The last Christian celebration to take place in the majestic Hagia Sophia was on May 28, 1453. Ottoman armies camped outside the walls, and Ottoman ships waited in the harbor. The emperor Constantine XI himself prayed for divine protection together with leaders of both the Greek and Latin churches inside the ancient sanctuary. The protection did not come.

The next day the Jannissaries, Christian slaves turned into elite Muslim warriors, led the assault against the city. According to most accounts Constantine threw himself into the battle and was killed, as the much larger Turkish force invaded the city. The small, remaining Christian population in the city fled in terror towards the Hagia Sophia, the church that had stood at the center of the city’s life since the emperor Justinian had overseen its construction in the 530s. Those who remained in the Church were led away in slavery. Massacres and abductions of Constantinople’s Christians followed for the next three days until the Turkish leader, Mehmed (“Muhammad”) II, ordered an end to the killing and enslaving. The Hagia Sophia, along with a number of other churches, was quickly turned into a mosque. Its mosaics were destroyed or plastered over (as no figural images are allowed inside a mosque) and Islamic features (including a pulpit and a prayer niche) were added.

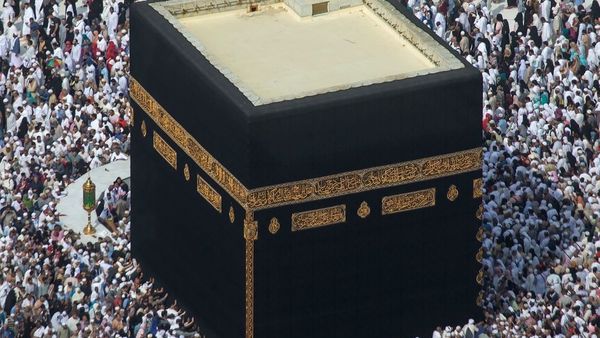

The Hagia Sophia was not just any church. It signified the glory of the Byzantine Empire, and, more importantly, the glory of Christ (the “Wisdom” or Sophia of God) to whom it was dedicated. For centuries it was the largest Church in the world and to many, the most beautiful. When Justinian completed the building he is remembered as saying: “I have outdone you, Solomon!” This was the new Temple, the center of a Christian empire.

There was a lot of brutality, conquest, and slavery in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, and the conquest of Constantinople was only one chapter of this bloody saga. Nevertheless it is the sort of thing most leaders are not fully comfortable with today. The legacy of the Spanish conquistadors, or the Americans who spread westwards and destroyed indigenous civilizations, is sharply criticized in public discourse and questioned in public school textbooks. For Recep Tayyip Erdogan, president of Turkey, there is nothing to question, let alone criticize, in the legacy of the Ottoman conquests.

On March 31, 2018 Erdogan recited the first Sura of the Qur’an in the Hagia Sophia, explaining that his prayer was for the “souls of all who left us this work as inheritance, especially Istanbul's conqueror.” After the announcement for the change of the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque on July 10 Erdogan gave a long speech in which he declared: “The conquest of Istanbul and the conversion of the Hagia Sophia into a mosque are among the most glorious chapters of Turkish history.”

Reading these words reminded me of my visit to Istanbul in the late 1990’s. My flight onwards to Damascus had been cancelled and I was put up in hotel along with a large family of Syrian Americans. The next day we all took a tour of the city. At one point, as we gazed on the Hagia Sophia, a mother told her children: “It was Muhammad the conquerer who took this city from the Christians. He is a great hero of Islam.” She is not alone in feeling this way. The conquests of Islam are often celebrated in the Islamic world. Sometimes, especially with the conquests of the first caliphs, they are seen as signs of divine blessing, proofs that Islam is the true religion.

Yet the story behind the conversion of the Hagia Sophia into a mosque is not only about Islamic triumphalism. It is also about Turkish politics. Erdogan has suffered some electoral defeats in recent years, and by all accounts turning the Hagia Sophia into a mosque was a widely popular decision in Turkey (one early June poll, albeit administered by a pro-government newspaper, reported that 73% of Turks supported the decision). It also reflects Erdogan’s ambitions to be seen as a leader of Muslims globally. One might remember that the caliph resided in Istanbul until Kemal Ataturk abolished the office in March 1924.

Intriguingly, in a pamphlet distributed by Erdogan’s office soon after the July 10 decision to convert the Hagia Sophia into a mosque told two stories in two different versions. The English version begins: “Hagia Sophia’s doors will be, as is the case with all our mosques, wide open to all, whether they be foreign or local, Muslim or non-Muslim.” The Arabic version begins: “The revival of Hagia Sophia is a foretelling of the return of freedom to the Aqsa mosque [in Jerusalem].” A bit further down the English reads: “To what purpose Hagia Sophia will be utilized is a matter of Turkey’s sovereign rights.” The corresponding Arabic text reads: “The revival of Hagia Sophia is a greeting of peace sent out from the depths of our hearts to all of the cities which represent our culture, beginning with Bukhara, all the way to Andalusia.”

This sort of rhetoric is quite different from that of Ataturk, who turned the Hagia Sophia into a museum in 1934. Ataturk, who had led the fight against the allied occupiers of Turkey in the aftermath of World War I, sought to bring Turkey away from its Ottoman past and into a new Turkish future (although he also played role in the cleansing of Christians from Izmir and Pontus).

Yet, finally, is the decision to turn the Hagia Sophia into a mosque an obstacle to interreligious relations? Pope Benedict visited the Hagia Sophia in 2006. Pope Francis visited the Hagia Sophia in 2014. Why could the next pope not visit the Hagia Sophia in its new form? Both Benedict and Francis also visited the Blue Mosque (and both paused there for spontaneous prayer) in Istanbul. Perhaps the next pope will pray instead in the Hagia Sophia with a Muslim colleague.

In a reflection after the angelus prayer on July 13 Francis said the following (after commenting on the “International Day of the Sea”): “And the sea carries me a little farther away in my thoughts: to Istanbul. I think of Saint Sophia, and I am very saddened.” Francis is very close to the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew, and one wonders if his thoughts turned towards the patriarch, and towards Orthodox believers around the world for whom the Hagia Sophia has a special value. Bartholomew himself had said just before the decision in a sermon that the Hagia Sophia’s status as a museum makes it “the symbolic place of encounter, dialogue, solidarity and mutual understanding between Christianity and Islam.”

One cannot help to share in his sentiment regarding the symbolism of the Hagia Sophia. As a museum it had the potential to turn a legacy of conquest into a legacy of bridge-building. And so I join in the sadness of Pope Francis. Yet, the Hagia Sophia also has potential as a mosque.

It is impressive to observe the commitment of Muslims who prostrate before God in their daily prayers. The Hagia Sophia will again become a place of prostration (the literal meaning of masjid, “mosque,” in Arabic). Beautifully, Muslims will prostrate under the gaze of the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose image (at least, according to the announcement of the Turkish government), will not be removed or covered from the back of the apse, but simply dimmed out by a special lighting system.

Some have called for the Hagia Sophia to become a dual ritual sanctuary, where Christians too could also celebrate their liturgy (indeed there are many sites, including the Great Umayyad mosque in Damascus, once the Basilica of John the Baptist, where this took place in the early Islamic Empire). This would be a still more courageous, and wise, decision. There are no shortage of mosques in Istanbul (by most counts there are well over 3000) and no compelling reason why part of the building, at least, could not be a Christian chapel. Frankly, however, this is not a realistic possibility as long as Erdogan is in power.

The Church then should now look with admiration at the faith and piety of the Muslims who will fill Hagia Sophia for prayer beginning on Friday, July 24. The Catholic Church is clear (Lumen Gentium §16) that Muslims and Christians worship the same God. Believers then should remember that when Muslims announce Allahu akbar (“God is greater!”) in the call to prayer that will sound from the loudspeakers now set up all around the Hagia Sophia, they are speaking of the one, true God, our creator and Lord.