In April of 2019, a young African woman named Jamillah walked up to the border station at El Paso, Texas to petition for asylum. Brutal persecution in her home country had forced this young mother to flee for her life and her family’s protection, leaving behind two small children, one a baby only a few months old. But the new “metering” program had been in effect since the previous fall. Agents at the border assigned her a number and told her to come back when it was called. She was left on her own in Juárez, Mexico—homeless and unprotected in one of the most dangerous cities in the world, which saw 1,500 homicides in 2019 alone, and where kidnappings and murders routinely occur in broad daylight.

+

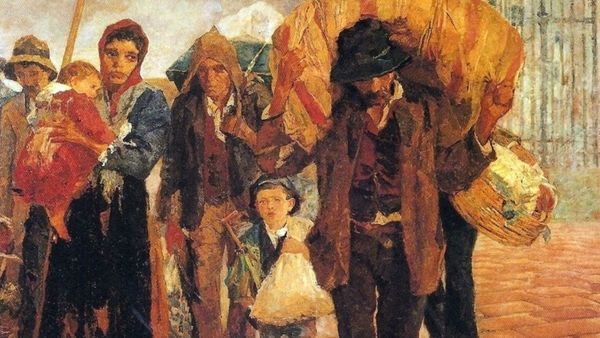

Catholic Social Teaching is especially attentive to the plight of those who have been driven from their homes by persecution. The refugee and asylum seeker bear the likeness of the Holy Family, who fled Herod’s wrath to become strangers in the land of Egypt. Yet, curiously among ordinary pro-life Catholics, attempts to argue for the serious moral significance of immigration policy often meet awkward silence, if not downright suspicion. One reason lies in the strange ways that American political platforms partition the territory. When immigration and abortion become “competing issues” in the voting booth, as in the last few election cycles, it is easy to begin believing that they are somehow really in competition—as though caring about one requires downplaying the other.

Another reason lies in the difficulty of imagining the real effects of abstract immigration policies. Just as it is easy to pretend that abortion is “just ending a pregnancy” without seeing an image of the dismembered tiny human, it is easy to pretend that our country’s treatment of asylum seekers is “just border enforcement” without concretely witnessing the process from the inside.

But a third reason—the one I want to examine in detail here—comes from using a faulty tool of moral reasoning to downplay the moral significance of immigration policy. I mean the distinction between intrinsic evils and prudential matters, which continually sprouts like mold across Catholic social media. This distinction inspires arguments like the following: Immigration policy is a prudential matter on which reasonable people can disagree, in contrast to intrinsic evils such as abortion, which are always wrong. Prudential matters cannot be compared to intrinsic evils. So when calculating the goods and evils to be expected from a politician, immigration policy can be dismissed. For nothing in a “prudential” realm would ever be able to weigh upon the scales when the boulder of an intrinsic evil (e.g., abortion) is on the other side.

This distinction—let us call it the “intrinsic/prudential distinction”—certainly has a traditional “look and feel” in its terminology. But it is seriously flawed. It not only fosters confusion about the nature of moral evil, but also commits its defenders unwittingly to a relativistic conception of prudence.

My aim, writing specifically to fellow pro-life Catholics, is to show why we must scrap the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction, and to offer in its place some better-quality tools of moral reasoning from Thomas Aquinas. I will lay out a program for using these Thomistic tools to evaluate immigration policies, and suggest why pro-lifers should have a special affinity to the cause of protecting this vulnerable population.

Intrinsic Evils vs. Prudential Matters

What is the distinction between intrinsic evils and prudential matters supposed to capture? Consider some examples. Here is one from a popular sermon from 2018:

[In prudential matters] there are many possible solutions . . . and so there can be reasonable discussion and debate among Catholics as to how to best approach and solve them . . . Issues involving prudential judgement are not morally equivalent to issues involving intrinsic evil—no matter how right a certain candidate, on any of these issues of prudential judgement may be.

And from the “Moral Principles for Catholic Voters” by the Bishops of Kansas:

In some moral matters the use of reason allows for a legitimate diversity in our prudential judgments. Catholic voters may differ, for example, on what constitutes the best immigration policy, how to provide universal health care, or affordable housing. . . . The morality of such questions lies not in what is done (the moral object), but in the motive and circumstances. Therefore, because these prudential judgments do not involve a direct choice of something evil and take into consideration various goods, it is possible for Catholic voters to arrive at different, even opposing judgments.

Notice first of all that the distinction is associated with the possibility of legitimate disagreement—i.e. whether two people can legitimately hold opposing views about whether some action is moral. Prudential matters are up for debate. Intrinsic evils are not. Second, the distinction is supposed to capture different categories of evil. Intrinsic evils are necessarily evil in their type. In prudential matters, actions can only be evil, if at all, from motive and/or circumstances.

For example: There is nothing intrinsically wrong with playing the piano, even at one in the morning. But it is (prudentially) wrong to play Shostakovich at one in the morning while the upstairs neighbor is trying to sleep. Murdering the neighbor, in contrast, is always wrong, no matter the time, place, or provocation. Again: reasonable people can disagree about whether I ought to have respected the neighbor’s sleep schedule, or whether it is my right to play my own piano at any time of my own choosing. But reasonable people must all agree that murdering the neighbor would really be going too far. So far all of this sounds plausible. But let us take a closer look.

The Intrinsic/Prudential Distinction: Moral Relativism for Moral Realists?

We should start by unpacking the idea of legitimate moral disagreement embedded in the “intrinsic/prudential distinction.” The idea is this. For some actions, there is no room for disagreement; anyone who tries to justify murder is just wrong. For another set of actions, reasonable people can disagree about what is right or wrong. Sally asserts that the cap on number of refugees resettled in the United States each year is too low, and Molly asserts that it is too high. Neither is able to change the other’s mind, but both have good reasons for their view. This dichotomy between domains of illegitimate and legitimate disagreement may sound vaguely familiar. Where might we have heard it before?

I would suggest that it is effectively a version of the popular “fact vs. opinion” or “objective vs. subjective” distinction. These distinctions always come up in discussing moral realism and relativism in my first-year philosophy class. My students have usually learned to call something a “fact,” or label it “objective,” when disagreements can be resolved by observation, resulting in definitively true-or-false statements. (Facts: The University of Notre Dame is in the state of Indiana. The moon has an effect on the tides.)

In contrast, they have learned to call something “an opinion,” or label it “subjective,” when disagreements seem irresolvable. Moral judgments are almost always labeled “opinions,” along with preferences and predictions. (Opinions: Stealing from the rich is wrong. Chocolate is better than vanilla. This stock will grow 30% in the next year.)

The “intrinsic/prudential” distinction, I would argue, is nothing more than the fact/opinion distinction applied within the realm of morality. It makes room for a handful of “moral facts” about which one could be correct or mistaken, e.g., that murder is wrong. Everything else is left in the “prudential” realm, where disagreements cannot definitively be resolved, and thus reasonable people can disagree—exactly what my students call “subjective opinion,” or the domain of moral relativism.[1]

One way of illuminating the connection to moral relativism is to ask whether prudential judgments are responsible to a “fact of the matter” or not. When there is a “fact of the matter”—or objective reality—and two people make contradictory statements about it, one person is right, and the other is wrong. Consider:

- Ottawa is the capital of Canada.

- Ottawa is not the capital of Canada.

If there is a fact of the matter about Canada’s political organization, then these statements cannot both be true at the same time. One reflects the reality of Canada’s political organization; the other does not.

Similarly, for any moral judgment we can ask whether there is a “fact of the matter” to which that judgment is responsible. The defender of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction surely allows that some moral judgments are responsible to the facts of the matter: namely, those concerning intrinsic evils. E.g.:

- Murder is always wrong.

- Murder is not always wrong.

These cannot both be true at the same time if there is a fact of the matter about the morality of murder. One of these statements reflects the true nature of murder, and the other does not. When people disagree here, someone is right, and someone is wrong.

But according to the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction, when making moral judgments about “prudential matters,” reasonable people allegedly can disagree. Why? What is different about moral judgments in these two different categories? The obvious answer would be that there is no fact of the matter to which prudential judgments are responsible. And that is just moral relativism.

Now, surely most proponents of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction would emphatically deny being closet relativists. However, statements have implications and carry theoretical commitments alongside, whether one wants them or not. Can one say the things that the distinction says, without accidentally committing to a morally relativistic “prudential” universe? Easier said than done. The defender of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction owes us some some explanation of why disagreement is acceptable for this set of moral judgments but not others. But any explanation will end up either (a) accidentally destabilizing the entire “intrinsic/prudential” distinction itself; or (b) accidentally decoupling prudential matters from objective moral reality.

Can Prudential Matters Be Tethered to Moral Reality?

Take Molly and Sally’s allegedly “prudential” disagreement described above:

- “National security considerations morally justify lowering the refugee cap.” (= “Lowering the refugee cap is morally good.”)

- “National security considerations do not morally justify lowering the refugee cap.” (= “Lowering the refugee cap is morally evil.”)

Obviously, these two statements contradict each other. Now to avoid moral relativism in this arena, the defender of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction will have to hold that one of those two actions—lowering the refugee cap or maintaining it—is objectively morally wrong. In other words, there will have to be some fact of the matter about whether resettling fewer refugees is morally justified, so that one statement is true, and the other false. But then: Why would it nevertheless be legitimate for “reasonable people” to hold conflicting views on the matter?

(1) One possible explanation is that the slogan, “Reasonable people can disagree,” is simply a peacekeeping strategy. Even though one statement about the refugee cap is false, it is difficult to convince its champion that she is wrong. To avoid endless disputes, Sally and Molly agree to disagree, each graciously designating the other position as “reasonable,” acknowledging that the other person thought hard about her view and truly believes in it. In other words, they tolerate disagreement in order to coexist peacefully in society together.

Suppose, then, that the breakdown of argument is what makes it “OK to disagree.” But disagreements about intrinsic evils, like physician-assisted suicide, can be just as endlessly entrenched. So then it will be “ok to disagree” about intrinsic evils too, and the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction collapses in on itself.

(2) Another possible explanation is that disagreement is acceptable in the “prudential” arena because evils in that arena are a different, lesser type of evil from “intrinsic evils.” In matters of intrinsic evil, disagreement cannot be tolerated because the evil is just too severe. In prudential matters, the stakes for getting it right are small, and disagreement can be tolerated.

But once the distinction’s defender allows that objective moral evils can be committed within “prudential matters,” then it is already all over. The whole point of the distinction, in political discussions among Catholics, was to insulate entire categories of law and policy in advance as morally “lightweight,” so that they need not count when adding up the evils to be expected from a given politician. But as soon as the distinction’s defender grants that the policy categories marked “prudential” have real, objective moral contents, then he can no longer allow himself to set them aside in advance. He will have to lift the lid of the saucepan after all, and judge whether its contents are wholesome or poisonous.

In short: once “prudential judgments” are made responsible to an objective moral reality, the intrinsic/prudential distinction as a tool for drawing a sharp line between issues that “count” and those that do not promptly collapses. But can’t we still distinguish between acts that are “evil in themselves” vs. acts that are “evil only due to the motive and circumstances”? Not if we understand moral evil correctly; more on this later.

Insulating Prudential Judgment from Objective Moral Reality

One can save the intrinsic/prudential distinction, however, by embracing moral relativism in prudential matters, and arguing instead that there is no right answer to prudential questions. In a popular formulation, “Prudential judgments are rarely black and white.” On this solution, “reasonable people can disagree” on the morality of lowering the refugee cap, but not on the morality of murder and the capital of Canada, because there is just no objective fact of the matter about what would count as a justifiable lowering of the refugee cap. For Sally, national security considerations do not justify a lower cap, because that is the view she worked out for herself. But for Molly, they do justify a lower cap: That is the view that she worked out for herself. Each speaker’s view is true for her, as an expression of her considered opinion, not as an expression of moral reality. This is standard moral relativism applied to prudential matters. “Not black and white” is exactly how my students describe “opinion.”

Now the defender of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction might still try to escape moral relativism here by suggesting that although one of the positions on the refugee cap is in fact objectively true, no one can know for sure which it is. Hence Sally and Molly are each entitled to their opposing views. But this is just moral relativism in a different disguise. If the moral truth of the matter is inaccessible to us, then we are effectively decoupled from objective moral reality. Our judgments about the refugee cap are still not answerable to moral reality; they merely express a personal opinion reached after making a “good faith effort.” An evaluation of personal effort replaces the evaluation of the truth of the moral claim.

Alternatively, one might try to escape by restricting “prudential matters” only to choices between two equally good policies, such that there is no fact of the matter as to which is better. But if that were true, then she would have to admit that her favorite “prudential” policies are as equally, indiscernably good as the competing policies of her opponents. Of course, nobody believes such a thing: The whole point of disagreeing is that both parties sincerely believe that their policies are the better policies! Otherwise, reasonable people certainly ought not to disagree: They are clogging the pursuit of the common good with useless debates with no moral significance.[2]

As a last recourse, then, one might object that the “relativism” labeling is offensive. Prudential judgments about the refugee cap are arrived at by deep reflection, self-education, and consideration of all available information. Surely these are weightier conclusions deserving more respect than the “true-for-you-but-not-for-me” moral relativism of the masses! But the only difference is packaging. Flippant or carefully-considered, the underlying status of the moral judgment remains the same. The only way that two conflicting statements to be legitimately asserted as true at the same time, is if there is no objective fact of the matter, or at least no knowable fact of the matter, about which one is true. Otherwise, one of the statements is in reality false, and someone is in reality wrong.

And if there is no (knowable) objective fact of the matter about which one is true, then that is exactly what the general populace describes as “a subjective opinion.” And a subjective opinion is a subjective opinion, whether reached after six years of workshopping policy statements in a wood-paneled room, or after watching a two-minute YouTube video in a coffee shop. If the goodness or evil of certain actions is not a discoverable fact of the matter, then the requirement to be “of goodwill or “reasonable” is a mere fig leaf. If there is no moral reality in a situation to which we are responsible, then not only reasonable people, but also unreasonable people, can disagree.

A Failed Distinction: Prudential Matters, Individualism, and the Enlightenment

So how did Catholic political discourse get infected by this distinction? I believe the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction has gained such acceptance because it borrows terminology familiar from classical natural law theory or Catholic moral theology. But under the linguistic shroud, it is simply the pale ghost of a widespread individualistic moral theory, in which objective moral “oughts” are viewed as constraints on intellectual and moral freedom that reduce the sovereignty of the individual, and that therefore should be kept to an absolute minimum. Avoid violating that small set of oughts—representing a small, universally-recognized set of especially heinous acts—and then “do what you will.” As long as one is not violating the basic oughts, one’s actions can be shielded from scrutiny, as indicated by the slogan that “reasonable people can disagree.”

It should not be surprising that the intrinsic/prudential “axis” cuts between moral obligation and individual sovereignty. The distinction itself, I believe, is a corruption of a standard theological distinction between moral teachings of the Church that are binding on Catholics[3] vs. those left up to individual consciences.[4] That distinction, however, is a juridical distinction. It is a matter of historical contingency which actions the Church has happened to condemn in such a way as to make the prohibition obligatory. Nobody (I hope) would claim that an action cannot be intrinsically evil unless it appears on that list.

In any case, this individual-sovereignty moral universe is certainly not that of classic natural law theory or Catholic moral theology. It is, rather, patterned after the moral universe of John Locke, where the human being has complete freedom in his own actions as long as he does not violate a minimalist “law of nature” rooted in a basic human right to life, or the laws of the state to which he has ceded some of his freedom in exchange for protection.[5] It has, curiously, exactly the same structure as the moral theory that Judith Jarvis Thompson endorses in her 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion,” where she delineates a narrow realm of binding obligations that define what is just, outside of which realm all other actions can be ranked as more or less nice.

A proponent of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction may want very much to avoid inhabiting such a moral universe. But the distinction is what it is, and will inexorably vacuum him back into it as he tries to escape.

Every Evil Action Is Intrinsically Evil

So are there alternative tools we can use to analyze the good and evil of an action? Let us see if Thomas Aquinas can help. Aquinas does have a notion of intrinsic evil and a notion of prudence. But they govern one and the same realm of human action: All evil actions are intrinsically evil (and all good actions are intrinsically good), and prudence governs all human actions, not just a certain subset.

Let me explain. For Aquinas, once an action is recognized as being of an evil type, such as murder, no additional information about the situation can “undo” that fact. No matter how good your intended goal was (to save your own life), or how many good effects there may be (you will also inherit a lot of money which you will give to the poor), or circumstances that make the act less evil than it might have otherwise been (the murder is painless and concealed from everyone whom it might distress)—none of that further information can change the type of action back to “good” from “evil.”

This all sounds close enough to the notion of “intrinsic evil” described earlier. But now for the key difference: For Aquinas, every evil action is intrinsically evil. There is no way for an action to be morally wrong at all, except by belonging to an intrinsically evil type of action. Aquinas divides up actions into good and evil “moral species,” just as he divides up animals into different species.[6] There is no way for Fido to be an animal without belonging to some animal species such as “dog” or “elephant.” Similarly, there is no way for an action to be evil without belonging to some evil species, i.e., a type of action whose definition includes an opposition to the human good.

Evil types of actions include, e.g., impatience, pride, murder, lust, theft, selfishness, envy, and gluttony. Each of these types is intrinsically opposed to the human good. There is no right way to be gluttonous, just as there is no right way to murder. This means that Aquinas would reject the claim we saw in connection with the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction, i.e., that some actions are wrong in their type, while others are good in their type and wrong only due to some detail of the particular situation (“motive or circumstance”). For example, the intrinsic/prudential distinction claims that murder is fundamentally different from eating too much pie: Murder is an intrinsically evil type of action, whereas eating pie is a good type of action which only becomes wrong because in the circumstances I happened to eat “too much” of it. For Aquinas, in contrast, the pie-eater is deluding herself. The “too much” automatically transforms my action from an innocent pie-pursuit into an act of gluttony—an intrinsically evil type of action. I am simply patting myself on the back, pretending that my act was mostly good with the tiny flaw of “too much.”

Indeed, it is always some detail of the situation that determines whether the action’s type will be evil.[7] In every murder, there is always some detail of the situation that transformed an act that could otherwise have been described neutrally (e.g., as “putting a knife into someone’s chest”) into an act of murder. So the label “intrinsic evil” is redundant. We can just speak of “evils” from now on, knowing that any action that is evil is so because that type of action is intrinsically opposed to the human good. Of course, some kinds of opposition to the human good are more “grave” (morally damaging to the agent) than others. Murder, for instance, is worse as a type of action than gluttony (for reasons we cannot get into here). But all evil actions belong to an intrinsically evil type.

Prudence Governs All Human Actions

If every evil action is (intrinsically) evil, what is the role for prudence? Aquinas insists that prudence is required in every single human action, because this virtue is what helps us to identify the morally relevant details of a proposed action: “Prudence applies universal principles to the particular conclusions of practical matters.”[8]

Humans are rational creatures whose “good” (i.e. what completes/fulfills us) is highly complex. So, Aquinas explains, it is impossible to spell out in advance some specific means that every human must take for achieving the human good. Instead, we must evaluate the right course of action for each situation in which we act. That’s where prudence comes in.

Now every human action is a particular action in some particular context. There is no such thing as an “act in general”; there are only particular acts belonging to some specific moral type, such as gluttony, patience, self-sacrifice, or sacrilege. (Similarly, there is no such thing as an “animal in general”; there are only crested cranes, polar bears, and brown recluse spiders: particular animals belonging to specific animal kinds.)

Thus prudence cannot get a complete picture of “what I am doing” if I only consider my action in an abstract, highly generic way. In fact, describing actions too generically is dangerous because the more generically an action is described, the more likely it is to look good. At the most general level, any action can be described as “doing something to achieve some human good” (that is why Aquinas says that we only ever act for the sake of something good). In a sense, actions begin as good in the abstract and are corrupted in the particular. As we get further down toward the specifics of the particular situation, the more risk there is that the action will be “corrupted” by one of the relevant details and end up “defecting” to an evil class.

For example: The pleasure of taste is good for the human being. Thus “seeking a pleasurable taste” is a good kind of action in itself (not morally neutral as some might assume). If I add the detail of “pie,” nothing about the action-type changes. If I add more details like “in my kitchen, in the middle of the night, because I was too hungry to sleep,” still nothing changes. But if I add the detail “immoderately,” i.e., an unreasonable amount—now I have added an opposition to reason, and the kind of action I am performing changes from a good species (seeking taste-pleasures) to a bad one (gluttony). Aquinas adds that an action can belong to more than one type: If the pie also turns out to be Bob’s, now the pie-eating is additionally theft.

The same applies to murder, though in murder cases we are not usually tempted to redescribe the situation at a too-general, misleadingly benevolent level. Suppose that I tell you I am planning to “do something to earn my living” (surely a good action!). Then I tell you that the “something” is “cutting into human bodies.” Still, you do not have enough information to know whether this detail changes my action-type. Do I plan to be a surgeon, or a hired assassin, or an executioner, or a coroner? I will have to add “in a death-dealing way” and “upon innocent living people” before you know I am contemplating murder for hire. (Or in the words of Christopher Walken’s character describing a prank that turns out to be a murder: “I jumped out and pranked him! . . . to death . . . with a tire iron.”[9])

In short: any act looks like a good act, if it is described in a sufficiently general way, as a quest for some human good. The devil is, quite literally, in the details of the particular action undertaken in context. If any of the details of a concretely-proposed, particular action carries an opposition to the human good (what Aquinas calls a “dissonance with reason”[10]), the act “defects” (deficit) or literally “comes undone.” It dissolves into an act of an intrinsically evil kind. Prudence is precisely what helps us recognize such defects in an action we are considering.

At this point, someone might wonder: Is there any room for a “gray area” where “reasonable people can disagree” in Aquinas’s ethics? Largely, the answer is “no”—except when the situation is in itself genuinely morally indeterminate (such that there is no knowable fact of the matter). This could occur when several means are available that are all equally good or equally bad, so that there is no fact of the matter, or at least no knowable fact of the matter, about which is better.

For instance, there is no single exact number of refugees that should be resettled in the US each year (such that 150,000 admissions would be good, and 149,999 admissions wrong), just as there is no single exact number of minutes I should work per day to maintain work-life balance. Rather, there is a kind of range such that (for a certain country, given its current resettlement infrastructure) there is some number that would definitely be too few, and some number that would definitely be too many, and an indeterminate range in between, where anything in that range would be acceptable. Moral indeterminacy does not imply moral relativism, because the statements about what should be done do not contradict each other.

However, this kind of gray area occurs only at a very specific level of analysis, where one is fine-tuning a good act, and not at the much more generic levels of analysis where people generally want to invoke it.

Evaluating the Morality of Immigration Policy

How do we use Aquinas’s “moral tools” to evaluate immigration policy? There is not enough space in this essay to analyze even one policy completely. That can be a project for another time. For now, I just want to drive home the fundamental difference in Aquinas’s approach from what we saw earlier with the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction, and illustrate the kinds of questions that have to be asked concerning any given policy.

Recall that the whole point of the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction was to make a claim about the relative moral weights of abortion and immigration as “issues facing the voter.” In invoking the distinction, much has been made of the fact that immigration policy is a matter of “regulating borders”—an act that is good in itself and open to many proposals concerning how best to do that in practice.

But now with Aquinas’s assistance, we can see right away that apples and oranges are being compared. On the one side of the ledger are acts that have already been described in enough detail to be slotted into a morally evil species (e.g., abortion). On the other side are those that are still described very generically in terms of the quest for some good end (e.g. “how best to manage our borders”). Any act described at such a level of generality will merely be good and open to further specification. Again, the devil is in the details. For Aquinas, we cannot make any comparative remarks until we know concretely what is being done.

To illustrate why, imagine approaching abortion at a similar level of generality: i.e., as a general matter of “promoting women’s health” within the framework of “healthcare policy.” Obviously, promoting women’s health is a goal that is good in itself and open to many proposals about how best to do that in practice. And just as obviously, it would be absurd for someone to claim, on those grounds, that the entire category of “healthcare policy” can be set aside as morally unimportant—without having even looked at the details of any particular actions that are commanded or permitted by specific policies under that header! It is only when we move toward a particular health-promoting situation of a particular woman and a particular doctor, that the detail of “non-therapeutically cutting an unborn human into pieces” comes into view as part of the means chosen to promote this mother’s health. At that moment, prudence recognizes the action-type as something evil: abortion, a sub-species of murder.

But this sort of absurdity is exactly what is being replicated over and over in the quick dismissals of the moral weightiness of “immigration policy.” We need to pry ourselves loose from this uselessly generic level of analysis, where everything appears morally good. Any morally corrosive details can only come into view closer to the level of particular laws, policies, and actions unfolding in concrete situations. Only then can prudence recognize whether some of those actions and policies fall under an evil action-type, and evaluate how grave those evils actually are.

As a result, it should be immediately clear that we need to be much better informed about the concrete details of particular immigration policies and their impacts on real human beings in order to make responsible moral judgments about them. This is no small task, and this essay is long enough already. So I will leave such discussions for another time. In the meantime, though, let me simply note three ways in which pro-life Catholic discourse around immigration will have to change if we toss out the “intrinsic/prudential” distinction and implement more Thomistic tools of moral reasoning.

- We will need a more sophisticated “moral vocabulary” to name the intrinsic evils committed in visiting various kinds of indignities upon innocent human beings. In Aquinas’s taxonomy of good and evil actions, the fifth commandment is the expression of a more basic precept, “A human being should do harm to no one.”[11] But apart from murder, torture, or slavery, we lack names for most kinds of harm, even very serious kinds, that humans may inflict on each other.

Thus we are left with overly clinical descriptions of the harms inflicted by certain immigration policies: e.g., “returning a torture victim to the government that tortured him,” “unnecessarily putting someone’s life at serious risk,” “forcing someone into dangerous or unsanitary living conditions,” “inflicting such-and-such physical or psychological trauma.” The qualifiers (e.g., “separating children from parents without evidence of abuse”) misleadingly reassures us that they are neutral in their type and marred only by circumstance. In reality they are actions irremediably evil in their type, for which we happen to lack a label.

- We will need a better discourse around moral gravity. Pro-life speakers often state, in good Lockean fashion, that the most grievous harm that could be done to a human being is to kill him or her, because all other rights presuppose a right to life. While understandable rhetorically—to address interlocutors who do not take the loss of unborn human lives as especially weighty—nonetheless the claim as it stands is simply false. It is obvious, for instance, that a mercifully swift execution could be less harmful to a victim than daily torture and life imprisonment.

But also, the Catholic tradition has never considered death the worst thing that can happen to us. And I suggest carefully reading Aquinas’s account of the prohibition of murder, which is grounded in the human person’s having “a nature we ought to love,” not in the necessity of life for enjoying other goods.[12] None of this is to downplay the gravity of killing the innocent. The point is just that we cannot assume that every offense against the “nature we ought to love” necessarily pales in comparison.

- We will have to be less quick to use the moral escape hatch of claiming that some evil is merely foreseen but not intended. One reason that immigration-policy-related evils are often downplayed is that we tend to dismiss the harms involved as “unintended side effects” of a praiseworthy enforcement. Children become separated from their parents as a sadly unavoidable effect of “zero tolerance.” Any evils, we reassure ourselves, are inflicted by someone else—the foreign government that tortures or kills the improperly deported asylum seeker, or the gang that kidnaps the asylum seeker sent back to Mexico to await a court date.

In many cases, such attempts to portray the harms as “mere side effects” are simply incorrect. But even where a harm can be correctly identified as a side effect, that is not enough to “sanitize” an act morally, given Aquinas’s conception of moral evil. Going forward, we will have to take a hard, painful look at how omitting to help, tolerating evils unnecessarily, or placing human beings into the path of harm, can also fall into intrinsically evil action-types.

These thoughts require considerably more development and defense; I offer them here only as a programmatic sketch for future discussion. But I hope to have shown that the intrinsic/prudential distinction is a seriously flawed tool of moral reasoning that should be especially abhorrent to pro-life Catholics. It encourages exempting whole areas of law-making, policy-making, and enforcement from the serious moral analysis to which we are in fact obliged as citizens. Moreover, it encourages thinking of the moral life minimalistically in terms of avoiding a small set of absolute evils while leaving few constraints on the large and loose “prudential” sphere. It encourages excusing, rephrasing, and downplaying the serious moral evils perpetrated under the allegedly prudential “immigration” umbrella, in exactly the same way that the serious moral evil of abortion is excused, rephrased, and downplayed under the “healthcare” umbrella.

+

What became of Jamillah? African asylum seekers are especially vulnerable in Mexican border towns. Most obviously, the color of their skin marks them out to predatory gangs as easy targets—but they also face other kinds of special risks. Jamillah was lucky enough to find a place at a shelter overcrowded to twice its capacity. Then her health began to worsen. She was persistently misdiagnosed by local doctors, due to incompetence, the language barrier, and racism. The tuberculosis diagnosis finally came, but too late to save her. On October 1, 2019, she died alone in a hospital in Juárez, Mexico. This essay is dedicated to her.

+

ADDENDUM: Some readers have suggested that my critique of the intrinsic/prudential distinction contradicts CCC §1749-1761, which distinguishes the "object" and "intention" as the morally specifying features of the act, from "circumstances," which merely increase or decrease the gravity of the act. But these passages of the Catechism actually are consistent with the position I ascribe to Aquinas, rather than detracting from it. If a detail of the action-situation is sufficient to place the action into an evil species, then by definition it is not a circumstance. Circumstances, properly speaking, are the remaining details of the situation which are not morally specifying. The Catechism recognizes this point when it says that circumstances merely increase or decrease the gravity of the act. What causes the confusion is that details that are morally specifying in some situations may be mere circumstances in others. "Too much" in the matter of eating cake is morally specifying, causing the act to be "gluttony." But "too much" in the matter of laughing at a joke is not morally specifying; if anything it might make the one laughing look a little ridiculous. That perhaps makes the laughter less perfect than it might have been, but does not change the moral specification of the act and is therefore a true circumstance.

[1] After working this out, I discovered that Meghan Clark observed the morally relativistic tendencies in appeals to “prudential judgment” here; she is the only author I have found doing so.

[2] If someone argues that disagreements concern which policy is practically better, not morally better—it is in Aquinas’s terms morally wrong to choose a practically worse means to the common good. So both options can only be equally morally good if they are also equally practically good.

[3] Those that fall under the Church’s magisterial teaching or for which there exists a traditional consensus among theologians.

[4] For just one example of how the juridical distinction transmogrifies into a general tool of moral reasoning, see “The Major Confusion of Catholic Voters: When a Catholic Can Differ With the Bishops.”

[5] Locke, Second Treatise on Government, ch. 2, sect. 6.

[6] Aquinas, Summa theologiae Ia, q. 18.

[7] In Summa theologiae Ia, q. 18, Aquinas identifies three kinds of details that determine the action’s moral species: Circumstance, intention, and object. The intrinsic/prudential distinction falls prey to a common confusion about this distinction. In distinguishing acts made wrong by a circumstance vs acts made wrong by their type, proponents of the distinction (a) confuse the act’s object with its moral species, and (b) mangle the nature of circumstance, in such a way that Aquinas’s remarks in q. 18 become almost completely unintelligible.

[8] Summa theologiae, IIa-IIae, q. 47, a. 6.

[9] Saturday Night Live, “Prankster Larry,” aired 2/22/2003.

[10] Summa theologiae Ia-IIae, q. 18, a. 10, ad 3.

[11] Summa theologiae Ia-IIae, q. 100, a. 3: “Among the precepts of the Decalogue those precepts are first and [most] common which do not need to be taught except insofar as they are written in natural reason, as though known by themselves, such as “A human being should do harm to no one,” and others of this sort. Aquinas holds that the Decalogue includes other moral precepts that are “corollaries” reducible to each commandment; he provides a kind of shortlist in ST Ia-IIae.100.11: “To the fifth commandment, which concerns the prohibition of homicide, is added the prohibition of hatred and any injury [or: profanation] against one’s neighbor, as in Levit. 19, ‘You shall not stand against the blood of your neighbor’; and even the prohibition of the hatred of one’s brother: “You shall not hate your brother in your heart.”

[12] Summa theologiae IIa-IIae.64.6.