As we start the month of November, my family is enjoying the panoply of fall colors, football games, and searching for the local harvests of apples and pumpkins. However this joy is tempered by the thought of the coming bleak Michigan winter. A bittersweet sensation accompanies this season that contrasts the fullness of harvest and bonfires with friends with the impending silence and darkness. At this time in the liturgical year, the Church asks us to meditate in a particular way on the four last things: death, judgment, heaven, and hell. We ready ourselves for our own death and attend more carefully to the souls of the dead. These are fitting themes for the preparatory and penitential season of Advent.

In practicing our faith in a full-blooded liturgical way, we can refute the Nietzschean charge that Christianity is a morbid world-denying religion. Since the Church grafts natural symbolism into eschatological realities, our faith should be understood as an attempt to heal the world from the curse with which we inflicted it. Our goal is not to escape the world, but to tend the scattered seeds of the logos that they may produce a full spiritual harvest.

The late Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling discerned this inner connection between the changing of seasons, Catholic liturgy, and eschatology. In his novel Clara a character notes of All Soul’s Day,

How meaningful it is that the graves should be decorated with species that are late flowering: isn’t it fitting that these autumn flowers should be consecrated to the dead, who hand us cheerful flowers from their dark chambers in spring as the eternal witness to the continuation of life and to the eternal resurrection?

Thus, ahead of All Soul’s Day then, we will explore 1) how Sacred Scripture relates nature to eschatology 2) a medieval conception of how the dead continue to linger and 3) how Friedrich Schelling can help form a Catholic understanding of the previous two themes to counter modern disenchantment.

The Harvest of the World

It seems that agricultural images are always close at hand when either Christ or St. Paul speak of death paired with resurrection (as opposed to, say, the abundance of pastoral imagery in other contexts like death paired with the final judgment). For example:

Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit (John 12:24).

And:

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive. But each in his own order: Christ the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ (1 Cor. 15:20-23).

Why employ the fruits of the earth as the analogy for resurrection rather than animal sacrifice? Obviously, Christ’s Johannine titles “the lamb of God” and “the lamb who was slain” warn us away from making any absolute distinction. But there does seem to be something especially fitting about seasonal and diurnal cycles and their relation to agricultural production for figuring forth the life of the world to come.

Pope St. Clement of Rome (whose feast day is in November) had already discerned this in his Letter to the Corinthians—one of the first extant writings of ancient Christianity:

Let us consider, beloved, how the Lord continually proves to us that there shall be a future resurrection, of which He has rendered the Lord Jesus Christ the first-fruits by raising Him from the dead. Let us contemplate, beloved, the resurrection which is at all times taking place. Day and night declare to us a resurrection. The night sinks to sleep, and the day arises; the day [again] departs, and the night comes on. Let us behold the fruits [of the earth], how the sowing of grain takes place. The sower goes forth, and casts it into the ground, and the seed being thus scattered, though dry and naked when it fell upon the earth, is gradually dissolved. Then out of its dissolution the mighty power of the providence of the Lord raises it up again, and from one seed many arise and bring forth fruit (§24).

Read spiritually—that is through the life, passion, and death of Jesus Christ—the book of nature functions in a way similar to the Old Testament. The economy of redemption is prefigured in the order of creation and the utterly simple divine will draws multiple temporal events and finite structures into a single providential governance. Or, to put it another way, the author of Scripture and the author of Nature are one and the same, and God is most manifest when we acknowledge the permeable membrane of symbols and imagery that constitute the written and unwritten divine works.

In this vein, no passage of Scripture reveals more clearly how our destiny is knitted together with the destiny of the world more than Romans 8:18-23:

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies.

Humanity (individually and as a whole) is a microcosm of nature, containing all her elements representatively within itself. Even further, nature will escape her cycles of death and decay, pain, and necessity, only through the final victory of divinized humanity. As the effulgence of divine light courses through our redeemed bodies, we will participate in transfiguring the world and help reveal the New Heavens and the New Earth. For now, all of nature sleeps fitfully, but it is dreaming of resurrection.

The Lingering Dead

Though not explicitly one of the four last things, the mystery of the communion of saints is the practical and theoretical ground for all of them. Without the existing community of the Church, we do not approach Christ, and it is in recognizing and venerating the saints of God that we participate most fully in the historical memory of his resurrection. The Catholic doctrine of Purgatory and prayers for the dead impresses forcefully on us the communal nature of the four last things and the constant interchange between the living and the dead. If scripture and creation can be said to have a permeable membrane, how much more must our present life and the life of the world to come be intertwined? What could be more intertwined than the many members of Christ’s Mystical Body?

The official saints of the Church form a kind of exemplary backbone and continuous resource for piety and theology, but this is not at the expense of the ordinary faithful who are the object of ecclesial urgency. We are all related in ways that break down the barriers between the mundane and the supernatural. The variegated (and sometimes strange to our ears) history of the Church bears witness to this fact. Besides the explicitly hagiographical texts of medieval literature, various vitae and miracula contain stories where ordinary Christians appear after death for the purpose of moral/theological education or, more commonly, to ask for prayers. Peter the Venerable’s work De miraculis includes several such hauntings. This genre is arguably present in pious Christian literature as early as The Passion of Felicity and Perpetua, where Perpetua sees in a vision her dead unbaptized brother enjoying the delights of Paradise.

St. Augustine was famously skeptical of shades appearing after death, but not so his later admirer, Pope St. Gregory the Great. Book 4 of his highly influential Dialogues contains two particularly vivid ghost stories related to the reality of Purgatory. The first story, recounts that a certain deacon named Paschasius had supported a schismatic candidate (despite his own personal piety). Some time later a bishop named Germanus entered the local baths and found the dead Paschasius working there as an attendant:

At which sight being much afraid, he demanded what so worthy a man as he was did in that place: to whom Paschasius returned this answer: “For no other cause,” quoth he, “am I appointed to this place of punishment, but for that I took part with Lawrence against Symmachus: and therefore I beseech you to pray unto our Lord for me, and by this token shall you know that your prayers be heard, if, at your coming again, you find me not here.” Upon this, the holy man Germanus betook himself to his devotions, and after a few days he went again to the same baths, but found not Paschasius there: for seeing his fault proceeded not of malice, but of ignorance, he might after death be purged from that sin. And yet we must withal think that the plentiful alms which he bestowed in this life, obtained favour at God's hands, that he might then deserve pardon, when he could work nothing at all for himself.

St. Gregory the Great relates another story where a certain pious priest would go to the baths and be waited upon by a mysterious man he had never met. After this happened several times, the priest wished to thank his attendant and brought along some blessed (but unconsecrated) bread. However, when presented with the present the unknown man looked pained.

“Why do you give me these, father? This is holy bread, and I cannot eat of it, for I, whom you see here, was sometime lord of these baths, and am now after my death appointed for my sins to this place: but if you desire to pleasure me, offer this bread unto almighty God, and be an intercessor for my sins: and by this shall you know that your prayers be heard, if at your next coming you find me not here.” And as he was speaking these words, he vanished out of his sight: so that he, which before seemed to be a man, shewed by that manner of departure that he was a spirit. The good Priest all the week following gave himself to tears for him, and daily offered up the holy sacrifice: and afterward returning to the bath, found him not there: whereby it appeareth what great profit the souls receive by the sacrifice of the holy oblation, seeing the spirits of them that be dead desire it of the living, and give certain tokens to let us understand how that by means thereof they have received absolution.

Not only do St. Gregory and later accounts of the Miracula genre affirm that the dead are able to linger among the living, in presenting these peculiar narratives we learn that specific places and personal relationships are constitutive of these lingerings. Ghosts appear somewhere and to someone for specific (if uncanny) reasons. In the liturgy, we pray for the souls of the faithful departed in a general and official way. But each and every soul is marked with reference to its history, its locale, and its dispossessed body. The same principle of sacramental logic that allows for local cults of saints and particular patronages and pilgrimages extends to all of those who are now dead. Though, of course, the dead are never really dead since our God is the God of the living.

Friedrich Schelling’s Clara

The intuitive sacramental connection between eschatology, the natural world, and the communion of saints, now seems like a half-forgotten dream or something that could only be viewed as a curiosity of historical record. Perhaps once intelligent men like Gregory could consider Christ, sin, sacraments, and even ghosts with credulity but not now. The pale light of a decaying Alexandria and Rome could sustain such imaginings, but surely they dissipate in the harsh fluorescence of the modern world. We have created for ourselves permanent artificial suns and have no more need of nocturnal fantasies.

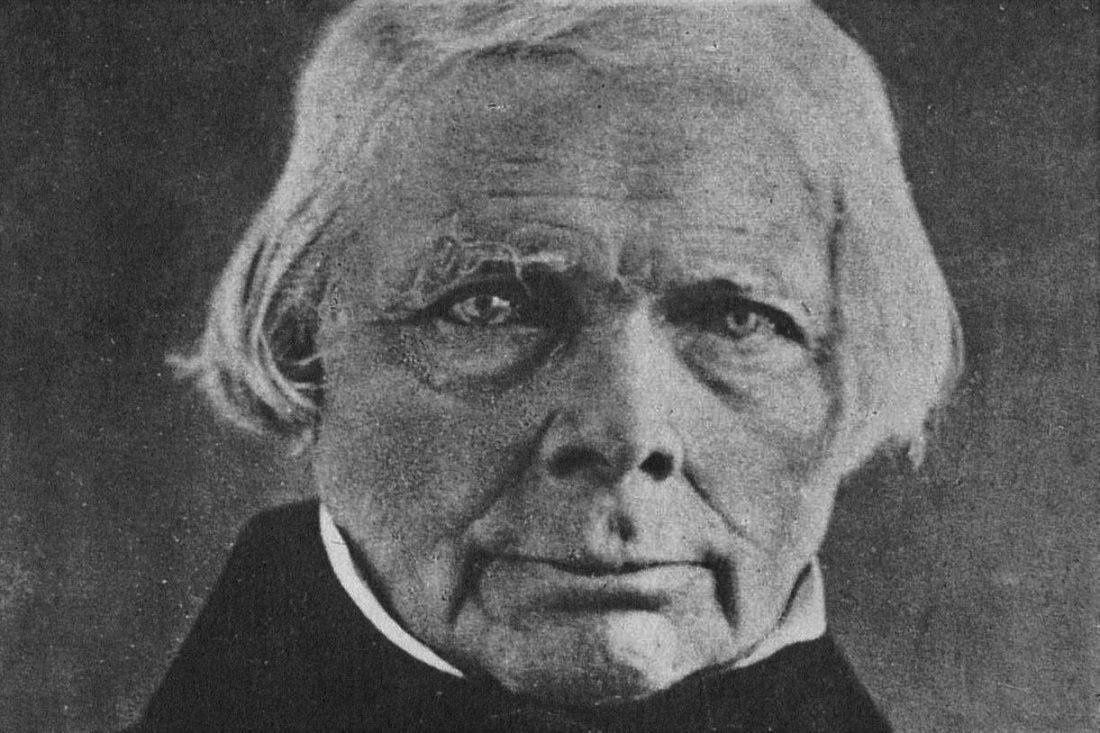

In his 1810 philosophical dialogue Clara, Friedrich Schelling sought to rehabilitate those intuitions and affirm the authenticity of their religious origins after the varied challenges of Protestant critique, rationalist Kantian restrictions, and eliminative materialism. Schelling himself never rejected his religious background as the son of a Lutheran pastor though he was accused of being a crypto-Catholic on personal and intellectual grounds. His Lutheranism was not primarily that of Melanchthon or even Luther himself. Neither did he settle comfortably into the denuded Lutheranism of Kant. Schelling’s Lutheranism (if we may call it that) was more indebted to German Pietism, the wild and eschatological mysticism of Oetinger and Benger. Schelling’s unique spiritual and intellectual path primed him to resist both the rationalist Kantian foreclosure of eschatology and the literal closure of monasteries and suppression of folk Catholicism taking place in Germany during his life. All of this was folded into his delicate and evocative work Clara.

While the subtitle of the dialogue “On Nature’s Connection with the Spirit-World” is vague, one only has to read the first page to be convinced that Schelling is most definitely not offering us a syncretic spiritualist cocktail. Not only is frequent recourse made to scripture and to theological ideas of a distinctively Christian provenance, the ritual and liturgical practices of the common faithful ground the entire conversation. The eponymous Clara has recently suffered the death of a loved one and is visited by several friends who wish to comfort her including a doctor, a priest, and a clergyman. The narrative starts in November with Clara’s friends and interlocutors coming into the (Catholic) village where she lives and observing how the locals observe All Souls’ Day. The priest narrates how the graves “illuminated by the Autumn sun” are covered in flowers and how all the townspeople have gathered to grieve and remember those they have lost. The priest comments:

How moving this custom is, my companion said, and how meaningful it is that the graves should be decorated with species that are late flowering: isn’t it fitting that these autumn flowers should be consecrated to the dead, who hand us cheerful flowers from their dark chambers in spring as the eternal witness to the continuation of life and to the eternal resurrection.

Whether through an explicit debt to the patristics or by some wise inspiration, Schelling discerned the same inner continuity between the cycles of nature and the resurrection as Pope St. Clement of Rome. The different chapters of the dialogue are very careful to accent the changing of seasons, the shifting of day to night, and liturgical celebrations like All Souls’ Day, Christmas, and Easter. Some things, says one of the interlocutors, can only be expressed at night.

Against the clergyman (a separate character from the priest) Clara makes many passionate appeals for trespassing the narrow confines of Kantian conscience and its limited horizons. The spiritual world in all its fullness includes not just God, but entire legions of angels, coursing multitudes of saints, and innumerable souls in transitus that still relate to our world right now. And while we must always eschew any intention of utilitarian control, the nexus between this life and the life of the world to come is open and ever-full of spiritual commerce. There is a lively exchange of goods between the temporal and eternal at all times and any account of the world which discounts this will suffer accordingly.

The fifth and final chapter of the novel also features an explicitly Catholic practice as the verification for Schelling’s philosophical insights. Clara and the priest encounter a Protestant woman placing money into the offering box of a Catholic church who proceeds to explain herself by telling them a story. Her son had fallen ill, and with him on the verge of death, she became desperate enough to follow the advice of a Catholic neighbor to pray to the local patron saint, Walderich, for help. Though held back by the idea that because God had no need for mediation, this would be a questionable act, she finally relented and made a vow to St. Walderich for the sake of her son. He was miraculously healed and accordingly she came to express her gratitude by fulfilling her vow.

This spurs a conversation between Clara and the doctor on the fittingness of spiritual locality:

“But,” Clara said, “shouldn’t it really be assumed that . . . through spirits having been shown a certain respect in particular locations for a long time, that they really do become the protective spirits of those areas? Isn’t it natural that those who first brought the light of belief into these woods . . . that they also continue to share in the fates of the countries and of the peoples, both of which having been built through them and become united in one belief?”

The doctor points out that even the ancient oracles of Delphi and Delos were associated with particular places and asks “shouldn’t we draw the general conclusion from this that locality isn’t as irrelevant to the higher as is generally supposed. Indeed, don’t we feel a certain spiritual presence in every place, which either attracts us to that place or puts us off?” Schelling is not arguing against the universality of Christian belief and practice or denying Christ’s words that “there will come a time when you will worship neither on this mountain nor that but in Spirit and in truth.” Rather, he is saying that within the universality of Christ’s incarnational mission, locality and finite mediation are still significant and worthy of honor. And he is defending this essentially Catholic point of liturgical sacramentalism a nineteenth century post-Kantian Lutheran.

Conclusion

Nietzsche, another, and doubtless very different, Lutheran pastor’s son, has his Zarathustra fulminate against churches by mingling the images of an occluded nature with an oppressed conscience. He asks:

Who created for themselves such caves and penitence-stairs? Was it not those who sought to conceal themselves, and were ashamed under the clear sky?

And only when the clear sky looketh again through ruined roofs, and down upon grass and red poppies on ruined walls—will I again turn my heart to the seats of this God.

Against this Nietzschean framing of nature, human or otherwise, as offering an alternative to a sacramental economy, we can offer the Church and her liturgy as the only remedy for a wounded cosmos. It is when we are open to the divine that we are truly open to nature’s needs and deepest aspirations. Schelling noted that even flowers “spiritualize” as they release sweet invisible fragrance from their more visibly material blossoms. The refusal of an ecclesia simultaneously visible and invisible, composed of earthly members and those who have crossed the threshold of mortality, is to wrongly hypostasize nature as it is instead of recognizing what it should be-what it desires to be.

The interior of Notre Dame’s basilica of the Sacred Heart beautifully depicts this Catholic understanding of simultaneity. Like horizontal ladder of Jacob, it is populated with saints, prophets, and angels in an expanse that is both earthly and heavenly. Within and beyond the stars, the wise and holy creatures shine with glory. It proves without words that nature is only herself when she yearns to join her present beauty with the glory of the world to come. After all, the threshold of a Church is in Henry Adam’s apposite description a pons seclorum.

The faithful departed, both those fully beholding God and those still being purified, constitute a broad avenue of two-way traffic between now and then. Many churches include cemetery grounds (or at least have them nearby) for this very reason. Even those without include some fragment or bone of a saint underneath the altar in order to symbolize and effect this union. Like lodestones, holy relics draw all flesh and spirit toward heaven with a kind of holy magnetism. Only the sacramental and liturgical furnace of Christ’s Mystical Body can forge an immortal diamond from Nature’s Heraclitean fire.