The fourth century was a time of great upheaval and controversy for Christianity. Early in the century Constantine fought bitter battles around the Mediterranean to “reunite” the Roman Empire under his solitary command. Just as Imperial policy began to formally tolerate Christianity, a significant dispute arose between the Patriarchal Archbishop St. Alexander and a clergyman in Alexandria named Arius. Numerous synods met in an attempt to resolve their dispute.

The Council which met in Nicaea in the year 325 condemned Arius’s doctrines. Arius had taught that the Son was somehow less than the Father. This was his way of making sense of the Incarnation and the Son’s role as mediator. The Catholics at Nicaea professed belief in the Trinity of coequal Father, Son, and Spirit, focusing especially on the equality between Father and Son. They used a controversial term, homoousion in Greek, which could not be found in Sacred Scripture. But the issue did not remain simply a theoretical difference.

The Arians formed a “church” with complete alternative jurisdiction, hierarchy, property, and missionaries. They claimed to be the Christian Church to the exclusion of the Church which recognized the Creed of Nicaea from 325. The feeling was more or less mutual. When St. Alexander died, his star deacon Athanasius succeeded him as Patriarchal Archbishop. But St. Athanasius was exiled from his see in Alexandria multiple times for his Pro-Nicene Catholic Trinitarianism. The five and a half decades between 325 (Council of Nicaea I) and 381 (Council of Constantinople I) saw dozens of synods with various factions waxing and waning in power.

Roman Imperial authority sometimes supported Catholicism, sometimes Arianism, and sometimes attempted compromise. Those years also saw the Arian “church” grow in stature. When the bishops met in 381 in what was effectively the Imperial capitol of Constantinople, they upheld the Trinitarian faith of Nicaea and opposed the Arians in a new way. The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed they adopted in 381 is the one most Christians profess today (with the noted exception of the later filioque concerning the Holy Spirit’s procession from the Father and the Son). The bishops argued that the creed of the 380s was an articulation of the same Faith that had been expressed in 325.

Nevertheless, they changed the explicit grammar of the profession of faith. Where there had been three prepositional phrases beginning with “in” to explain the faith, they added a fourth. In adding a fourth “in” to the “We believe,” the ancient Church made a profound statement about the connection between the Trinity, the Church, and Faith. One cannot separate belief in the Trinity from belief in the Church, nor can one relegate belief in the Church to some subordinate category of doctrine. This point is as relevant today as it was then.

The version of the Creed adopted in 325 is essentially a single sentence with the main subject and verb “We believe,” that includes three prepositional phrases: “. . . in One God the Father . . .,” “. . . in One Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God . . .,” and “. . . in the Holy Spirit.” Readers of the history of Christianity are sometimes shocked to see the abrupt ending of the Creed from 325 followed by the anathema of Arian sentiments. There are no further words explaining the Holy Spirit in the Creed from 325; the simple faith “in the Holy Spirit” concludes the sentence. The grammar of the Creed was a simple subject with a single verb explained by three prepositional phrases that announce the persons of the Trinity. After the Council in 381, the grammar of the faith includes a fourth prepositional phrase: “…in One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.”

It is true that the historical witnesses from 381 are more difficult to assess than my simple narrative here can explain. In some cases, we must rely more on later memories than on stenographer’s notes from the events of 381, but this is often the case with ancient history. Manuscripts for the Creed also vary on the “four marks” of the Church, sometimes listing them as three (One/Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic), but it is clear that the Creed fully intends to add belief in the Catholic and Apostolic Church, which is singular (one) and set apart (holy).

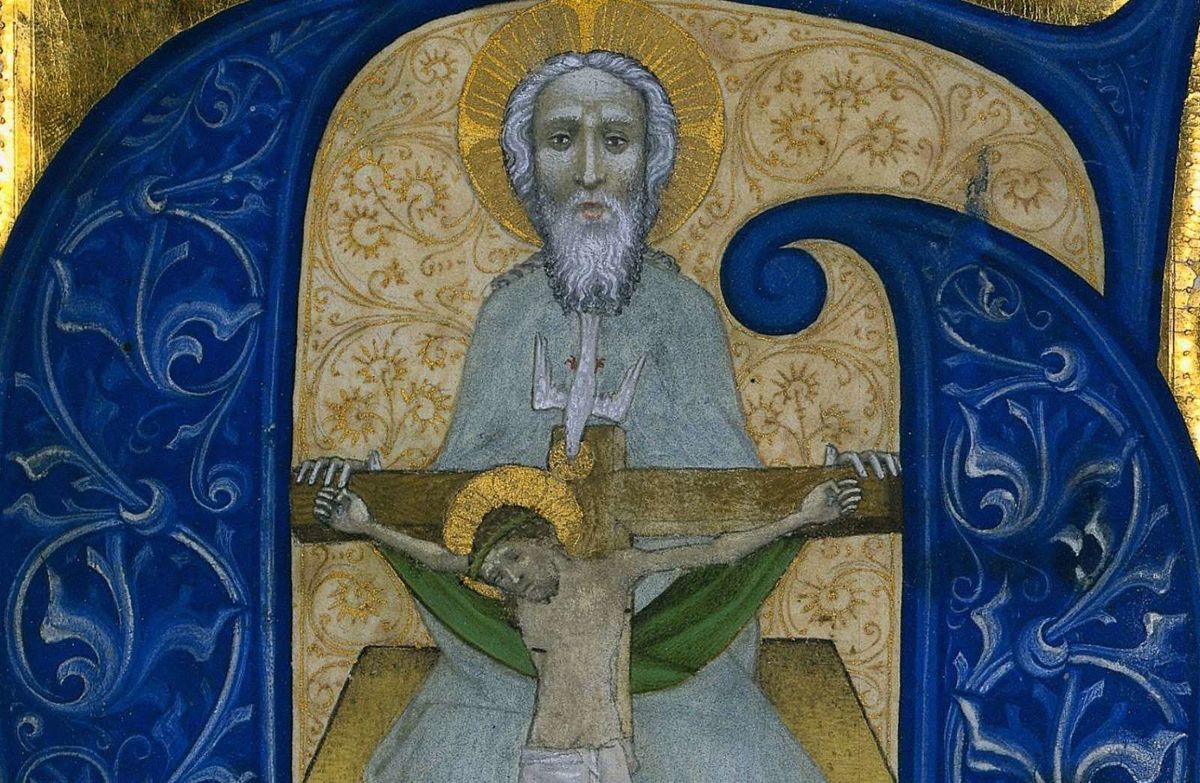

Furthermore, the fathers of Constantinople suggest that this is to be held at the same level of “belief in” as belief in the Father, Son, and Spirit. This is profound and deserves continued meditation. In a period of dramatic and even violent rivalry between two claimants to be the Church which offers salvation, our Church understood itself to be tied uniquely to the most profound mystery of existence, truth, and love, namely, the God who is Trinity. Our Church belongs to the Triune God.

Other Creeds used in the liturgy, such as the Apostle’s Creed, have a similar, but distinct grammar. The Church is placed with the Holy Spirit in the same grammatical construction, and this deserves separate meditation in other contexts. The Nicene Creed as expounded in Constantinople and professed even today has a distinct grammar. The order of the four objects of belief suggests a few prominent paths for meditating on our Catholic Faith.

First, belief in the Church is as important as belief in the Father, Son, and Spirit. As articulated in the Creed, this includes the most fundamental mystery of the Trinity and the second most fundamental mystery of the Incarnation. (CCC §234 & §463) We should speak of the mystery of the Church with the same awe, wonder, and theological tools we use to speak of the mystery of the Trinity and the mystery of the Incarnation. Father, Son, Spirit, and Church are equally objects of belief, even though the Church is not one of the Trinity. (CCC §750)

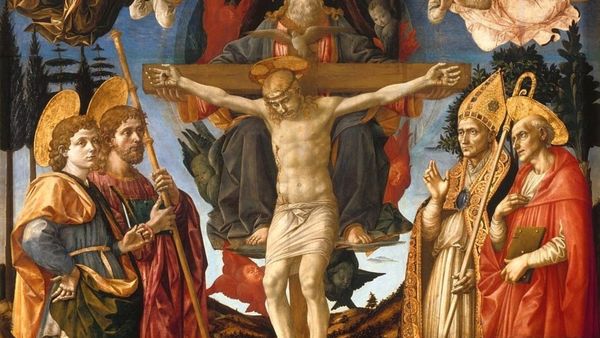

Second, following the initial order of the four beliefs, we see that only in professing the Trinity can we come to understand the importance of the Church. An ecclesiology articulated prior to belief in the Trinity will fail. This is precisely what the Arians had done. They had attempted a Church while denying the Trinity and the full mystery of the Incarnation of the Son. Their project met with the initial success that often accompanies human endeavors which have only the pretense of theological virtues, but it eventually failed. The Arian “church” has long since faded away.

One could say the same about an ecclesiology attempted without the light of the Incarnation (or pneumatology, though the Holy Spirit deserves careful consideration in a distinct context, given the controversy over the filioque and the Apostle’s Creed). An ecclesiology which is not rooted in genuine Christology or which is absent a vital pneumatology will fail, according to the articulation of the faith from the First Council of Constantinople. Given that the Arians were rooted neither in a genuine Christology nor a life-giving pneumatology, their attempt at Church was bound to fail. They had neither body nor soul. They wanted to found a Church without the Trinity.

Third, one cannot profess the mysteries of the Trinity and Incarnation without belonging to the Church which is One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic. We should say the same about the Spirit, though again due consideration must be given to the intricacies of the Creed and the Spirit with later controversies and developments. The Creed is, after all, a liturgical statement made from one who is a member of the Body of Christ and is usually made within the walls of a Church. Pope Benedict’s meditation on the “Ecclesiastical form of faith” in his Introduction to Christianity guides our reflections here.

The Creed is first professed at baptism and is continually repeated in the Communion of the Church. In no sense does one profess the Trinity alone; neither as a solitary human as if my faith were not also our faith, nor as if one could profess the Trinity independently of the Church. Given that the Arians refused to belong to that Church, it is no wonder that they could never find meaning in the profession of the Trinity, true Christology, or genuine pneumatology. One could make a similar claim about modern “spirituality” attempted outside the Church and without reference to the Trinity; it, too, will fail because it will not be connected to the Spirit, who is One of the Trinity and is “of the Father” and “of the Son.” Worse yet, it may attempt a spirituality rooted in some other spirit who somehow exists apart from the Father and Son.

Application of the lessons from the fourth century to the twenty-first century should be obvious, even if difficult. The Second Vatican Council reflected on the Church and the Trinity in the opening of several documents aimed at the Church (e.g. Lumen Gentium §1-4, Christus Dominus §1-2, & Gaudium et Spes §1). It should come as no surprise when one outside the Church struggles to find meaning in the Trinity. We who are evangelists know this intimately. We attempt to give reason for our hope and our faith to those who do not yet have the faith by which we gain a glimpse of the God who is Triune Love. We realize we cannot express faith in the Trinity without also explaining our faith and belonging to the Church. We fail when we attempt to evangelize as though we could do this on our own, either separate from the Church or separate from God. We who are catechists know this intimately.

Those who live a life animated by the Trinity, who is self-giving love, are the same who understand and love the Church, who is the means of salvation and entry into the life of the Trinity. We find it easy to hand on the details of the faith to those who live the life of faith in the Father, Son, Spirit, and Church. We find it difficult to speak of the mysteries to those who separate the Trinity and the Church. Such a disconnect is not a minor theoretical detail which is otherwise reserved for theological specialists.

Theory and practice are united by life in the Father, in the Son, in the Spirit, and in the Church. For those who lead the Church, when the average parishioner struggles to connect in any meaningful sense to the doctrines of the Father, Son, and Spirit, we should understand this as a critique of our way of being and leading the Church. Primacy within the Church must be parallel to the monarchy of the Father, which is expressed as order without subordination. More precisely personal, it should make us wonder to what extent we have immersed ourselves in the true Church if we find no meaning in the Trinity.

If we cannot find in our own understanding of the Church an Icon of the Trinity (see: Archbishop Bruno Forte’s work by that title), we may stand more with the fourth century Arians than with the fourth century Catholics. When we attempt to articulate the mystery of the Church and find no need to first meditate on the mystery of God, we should recognize the danger that we are simply reflecting in our own mirror and attempting to discuss a “church” in our own image, and not the Church who is rooted in the Trinity.

This is the Creed we continue to profess at Eucharist after Eucharist, joining our voices to those of the past millennium and a half. Let us continue to meditate upon and to be the Church which springs forth from the Most Holy Trinity.