to look more redeemed” (Thus Spake Zarathustra, chapter 26). Do we look redeemed? Do we sing our songs joyfully? Do we live like those who have feasted on the bread of heaven and have drunk deeply from the cup of gladness? Do we give the world reason to believe that truth himself speaks truly when he speaks those words through human lips: “This is my body . . . this is my blood”?

Our faith in the Eucharist is in some sense a test of the integrity of our faith as a whole. As I have said, by nature we want to know “how” and “why” and faith is a matter of saying “yes” to something without knowing how or why it is true. And in the case of the Eucharist, this is particularly true, which is why St. Thomas Aquinas said that saying “yes” to the Eucharistic presence of Christ is the perfection of the virtue of faith (ST III q. 75 a. 1). The “how” of the Eucharist is hidden from us because we cannot wrap our minds around how the living resurrected Christ can make himself present to us under the appearances of bread and wine. We can come up with terms like “real presence” and “transubstantiation,” but these are more ways of stating that Christ is present than they are explanations of how he is present.

Yet, as mysterious as the “how” of Christ’s presence is, the “why” is even more mysterious. If we ask why Christ is present to us body and blood, soul and divinity under the appearances of bread and wine, the only answer we can give is because he loves us so much that he does not want us to be parted from him. And this is really quite unbelievable, for it seems impossible that the creator of the universe would make himself present to his creatures in such a way that we could take him into ourselves, that we could contain the one who contains all things. But Aquinas says that this is in fact supremely fitting for one who loves perfectly and who calls us into friendship with him.

For, he says, it is fitting that friends should be present to each other in a bodily way (something that we all learned during the pandemic when we were physically absent from so many of those we loved). Thus, St. Thomas says, “In our earthly pilgrimage he does not deprive us of his bodily presence; but unites us with himself in this sacrament through the truth of his body and blood” (ST III q. 75 a. 1). The “why” of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist is that the Lord of creation desires to be in friendship with his creatures in the most intimate way possible. And this “why” is something we cannot grasp because it is ultimately the mystery of the love that is God, the love of Father, Son, and Spirit shared with the world, the love that gives us our beginning, the love that loves us to the end. This “why” is something we cannot grasp, in part because it seems too good to be true. We cannot grasp it, but in faith we say “yes” to it.

If we are to give the world a reason to trust in the words “this is my body . . . this is my blood,” if we are to give the world a reason to say “yes” to them, if we are to have a Eucharistic revival, then we must sing better songs, we must look more redeemed, we must live our lives as if these words are true, which means that we must live our lives as if we are truly God’s friends, those with whom God is present, those whom Christ loved to the end. If we are to give the world a reason to trust, it is not enough for us to appear more trustworthy (though that is no small thing). We must manifestly appear to be people who trust in the love that has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit.

We grow in this trust in part through living our daily lives: through ordinary and extraordinary acts of kindness, through openness and generosity to others, particularly those we might find difficult to love, through sacrifice and charity and mercy, through living our lives in ways that would be absurd if we were not truly called by Christ into friendship with God. But we also grow in this trust through moments when we push pause on our daily lives and take time to simply be in the presence of the Eucharistic Lord, to contemplate the love that is present to us under the signs of bread and wine, the love that loves his own in the world and that loves them to the end. We grow in this trust as we contemplate his hidden sacramental presence, as we discern the mystery displayed before us, a mystery of presence that focuses for us all the other ways in which Christ is hiddenly present in our lives: in the hungry to whom we give food, in the thirsty to whom we give drink, in the stranger whom we welcome, in the naked whom we clothe, in the sick person whom we care for, in the prisoner whom we visit. In contemplating this mystery, let us become what we behold: the body of Christ, given for the life of the world.

Trust is contagious. Only those who trust can engender trust in others. That this could be seems impossible, seems incredible. But if the Gospel is true, if Jesus Christ is God, where is the difficulty?