Simeon the Stylite, famed for standing on a pillar for over 30 years in the middle of the 5th century, is something of a joke for moderns. He has been deemed irrelevant, self-flagellating, and bizarre. For example, Edward Gibbon, in his famous Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, writes the following about Simeon’s life:

A prince, who should capriciously inflict such tortures, would be deemed a tyrant; but it would surpass the power of a tyrant to impose a long and miserable existence on the reluctant victims of his cruelty . . . a cruel, unfeeling temper has distinguished the monks of every age and country: their stern indifference, which is seldom mollified by personal friendship, is inflamed by religious hatred; and their merciless zeal has strenuously administered the holy office of the Inquisition.

Even the much more favorably disposed St. Francis de Sales puts Simeon in the category of saints whose lives have “more material for us to marvel at than to imitate.”[1] So what of this curious saint? Is he just an oddity of ages past, at best a sort of unicorn among saints, whose only purpose was to dazzle us for a brief moment and at worst a holier-than-thou voluntary martyr who set a precedent for every sort of religious cruelty, as Gibbon supposes?

The historical records of his life and cult point us in a very different direction. First of all, unlike some saints of late antiquity, Simeon’s life is on historically solid ground. Of the three written accounts of his life which come down to us, two of them are written by his contemporaries (Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Antonius), both of whom saw Simeon while he was alive. Antonius knew the saint well. Simeon really did stand on that pillar, and bear the sufferings that came with it. Not only do we have eyewitness accounts of his sanctity, but Simeon was an extremely popular saint in his own time. According to his biographers, Simeon enjoyed worldwide fame and people from all quarters sought him out for his counsel, for his blessing and for healing. The archeological record supports this claim, as many pilgrimage tokens[2] featuring his likeness have survived dating from hundreds of years after his death, and indeed the base of his pillar stood until modern times.[3] Simeon also inspired many imitators—other stylites (such as St. Daniel the Stylite) and, even later, dendrites (those who lived in trees).

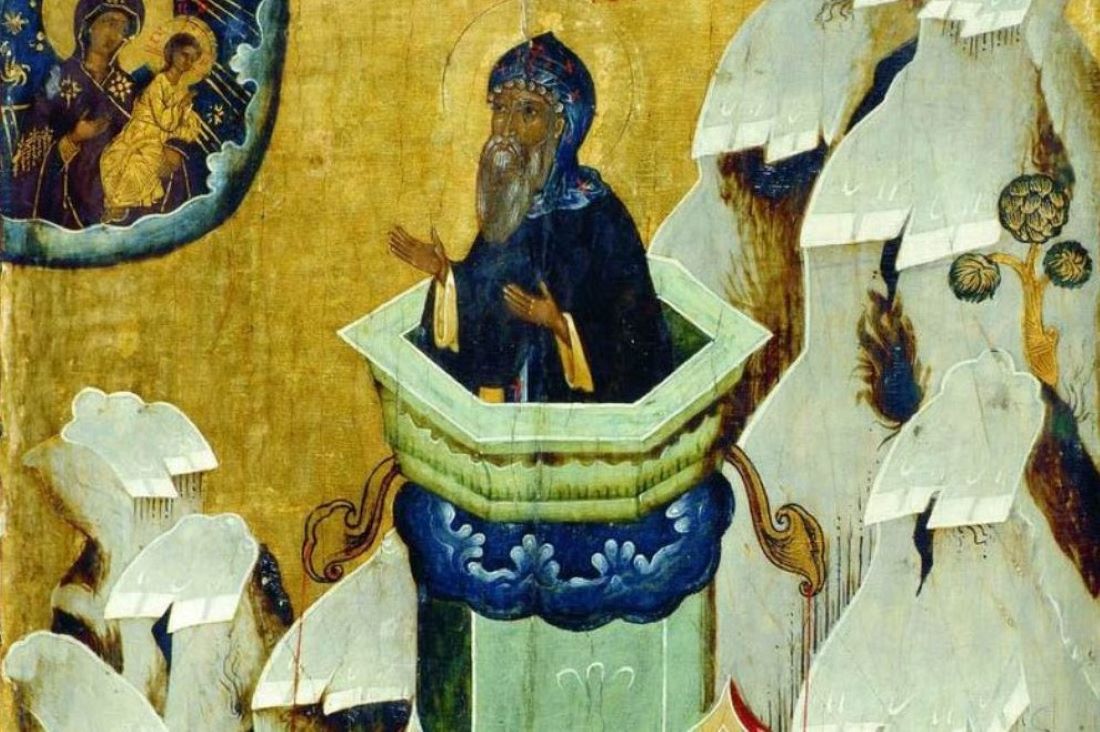

So why is Simeon such a scandal to us today? And what was he doing on top of that pillar, anyway? To understand Simeon’s exploits, we must first understand that traditionally speaking, standing is the posture of prayer (it is hard to miss this point if you have ever attended an Eastern liturgy). Simeon was a true embodiment of the monastic ideal to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thess. 5:16). Simeon’s aim in climbing the pillar was not, therefore, to be a spectacle, but to set himself apart and to commit himself to prayer and to penance with his whole body at all times. The fact that his pillar got taller and taller as time went on did serve as a striking visual reminder of the intermediary power of prayer (since Simeon was literally suspended between heaven and earth, like Christ on the cross), but it was not an act of pride or showmanship. In fact, two monks who accused Simeon of practicing a flashy and novel form of asceticism found themselves humbled when they finally beheld the saint, when they were too timid to ascend to the pillar’s treacherous height themselves.[4]

Theodoret of Cyrrhus explains the need for Simeon’s pillar in this way: just as God deigned for strange and startling signs to be manifested through his prophets (e.g. Hosea’s marriage to a prostitute, and Ezekiel laying on his side for 40 days), so God also ordained Simeon’s pillar to be a sign (perhaps even a sign of contradiction).[5] If Simeon is a scandal to us, therefore, the true scandal is that we do not believe in the power of prayer like Simeon did. To dedicate one’s whole life to the perpetual contemplation of God, to persistent supplication, to earnest self-mastery is, to us, absurd. Although Christ tells us that Mary, who sits motionless at his feet, has the better part than Martha, who busies herself with many works (cf. Lk. 10:42), do we believe it? If we do not, then Simeon is just a fanatic on a pole.

But if we understand Simeon’s life not only as one of perpetual prayer but also of sacrifice, Simeon can be adopted as the perfect saint for our modern times. What do we need more in our fast-paced, demanding, screen-filled lives than someone who achieves holiness without moving? Simeon can serve for us an icon of a saint who planted himself where God had put him and remained there, believing that God could work through the most banal circumstance, that of a man standing still, opening his heart to God.

Simeon’s life also reminds us of a very important lesson that we tend to forget: we cannot escape suffering (despite all the advances of modern science), and indeed suffering is the means of union with Christ. Simeon essentially did nothing, he did not move, he did not marry, he did not have a job and yet he suffered immensely, standing still in rain and snow, pushing his physical body to its limits. And when we, like Simeon, embrace that suffering, it can transform us. This meaning of suffering is beautifully captured by my favorite story from Simeon’s life. A “king of the Arabs,”[6] as Antonius calls him, comes to see Simeon and to ask for his prayers. Simeon has a rope tied tightly around his waist and, because it is gnawing at his flesh, maggots have taken up residence. One of these maggots falls from atop the pillar to the feet of the king.

Our initial reaction to this setup of this story is one of disgust. We want to turn away from this suffering, and from this seemingly needless penitential fervor. Our reaction to this extreme instance of suffering, however, is only an amplified version of our reaction to all suffering, of our modern tendency to disguise, bury and turn away from the harshest realities of life, and especially of death. But the pilgrim king is seeking in earnest, and he does not recoil. Seeing that something has fallen from the saint, he picks it up—and, to our surprise, he finds that what he has in his hand is not a worm, but a pearl. The king interprets this sign as one of forgiveness and blessing brought about by Simeon’s ceaseless prayer. In other words, Simeon’s suffering has been transfigured by his love of Christ into something precious; his suffering has become the pearl of great price (cf. Matt. 13:45-46).

[1] St. Francis de Sales. Introduction to the Devout Life (New York: Image, 2014), 98.

[3] The pillar is believed to have been recently destroyed or damaged by ISIS attacks in Syria.

[4] “The Life of Daniel the Stylite” in Three Byzantine Saints (Yonkers, NY: SVS, 1977), 6.

[5] “The Life of Simeon Stylites by Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus” in The Lives of Simeon Stylites, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian, 1992), 12.

[6] “The Life and Daily Mode of Living of Blessed Simeon the Stylite by Antonius” in Lives of Simeon, 18.