We declare God’s wisdom,

a mystery that has been hidden,

and that God destined for our glory before time began.[1]

I.

Through Word and Spirit, the Father creates and redeems. In making this confession, and in coming to see how it shapes our imagination of all things, Christians find themselves drawn into a universe of speech and imagination where mystery is ever present.

Mystery is present, first, because at the heart of their faith Christians confess that the Word became flesh, that the Word took into his own person flesh and a human soul. This mysterious union of the Word and his flesh is not “explained” by centuries of Christological reflection and definition; rather, that inspired tradition has bequeathed to us terms and carefully honed images that enable us to talk with more clarity about exactly what must remain mysterious to us and why. The union that is Christ is also the foundation for our incorporation into Christ, the foundation for the mystery of salvation. Christians are drawn into the one body of Christ and thus into the communion of the Triune life. About this union we are, again, given much to say and to hymn, but ultimately a divine power is at work that we cannot fathom.

These basic Christological and ecclesiological connections are already apparent in the use of the Greek mysterion in the New Testament. For Paul the mystery that has been revealed in Christ is the plan of the only wise God for the salvation of the world—mystery thus being closely connected to Jewish traditions of the divine wisdom. This mystery is the key to understanding both the direction of history and the inner meaning of the Scriptures. Thus at 1 Cor 13:2, understanding “mysteries” is paralleled with understanding prophecy, and in Rev 1:20 (and 17:5) mysteries about the end are seen by the author and partially understood (cf. 1 Cor 1:51), and preached to the world. But at Eph 5:32 marriage is a mystery concerning Christ and his Church, indicating that the union of Christ and believers is also intrinsic to the mystery of the divine plan. These seeds grew and flowered in early Christian tradition. Thus, for example, in Origen the mystery of Eph. 5:32 becomes the mystery by which the whole body of believers shares in Christ’s passion and death and will rise truly united in him. In the fourth century one finally begins to find mysterion applied to the rite which unites us to the death and resurrection of Christ, the Eucharist.[2]

Second, mystery is present in this imaginative universe because reflecting on the action of the Word in the world is inseparable from considering who is present and thus from reflection on the Father who sends the Son and Spirit. The nature and activity of Father, Son, and Spirit cannot be comprehended by the creaturely mind, however much we are also in the divine image. From eternity the Father generates a Son without dividing himself, giving rise to one who is truly God and yet without giving rise to a second God. The Spirit is a distinct person, and yet is also the Spirit of the Father and the Spirit of Christ. The mystery here is not simply or even primarily because God is eternal and simple—important and beyond our experience though these truths are—but because God’s existence is a communion established by the Father’s eternal loving gift and eternally through the return of that love. This is a personal action, an action of love in eternity, one that in eternity results in communion and yet never division. The analogical resources that we human beings have to imagine such a thing can only point us towards such a life and force on us a straining to comprehend what remains beyond us.

When we see this second reason that mystery is interwoven with the Christian imagination, it becomes clear that a study only of the development of mysterion (and the Latin sacramentum or mysterium) is insufficient for us to understand Christian discourse on mystery. That discourse is shaped also by the Christian tradition of reflection on divine transcendence, and on what it means to be a creature looking toward the Creator.

And so, third, the centrality of mystery in the Christian universe flows from the fact that the creation is created and sustained by the Trinitarian life as the sea in which our imaginations swim, as the context within which we enter into a process of reflecting on ways in which the created order in its forms, movements, beauty, and order reveals to us the love, transcendence, and mystery of their Creator. This moving composite of signs, the creation, has become, however, so often difficult for us to read; the dark mysteries of our fallenness occlude our ability to swim well in what should be a sea of signs.

I have already noted that the foundational Christological dimension of mystery extends from the person of Christ to the union of believers in Christ and thus to the Eucharist as a sacramental sign and reality. I must return to that point here and note that at the very heart of the creation are the Church’s sacraments, signs that incorporate us into the mystery of Christ’s person and the Triune life. Participation in these signs is, in part, an education for the Christian imagination, so that we may look at and see the world as it is and should be. In other words, Christian liturgical speech and movement exists as a sign to and of what it means to be created, of existence in the presence of mystery. The theme of mystery, then, is interwoven with the doctrine of creation and with our vision of what it means to be human.

Thus, mystery is not something Christians should consider primarily an attribute of terms or statements that defy our understanding; mystery is primarily an attribute of the divine being and life. Mystery certainly does attend upon terms and statements about that divine mystery, and not understanding what follows from that for our speech will greatly hamper the Christian thinker. But a true appreciation for mystery in Christian imagination and discourse flows from recognition that mystery is primarily an attribute of the Holy Trinity, and from recognition that a Christian account of mystery is interwoven with an account of the created order’s relationship to that transcendent divine life.[3]

II.

But for the moment let us retreat from talking directly of the mystery of God and speak about the mystery attendant upon Christian speech and statement. One of the best explorations of this topic is to be found in the work of Matthias Scheeben, the mighty German theologian of the mid-nineteenth century. Scheeben first published his Die Mysterien des Christentums (The Mysteries of Christianity) in 1865 when he was only 30, but this was the work that he was revising at his death in 1887, and we have available an edition from 1941 which takes account of Scheeben’s own notes towards revision. Scheeben’s text orders the whole of Christian theology around the concept of “the mysteries,” in part because Scheeben seeks to oppose those trends in early nineteenth Catholic theology that saw Christianity as an enterprise consisting in rational reflection on irresistible evidence. Against such a claim Scheeben offers a Thomism deeply shaped by his engagement with Patristic theology.[4]

For Scheeben, that which is mysterious fascinates us and draws us in; it is not simply the obscure, but that which stimulates in us a dawning awareness of a new world. In opening our eyes to mystery, we recognize that a gift has been given. We recognize that in revelation God has enabled us, as a light beginning to break through darkness, to see what previously was hidden from us. “Mystery,” understood as “something which cannot be perfectly comprehended,” is a common feature of our natural existence. But, even in the natural world, some mysteries of this kind may be revealed and yet are still in a certain sense obscure; we cannot form a clear idea of them because they fall outside our experience. Scheeben gives the example of light explained to one who has been blind from birth, or even a distant foreign country explained to one who has never traveled. Such mysteries may only be conceived and understood by means of faint analogies with things that we do know.

The Christian mysteries are analogous to these secular parallels—mysteries communicated by revelation and understood only by faint analogy, mysteries that open our eyes to a new world we may only dimly see through the dense fog of created and fallen existence. God thus speaks within the created order in ways that call us to belief, and the act of believing is both a breaking open of the imagination, and a call to ascend toward the mysteries revealed in such words. His conception of mystery thus involves elements of a theology of divine being, of revelation, of creation, and of sacramental and spiritual theology.[5]

One of the most important features of Scheeben’s account is that he speaks of us learning to recognize the theological mysteries as gifts, and hence as encouraging thankfulness for them and wonder at them. This emphasis on what we might term the spiritual phenomenology of how we should approach the mysteries of Christian faith is a consistent feature of his reflections on how we should think towards God. At the end of his book Scheeben reflects on the interwoven nature of faith and reason, defending theology as a rational enterprise, but showing how the exercise of rationality must find itself shaped by faith, both in the sense that we must pray for faith that God has spoken of realities that could not otherwise be known, and for faith in the gift of grace without which these mysteries cannot be spoken of well.

Theology is, Scheeben writes, a scientia sapida, a science full of delights, because it deals with God and hence with the goal of the human being. Because the study of it may lead us to see harmonic relationships between the mysteries, we are delighted and drawn on to further study; and as it thus moves to aim at the divine being, the highest principle, it is also wisdom. But theology always also stems from and proceeds via the humanity of Christ, the incarnate wisdom—“the weakness attending our earthly nature continues to cling to our theological wisdom, as the infirmity of the flesh clung to the earthly Christ.”[6] For Scheeben, the propositions and speech gifted us in revelation act as the occasion for the human intellect and imagination to ascend towards the Creator and to see the world anew. In this ascent the defeat of the human intellect before the mystery of God is a gift, not a problem to be circumvented.

III.

To Scheeben’s perspective we may add one of the most famous discussions of mystery in the twentieth century, offered by the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel. Marcel contrasts problem and mystery—the former as both something to be solved, and something that we encounter as a reality at a distance from ourselves, and the latter as something which both transcends all techniques that we might bring to bear in the hopes of solving it, and which we encounter as related to the depths of our being. To give human analogies, the mysteries of birth and death are not solvable, they must be lived with, they are a presence that should be encountered (for Marcel) through our disponibilité, our openness to love and communion.[7] Marcel abandoned his agnosticism for Catholicism at the age of 40, but remained suspicious of all philosophical attempts to prove the existence of God, preferring to emphasize the movement towards mystery that he felt to be an intrinsic feature of human existence whose recovery could best pave the way for a modern revival of the religious imagination.

Marcel supplements Scheeben’s extensive reflection on the consequences for theological reasoning of our recognition that mystery does not simply retreat as we increase in knowledge. The recognition of divine mystery calls from us an openness and attentiveness, and a recognition that there are patterns of life within which that openness may be nurtured. Marcel’s vision of mystery encourages us to reflect not only on the permanence of the mystery in the face of our ascent towards it, but also on the link between recognition of the mysterious and the call to a life of love for the other and for the world in which mystery is present. This call is, however, no nebulous call for “openness”; it is a call for a formed attention to the presence of mystery, the forerunner of Marcel’s mature Catholic life in which attention to the mysterious is formed by the life of faith and draws us slowly into awareness of a new world.

Olivier Clément, the French Orthodox theologian, wrote that for Vladimir Lossky “a dogma is not an attempt to explain the mystery, or even an attempt to make it more comprehensible. Rather, it seeks to encircle the ineffable and to compel the mind to surpass itself by a clear-minded sense of wonder and adoration.”[8] This statement is not a denigration of the intellectual (that would be surprising in a theologian so adamant about such questions as the filioque), but a gnomic statement of the role of dogmas given to the Church in relationship to the mystery of God. A dogma encircles an aspect of the mystery to draw the mind more clearly to an appropriate wonder at the mystery as a whole. Lossky devotes little time to discussing dogmas as propositional statements—although he assumes that they are, and as such a gift for the intellect—because his fundamental concern is to celebrate dogmas as enabling the Christian to share in the life of the God who reveals himself in Christ. In describing this sharing Lossky also maintains the primacy of the apophatic, that growth in awareness of the divine mystery is always growth in awareness and wonder at the transcendence and incomprehensibility of God.[9]

That we should come as little children (Matt 18:3) has many applications, and some speak directly to the theologian. The small child who wonders if the dappled light on the river might be fairies has a real gift that is lost to the adult who knows too easily what light on rivers may and may not be. Of course, growth towards rational investigation of reality is a good thing, but wonder is misunderstood when it is only viewed as a romantic naiveté dispelled by education; wonder is also a form of attention that may accompany the maturity of developed rationality. Indeed, I would suggest that wonder and attention to mystery is something that the theologian should seek far more consciously to train in him or herself and in others.

IV.

And thus we must ask, how are we trained for wonder, or trained to wait for wonder to dawn upon us, to be given us? Fundamental, I suggest, is reflecting on the winding nature of the path by which we ascend into greater awareness of the divine mystery. This path is one of confession and repetition, one in which wisdom grows as one comes to recognize the necessity of speech and image that can shape the human imagination, and that such speech and image (whether natural or revealed) is a gift. The speech and image of which I speak includes the gift of Scripture, the liturgy, the lives of the saints raised up for us, the traditions of artistic representation fruitfully taken up by the Church. But it does not include only this for, even if we do not see it as we should, the beauty and order of the world already suggests its role as a semiotic order pointing us on toward its Creator and, in the light of the gifts mentioned in the previous paragraph, a new seeing of the world as the product of the Creator gradually may dawn upon us. And thus, to speak about our training for wonder we must speak about the very character of the created order into which God has revealed himself.

The best way for me to sketch my argument here is to turn back to the roots of Christian reflection on mystery in both East and West, back to Maximus the Confessor and Dionysius the Areopagite. Plato aptly noted that creation is a moving image of eternity. This is a theme adapted and deepened in Christian tradition—in one direction by reflecting on the difficulty the fallen mind has in discerning where and where not the creation is an image, and in another by faith that God has revealed to us a language and action that may enable our growth in understanding how this world and its activities may image eternity. Maximus the Confessor’s famous reflection on the symbolism of the liturgy offers an excellent example of how Christians transformed this tradition.

For Maximus all things are from and sustained in harmony by the power of the one transcendent Creator. Seen truly, the individual relationships between things reveal the most important relationship, that all are united together by and to the one sustaining cause and power: “when the mind perceives in contemplation the principles of the things that are, it will end in God himself, as the cause and beginning and end of the creation and origin and as the everlasting foundation of the compass of the whole universe.”[10] Elsewhere, in exposition of Gregory Nazianzen’s statement that “the sublime Word plays in all kinds of forms,” Maximus speaks of parents taking part in children’s games to attract their attention, and later sending the same children to school and conversing with them in a more mature manner. In the same way God tries to grab our attention and amaze us by leading us through a story, that is through the visible world, in order then to send us to school in aid of a more mature conversation, that is the mystical knowledge of God.[11]

In this stimulating and nurturing of wonder towards our further education, the Church has a central role, imaging the divine activity, drawing diverse people into “the one simple, indivisible, and undivided relationship”—the relationship of one in Christ, one with the true head of the body, Christ. But the Church is also a representation and image of the whole cosmos. The parallels Maximus offers are instructive: just as the interrelationship of the “parts” in the Church’s architecture or liturgy or hierarchical structure are intended as parts of an overall harmony that reveals the Creator, so to are the various “parts” of the cosmos. Moreover, the patterns of relationship and imaging that one may speak of in the Church or in the world are multiple: the Church, for example, images cosmos, human being, and soul.

When he speaks about the Church’s liturgy, Maximus presents the ordered prayers and movements of Christian worship, culminating in the eucharistic liturgy, as calling to mind both the redemptive action of God in Word and Spirit, as well as the movement of human souls into the Church and toward life with God. This symbolic performance both shapes the imagination through a vivid making present in summary and repetition, and draws us towards recognizing not simply the individual deeper meaning of texts and symbolic actions, but the whole sweep of history from creation towards life with God, the whole to which all parts point. Thus complex patterns of language and action are shaped as the framework within which a new world may slowly open in the human imagination.[12]

Maximus draws extensively on the writings that have come down to us under the authorship of Dionysius the Areopagite, and he also deserves brief comment here.[13] Dionysius speaks at length of “hierarchies” in the Church’s structure, in the Church’s liturgical prayer and action, and in the very structure of reality. “Hierarchy” is a term easily misunderstood: it was a term coined by Dionysius to indicate an ordered structure through which the participant may ascend. These symbolic orders are providentially ordained for us, and our ascent towards God is aided by the work of Christ at every level.

Now, while hierarchies move from lower to higher, locating their members, this placing is not an act of restriction (as we might understand the concept in modern Western contexts) but one of arrangement within a complex universe so that ascent is possible.[14] It is the organization of a structure to created speech and existence so that its purpose may be revealed and its vocation realized. And yet, vitally, the one whom he terms the chief hierarch, Christ, is immediately active at every stage and level of the hierarchies he describes.

In the previous paragraph I spoke of “ascent”; the term here signifies the lifting of the heart and intellect toward the divine darkness and light, and (as in Maximus) this is not a one-time process. Rather, such an ascent is that toward which we aim in the constant round of meditation on Scriptural imagery, and participation in the repetitions that constitute the Church’s liturgical life. The new world dawns (in Scheeben’s terms) as we enter the action and language we find ordered for us in Scripture and liturgy. The presence of the divine mystery and the manner in which it lies ever before us in seen particularly clearly, of course, in Dionysius’s famous reflections on the interplay between the cataphatic and the apophatic. We both allow ourselves to speak analogically of the divine life, and yet we know that, because the divine transcends anything we may say, we must also deny the analogy we have offered. This is not to deny the centrality of the propositional, or to deny that Scriptural language is ordered providentially for us; it is to see the completion of that language in our contemplation of the divine transcendence, and it is to allow a new wonder to dawn upon us.

Our life within this symbolic world provides for the Christian imagination a range of images for our desire and our progress—for example, languages of ascent, of journey into the desert, language of imitating and joining in the angelic worship. These languages together enable multiple paths along which the human person may travel. Through them a unitary path is sketched, a unitary vision of the nature and destiny of our cosmos offered, and yet a deeply pluralistic language is offered for reflecting on the subtle colors or shades of light and dark that make up the individual path down which each of us is drawn. And mystery is continuously ingredient both because we are thereby entering a world within which new dimensions continuously open, and because it is the transcendent mystery of God that is being imaged and approached. Describing this movement of the soul through the cosmos both reveals a central topic for Christian meditation, and yet our need to describe it is also a sign of the tragic state in which those of us dwell who have lost the ability to bathe in the imagistic quality of our home.

V.

When we consider the specific nature of theological reflection within this gradual growth into mystery we must speak of the role of precision in thought and argument on the winding path of ascent. Growing attention to the divine mystery that is our context and home is not the antithesis of precise technical language. Rather, attending to theological precision and cultivating attention to mystery should be inseparable.[15] In theological reasoning one of the great tasks is word-care, learning which words the tradition encourages, how it has formed a precise language for speaking of and exploring the divine mysteries, and yet also where it demands of us that we confess mystery.[16] Often this takes the form of identifying precisely what must remains mysterious and why, and usually such precision is an identification of ways in which the nature of God defeats the intellect, or where a feature of the divine economy occurs through the power of God and thus is an act of which we can speak only by weak analogy. In all of this we seek to avoid the danger of saying too much, or claiming too much clarity for our intellects. Doing so would not offer an advance in theology, but a falling away from proper acuity.

The theologian should, I am hardly the first to suggest, nurture in him or herself awareness of the analogy between the liturgical movement of speech and symbolic action, and the patterns of attention necessary for good theological work. Perhaps it is better to say that in the liturgical movement of the mind and body the theologian should find a formation of the attention foundational for intellectual consideration of the Church’s fundamental doctrines. Through careful attention an awareness may grow that the words and terms we use in theology are like the verbal repetitions and icons and movements of the liturgy; even as we struggle for precision and deeper understanding, and as we explore new application of those fundamental themes, by repetition and invocation and repeated veneration we are always also praying for grace, confessing our need of that grace, and waiting upon the Lord.

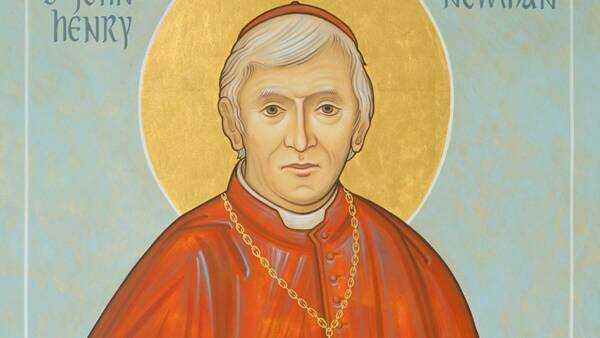

At the beginning of the fifteenth “University Sermon,” a sermon which concerns the task of understanding the development and flowering of Christian doctrine, St. John Henry Newman begins by speaking of the Mother of God as the exemplar of faith. She contemplates, she holds things in her heart, she waits upon understanding. How should the theologian wait? This question is deceptively simple. From one perspective the theologian waits by receiving what has been handed down to us and attempting to grasp it as it is—without rethinking, reinterpreting, translating, or any other such term. From another, the theologian contemplates by trying to grasp how that which was handed on has flowered (the subject of Newman’s sermon). But from another, a theologian waits and contemplates by entering into the Christian universe of signs and learning to think from within this universe. A sudden perception that the movement of leaves in the wind unfurling at the beginning of the summer hints at the interaction of multiple forms, colors, and forces, and that this multiplicity is sustained by the Word to point us to the transcendent power, careful investigation of the development of Christological dogma—both of these are forms of waiting that we must learn to value. The tradition lays out multiple paths that we may follow, paths which enable us to enter more deeply into the mysteries of Christianity and to see those mysteries as a unified whole—and entering into that whole enables us better to swim in the created universe of signs.

VI.

At the end, it is also important to be attentive to the dynamic relationship that obtains between our confession of mystery in this life, and the life of the just with God at the end. The Romanian theologian Dumitru Staniloae offers a short but penetrating account of eternal life (insofar as we can speak of it), which weaves together passages from Maximus the Confessor and Gregory of Nyssa to speak of the character of perfected human freedom. In short compass the picture that emerges offers a particularly clear version of the tradition which sees the eternal life and the beatific vision as an eternal progress. Quoting Gregory, Staniloae writes, “because the supreme good is infinite by its nature, communion with it must necessarily be infinite, that is to say capable of eternally expanding.” For Staniloae, human nature may now experience the constant tension between our own finitude and the infinite that is a truly free human being’s desire. In the life of eternity, this tension is not simply overcome through a fusion with the infinite, but through a participation in the divine plenitude, a taste of the infinite (a taste which contains the whole) which draws us on:

This does not mean an advancement in an endless linear time, for it happens at the end of time, but into an infinity that is continually tasted but that never satiates. If the life to come is movement, as St. Maximus the Confessor says, but a static movement or a mobile stability, a movement that eternally maintains beings in him who is, strengthening them and making them grow at the same time.[17]

Similarly, our mode of knowing is no longer the discursive movement from lack to fullness with which we are familiar in this life. The mystery of the divine existence is thus not somehow dissolved because it is now understood, rather its status as mystery is now transformed into the ever-unfolding life into which our existence may ever travel.

Further Reading

Jean Corbon, The Wellspring of Worship, tr. Matthew J. O’Connell (San Francisco CA: Ignatius Press, 2005), chps. 1-4.

St. John Henry Newman, “Mysteries in Religion,” Plain and Parochial Sermons, vol 2, no. 18 (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1908), 206-15.

Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, tr. Cyril Vollert SJ (St Louis MO: Herder, 1947).

Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of The Eastern Church (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1957), Chp. 2.

[1] 1 Cor 2:7. I dedicate this piece to the memory of Richard Bondi, one of the very gentlest of souls. I would like to thank Stephen Holmes, Fr Andrew Summerson, and Medi Ann Volpe for comments on an earlier draft.

[2] Here I summarize some features of Louis Bouyer, “Mysterion,” Mystery and Mysticism. A Symposium (London: Blackfriars Publications, 1956), 18-32.

[3] See, from a Thomist perspective, Fritz Bauerschmidt’s wonderful essay “The Body of Christ Is Made from Bread: Transubstantiation and the Grammar of Creation.”

[4] To some it will be notable that I have turned to Scheeben, and stepped over Rahner’s 1959 series of lectures translated as “The Concept of Mystery in Catholic Theology,” Theological Investigations IV (Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1966), 36-73. I have done so because while his attempt to argue that all the theological “mysteries” are only aspects of the mystery of God is helpful, his anthropocentric approach renders him uninterested in the role of creation (and liturgy) in educating us in wonder, and he is unable to recognize the value in speaking about a plurality of mysteries—it does not seem to occur to him that there is not only a venerable tradition of speaking about theological mysteries in the plural, but also many Patristic discussions of God’s economies in the plural. The plural reflects an insistence that the human mind needs to reflect on a range of real events and actions, and propositional statements enabled for us in the created order. Rahner’s criticisms of his Scholastic peers are not entirely wide of the mark with reference to his charge that they often see mystery as primarily an attribute of statements, but their accounts also offer a rich tradition of reflection on the spirituality of knowing that he ignores. See, e.g., Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P., The Sense of Mystery: Clarity and Obscurity in the Intellectual Life (Steubenville OH: Emmaus Academic, 2017), 289ff & 94ff on mystery in Thomas.

[5] Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, tr. Cyril Vollert SJ (St Louis, MO: Herder, 1947), 7ff.

[6] Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, 762ff.

[7] Gabriel Marcel, The Mystery of Being. Vol. I: Reflection and Mystery, trans. G. S. Fraser (South Bend, IN: St Augustine’s Press, 1950), 204ff.

[8] Olivier Clément, “Mémorial Vladimir Lossky 1903-1958,” Messager de l’Exarchat du Patriarche russe en Europe occidentale 30-31 (1959): 137-206. The quotation here is to be found in translation in Nicholas Lossky’s introduction to Vladimir Lossky, Seven Days on the Roads of France, tr. Michael Donley (Yonkers NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2012), 17.

[9] Thomist theologians, emphasizing the fulfilment of the intellect in the beatific vision, will always feel somewhat unhappy about the manner in which a figure such as Lossky presents the primacy of the apophatic. But there is no simple opposition here (we are all caught between John 1:18 or Ex 33:20 and 1 John 3:2), and questions may be asked of both sides in order to indicate points at which there should be a common conversation. How might Lossky have described the intellectual content of a dogma, and its relationship? Given that the fulfilment of the intellect involves a union of knower and known beyond what we may now experience, and is inseparable also from the fulfilment of love, how far may we also understand the beatific vision as both intellectual in this unique sense and yet also involving an endless progress into the mystery of God? There is a good introduction to Thomas’s own discussion in Reinhard Hütter, Bound for Beatitude. A Thomistic Study in Eschatology and Ethics (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2019), 389-409. It is also fairly intrinsic to modern Orthodox accounts of mystery to cast a distinction between the Greek and Latin fathers that, I would argue, is often far too simplistic.

[10] Saint Maximus the Confessor, On the Ecclesiastical Mystagogy, tr. Jonathan J. Armstrong (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2019), here p. 53. One of the most helpful of recent discussions showing the links between liturgy and the mystery of God is Jean Corbon’s justly famous The Wellspring of Worship, tr. Matthew J. O’Connell (San Francisco CA: Ignatius Press, 2005).

[11] Maximus, Ambiguum 71.7. Translated in Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers. The Ambigua. Vol 1, ed. & trans Nicholas Constas (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 323-5.

[12] And here is where iconoclasm is so great a danger by taking from us the resources given us by tradition for ordering the movement of our imaginations towards the divine.

[13] Dionysius’s corpus may be found translated in Pseudo Dionysius. The Complete Works, tr. Colm Lubheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987). For an introduction to Dionysius see Andrew Louth, Denys the Areopagite (London: Continuum, 2002).

[14] And again, lest this be misunderstood: Dionysius is not speaking about ascent through the earthly hierarchy itself. Rather, the complex structure of the hierarchy allows each member to ascend spiritually towards God.

[15] When we consider apologetics, there are some who find the prioritizing of techniques from analytical philosophy to be an apt tool in part because those tools supposedly render clarity and are appreciable to others within the academy. Au contraire, I would suggest that the object at which we aim, God, demands of us that we be clear what clarity may and may not be achieved, and that an essential part of providing an apologetic for theological reasoning is to show the necessity of reasoning in the light of mystery if the world or its Creator is to be approached. Similarly, an overly strong focus on the style of argument taught by such analytical traditions may divert attention from the true nature of theology’s object: see e.g. Simon Oliver’s review article, “Analytic Theology,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 12 (2010): 464-475.

[16] And here we really do see one of the strengths of the long scholastic tradition, understood as something which begins in the early Trinitarian and Christological disputes, continues into medieval scholasticism, and finds many echoes in later “manualist” traditions.

[17] Dumitru Staniloae, The Experience of God. Vol 6. The Fulfilment of Creation, tr. & ed. Ioan Ionita (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2013), 200.