in memoriam Fr David Burrell (1933-2023)

I.

The notion of communion is one that has been highly significant for Catholic theologians in the past couple of centuries. Christians are, in Christ and in the Spirit, one—even as this reality is hidden by our sinfulness and failures of communion.[1] How, then, may this reality be made visible in our lives, and how may the ordering of the Church best reveal the unity at its heart? But because the communion that Christians seek is one rooted in the Spirit animating Christ’s body, it is a unity that mirrors the divine communion; Christ himself prays “that they may be one, even as we are one” (John 17:22). Thus, it is vital to ask how we may envisage Father, Son, and Spirit as a communion if we are to speak appropriately of the divine and of the human.

Lumen Gentium makes use of the term communion at key points. The Spirit “unifies the Church in communion and ministry (in communione et ministratione unificat)” (4), the Church is established by Christ as “a communion of life, truth and love (in communione vitae caritatis et veritatis constitutus)” (9). In the new Catechism, “the Christian family is a communion of persons, a sign and image of the communion of the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit.” (§2205). If Christian thinking always takes its cue from meditation on the nature of God and God’s actions, then asking whether the Trinity is a communion is a vital task for the theologian.

II.

The best point of departure for considering what it means to think of the Trinity as a communion is to focus on the patterns of biblical language. One of the most fundamental reasons that one might want to think of Father, Son, and Spirit as a communion is because the Scriptures constantly speak of the three as distinct agents. Thus, for example, Romans 8 speaks of God “sending his own Son,” of the Spirit as helping us in our weakness and as interceding for the saints, and Romans 6 speaks very clearly of Christ as dying, rising, and living with God. The very beginning of Hebrews, while emphasizing that the Son is above the angels, does so by using the language of one agent addressing another: “To which of the angels did God ever say, ‘You are my Son’” (Heb 1:5). And, in later centuries, confessions of faith, copying as they do much biblical language, often have a story like structure, attributing actions to each of Father, Son, and Spirit.

But even here we must attend carefully. Scriptural patterns of language constantly challenge our imaginations not only to think of Father, Son, and Spirit as distinct individuals. Look, for example at the language of John 17:20–23:

I [pray that] those who believe in me . . . may all be one; even as you, Father, are in me, and I in you . . . . The glory which you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one.

Here, strangeness marks this language of agency. Father and Son are two who are “in” each other; we must recognize the two as two by the very grammar of the sentence—Father and Son—and yet we are also pulled up short when the strangeness of one character being “in” the other defeats our imagination. In the same way, the prologue to John’s gospel speaks of the Word being “with God” and “was God.” The Word is there with God, leading us to think of God and Word as two . . . and yet the Word also is God; there is no gloss or explanation, we are left to ponder a variety of interpretive paths forward. And thus, even the language that Scripture uses that most makes us think about Father, Son, and Spirit as distinct individuals often carries with it a questioning of any simple reading, forcing us to ponder.

III.

It is, however, not enough to note the strong presence of agential language to describe Father, Son, and Spirit, and then note the ways that Scripture forces us to question how we interpret such language. We must also attend to another set of ways in which the Scriptures speak of the Son in the context of Jewish and Christian belief in the uniqueness and unity of God. At Hebrews 1:3—just before we come to the agential language of Hebrews 1 that I mentioned above—we find the Son described as the “out-shining (apaugasma) of the glory of God” and as the one who “bears the very stamp of his nature.” In the first place, such texts are using language intending to do far more than identify the Son as a distinct individual; this language not only begs metaphysical questions about what it means for one to be the out-shining of another, but they also emphasize that the Father is the one from whom the reality of the Son comes, and the one who has ordered the Son’s existence and mission. The Son’s exalted status is clear, but it is a status that does nothing to compromise the Father’s place as the one who is throughout the epistle simply termed “God.” Exactly the same things might be said of that which we hear in Colossians 1:

He is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created . . . . He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

See again an order that does not compromise the existence of the One God. But also note that Christ is the “image of the invisible God,” the one “in” whom “all things were created.” The sketching of these complex relationships requires us to reimagine our assumptions about what it means to speak of discrete individuals.

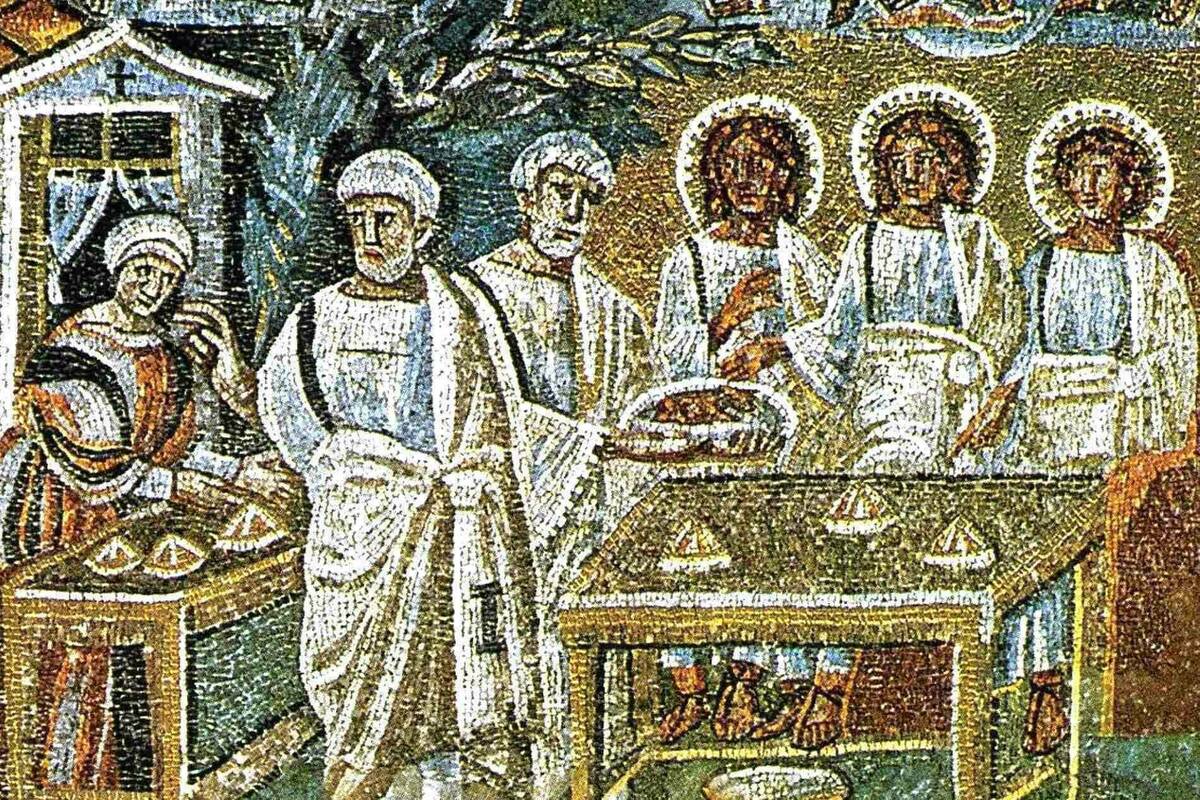

When we see such passages we should remember that the earliest Christians drew on traditions that flourished in the world of post-exilic Judaism, where a variety of terminologies are used to speak of one who is with the Father and yet always dependent on him. In the vision of Daniel 7, we have this in very anthropomorphic terms—“there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and kingdom” (Dan 7:13–14). In the book of Wisdom, the eponymous character, “the fashioner of all things” and “an associate in [God’s] works,” is hymned in terms beyond the simply agential: “she is a breath of the power of God, and a pure emanation of the glory of the almighty” (Wis 7:25). This language is itself a complex meditation on the earlier Wisdom texts of the Hebrew Bible, and on all these texts early Christians drew when they sought to speak of what was in Christ. In all of them, the fundamental monotheism of the Judaeo-Christian tradition is maintained, but maintained by giving the Wisdom of God a unique status of closeness to and from God.

As Christians confessed Jesus Christ as the fleshy presence of this Glory or Wisdom or Son, it is no surprise that a wide variety of different traditions of reflection grew up under this broad umbrella, until the Spirit led the Church to summarize some of its most fundamental beliefs in the principles that the Son was God eternally generated from God, light from light. Such statements, as we find them in the Creed of Nicaea maintain the principle that the Father is the source of all, and constantly drive forward and yet trouble our human imaginations as we try to grasp what it means when we speak of the eternal generation of one divine light from another, such that there are two and yet two united in one Godhead.

IV.

“Spirit” is a deeply complex term. John 4:24 tells us simply that “God is Spirit,” and thus we are easily led to wonder if uses of the term names only divinity rather than a distinct actor in the divine drama. In the Letter to the Romans we read, “But you are not in the flesh, you are in the Spirit, if the Spirit of God really dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him.” It is easy for the modern reader to assume that “spirit” here should not have a capital letter, and that it is “merely metaphorical,” just as we now speak of someone’s “spirit” and do not designate a distinct reality. But such a reading is too easy, and misses the manner in which the very same letter speaks also of the Spirit as an individual actor in the divine-human drama: “The Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we know not how to pray as we ought, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words” (Rom 8:26). Once again there is a complex background here.

There is a line of reflection on the nature of creation that runs through the Hebrew Bible, and on which the early Christians reflected deeply. In Genesis God creates (in the singular and in the plural), in Psalm 32:6 and in Judith 16 God creates through Word and Spirit, and these texts draw on complex Jewish traditions which accord both Word and Spirit quasi-independent status as realities acting on God’s behalf. These two realities are rarely distinguished clearly, but that does not mean that the Spirit is not often treated as a distinct agent sent by God and working toward divine ends. Of particular importance is the representation of the Spirit as angelic, sometimes as “the angel of the Lord.” As an example of the intermingling of traditions, one might glance at the strange text called The Ascension of Isaiah, a text that comes to us from a Jewish origin but through the hand of a Christian final editor working sometime in the 200s of the Christian era. Isaiah speaks in the Spirit, as the Spirit has inspired the prophets, and it is the “angel of the Holy Spirit” who makes it possible for the prophet and those who follow him to ascend to God. But, throughout these texts—those of the Hebrew Bible, our New Testament and beyond—the divine monarchy is preserved: as the Spirit of God and of Christ the Spirit works from and toward the one Lord.

Christians will eventually give a clearer form to the distinction between Word and Spirit preserving both the agential language and the complex ways in which both come from and depend on the Father. It is fascinating that in the late fourth century and early fifth century, when the status of the Spirit as one of the co-equal divine three is first expressed in simple Trinitarian formulae, a number of theologians argue that this is a truth that has taken time to be recognized, one held over until the co-equality of Father and Son was confessed clearly. Augustine of Hippo gives one of the most interesting riffs on this idea, suggesting that the Spirit, as person, is the love who comes forth from Father and Son, from eternity that which joins Father and Son, and that only after the deep meditation of generations of Christians on the Scriptures (and on God’s life among them) was it appropriate that this truth be stated for our belief.

Given the agential language of Scripture, then, it is natural that we speak of Father, Son, and Spirit as distinct persons—and quite likely that, in a culture that so prizes the individual as ours—that we go on to imagine their communion as if we were considering human persons. But such a project always comes up against the complexities of how Scripture speaks of the three. The final formed teaching of the Church that the three are irreducibly distinct, and yet together one God, does not so much remove earlier ambiguity as it defines for us the mystery of the divine life insofar as we are able to speak of it. And here, mystery should not be understood primarily as an unfortunate consequence of human incapacity (although it is in part that), but as a gift of knowledge, a gift that calls us constantly back to the difference between human and divine life.

V.

My next step is to reflect further on the importance of the Trinitarian order. The Father is the one from whom the Son and Spirit appear. The Father, using terms that eventually became traditional, is the one who eternally generates the Son and spirates the Spirit. These terms are used of unique relationships and thus are not finally comprehensible to us, even though they do have clear content. Thus, to say that the Son is generated is to say that the Son is not created like all else; it is to say that just as human parents generate children who share their nature, so the Father “generates” a Son who shares all that he is; to say that the Father eternally generates is to say that divine generation is not an act that happens and then is over, rather it is intrinsic to the Father’s being that the Son is eternally generated into existence. The Father is one who from eternity gives completely of himself to give the Son reality as the fullness of the divine life. Human fathers may only be called by that title when they have children; God is Father from and in eternity. Similarly, to say that the Spirit is breathed—spirated—is to mark the distinction between Son and Spirit (the Spirit is not a second Son), and it begins to point toward what is distinctive about the Spirit, as the one who is breathed on the disciples drawing them into unity; but how the Spirit might be understood as the love that, in some sense, draws together the Father and Son who from eternity possess the fullness of love transcends our grasp.

But, while these terms emphasize the role of the Father as source, they should also be understood as telling us much more about the Father. The Father is one who is the source from eternity of a communion. It is intrinsic to what the Father is that he generates (as we have just seen) one who returns the love that brings him eternally into existence; it is intrinsic to the Father that he breathes the Spirit on the Son in his generation of the Son, and in doing so gives it to the Son that the Son will also breathe the Spirit. There is no sequence of relationships here, but an eternal willed bringing forth of communion as the expression of what is to be divine.

Sometimes the statement, derived from Latin theologies of the early and medieval periods, that the Spirit proceeds “from the Father and the Son” is taken to undermine the Father’s role in the Trinity. This is, I suggest, a mistake. In the first place, these theologies have always insisted that the Father gives it to the Son that the Spirit proceed from him. The Son is not undertaking a secondary and subsequent operation after the Father has acted, but is from eternity constituted as one who breathes out the Father’s Spirit as his own. And thus, in second place, we may see this theological vision as another way of securing the Father’s role as the source of Son and Spirit, but as the one who orders a communion in which it is given to the Son to give rise to the Spirit of that communion. The Father gives the life that he is (John 5:26) to the Son, including the breathing forth of the Spirit who is the love between Father and Son (though, of course, there is no temporal succession here). This vision is not opposed to one that emphasizes the Father’s role as the sole generator of Son and Spirit (these visions may mutually complement); rather, it is one that finds new ways of emphasizing the Father as the source of true communion.

VI.

Before reaching a conclusion, we need to take another step back and think about how we best consider the questions we have discussed, drawing out some things that I have been hinting at in many of the preceding paragraphs. The first thing to say is that the emergence of Trinitarian theology was interwoven with a particular sense of how to read Scripture. Scripture, for those thinkers who best articulated the classical doctrine of the Trinity (thinkers of the early and medieval Christian periods), is providentially gifted and always a trustworthy source for thought. At one level, Scripture speaks directly and clearly; at another, it uses allusive similes, metaphors, and terminologies the hidden depths of which we are called upon to plumb with care. The very form of Scripture’s language begs complex metaphysical questions; for example, when the Word is said to be “in” the Father at “the beginning,” or the divine Wisdom is said to be a breath of the power of the almighty, we are invited to use the resources at our command to interpret the text. The human intellect needs to be reformed, it needs to learn again to envision the created order and the creator in whom it rests, and a key part of that reformation is the overcoming of our tendency to reach too far and fail by accommodating all to our material and temporal perspectives. In enabling us to talk truthfully about reality, Scripture and the doctrinal matrix that we have been led to draw from it have enabled us to grasp better both our limits and the transcendence of the life in which we are enfolded. And so, our thinking about the Trinity is a plumbing of Scripture’s depths by means of the doctrinal matrix to which the Spirit has led us, it is always an entering of mystery, both to make clear what may be made clear and to recognize where mystery attends as a gift towards our reformation.

While we are considering how to think about the Trinity as communion, it is also important that we are wary of talking about “models” of Trinitarian theology. Many narratives of pre-modern (and modern) Trinitarian theology tell us that some theologians focus on “social” models, likening Father, Son, and Spirit to three people, while others focus on “psychological” models, likening Father, Son, and Spirit to three faculties of the mind. This way of differentiating traditions does not reflect what the evidence shows us, and is deeply unhelpful for the theological enterprise. While a few writers do make extensive use of one particular Trinitarian likeness or analogy, most combine different images and terminologies, and our task as readers is to see how these resources are used in the ebb and flow of a text, not to try and pigeon-hole authors into artificial categories. It is vital that we see how far such resources are understood as pointing us toward that which lies beyond us, how far they are seen as mutually informative, and how far their use is ultimately to be transcended (or not). It is these questions that should preoccupy us. It is certainly, for example, that aspects of mental language are used by different authors in a variety of ways throughout the tradition (and are perhaps simply inherent in the use of the term “Word”!), although these very same authors may also use quite other analogical images and terminologies. Even when a particular set of mental relationships takes center stage (as for example in St. Thomas), how they are used to lead us toward the recognition of the divine mystery is central. Thus, different resources are used not so much simply to build up a picture of the Trinitarian relationships in the mind (although, of course, they are also this), as they are way stations helping an author describe the mind’s struggle to understand and speak of that which lies beyond us.

Following in the same vein, we must be very careful about how we make use of abstract philosophical models of unity and diversity in the Trinity. Since the latter decades of the fourth century, theologians have made some use of such models as part of their attempts to show the rationality of Trinitarian teaching, even as they have also proceeded to emphasize that the reality of the divine life transcends our grasp. In recent decades especially, scholars with strong philosophical interests have spilled a lot of ink exploring these philosophical models in abstraction; treating them as if they were the totality of a given theologian’s vision of the Trinitarian life. There is, of course, nothing wrong with considering the coherence of that which a theologian offers, and yet such investigations are of little theological use if they do not also attend carefully to the context of those discussions and to the ways in which they are used, to the ways in which they are part of a discourse aimed at directing the heart and intellect toward the divine mystery.

VII.

The Trinity, then, should be thought of as a communion, but we must remember that we speak always analogically. There is a relationship between the notion of communion as we experience it—or seek to experience it—and the communion that God is, but our minds are always reaching toward the communion that God is. It is helpful to think about the sort of analogical relationship involved here as one in which the triune life is true communion, and all communion in this world is only an imitation of that divine communion. God has constituted creatures as loving and desiring creatures, as creatures who seek communion with God and with each other. The communion that we desire is both to be found in God, and the model for that communion is the divine life.

One further principle of classical Trinitarian theology that offers yet another window to the divine communion is that each of the three persons is the fullness of what it is to be God, and the three together are the one God. The Spirit, for example, is not fully God only when considered with Father and Son, but is fully God and yet also fully God with Father and Son. This is perhaps the mystery of divine unity and communion and it is hardest to grasp. As we realize that the only true communion is that of the divine life and that this communion does not contravene the unity of God but in some sense expresses the reality of that unity, we can begin to realize that while we speak of unity and distinction in God, we are not simply speaking of a paradoxical opposition, but of a mystery in which true unity is the triune life of God. What we experience in this world is a sign that points away from our failures in communion and towards true unity and distinction as the life in which we are enfolded.

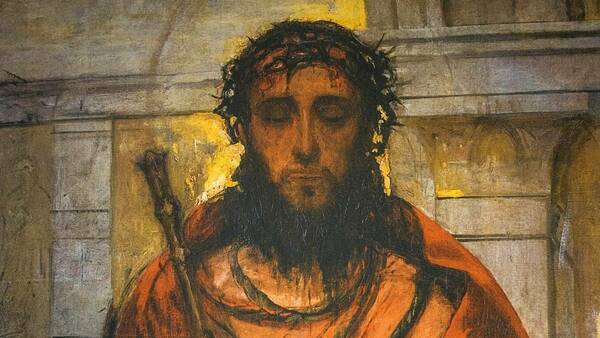

As I have already hinted, understanding the Trinity as communion provides the foundation on which we may grow in knowledge of creation and redemption, and particularly of humanity’s true ends. All things are created in the Word and, as such, they are in God. All things are redeemed by being united to Christ through the work of the Spirit, and this is to be enfolded in the life of God. When we speak of God sending the Son to die for us, we speak of a mystery between two who eternally work together—as I explored in my discussion of Christ’s sacrifice. Such a Trinitarian perspective forces us to work hard to avoid excessive anthropomorphism, and as we learn to do so we are drawn more deeply into the love from which and within which God saves. In hard thinking, in trust, in prayer, and in contrition we are called to ascend—indeed, we are drawn into ascent—toward vision of this, the one true communion:

O Most Holy Trinity, have mercy on us; O Lord, cleanse us of our sins;

O Master, forgive our transgressions; O Holy One, come to us and heal our infirmities for the sake of your name.

Further Reading

Boris Bobrinskoy, The Mystery of the Trinity (Crestwood NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1999).

Gilles Emery, The Trinity: An Introduction to the Catholic Doctrine on the Triune God (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2011).

Gilles Emery & Matthew Levering, The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

John Damascene, On the Orthodox Faith, trans. Norman Russell (Yonkers NY: St Vladimir's University Press, 2022), §8–14, pp. 70–96.

[1]. With many thanks to Medi Ann Volpe and Fr. Andrew Summerson for their comments on an earlier version.