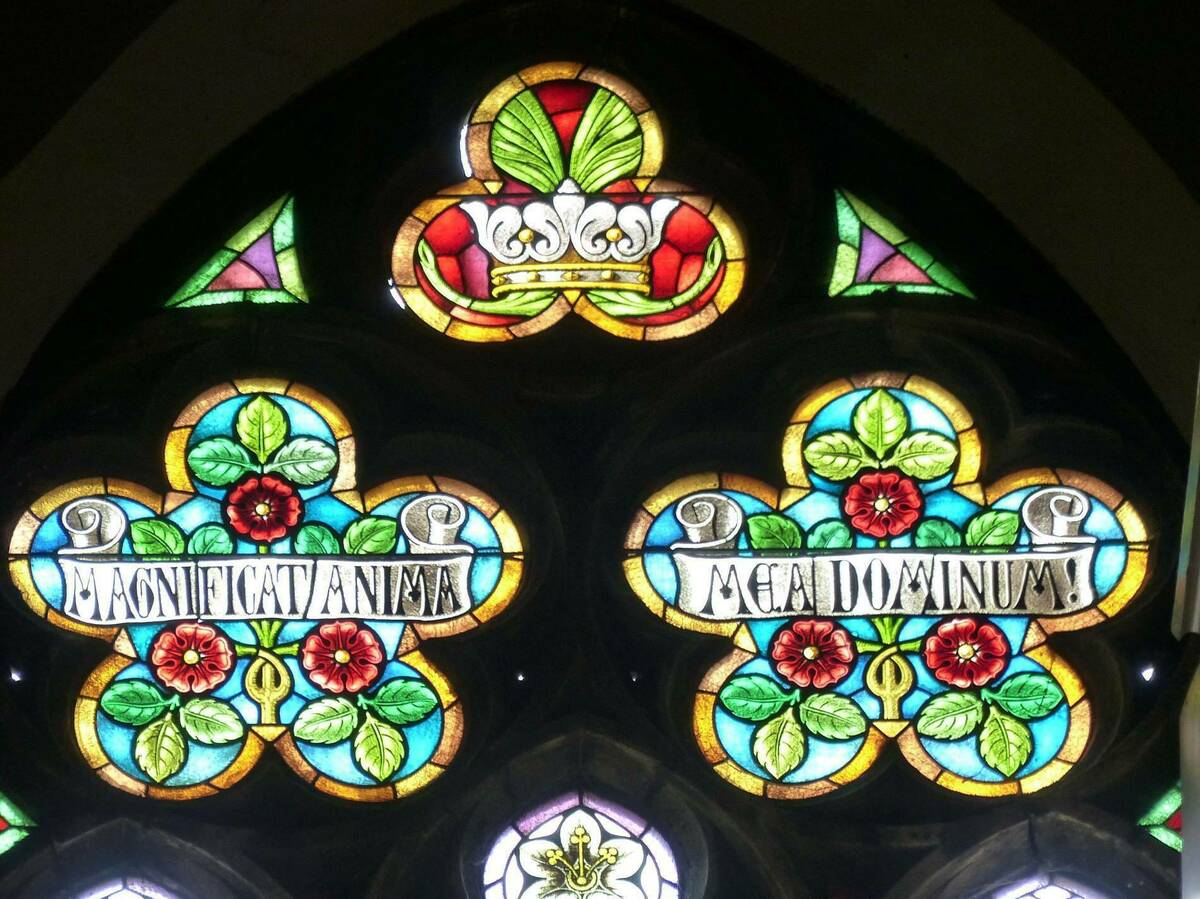

Magnificat

We know nothing about Mary’s financial circumstances, nor do they play any part in her song of rejoicing. And that is what the Magnificat really is: she is not surprised that God “has regarded the low estate of his handmaiden” but simply rejoices in the fact, since in this gesture she recognizes the God of Israel who has always acted thus.

The song that Luke puts in her mouth is primarily modeled on the song of Hannah (1 Sam 2:1–10), which speaks of practically nothing other than this inversion of earthly circumstances in which one recognizes the action that characterizes God. Where Mary sings: “He has put down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted those of low degree; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent empty away” (Luke 1:52–53), Hannah sang: “Those who were full have hired themselves out for bread, but those who were hungry have ceased to hunger. . . . He raises up the poor from the dust; he lifts the needy from the ash heap, to make them sit with princes and inherit a seat of honor” (1 Sam 2:5, 8). In her assertions, which are echoed in many other Old Testament passages, Hannah goes still further when she says: “The Lord kills and brings to life; he brings down to Sheol and raises up. The Lord makes poor and makes rich; he brings low, he also exalts” (vv. 6–7). This can make good sense in the context of the New Testament as well if one considers that God loves the poor and lowly, while “the haughty he knows from afar” (Ps 138:6), and that he had his Son descend to the realm of the dead in order from there to exalt him over all things.

It is not his justice but explicitly his mercy that Mary praises in all the reversals and inversions that God has brought about: “His mercy is on those who fear him from generation to generation,” and throughout its whole history he has adopted “his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy” (Luke 1:50, 54). If as the result of being singled out, the servant of God had puffed itself up to become one of the mighty, God’s mercy could not have been demonstrated in its case. It is only for the “low estate of his handmaiden” that “he who is mighty has done great things . . . , and holy is his name” (vv. 48–49). The poor man lying in the dust of the ash heap has no particular quality in himself that would make God raise him up: the mercy shown to him has its ground only in God himself, whose free grace finds a welcome in the emptiness of poverty while it seems it would not be needed in the overcrowded space of the rich, the high and the mighty.

In the case of Hannah—and in the whole of the Old Testament—the starting point for the elevating and liberating effect of God’s grace is first of all material, social poverty (and here, the rich and the powerful are also labeled the oppressors and the “enemies” of God, which is not the case in Mary’s song) in order to emphasize all the more the sheer dependence on God that is engendered by the powerlessness of the poor: in the case of Mary, this takes center stage.

The “low estate of his handmaiden” that God regards is the chosen place for all divinely brought about reversals in the world, the core of the divine revolution of love and its daily work of liberation. Mary is the personification of true liberation theology when she exuberantly brings to perfection the deep insight of the Old Testament, an insight made more profound in her.

“Do Whatever He Tells You”

Mary plays a mysterious role at the wedding at Cana. The couple whose wedding it was were clearly friends of the family in Nazareth: the mother was invited (her husband was presumably no longer alive) as well as her son along with his friends, who were probably regarded as his first followers. Mary is one among many other guests. But she is the first to notice the embarrassing situation these probably not very well-off people are in, and if she draws her son’s attention to it, it is certainly not because she expects him to work a miracle (hitherto he had not worked any—John 2:11) but in the hope that he would find a solution. What is to be noted here is Mary’s awareness of the needs of the poor and her instinctive sense that her son must be told about it and that he will somehow be able to provide help.

And then it is as if the whole scene has moved up to a higher plane. Jesus has begun his ministry: he is no longer this person’s son. And in his ministry he no longer sees Mary as his own mother but as “the woman,” the other, the “helpmate,” who, however, will only take on her own proper role when he finally, on the Cross, becomes the “new Adam.” She has already suffered: the sword has already pierced her soul. He, on the other hand, is only now marching toward his “hour.” Then, in complete poverty and stripped of everything, even of God, he will change the wine into his blood: the effusive response to every most audacious entreaty. The “woman” whom he tries to put off—“What have you to do with me?”—is, however, already from the start the Church, and as such she has a right to insist on her “request” (actually, just her pointing out of the people’s need). But she does it in the most wonderful way that expresses everything at the same time: her complete disinterest and surrender to his will, but also her confident hope; and it is precisely by not pushing, by her lack of self-will, that she prevails and the hour of the Cross is anticipated: not yet is wine transformed into blood, but water into wine: “Do whatever he tells you.” Perhaps nowhere is Mary’s whole disposition more present than in this saying.

“And His Mother and His Brethren Came”

In Cana we saw Mary with those who were materially poor. Here (Mark 3:31) we see her with those who are spiritually poor. These “brethren”—cousins and other close relatives, described even today by Arabs as “brothers”—are annoyed by Jesus’ extravagant behavior and think he is out of his mind. When he appears in Nazareth, they will take offense at his making himself out to be more important than his relatives: “Are not his sisters here with us?” (Mark 6:3). We have already seen that these people who did not believe in him urged him to go and take his act to Jerusalem instead: “For no man works in secret if he seeks to be known openly. If you do these things, show yourself to the world” (John 7:4).

One must imagine Mary among these people. She does not think of contradicting them or of setting herself apart from them as someone who knows better about everything. She listens to this kind of talk every day, possibly also to the reproach that she should have brought him up better and should not have put such ideas in his head. She belongs to the family. The immaculate belongs to the clan of sinners, the seat of wisdom belongs to the bottomless stupidity of humanity. One must listen to this clique of relatives discussing among themselves how they can put an end to this nonsense. Finally, they decide to send out an expedition so that they can see things for themselves, and his mother is dragged along. But they are sent packing, even when Jesus is told his mother is there. The family no longer counts for anything. It is a quite different family that matters now: those who believe and who do the will of God.

One can imagine what this company had to say to each other on the way home. Even though Mark puts the event earlier (3:21), it is quite probably at this point that the family came to the decision that he ought to be stopped for his own good. And it was not just a matter of words—words turned into actions: “His friends . . . went out to seize him, for they said, ‘he is beside himself.’” Mary was living in their midst. At what point James, one of Jesus’ brothers, came to believe in him we do not know: he became Peter’s deputy in Jerusalem when the latter had to flee from the city after being freed from prison.

Mary does not stand out from the group. She remains so inconspicuous that the synoptic Gospels do not even notice her among the devout women at the foot of the Cross. Several of them are named, but she is not. Perhaps she stands there, together with John, keeping to herself, distant from the others, lost in the crowd of Roman soldiers and of people who had come to gape and mock and the crowds streaming in and out of the city past the crosses on the day before the feast: some poor woman.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from Mary for Today, courtesy of Ignatius Press, All Rights Reserved.