Our Strange Addiction

One strange feature of our current political moment is that we cling possessively to politics even as we push it away. So political life is somehow both everywhere and nowhere. At the level where politics is supposed to happen, we have tried to eliminate it because we are engaged in a neoliberal flight from politics. Neoliberalism (the remaking of everything in the image of the market) evades public deliberation and the determination of public decisions. Instead it urges governance by administration, judicial fiat, and technical expertise.

None of this is democratic politics, if by that we mean engaging in public deliberation and common decision-making. Further, neoliberalism conceives of citizens relating to their government on the model of consumers relating to markets, and this is profoundly at odds with an approach to politics understood as shared participation in the burdens and benefits of public life. Yet even as we push politics away, we cling to it. The personal has become political; everything we touch is politically fraught. This debased politics is infecting our places of work and worship, our dinner tables, our social media, our music and movies, our food and hairstyles, and our lawn signs. Like an addict who cannot get enough of something he hates, we push political life away and we cling to a debased form. Our common life is fraught with an addict’s experiences of restlessness, frustration, dissipation, and exhaustion.

Since this is so, religious believers have to think about politics in much wider horizons. We have to wrestle with our political pathologies not simply by figuring out the right policy or which party or candidate is “the most Christian.” We have to ask much more fundamental questions. If we became addicted to a career, for instance, wouldn't we need to put work in its proper place? Wouldn’t we need to figure out both why work was so compelling and what its limits are? Wouldn’t we have to wrestle with the true meaning of work by relating it to all the other facets of a flourishing life—our families, our communities, our faulty notions of “wealth,” our hobbies, our leisure, and our God? Wouldn’t we have to return to Socratic questions like, “What is work, anyway? And what does it serve?”

We need to ask the same questions about politics: What is it, anyway? And what is its place in human life? Why are we so attracted to and repelled by it? How can we restore it to its rightful place? Working through these questions together is among our most pressing political needs. We cannot keep pushing politics away. We cannot keep politicizing everything either. According to neoliberalism, political actors must not take a stand on the good life. Instead the state should defer the good. It should empower individuals by fostering what Hobbes called, “small powers” that can be used to any and all purposes.

So the neoliberal state tries to empower individuals, increasing their wealth, opportunities, and choices. The task of politics is to provide the conditions for these apparently open-ended powers, rather than try to publicly resolve questions about how people might live together. Read Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now if you want to understand the rhetoric at work . . . more: individual choices, opportunities, rights, scientific, technological and economic powers; less: poverty, ignorance, and suffering.

The problem is that political issues are always about the human good. Take any political issue almost at random and we see that it involves us in the question, “What is good for our community to be and do?” Should we allow neon signs downtown; should we decriminalize marijuana; should we teach creationism; should we go to war with Iran; should we tear down that statue of Stonewall Jackson; should we raise the tax on fur coats; should we have a waiting period for abortion; should we forbid people from buying human organs; should we grant amnesty to immigrants? All these questions involve the most important political questions: what is justice? What kind of people do we want to become? Neoliberalism tries to convince us that we can endlessly defer politics by substituting technocratic expertise or market mechanisms for common deliberation and action. Politics is reasserting itself because political questions keep coming up.

They keep coming up precisely because we are political creatures who need politics to become human together. In large part being human is a matter of figuring out what goods to pursue. Because we are social, we only achieve our humanity through shared conversations about what goods are worthy of pursuit, and how best we should pursue them. We have a host of political challenges that cannot be resolved by technical expertise, the administrative state or the judiciary. Since they are political issues they need to be resolved politically. These political challenges—race, criminal justice, war and peace, citizenship, equality, historical memory and the education of our children—require us to wrestle with fundamental questions about the human good politically. Political questions are everywhere. Genuine politics is nowhere to resolve them. Political correctness (of both the left and the right variety) rushes into the vacuum, promising that it will be able to master the questions—it knows just what justice requires, and just how to punish those who disagree.

What is at stake in all this is a rightly ordered love of political life. Truth is at stake too. Loving always involves us in truth—we cannot love anything well unless we are struggling to understand what it is. For believers, the goal is to understand what we love by the light of faith: How does our faith that this person is a creation of God inflect our understanding of who she is and the way we need to love her? So we need to situate our search for the truth about politics within the widest horizon: the horizon of faith. When Dante lost his way, he reoriented himself to his life by reorienting himself to everything else—his God, his creation and destiny; sin and redemption; heaven and hell, and Florentine politics.

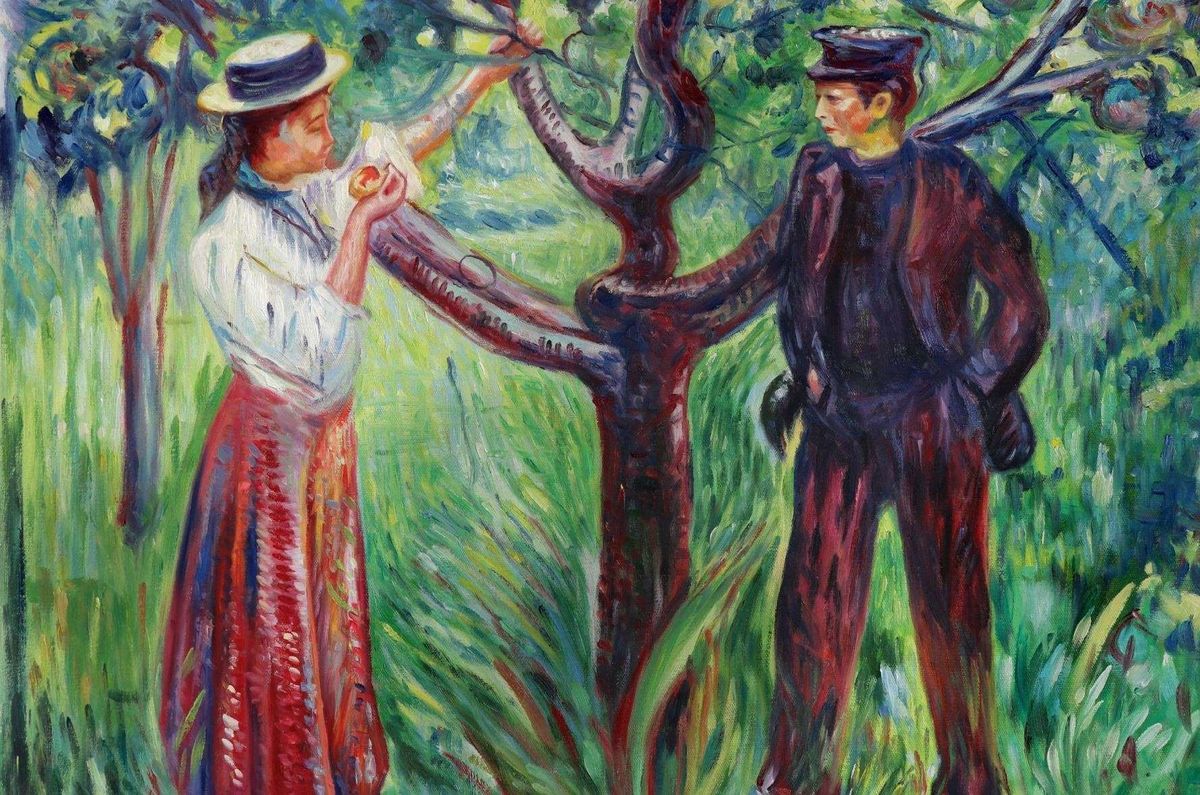

If Adam and Eve never sinned (if we still lived in Eden) would we be practicing politics? This question recurs in Christian theology because it helps us think about politics in relation to the human good. If we think that politics would not have happened without the fall, then we think that it is a concession to sin. In this view, politics is a just way of keeping our unruly desires in check. That is all it is good for. So we have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that politics is about power, competition, coercion, and manipulation. Of course, there are good reasons for thinking this way: just spend ten minutes watching FOX or MSNBC. Or spend ten minutes in a little league parent meeting. Yet if we believe that politics would have happened without the fall, we think it is essential to human perfection. I believe politics would persist in Eden because it is part of the divine plan. Our thought experiment functions the way “state of nature” theories work in liberal political thought. What does politics look like in a paradisical state of nature?

The Politics of Paradise

In our thought experiment, Adam and Eve never ate the fruit and we would not suffer from the effects of the fall, traditionally understood as weakening of the will and darkening of the intellect. Genesis says that God made everything good, and he made human beings in his image and likeness. The way we participate in creation is the way we become more ourselves. As we become more fully ourselves, this divine image becomes more like God. In the story, God speaks, he creates, he plans and orders, he evaluates (he calls things “good”), and he interacts with his creatures in a provident way.

In a like way, we become more fully alive when we participate in these divine activities in our own uniquely human way. We must speak, plan, evaluate the goodness of our actions, and interact with each other in a way that manifests loving stewardship over our many gifts—especially each other. Of course there are many possible paths to a good life. Which is best for us in this particular place and time? We have vivid experiences of human creativity, imagination, and practical wisdom becoming manifest in a variety of compelling cultural expressions – from mariachi bands or Noh theater to Gregorian chant. We need community in order to build up these distinctive goods. How come?

I will stipulate that certain features of the human condition would persist if we still lived in Eden—conditions that would help drive us to political life. The conditions God created for us make certain human kinds of cooperation both possible and necessary. Specifically, the citizens of Evopolis—a city named after our common mother—would have an interest in cooperation for common advantage across a wide range of activities: economic, political, familial, technological, and social. Different citizens would have different ideas about what was best for the community.

So they would have disagreements about how resources that are produced by this cooperation would be distributed or how to build out a town center, or how best to coordinate a farming cooperative. The disagreements would not be characterized by rancor, jealousy, nor suspicion. But still, not everyone would win. The citizens of Evopolis would have to use their capacity to reason and speak, the ability to communicate with each other to evaluate what they were accomplishing, to coordinate their activities and resolve their disagreements.

So in Eden, human beings would still be interdependent and rational. Prelapsarian people still need food, defense against the elements, and stored up technical knowledge. We would also need each other so that we could come to understand ourselves, discover who we are, and coordinate common decisions and activities. We would need to converse, working through disagreements towards a determination about decisions affecting public things. Because we would still be developmental beings, we would have to raise and educate our children and learn complex crafts.

I will also stipulate that Eden would be characterized by moderate scarcity. Genesis says that Eden is a garden, but God asked Adam and Eve to be his gardeners, implying some work still needed to be done. Given this scarcity, we would still need to trade, to specialize functions, and to divide labor, and perhaps own property. All this would happen so that we could achieve a level of sustenance and excellence across different human endeavors; we would have to agree on rules of cooperation and sharing in order to be interdependent in a flourishing way.

Citizens of Evopolis would also be rational, possessing the capacity to speak and communicate in word and deed. We should think of this ability as arising in part because human beings are underdetermined. Of course, dogs or birds are also developmental. And many species (like wolves and bees) are interdependent, engaging in complex cooperative behaviors. But our fellow animals reach their potential through a mysterious phenomenon we do not really understand called, “instinct.” Because they have instinct, other animals do not need to deliberate about how to eat, mate, or raise their offspring. However, human behaviors are not completely determined by instinct, and this lack of determination clears ground for our ability to reason.

More than any other animal, human beings desire and act as a result of habituation and reflection. In contrast to other animals, human beings can live in a thoughtful way that involves a deliberate choice of goals and a deeper awareness of goodness. The actualization of these uniquely human qualities requires massive socialization. For example, our reason allows us to discover through deliberation the kinds of goals in terms of which we can organize and interpret our actions and our lives. So we need other human beings even in order to strive to develop some conception of what human beings should strive to be and do. Moreover, we need to reflect and deliberately pursue human qualities such as fidelity, courage, or fairness in a variety of contexts and situations. These are not straightforward or easy to acquire, and part of reason’s job is to pick through the thicket of particulars that confront us in all our particularity in order to discern the right thing to do in particular situations. And since our knowledge of ourselves and our motivations are hard to discern, we need each other to help us evaluate who we are and what we are doing.

So even for the sinless citizens living in Evopolis, the best way to structure a society would not be immediately available or straightforward. And since they are in Paradise, this is not a defect. Citizens of Eden would need to talk together to think through all the different possible ways they could cooperate. They could imagine a variety of legitimate ways of meeting their needs: there are many possible ways of marrying and raising children, of engaging in economic life, of wearing clothes (if clothes exist), of making friends, or of getting an education. The central point here is that it is not a defect that we do not initially know what is good for us to be and do. And it is not a defect that we have to rely on each other to figure out what the good means in particular times and places. Rather, all this makes up our uniquely human path to perfection. God’s image and likeness shows up in human life in part when we seek our good together.

So the need for justice, the central political virtue, would persist in Evopolis. Justice is the interpersonal virtue that aims at enacting our interdependence. Politics is not merely instrumental; it is not just a tool for the expansion of individual choice. Nor is it simply about keeping people safe and secure. Nor should it be about the rule of the powerful. Politics always seeks a more or less comprehensive notion of human flourishing. This is why Aristotle called it “architectonic.” In a building project the various subcontractors and craftsmen take their cue from the architect, who decides the shape and function of the constituent building.

The architect coordinates the work of the subcontractors responsible for lighting or plumbing in light of the end for which the building will be employed. In a similar way, citizens in a healthy political order function like the architect. They manage the overall shape and direction of the constituent parts of their community inasmuch as they are always acting on some conception of what is good for human beings to be and do when they pass laws or engage in typically respectable practices.

Our interdependence requires division of labor, trust, partnerships, and cooperation across an astonishing array of activities—economic, political, familial, social. Harmonious cooperation requires the practically wise coordination of the various activities of a society. Zoning boards help determine the shape of a community. School boards decide how to educate our young. Tax laws influence our practices of family, justice, and generosity. Criminal laws reflect the way we conceive of our sexuality, our mortality, our need for moderation and responsibility. Statesmen can create rituals of memory that point to shining examples of virtue for us to follow. Politics shapes our economic lives by governing what we can and cannot sell, for example. It affects our religious practices in a variety of ways. In sum, justice is the intrapersonal virtue that coordinates the various activities of a society in a way that reaches out for a flourishing common life.

When Adam and Eve eat the fruit, everything changes. One of the most fundamental changes is that they begin to reinterpret their dependence on God, the world, and each other as a threat rather than an opportunity to become more fully human. They stop communicating with God and each other. They hide in shame. They fashion clothes to guard themselves against their vulnerability. They do not help each other evaluate goodness; they point fingers and blame.

To interpret our neediness and vulnerability as threats is to be on the way to thinking about politics as something to be mastered or avoided. To interpret our created, rational, needy interdependent nature as gifts in a divine plan is to be on the way toward a compassionate politics devoted to the common good. In light of such an anthropology, politics could not be merely about servicing the powerful, the well-organized and well-funded. Nor can it be merely about facilitating private choice for the sake of individualistic wealth, security, and comfort. Rather, it is about fostering a flourishing common life in which everyone can share in public goods.

Mutual giving and support, solidarity, generosity, especially for the weak and powerless, and evenhanded fairness are manifestations of justice. These things depend on a proper love of created goods—a right ordering of our affections and our understanding. Politics in Evopolis would exist to coordinate the practices of a community in a way that fosters genuine flourishing of everyone rather than the aggrandizement of the ruling part. It would become manifest in a practically wise sense of the overall shape and proper end of the polity, the needs and potentials of its constituent parts, and the ability to weave those parts into a harmonious, integrated community based on firm convictions about the dignity of creatures created in God’s image and likeness.

Political life would no doubt be very different in Evopolis. The politics of Eden would not be burdened by the consequences of the fall. So our citizens would not have the struggles in achieving justice that stem from our disordered affections—the tendency we have to become overly attached to wealth, offices, honors, status in ways that make just sharing so vexed. These intrapersonal misorientations have interpersonal effects that limit and distort political life. So the reality is that our politics at its best is characterized by a coincidence of interest and balance of powers among competing actors.

The main point is that in Eden citizens would have a very different orientation to our created circumstances—towards our neediness, vulnerabilities, reason and interdependence. People would view them not as unfortunate things to be transcended, but the constitutive features of their good; as the very conditions that make common life, mutuality, interdependence, and communication possible. Politics would not be a game of power, but a common activity that enacted critical aspects of the human good in ways that blossomed in civic friendship.

Conclusion

What difference does our thought experiment make? Probably not much. In political philosophy it is a version of what’s called, “full compliance theory.” This is a way of testing a theory by stipulating full compliance with its basic features. As an “ideal theory,” our thought experiment lacks practicality and bite. Still, it might help us see our strange additction in a different light. It might help us reorient ourselves to our current political circumstances and so imagine a wider horizon for thought and action.

I noted that our politics is everywhere and nowhere—that neoliberalism acts as if politics could be eliminated. Yet, politics is reasserting itself. Chantal Delsol likens us to a modern Icarus who tried to fly above the human condition, but survived his fall back to earth. Now he has to pick up the broken pieces of his life and learn how to be human again. Politics is a constituent feature of our needy, interdependent, rational condition. Trying to fly above these features of human life means we are trying to transcend our created nature rather than engage it humanly.

Such attempts always fail because the human condition always reasserts itself. And when it does we find that our failed flight has robbed us of the habits, trust, and meaning-creating symbolic structures that give form and life to the way a healthy people enacts its interdependence. As Alasdair MacIntyre has pointed out, in such circumstances we will have to reimagine and reenact what we tried to transcend; we must find a way to rebuild families, work and economic life without the traditions, resources, and habits that previously carried us through.

The reassertion of the human condition is happening all over the west in almost every important area of human life: families, the economy, religion, culture, and politics. We tried to master or deny our need for these things and now we are realizing that we have to take up them again in new ways. Our twin fantasies of escape and mastery are actually flights from the features of human life that constitute the goods of politics. On the one hand, neoliberalism is fueled by refusal: the temptation to escape from the burdens of public life into an individualism and technocratic managerialism that push away our needs and dependencies. On the other hand, it is fueled by clinging possessiveness: the desire to master our vulnerabilities through technology, wealth, or the acquisition of economic and cultural power.

It has become common in conservative circles to argue that politicking is hopeless and that we must work at the level of culture. The problem is that family, religion, civic society all live in a dependent relation to political life. So we need to revitalize the culture of politics as well. We have to reorient ourselves to political life, and that means reimaging and re-engaging the hopeful features of the human condition—reason, common speech, neediness, mutuality, interdependence, finitude, vulnerability—that modernity has been so desperate to evade and control. It means seeing them as opportunities for mutuality and conviviality—for genuine politics. Imagining prelapsarian politics is one way of initiating that reorientation.

The most pathological aspects of our lives right now are our “dependence areas”: our erotic lives, our families, our work, our economy, and our politics. In different ways, these have been commodified and instrumentalized. They are no longer the ways through which we transcend our narrow, self-enclosed desires—the ways we learn to love our beloveds, our earth, our countries, our families, and our fellow citizens. Instead, they have become the loci for individual satisfaction and choices. We have rendered them mute and inert; desiccated and sterile. The result is a fissiparous anomie that is increasingly spilling over into violence. This is our strange, intolerable addiction. We are tempted to think that all that is left to us is a series of bad choices. We might withdraw from politics in a fit of disgust. Or, we might acquiesce to the Machiavellianism of forcing our “values” onto the public through a radically defective strongman.

In the end, these are the ways our addictive behaviors get us in their grip. They manifest our refusal of one of God’s great gifts: the gift of political life. They tempt us to despair instead of hope. We must resist our temptations to refusal and clinging possessiveness with every breath. We only do that by learning how to love instead.