When reality is recognized as event, as originating in the Mystery, this produces an incomparable intensity in your own life.

—Julián Carrón, The Radiance in Your Eyes

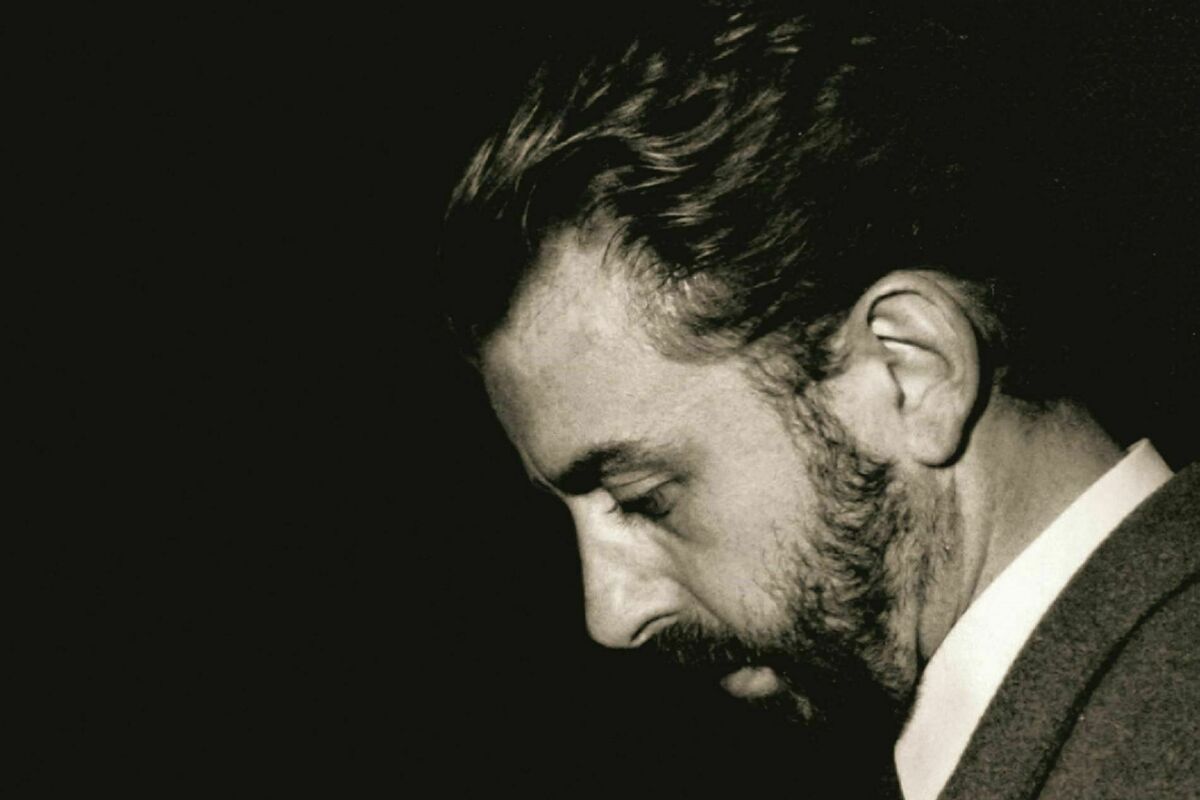

His right hand came off the table, slowly rising. The thumb out, the palm turned up—the gesture of an orchestra conductor. The other hand remained still, close to the microphone, the glass, the bottle of water. It was poised to unite itself to the ascending movement, to underline the fundamental, decisive, indispensable point.

The voice went up along with the hand. He had been speaking for a half hour, and there was no more trace of the tiredness with which he started. In the seats, not a murmur, not a movement among the 150 doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals who filled the conference room at the Cesena Savings Bank. Gone as well was the irritation at the long delay to begin the conference. Many already knew him, others were hearing him for the first time, but everyone understood after five minutes that this was not the usual speech from a representative of the healthcare world. They had been attracted by the title of the meeting: “The Patient. A Person before a Sickness.” Many of them, above all those who had not met him, imagined that they would be listening to a technical analysis followed by some ethical considerations.

If anything, they thought that the speaker might take up and develop the concept that Enzo Biagi had written about that morning on the front page of Corriere della Sera, dedicated to the “absurd struggle between lawyers and doctors,” an editorial titled: “And the Patient Remains in the Middle.” That Friday, March 12, 1999, just like every day in Italy for the last few years, everything was reduced to legal battles and ethical considerations. This time the doctors were caught up in it through one of the many investigations of that period. “I do not think that medicine, and journalism, are ‘missions,’” wrote Biagi, “but surely they are careers that are founded on an ethic. Not to lie, to respect facts, and to remember the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ which teaches: to observe the body, to explain the diagnosis, to determine a treatment. And, I add, taking a liberty, to release tax returns.”

Words that incarnated the spirit of the times: Hippocrates and receipts. Just reflections, correct reflections. But for the speaker that evening, there on the stage, these reflections were not enough to understand his work and his life. The right hand had now come up to his eyes, as if he wanted to hold in the air the weight of what he was saying. The left hand was preparing to reinforce the right, bringing the hands together, resembling a gesture of offering. In the course of the day, before arriving at the conference hall, those hands had entered three human bodies. They had worked with the scalpel and the tools of the trade to search the nooks of the digestive system, to inspect, explore, repair. Those hands were guided by almost thirty years of study and experience, by masters from whom he had learned, by travels overseas for training, by techniques developed with colleagues.

That morning, he had operated in his ward at Sant’Orsola Hospital in Bologna, and in the early afternoon, he had performed a second surgery, nothing particularly complex. “Soon after he did a third surgery, a patient that I had directed to him with a cystic lesion on the left lobe of the liver,” recalls his friend Raffaele Bisulli, director at San Lorenzino Clinic in Cesena, remembering that Friday more than twenty years ago. The operation had been prolonged because of the decision to do a surgery that was more radical than they had foreseen. “The surgery went perfectly, three and a half hours of work. In the meantime, it was getting late for the meeting that I had organized at the Cesena Savings Bank. As soon as he finished, we left for Cesena.”

Now he was there to speak about the things that were most important to him, and he could not let tiredness stop him. He had never let tiredness be an obstacle; he did not allow it to impose limits on his need to live reality, all of reality, intensely. The three surgical interventions of that day had been, as always, only a part of the thousand things he had to do. In the morning, he had probably read the editorial by Biagi, just as he had read and analyzed all the other stories of the world that he followed with maniacal attention. He had been updated on the war in Kosovo, which had turned for the worse and seemed now headed toward an open conflict between NATO and Slobodan Milošević. He had discussed this with some friends, as he discussed everything, lighting and waving a Tuscan cigar in the air. And for the whole rest of the day, between one abdominal operation and another, he had called a dozen people, discussing the problems and joys of many for whom he was a point of reference. He had called Fiorisa at home in Modena to know how she and the kids were doing. He had harassed the doctors of his team at Sant’Orsola in order to have updated details on every single patient. He had prepared his notes for a talk he would give the next day in Lecce, on Saturday.

A normal day, like so many others. Everything moving according to this rhythm.

And now, gesturing with his surgeon’s hands, raising his voice, nervously pushing up the sleeves of his shirt, unhooking the leather band of his watch from his left wrist to put it on the table, Enzo Piccinini wanted to say to everyone, one more time, why he lived like this: “The problem is the unity of my life. How can my life remain unified between home and hospital, with my wife, with the people who love me, and with those who hate me? How can all this be unified with the mornings when I go to work and find an environment so tense that it makes me sick just to see it? Or with certain injustices that you can experience from the institution and from your colleagues? How does my life remain unified? This is the most important point for each of us, in times of sickness and in times of health. How can life remain unified; how can it all be one?”

His hands now framed the point he wanted to underline. His voice rose. There was no longer any shadow of tiredness; even the usual furrow in his forehead, between his eyes, was lifted by his passion and by the need to underline the importance of those words that trembled to come out of him: “The unity of life is the most important thing in the world. We cannot be divided. We cannot be fractured. Life is not a mosaic of situations. But how is it possible for life to be united with its irrepressible desire for happiness? Here is the phrase that I will always use, that I will never stop using: life is unified if we put our heart into what we do.”

There, he had said it: “Life is unified if we put our heart into what we do”—a phrase that explained everything he had said before, from when he sat down in the conference hall almost an hour late because he had put his heart into an operation, rather than just doing his job. Moreover, he could say it only in light of the experience he had lived. It could not be a theory. There were behind this phrase innumerable days like that day, lived without wasting a moment. There was the work he had done on himself, without excuses and without ever pulling back. There was the whole road he had traveled, an untiring search that began long before, from his family’s Catholic education, which he left for Marx and the extreme left, and which he then found again. It was a path of life that could have ended in a violent existence in the shadows, as had happened to some of those with whom he had crossed paths. Instead: anything but shadows! He had become a witness in the full light of the sun, armed only with words. There was a whole life behind that phrase. There were the faces of thousands of friends. There were forty-eight years lived without ever letting that heart of which he spoke rest.

There was also the promise and expectation of what would come later. Only one thing Enzo did not know that evening: he only had seventy-five days left to live. Days that were full and intense, like the one that was now ending in Cesena.

If he had known about his end, he would have insisted on the same fundamental points he had spoken about for years and that, in the last months, were charged with an urgency that maybe he did not know how to explain. They were in large part the things about which he had spoken three months earlier at Rimini, to some thousand university students connected to the experience of Communion and Liberation (CL), in a talk that—even this he could not have known—ten, twenty years later would continue to travel the world on YouTube, with subtitles in multiple languages. Now he was speaking about these things to adults in his professional environment. Because what was true—he was convinced of this—is true always, at any age. And in the following anecdote, it clearly came from first-hand experience.

“The first example I give is always the story of how I started my profession,” Enzo began that night in Cesena. “Having finished medical school, I did not know what to do. I had some idea about becoming a surgeon, but I did not really know, so I went around to all the surgeons that were at the university, and in the end, I chose (I was alone, I did not have that many options) the one I liked most, without considering whether he was the best or not. With the judgment I had later, I understood that it would have been better to use other criteria, at least to compare as many surgeons as possible. This man was the surgeon that I liked the most because it seemed to me that he was who he said he was. So, I followed him and, as young people do, I was extremely enthusiastic about my teacher and copied him in everything; I imitated him, so much so that he had a tic, and I also started to have a tic!”

Laughter. Applause. Even the kids at Rimini had laughed and applauded, recognizing themselves in that description.

“I was totally passionate about following him. I watched how he tied his shoes, how he treated people, and in the end, I realized that I was also doing these things, and it was right, from a certain point of view. Then one day, we had a meeting at the university that was really important to me; it was kind of like this meeting tonight, talking about personal experience. I had invited my professor, but I didn’t think he would come. And instead, he came. So, in the middle of a group of kids, there was this guy with his bald head. I remember still that when I saw him walk in, I thought: ‘This will ruin my career.’ I took courage and started to speak with a command I had never had: I weighed my words, I didn’t use foul language, and at the same time, I always had an eye on the attitude of my professor to understand if I was winning him over or not. And he was unmoved. When the meeting was over, he gets up to leave. I meet him at the exit and ask him: ‘Professor, how did it go?’ And he, always with the same expression, looks at me and says: ‘Piccinini, these things are for kids; these are things that kids do. I have lived so many years. I have had to make compromises; everything is a compromise. It’s good for you kids to talk like this, but then reality changes things, and in time even you will have to make compromises like me.’ The myth was over . . . and I even lost the tic!”

More laughter, a little sadder this time. It was time for the first punch. The tiredness of three surgeries and the long day of work had evaporated. He was landing on what was, for him, the most valuable thing in life. Enzo was entering “the game.” After all, soccer had been for him, since his high school days, something about which he did not compromise. At the testimony he gave in Rimini that December, he had shown up for those thousands of students with a black eye, which he got a few hours earlier on the soccer field, in a contest you could not call “a little game among friends.” Every time he was on the field, the climate was that of the Champions League final.

“It is impossible for something true to be true only at a certain age,” Enzo exclaimed, starting to raise his voice. “What is true, truth, whatever it may be, in whatever form it presents itself, always has an accent that arrives directly to the heart. Then one may or may not manage to engage seriously with that thing. The truth always hits you, but, in the measure you make space for it, the truth can cause trouble; it changes your life. And so you might search for something that doesn’t involve you too much. What remains clear is that the truth always reaches our hearts and minds, our freedom. That day I realized for the first time that there is a way in our job to abdicate our human sensibility, our sensibility for the truth, and it is dramatic because we lose the will to fight, to discover, to learn; we become ‘hirelings’ in a place where our job is only frustration.”

Some were squirming in their chairs. Doctors and nurses in that room felt all the provocation of those words. They were trying to compare their own experience with what Enzo was saying. But the speaker went on implacably.

“The second example I want to relate,” he went on, “has to do with the day that they invited me to a large hospital in Bari to tell them about how I organize my surgery unit, what I was doing with my assistants, the nurses, the clinic. It was the ‘Day of the Sick Person.’ I spoke to them with energy, explaining why I was doing certain things, what I was saying, the two meetings a week in which I teach patiently about questions of method and how to relate to the sick person. I spoke about organization, about our group, about authority understood as a point of reference. At the end of my talk, someone gets up and asks me where I learned these things. For sure, I had been to America, to England, but I had to be clear, and so in front of that enormous crowd of head physicians and surgeons, I said: ‘I understand that this will raise a lot of perplexed eyebrows, but I will say it anyway: a certain Father Luigi Giussani taught me how to be a surgeon.’ Imagine an audience like that, the murmurs.”

A certain murmur also rose in the hall in Cesena.

“Father Giussani,” continued Enzo, “did not teach me how to make incisions or certain techniques; those things I had already learned. He taught me a human position that makes the technique, the sick person, what I do with myself, become important and definitive. For this reason, now, because of how I am, I can say that, professionally, I have a way of doing things with a spirit that I rarely see in others. I don’t say it out of vanity. It is not at all due to my merit: I found myself caught up in this adventure.”

Enzo, like always, spoke about the episodes that supported what he was saying. Then he passed on to the third point. The crowd was still trying to come to terms with the first two, but by now, he was sailing on open waters.

“One day, teaching a lesson to my students,” he continued, “I ambushed them. I brought them into my office, put myself in front of them, and asked: ‘Why are you studying medicine?’ They looked at me as if they had never thought about it: they were in their sixth year! Soon the most banal answers started coming out: my father studied it, I read this book. . . . Then from the back, someone spoke up: ‘Excuse me, professor, we are here for class. If you want to keep talking about these philosophical questions, tell us, so we can go home.’ I had to teach the class. There was no other choice. I could not choose to talk about these other things. Do you understand? It was the censure of any question of meaning, of any sense of the purpose in their sixth year of medical school, when we are touching on things that sooner or later are a license to kill. The fact that someone does not ask why he is doing it is a total disaster. That someone does not answer to anything or anyone about what he is doing is a total disaster. I realized how important it is to give young people a formation, as I was given, where we ask this question, which also determines how the instruments given to us should be used. The sense of the purpose determines the instruments you use (and I use many of them) and the decisions you have to make: ‘I stop here’ or ‘I go ahead.’”

This was a choice that Enzo had to make continually. He had made it a few hours earlier, in front of the cysts of his patient. “Otherwise, what determines our decisions? Of course, you decide about your whole life, about your family, about everything. But in the hospital, it is even more decisive, moment by moment: to respond to nothing and no one is truly a dramatic, absurd formula.”

A brief pause. A sip of water. Memories of friendly faces, of companions on the journey. Twenty years in continual movement from Bologna out to the world, always trying to return home to sleep in Modena in the evening, where Fiorisa and the kids were waiting for him, but without ever pulling back from requests, challenges, pain. “Thinking about myself,” Enzo went on, his voice now a little lower, “there are a few things that really strike me. I am always around sickness, around sick people, around pain and death. This is the normal expression of man’s limitation. Sickness, suffering, pain, and death are the normal, acute expression of man’s limit, of the fact that man is limited and that this can never be removed from the awareness of our life.”

His hands start moving again, and he raises his voice, almost to a shout.

“That I will ‘croak’ is a truth; that you will ‘croak’ is a truth! The awareness of this brings with it a seriousness toward life. It is the awareness that life has its limit, and if this limit enters into the normal consciousness of our relationships, it quickly creates a capacity for a relationship that is otherwise impossible. It is the sense of limit that puts you in front of another person, immediately together, even if one has different ideas, even if one does not understand, even if one doesn’t even look at you. Because, like them, you too are needy, and in order to be yourself, you must be aware of your need. Sickness, pain, and death are the signs that remind me the most that man has a limit and that we cannot live life without this awareness. It would seem a strange condemnation, but when it is taken seriously in relationships, it immediately creates an openness and a capacity for relationships that are otherwise impossible.”

Someone turned over the invitation flyer for that evening. He reread the title: “The patient. A person first.” Whoever thought that he would be attending a debate on local health facilities and hospital policy felt out of sorts, surprised, but undeniably curious about that surgeon from Sant’Orsola whom he had heard was “a bit peculiar.”

Enzo knew what he was getting into, he imagined questions and objections, but he did not relent one millimeter. He wanted to remain with what truly counted. “If I look at you and feel the effect of what I’ve said,” he went on, “I understand that we are here together not because we all think in the same way but because we are all needy in the same way. Putting these things front and center when we go to work and when we are with our patients is decisive. What incredible patience is born from it! What incredible capacity for continual renewal is born!”

Now he was shouting, and he had that tone of voice, those gestures, that inflection, those pauses that he had learned by osmosis from Father Giussani, watching him speak, imitating him like that kid who watched and imitated his earlier teacher, the one who had then let him down. Enzo had spent his life looking for teachers from whom he could learn to be an ever-better surgeon. But the one who truly taught him a method, as he said, was that priest from Brianza.

“We do not need to theorize about serving the sick person. We do it for real! Precisely because this is the Christian sense of life and because for me, ‘Christian’ means ‘human,’ I am a part of Christianity. Otherwise, I would have nothing to do with Christianity, and it is not like I didn’t have other options. If I chose this style of life, it is because I have seen that it fits.”

For this reason, Christians invented hospitals, Enzo recalled. Because they had this sense of sickness and pain as the normal limits of life and decided to take them on. “Hospitals,” he emphasized to the room full of doctors and nurses who spent their days fighting against death, “were born not so much to heal people as to assist the incurable. Not those who delight us when they get better, but those who need to be accompanied toward death.

“Why? Because Christians do not fear the limit, and precisely for this reason, they share it and carry it with the sick. It is striking how in our hospitals, instead, this thing is done away with. The Christian is not scandalized by the limit but embraces it, and in fact, the question of the incurable is what moves us most, and one takes these people to heart.”

Now everyone was convinced that this was a Friday unlike any other in their life. Maybe unlike any other day. A Friday that they would remember always, in their department, in the operating room, at home with their family. Above all, in the most difficult moments, when they needed to find meaning in the things that beat them down. Enzo had brought them far from the comfort zone of medicine onto terrain that during medical school everyone tried to avoid.

Enzo did not dodge even one step on that terrain: “My problem is not to help the people that I see dying. My problem is to live with the awareness that death exists.

“I remember someone who came to me, who had already been operated on for pancreatic cancer in another hospital. An incredibly tough man. His daughter asked me to operate. We had to remove the entire pancreas, a very dangerous surgery. I had summoned the patient and told him. He agreed, and I told him to go home, to make out his will, and then return. And I added: ‘I want you to know something: from now on, I will be with you, whatever happens.’ He lived for another eight months, but at least he did not die with the pain of the pancreatic cancer. I kept visiting him at home until the very end, and at the end, his wife and children asked me to tell him what to expect. I told him: ‘Listen, things have gotten really complicated; anything can happen from one moment to the next. You need to be prepared.’ He looked at me angrily at first, then he was moved and said: ‘You see, we are like those drops on the window. While there is a line, life holds us up; then, when the line breaks, we are done.’ I answered him: ‘There is only one thing that holds that line: it is the One who loves us; and returning to Him is not so bad. But you may do as you wish.’ He started to cry, then he went to Confession and Communion and died two or three days later.”

A pause.

“We have to live in the awareness that death exists and take the one who is in front of us to heart. Because there is nothing more devastating than one who has cancer and is unable to have a human experience in his situation. It is a disaster to not have this human experience, and there is nothing today more devastating than this.”

To take to heart that experience—to face not just the disease but also the sick person and their family—to stand in front of them as human beings. In short, the opposite of what many of those present were taught. “We have a responsibility in this; we cannot just be ‘hirelings.’ Impossible! Doing our job seriously means answering to someone or something for what we do, not just what we feel.”

From this come the questions about what is most pressing in the morning when we go to work. Here questions emerge about how to live an experience that is not fragmented between home, love, work, and rest. Enzo continued to insist on this question, that evening and always: the unity of the person, which requires us to put our heart into everything we do. But that was not enough. It did not end there, with an exhortation.

“In order to do this, we need something greater than ourselves in life to which we can respond. Otherwise, we end up weighing what we do or do not get, the outcome of our work, and this kills the desire for happiness. We need something greater, something with which even the situations that we do not understand take on a meaning. We need something greater, when you must admit that you don’t understand, when things go the way you don’t want them to go. We need something greater in order to be free. Life is not in our hands. I do not make myself; I recognize that there is something greater, and I begin to admit that maybe I cannot understand, but that even what doesn’t go my way has a meaning.”

But even that is not enough. Because you could put your heart into what you do and have the awareness of something greater accompanying you, but then you are there in the ward with that terminal patient, and it isn’t enough. It is not enough. Even the best-intentioned and the most inspired person could hold out a little, but then he would crumble. Enzo knew it—he had had first-hand experience of this too—he had understood it, and he repeated it wherever he went, even that evening in Cesena, what else he needed: “It is the final requirement: we need to not be alone.”

It was late; he still had to eat dinner with some friends in Cesena and then set off for home in Modena. It was time to conclude, but he could not cut it short; he could not jump over the decisive step.

“We need something to support us. Without a belonging, that is, without something to which we can refer and for which your ‘I’ is not only a scattered `I,’ but has a connection to faces, to people, in a history, you cannot do it. What we ultimately need is to not be alone. Doctors or not, this is the crucial point. Also, because this is the way not to lose the will to fight. And in time, little by little, I assure you that living with gusto is not denied to the one who makes a mistake. It is denied, rather, to the one who does not have a sense of the Mystery in his own life, that is, of something greater, something present, a companionship to which he can belong. A group, a true friendship.”

Anyone who knew him intuited what he was speaking about. Anyone who had met him that evening wondered what kind of human experience allowed a medical professional to put himself out there like that. Everyone watched him come down from the stage and desired that same gaze for themselves and that same kind of judgment they had just experienced.

They would keep him there for a long time, asking him questions.

They wanted to know more.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from Everything I Did I Did for Happiness: The Life of Enzo Piccinini (Seattle: Slant Books, 2023). All rights reserved.