Europe’s supreme gift was the gift of African identity, bequeathed without grace or design—but a reality all the same.

—Ali Mazrui

When the genocide broke out in Rwanda in the spring of 1994, I had been living in Belgium for almost three years. Having finished my master’s in philosophical ethics, I was just starting my PhD research on moral rationality at the KU Leuven Hoger Instituut voor Wijsbegeerteat (Higher Institute of Philosophy). I was living at the Heilig Geest College, formerly a seminary for Flemish seminarians, which had been turned into a residence hall and housed a number of foreign priests, mostly from Africa, India, and the Philippines. The fact that Rwanda was a former Belgian colony and that ten Belgian UN soldiers had been killed at the start of the genocide meant that the event received extensive coverage in the Belgian press. At the Heilig Geest College we had one television set in the common room, where a number of us foreign priests and a few Belgian students gathered to watch the news. As the genocide unfolded, we watched in silent disbelief as bodies of Rwandan children, women, and men floated in rivers, piled up in churches, and decomposed by the roadside.

It was not just the speed and efficiency of the killing (in less than a hundred days, close to a million people were killed, mostly using machetes, sticks, and rudimentary weapons) that baffled us into silence, but also its intimacy. Neighbors killed neighbors, family members killed family members, priests and the religious killed members of their congregations and the other way round. There was very little to say; we could only watch in stunned silence as the brutality and inhumanity of the genocide raised questions about the sacredness of human life and even what it meant to be human. The genocide also raised doubts about global human community and solidarity, as we saw scenes of hundreds of Rwandans seeking protection at various Western embassies and compounds, only to be abandoned to the Interahamwe militias as foreign governments evacuated their nationals. Barely fifty years after 147 states had vowed “never again” and signed the Genocide Convention, the world turned a blind eye on Rwanda. The reason, it would become increasingly clear, was that Rwanda was an African country of little strategic interest to Western governments. Are there any bonds of community and society that transcend national interests, I wondered?

But the genocide also raised a number of questions about Africa: about ethnicity and community in Africa, about recurrent patterns of violence across the continent, about the so-called African traditional values of communality and solidarity, and ultimately, about what it means to be an African. Kurian, an Indian priest friend enrolled in the same PhD program as I was, turned to me one evening as we were heading out of the common room after watching the news from Rwanda and asked, “Why do your people always kill each other like this?” I was not sure whether “your people” in Kurian’s question referred to Rwandans, Hutus, or Africans. Kurian might have sensed my hesitation, and so he clarified, “I mean, why do you Africans always kill your own people?”

I was deeply troubled by the question. As if the images of the genocide were not enough, here was another example of Afro-pessimism, I thought to myself, this time coming not from the usual suspects, Western racists and bigots, but from an Indian! What did he know about Africa? Where in Africa had he been? On what basis could he generalize from a case of genocide happening in one country to “Africans”? He probably thinks Africa is one village, or one country. I wanted to fight back, but all I could muster at that time was a more measured response. “Not all of Africa is having genocide,” I told Kurian. But the question continued to haunt me in ways that, looking back, I see have driven my scholarship. For I now realize that most of my work has been an attempt to understand the nature and recurrent patterns of violence in modern Africa. This attempt culminated in The Sacrifice of Africa, in which I traced the violence in Africa to what I called the imaginative landscape of Western modernity on the continent. I argued that the prevailing forms of violence in Africa are not merely hangovers from Africa’s primitive or premodern past (reflecting ancient hatreds between tribes) but a modern phenomenon that has partly to do with the stories that shape modern Africa, and thus the stories with which modern Africans live. These stories are embedded within and help to sustain the modern institutions of politics, education, and economics in Africa. As Patrick Chabal and Jean-Pascal Daloz argue, violence, disorder, and corruption are not the exception. They are the way modern Africa works. What I sought to make clear in The Sacrifice of Africa, drawing on the work of scholars like Benedict Anderson and William Cavanaugh, is that this “imagining” of Africa has greatly to do with the stories that justified and informed Europe’s modern (that is colonial) project on the African continent. I argue that even though colonialism has officially ended in Africa, the nation-state (the successor political institution as well as its related economic and social institutions in modern Africa) still operates out of the same imaginary that there is “nothing good out of Africa.” Wired within the architectural foundations of modern Africa, this story supports the ongoing devaluation and sacrificing of African lives by fellow Africans. For this reason I claim in The Sacrifice of Africa that what is required, even more than the usual attempts to stem violence in Africa, is a fresh social imagination of Africa and of Africans. We need another imaginary, and for this, another and better story.

However, beyond the immediate questions of the 1994 violence, Kurian’s question helped to bring into sharper focus some of the questions I was already having about African identity. What does it mean to be African? What is it that I share with other Africans that makes them “my people” more than any history, friendship, or relationship with Europeans or Americans could ever make them “my people”? Is it the color of my skin, history, geography, or culture that makes me naturally, and thus without effort, allied to other “Africans” more than to a Belgian or Norwegian? What does it mean to belong to a group of people called Africans? On one level, these were philosophical questions, the kind of questions that only a scholar would raise. On another level, however, they were existential questions, for being “African” was not only a speculative question for me but a fact of everyday life. When people saw me on the streets or in the classroom at Leuven, they saw me, treated me, and related to me as an African.

Related to my being “African” were further questions of identity connected to the association of “Africa” with “tribes.” Whenever I would introduce myself as from Uganda, people would sooner or later ask, “What is your tribe?” For more than personal reasons, I always had problems with the word tribe. Some of these objections were confirmed by the Rwanda Genocide. The standard way the genocide was explained was in terms of “age-old animosities” between Hutu and Tutsi tribes, which had now exploded into “ethnic” violence. But whatever notion of a tribe one has, Hutus and Tutsis did not seem to fit within the usual notion of “tribe.” They spoke the same language; shared the same culture, history, and religion; and were closely intermarried. In fact, as the missionary Louis de Lacger said of Rwandans in the 1950s, “There are few people in Europe among whom one finds these three factors of national cohesion: one language, one faith, one law.” What then is a tribe and what is tribal identity, I found myself asking afresh. Again, the question was not simply speculative. I had a personal interest in it. My parents had migrated from Rwanda in the late 1940s and settled in Uganda, where I was born. Whenever I told this story, some of my friends would say, “But that means you are really Rwandan.” All they wanted to know was whether I was Hutu or Tutsi. But since one of my parents was Hutu and the other Tutsi, I was always left wondering, “What is my tribe? Am I Hutu or Tutsi?” I did not speak Kinyarwanda and had been to Rwanda only once, when I was a child. What was it then that made me really Rwandan, and Ugandan only superficially, I wondered. Who am I, and who are my people, anyway?

As I struggled with this identity crisis and sought answers, I took interest in the work of other African scholars who had also pondered the question of “Africa” and “African identity.” Three scholars whose work I found particularly helpful in sorting through the jumble of ideas of what it means to be African are Valentin Mudimbe, Ali Mazrui, and Anthony Appiah. By briefly sketching what I found illuminating about the work of each of these scholars in my attempt to grapple with the question of “African” identity, I will provide an outline of the processes and assumptions that have led to a particular vision of “Africa” and “Africans” in modern history. My interest here is to offer the reader, not a comprehensive discussion and assessment of these authors’ works, which obviously lies outside the scope of this book, but a sense of the scholarly journey that led me to the realization that identities are not things or entities grounded in an enduring essence. Identities have to do more with imagination. Accordingly, “African” identity (not unlike “tribal” or “ethnic” identity) is not a reflection of some metaphysical essence or some biological, geographical, or cultural oneness. Rather, it is the way that Africa and Africans have been imagined (by others and by themselves), and of the shared history shaped by this imagining. Moreover, since “African” identity is not a static thing or essence, there are many ways of being an African, largely related to who one is and where, when, and how one finds oneself located in the story of Africa. In the end, then, what we need is not so much a definition of “African” identity as stories that depict helpful and not-so-helpful, violent and nonviolent ways of negotiating the limits and possibilities of any identity, in this case “African” identity.

Mudimbe on the Idea of “Africa”

It was the Congolese-born philosopher, novelist, and literary critic Valentin Mudimbe who first helped me see that “Africa” was not so much a place as a concept, not so much a geographic designation as an idea. I discovered Mudimbe around the time of the Rwanda Genocide, having first encountered his work in a PhD seminar on phenomenology. He is widely considered the Edward Said of African studies, and his The Invention of Africa is as significant to the field of African studies as Said’s Orientalism has been to postcolonial studies. Even though, with his background in classic literature and French poststructuralism, Mudimbe’s writing is not always easy to follow, I found his central argument and insights illuminating.

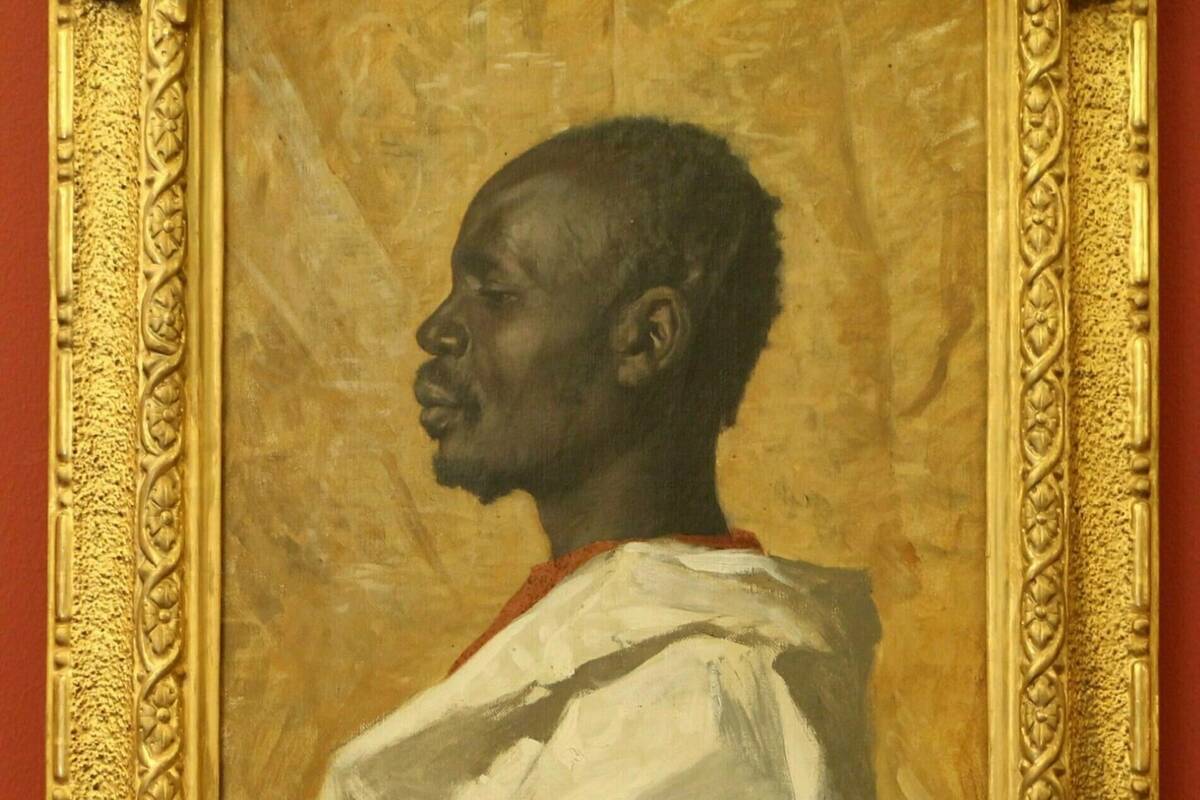

Mudimbe’s central concerns are conceptual and methodological, or, more fundamentally, epistemological. He is interested in the way “Africa” is represented in a variety of texts and discourses, and he seeks to explore the epistemological context that makes possible a particular discourse on Africa at a given time and place. Until relatively recently, Mudimbe notes, these discourses originated outside Africa, primarily in Europe. These representations have been integral to the history of Europe’s expansion and quest for imperial power: that is, they are associated with the slave trade and institutions of slavery in the Americas, with colonial conquest, and with Christian missionary activity. Thus for Mudimbe the representations of African cultures and societies found in the writings of various early explorers, missionaries, merchants, travelers, and European armchair commentators are dominated by the need to present Africa in a particular way so as to bolster the European colonial adventure in Africa, which Mudimbe describes as a tripartite project of conversion. The three parties to this project were first the missionaries, who claimed that Christianity would bring “true light” to local tradition. Second was the colonial administration, whose aim was to convert “savage spaces” into “civilized” ones. The third partner was the newly founded discipline of anthropology, designed to codify local human behavior and institutions in the colonies.

It is in this sense that Mudimbe speaks of the “invention” of Africa— imagining Africa as the other of Europe. This imagination plays a double role in the European project. First, the “discovery” of a dark, pagan, and barbaric Africa confirms Europe’s own identity as enlightened, Christian, and civilized. Hegel’s view of an Africa without a history is most often mentioned in the literature, but the phenomenon was much more general.

Second, to confirm the European sense of mission, “The West,” Mudimbe notes, “created the ‘pagan’ in order to ‘Christianize,’ ‘underdevelopment’ in order to ‘develop,’ the ‘primitive’ in order to engage in ‘anthropology’ and ‘civilize.’” This is also what makes “Africa” more of an “idea” than a place. One gets this sense of the “idea” of Africa when asking a European if they have been to Africa and receiving a reply like “I have been to Egypt, but have never been to real Africa.” The first time I visited South Africa, I was surprised when I encountered many South Africans talking about going to, or never having been to, Africa (that is, north of the Limpopo River). Some of these were the same people who on other occasions would insist they were “Africans”! In both instances the implication was that real Africa, “Africa proper,” as Hegel had put it, was a “dark” and primitive continent “lying beyond the day of selfconscious history.”

This is neither the time nor the occasion to critically engage Mudimbe’s work, but one clear takeaway from it is that “Africa” emerges in the post-Enlightenment European imagination and discourse as disabled, deficient, and lacking—lacking religion, history, civilization, development, democracy, human rights, and ethics. Achille Mbembe was later to make the same observation when he noted that the African human experience constantly appears in the discourse of our time as understandable only through a negative interpretation: “Africa is never seen as possessing things and attributes properly part of ‘human nature.’ Or, when it is, its things and attributes are generally of lesser value, little importance, and poor quality. It is this elementariness and primitiveness that makes Africa the world par excellence of all that is incomplete, mutilated, and unfinished, its history reduced to a series of setbacks of nature in its quest for humankind.”

Edward Said would make a similar point about the Orient in Orientalism. But while Said would insist that the Orient does not exist and has never existed outside the imagination of the West, Mudimbe, even without saying so explicitly, seems to suggest that the invention of Africa is a self-fulfilling prophecy. The imagination of a dark, primitive, and underdeveloped Africa succeeds in inventing the very continent that is imagined.

Stanley Hauerwas, the American theologian and ethicist, whose work I was investigating for my PhD dissertation, had already helped me to see how stories shape not only personal identity but also the world in which we live. To understand the characters or identities formed within a given politics, Hauerwas had argued, it is important to understand the stories that shape that politics, especially what is assumed “in the beginning.” Later, I was to confirm this conclusion in relation to Rwanda by examining the Hamitic mythology that had been used to colonize and evangelize Rwanda (defining Hutu as “natives” and Tutsi as “foreigners”).

As the Hamitic story of separate origins was used to describe people who spoke the same language, lived on the same hills, and had the same culture, it succeeded in forming a political community (modern Rwanda) where Tutsi and Hutu actually became separate communities, united in their hatred of each other. But that was to come later. At this stage of my intellectual development, during my graduate studies, the full implications of Mudimbe’s work would only gradually become clear. The work of Ali Mazrui was helpful in this development, as it confirmed that while modern Europeans were not the first ones to know and relate to Africa, there was something unique about the modern encounter between Europe and Africa, an encounter that would not only result in the “invention” of modern Africa but shape the processes, contradictions, and institutions that constitute what we can call Africa’s unique modernity.

Mazrui on the Ongoing Invention of Africa

Once described by Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary-general, as “Africa’s gift to the world,” Ali Mazrui was named in 2005 by Foreign Policy and The Prospect as one of the world’s top one hundred public intellectuals. I had been a great admirer of Ali Mazrui ever since I first watched his popular BBC series The Africans: A Triple Heritage in 1990. In the series, Mazrui comments on the history, geography, and culture of Africa, discusses native, Arab, and Western influences on the continent, and provides penetrating insights and anecdotes on African politics, sports, and religion as well as other aspects of life on the continent. I had since read and used some of his work in my courses and was very much looking forward to meeting him in person, but that was not to happen. In the process of my putting together a research team on the issues of authority, community, and identity in Africa in the Contending Modernities Project, he and I corresponded, and I invited him to speak at Notre Dame. At that time, he was at the State University of New York. He agreed and came to speak at Notre Dame in 2013. However, the day before he came to campus, a medical emergency took me to hospital, so I missed both his visit and talk. He passed the following year.

In 2005, Mazrui wrote a very influential essay, “The Reinvention of Africa,” which provides helpful insight on the ongoing imagination of Africa. In the essay, commenting on the work of Mudimbe, Mazrui notes that “Africa” (how Africa has been defined) is the product of its interaction with other civilizations, not simply Europe. These interactions are partly reflected in the name “Africa.”

Some have traced the name to Berber origins; others have traced it to a Graeco-Roman ancestry. The ancient Romans referred to their colonial province in present-day Tunisia and eastern Algeria as “Africa,” possibly because the name came from a Latin or Greek word for that region or its people, or perhaps because it came from one of the local languages of that region—either Berber or Phoenician. Here are the origins of the invention of Africa. Did the Romans call the continent after the Latin word Aprica (meaning “sunny”)? Or were the Romans and the Greeks using the Greek word Aphrike (meaning “without cold”)? Or did the name come from the Semites (Phoenicians) referring to the productivity of what is today Tunisia—a term that means “Ears of Corn”? Later the Arab immigrants Arabized the name into Ifriqiya.

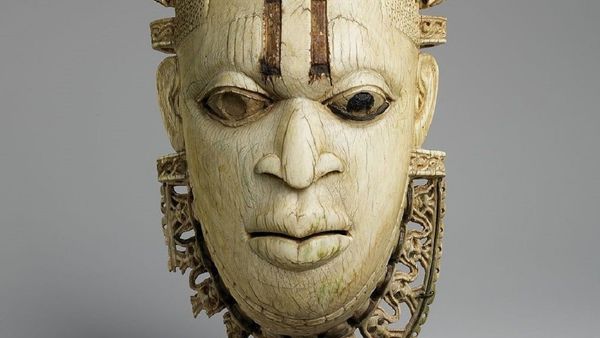

According to Mazrui’s 2005 essay, the history of the external conceptualization of Africa has had five phases. The first phase regarded North Africa as an extension of Europe and the rest of Africa as an empire of barbarism and darkness. The second phase was defined by the interaction with the Semitic people and with classical Greece and Rome. This was the era when Christianity as a Semitic religion spread across North Africa and into Ethiopia. The third phase involved the birth of Islam on the Arab peninsula and its expansion into Africa. At this stage, which lasted for several centuries, much of West Africa was the product of two civilizations—indigenous African culture and Islam. This duality included the great empires of Mali (ca. 1230 to 1670) and Songhai (ca. 1325 to 1591), with Timbuktu as the most historically significant city produced by the two empires. The fourth historical phase involved the Western impact in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which coincided with European colonialism—a crucially significant phase whose effect was the making of modern Africa as a product of a dialogue between three civilizations: African, Islamic, and Western. The convergence is what constitutes Africa’s “triple heritage,” which was the subject of Mazrui’s 1986 BBC television series, The Africans: A Triple Heritage. The fifth phase of the historical conceptualization of Africa was the realization that the continent was the birthplace of the human species. Africa thus became the Garden of Eden and a major stream in world civilization. A transition occurred from Africa’s triple heritage to the paradigm of Afrocentricity—and from the Dark Continent to the Garden of Eden. “This final paradigm,” in Mazrui’s opinion, “globalizes Africa itself.”

In identifying these phases, Mazrui not only confirms Mudimbe’s insight of the “idea” of Africa but shows that “Africa” is not a static notion or concept but an ongoing reality that is invented and continues to be reinvented in the context of Africa’s relation to other civilizations. Therefore, “Africa” or being “African” does not mean the same thing at every phase of Africa’s conceptualization. In this connection, Mazrui notes that one of the paradoxes of history is that it took Africa’s contact with the Arab world to make Africans realize that they were black, even though for Arabs this was merely a description, not a judgment about their status. The fact that Islamization in Africa awakened black consciousness without promoting black inferiority can best be illustrated by the reputation of classical Timbuktu, which was recognized as black and still saluted as a civilized achievement. This would, however, change with the European contact of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This “modern” European contact Africanized Africa in at least three unique ways.

First, European cartography and mapmaking turned Africa into the continent as we know it today. Europeans may not have invented the name “Africa,” but they played a decisive role in applying it to the continental landmarks that we recognize today.

Second, according to Mazrui, European racism convinced at least sub-Saharan Africa that one of the most relevant criteria of their Africanity was their skin color. Moreover, to Europeans black was not merely descriptive; it was also a judgment. Thus, while contact with Arabs alerted the people of sub-Saharan Africa that they were black, Europe associated their “blackness” with inferiority.

Third, closely related to racism, Mazrui notes, was the experience of European imperialism and colonization on the continent. The humiliation and degradation of black Africans across the centuries contributed to their mutual recognition of each other as “fellow Africans.”

Thus the process of the Africanization of Africa through contact with modern Europe was to give rise to a sense of shared “African identity.” Mazrui notes: “It is one of the great ironies of modern African history that it took European colonialism to inform Africans that they were Africans. . . . Europe’s greatest service to the people of Africa was not Western civilization . . . or even Christianity. Europe’s supreme gift was the gift of African identity, bequeathed without grace or design—but a reality all the same.” There was another gift, namely the gift of a continent that is mired in various contradictions, which Mazrui depicts as the “paradoxes” of Africa’s postcolonial condition in his 1979 BBC Reith Lectures, later published as The African Condition: A Political Diagnosis. He identifies six paradoxes or contradictions. The first is the “paradox of habitation,” which describes Africa as a continent that has been identified as the “cradle of mankind” but one that remains the least inhabitable. There is also the “paradox of humiliation,” which highlights how Africa is a product of a humiliating history of enslavement, colonization, and racial discrimination. The third paradox is the “paradox of acculturation,” cascading from the imposition of foreign cultural, political, economic, and social forms that disturbed and reproduced Africanity as a conflicting set of identities. The fourth is the “paradox of fragmentation,” rooted in capitalist economic exploitation that reproduced Africa as a site of underdevelopment, maldistribution, and economic disarticulation. The fifth is the “paradox of retardation,” manifesting itself in the form of Africa’s failure to act as a unit as a result of internal fissuring from national, ethnic, ideological, and religious cleavages. The last is the “paradox of location,” which speaks to how a continent that is centrally located is at the same time the most marginal in global power politics.

For Mazrui these paradoxes are related to—or rather are—the way modernity is experienced in Africa. They constitute Africa’s unique modernity, a unique social history and African identity shaped by contact with European modernity. The Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka has similarly commented on this unique African modernity. Soyinka notes that the African continent does not exist in isolation but is an intimate part of the history of others. In this connection, Africa has always been “known about, speculated over, explored both in actuality and fantasy, even mapped—Greeks, Jews, Arabs, Phoenicians etc. took their turns.” And even though he does not say so as explicitly as Mudimbe or Mazrui, for Soyinka what is different about the eighteenth and nineteenth-century European contact with Africa is the unique way in which Europe “fictionalized” the continent as the object of European colonial adventure and commercial interest, thus turning Africa into a “monumental fiction of European creativity”—an imagination that has largely remained in place until today. This, for Soyinka, constitutes what he calls the “crisis of African emergence into modernity.” It is most evident in Africa’s postcolonial leadership as “largely a crisis of leadership alienation.” By this Soyinka means that even as Africa’s postcolonial political leaders seek to inaugurate a new era in Africa’s independence, or “liberation,” they do so “with the same mentality of domination and/or exploitation” as the West, thereby perpetuating the same agenda as their colonial predecessors. It is this phenomenon that I describe in The Sacrifice of Africa as the looming shadow of King Leopold’s Ghost that continues to define and shape Africa’s imaginative landscape. However, by pointing to leadership alienation as one manifestation of the crisis of Africa’s unique modernity, Soyinka draws attention to the contradictions at the heart of postcolonial African society—the postcolony, as Mbembe would call it. In the postcolony, the ruling power is no longer an alien (European) colonial master race subjugating “primitive” and backward peoples but a “son of the soil” who nevertheless continues to carry the “white man’s burden”—and thus often views himself as a divinely appointed shepherd among a mindless flock. In his desperate attempt to hold onto power, he “fictionalizes” the population as not “ready for democracy” or the country as still lacking a capable replacement for him.

Here Mazrui and Soyinka converge regarding the African postcolonial condition as one characterized by “paradoxes” or contradictions that arise out of Africa’s contact with European modernity. And even though Mazrui does not offer much in terms of suggestions for a way forward out of these paradoxes within Africa’s postcolonial condition (neither does Soyinka) his work proved particularly helpful in my attempt to understand Africa’s unique modernity and the paradox of violence that arises from within it. In this connection, the Rwanda Genocide is particularly telling and does indeed serve as a “metaphor” (as Mamdani rightly notes) for the paradox of violence. For the kind of violence that we witnessed during the Rwanda Genocide—neighbors killing neighbors, family members killing other family members—does not make sense, especially in a country and a people (Rwandans, Africans) so often known for their sense of communal and family solidarity, for hospitality and generosity even to strangers. How could this be possible? What is going on? In light of Mazrui’s work, I began to see how the Rwanda Genocide and other outbursts of “ethnic” violence in Africa become thinkable within the context of a larger set of contradictions and paradoxes that constitute Africa’s modern condition. Such violent outbursts do not make sense outside the crisis occasioned by the European “discovery” and thus “invention” of Africa as a modern “dark continent.”

If Mudimbe’s The Invention of Africa helped me to begin to understand Africa as an “imagined” reality, Mazrui confirmed that Europe’s interaction with Africa was to invent Africa in a unique way—to bequeath not only the “gift” of a shared sense of “African identity” but a continent that is in many ways still reeling from the “crisis of African emergence into modernity.” It is this modernity into which Africa is received (and that Africa receives) as at once a gift and burden, a promise and an impossibility (for the continent is perpetually modernizing, yet stuck in “darkness” and in its “primitive” destiny). Thus, from the start, the European modernity into which Africa is received will define Africa as at once a victim (humiliated by enslavement and colonialism), a victor (triumphant in its historical achievements), and a villain (home of unbridled corruption, greed, and violence). How do we proceed in the face of these paradoxes and contradictions of modern Africa? As noted, Mazrui does not provide much guidance. But of course, there can be no return to a premodern glorious past of Africa’s independence. No such thing ever existed, even if a return were available. For as Mazrui rightly notes, Africa has always historically been defined through its interaction with other civilizations. But by the same token, since there is no such thing as an ahistorical “Africa” or an enduring “African identity,” an appeal to recover African identity as the foundation of a new modernity in Africa cannot provide much hope in the midst of the paradoxes and contradictions that beset the continent. In fact, appealing to an African identity might turn out to be misleading and disabling, as Anthony Appiah makes clear.

Appiah on the Pitfalls and Usefulness of African Identity

Around the time I read Mudimbe’s The Invention of Africa in the spring of 1994, I also chanced upon Anthony Appiah’s 1992 collection of essays, In My Father’s House, in which Appiah critically examines the discussion of African intellectuals on what it means to be African. Among other things, Appiah arrives at the conclusion that African identity is not a stable metaphysical essence or “oneness” but rather a way of locating oneself or being located in the world. It is not the only way, but it reflects a shared history of subjugation of peoples from the African continent. Given this conclusion, Appiah takes issue with how the notion of African identity has been historically used as a rallying call in ways that assume either a racial unity, a biological essence, or a cultural oneness. First, Appiah notes, the “myth” of racial unity as the basis of African identity, which in many ways has defined the debates on African identity, must be rejected. For generations who theorized the decolonization of Africa (Nkurumah and others), “race” was a central organizing principle. This principle (of the essential unity of the Negro race) was inherited from the African American fathers of pan-Africanism (Crumwell, Du Bois, Blyden), who took for granted the distinction between black and white races. However, Appiah notes, the notion of race as a defining factor of African identity is both misleading and disabling. In the first place, by accepting the black/white distinction initially employed by the colonizers, the pan-Africanists subordinated themselves to (and thus perpetuated) the discourse providing the ideology for their domination. Even though they sought to redefine “Negro identity” from a negative to a positive designation, a move that was necessary in the dialectics of the struggle against white domination, this effort simply perpetuated it. That is why, for Appiah, if we are to define African identity today we must discard the biological notion of race as well as the dichotomy of “we/blacks” and “they/whites.” Not only does the dichotomy entail a scientifically untenable notion of race, it is based on an erroneous essentialism that assumes some deep similarity at the core of every identity that binds the people of that identity together. Such a view creates an illusion that black (and white and yellow) people are fundamentally allied by nature and, thus, without effort. In this way, it leaves us totally unprepared to understand, let alone “handle[,] the ‘intraracial’ conflicts that arise from the very different situations of black (and white and yellow) people in different parts of the economy and of the world.” Overall, I found Appiah’s argument convincing and his In My Father’s House quite helpful in my attempt to philosophically understand the issue of identity in general and African identity in particular, and more specifically in my attempt to come to terms with my “Africanness” in the wake of the Rwanda Genocide. Appiah advanced my thinking in four crucial ways.

First, reading In My Father’s House in the wake of the Rwanda Genocide, I could immediately relate Appiah’s critique of racial unity as the foundation of African identity to the issue of “tribe” and “ethnicity” in Africa. I could see that through a similar process “tribal” identity became an unquestionable building block for the African nation-state. For the colonialists, Africans lived in “tribes.” But tribe also named whatever was primitive, backward, unmodern, in a word, all that modernity came to “civilize.” When the architects of African independence accepted the notion of “tribe,” which had initially been employed by the colonizers, and redefined it in positive terms (the redefinition would later see the rejection of language of “tribal identity” in favor of “ethnic identity”), they took a necessary step in the dialectics of the struggle against European colonialism, but at the same time they also unwittingly subordinated themselves to the same politics of “difference” that was the basis of Africa’s subjugation.

What Appiah was helping me see was that the idea of “tribal” or “ethnic” unity, like the idea of “racial” unity, is a myth that does not reflect the reality of the multiple identities that Africans bear. For as Appiah notes, given the “circulation of cultures,” there can be no such thing as a pure Igbo, Western, or African culture, no such thing as “a fully autochthonous echt-African culture” or identity. “We are already contaminated by each other.” We find ourselves always caught up in many entanglements and identities, so that it is a “lie” to reduce these to one identity that is really me! Appiah’s own polyglot identity is a telling case: he was born in London of an Asante father and an English mother, was raised in Ghana and educated in Britain, and is now teaching (living) in the United States. But Appiah was also helping me see that because the categories of difference often cut across our economic (and political) interests, the myth of racial or tribal unity often serves an ideological goal: to blind us to these economic and political interests. In this way, the appeal to “racial” or “tribal” unity prevents oppositional attitudes from generating a “coherent alternative view, which would provide a basis for political action.” As Appiah notes, “The inscription of difference in Africa today plays into the hands of the very exploiters whose shackles we are trying to escape. ‘Race’ in Europe and ‘tribe’ in Africa are central to the way in which the objective interests of the worst-off are distorted.”

Another crucial insight that emerged from Appiah’s In My Father’s House was that even though Appiah rejected the myth of a biological, metaphysical, or mythic unity or even a singular worldview as the basis of identity, he did not dismiss the notion of identity. As he would later note in Lies That Bind, “There is no dispensing with identities but we need to understand them better if we are to reconfigure them.” Identities are historical-political actualities and are thus fluid and always in an ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation. Accordingly, he notes in In My Father’s House, the idea of African identity is a fact. Being African already has “a certain context and a certain meaning. . . . We share a continent and its ecological problems, we share a relation of dependency to the world economy, we share the problem of racism in the way the industrialized world thinks of us.” However, this identity is based, not on a shared essence, a “common stock of cultural knowledge,” or a “central body of ideas” shared by Africans, but on common history, problems, and interests. Moreover, being African is not a static identity; like all identities, it is fluid and dynamic and is thus capable of being constantly shaped and reformed in the context of present realities and future ideals and aspirations. It is in this respect that the idea of “African identity” can prove useful. For given the shared history of colonialism and the common problems resulting from the history of colonial subjugation and marginalization, the idea of “African” identity can be a useful organizing concept to mobilize continental and global alliances in the emancipatory struggles of African peoples. “A Pan-African identity, which allows African-Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Afro-Latins to ally with continental Africans, drawing on the cultural resources of the Black Atlantic World, may serve useful purposes.”

What is evident in the foregoing remarks is Appiah’s rejection of an essentialist view of African identity in favor of a pragmatic conception of identity. Later in Lies That Bind he will note: “Identities . . . divide us and set us against one another,” but they can also unite us. The idea of “Africa” can be used to foster solidarity in the pursuit of justice and liberation for the excluded and marginalized. At the same time, Appiah warns, African identity, like other identities, is not exclusive—it is for its bearers one among many. Accordingly, while African solidarity can surely be a vital and enabling rallying cry, “In this world of genders, ethnicities, and classes, of families, religions, and nations, it is as well to remember that there are times when ‘Africa’ is not the banner we need.” I found this observation refreshing, as it could articulate much of the uneasiness I was feeling at that time about the “fixity” of my being “African” in Belgium. For to a number of people that I met at KU Leuven, including some of my professors and even fellow students, the only thing that mattered was that I was “African.” It was as if I did not have any other story, any other identities, any other interesting projects to pursue, except to be “African.” The label “African,” it seemed, had named all that they needed to know about me!

Appiah’s In My Father’s House was also invaluable to me in terms of pointing to the need for “testifying” and the primary role of stories in making the case for or against the usefulness of African identity. All identities are relative, Appiah notes, and thus “We must argue for and against them case by case.” The arguing is not so much a theoretical exercise as a practical and ethical imperative. He notes, “It is also important to testify . . . to the practical reality of the kind of intercultural project whose theoretical ramifications I explore . . . to show how easy it is, without theory, without much conscious thought, to live in human families that extend across the boundaries that are currently held to divide our race.” In In My Father’s House Appiah constantly returns to the story of his father and his multiple identities—as an Asante, a Ghanaian, an African, a Christian, and a Methodist—“to learn from his capacity to make use of these many identities without, so far as I could tell, any significant conflict.” Appiah’s reference to the story of how his father was able to negotiate his many identities and their obligations without feeling the need to resort to violence struck a deep chord in me. I had encountered a similar emphasis on narrative and story in the work of Stanley Hauerwas. In fact, as already noted, through Hauerwas’s work I had already come to appreciate the role that stories play in shaping individual and communal identities. From Hauerwas I had also learned that two key criteria for assessing the truthfulness of a story had to do with the sorts of characters it was capable of shaping and whether the story offered sufficient skills and resources for individuals to negotiate the contradictions of their lives without resorting to violence. But of course this could not be known a priori, but only through stories. For Hauerwas, therefore, a narrative methodology was essential as the only way that characters formed by a story, as well as the limits and possibilities of the story for negotiating everyday challenges, could be displayed. Stories for Hauerwas provided both the argument and the evidence that a different world is possible.

Appiah’s In My Father’s House was pointing in the same direction, thus confirming that the issue of “African identity” (what it means to be “African”) is an issue that can be settled, not through philosophical speculation, but only narratively, by displaying the various ways in which “African identity” has been invoked in a number of contexts and the various purposes for which the notions of “Africa,” “Africanness,” and “African identity” have been deployed. Not only had Appiah succeeded in doing this, thus dispelling the myth of a stable, essentialized notion of African identity, he had also confirmed that there are many ways of being an African—many ways of bearing African identity. Stories are what we need if we are to see the possibility of living in “human families that extend beyond the boundaries that are currently held to divide our race.”

Finally, Appiah’s In My Father’s House confirmed a restlessness I was already beginning to feel about theoretical speculation and the life of the academy in general. Here I was one of the very few African students to be admitted into KU Leuven’s doctoral programs in philosophy, with the hope of perhaps one day holding a chair in philosophy at a university in my home country or somewhere else. I should have been happy and proud of myself. But I was not. Instead, even before the 1994 Rwanda Genocide, I was feeling restless. What was the use of all this philosophical speculation? What did it amount to? With the Rwanda Genocide, I turned to seeking to understand the reality of Africa and how such violence as the genocide could ever make sense. Kurian’s question had set me on a journey of philosophical exploration on the status of “Africa” and the nature of “African identity.” And the works of Mudimbe and Mazrui had thrown light on the complex processes of the ongoing imagination of “Africa.” But in pointing to the need to “testify” to the possibility of inter and cross-cultural peaceful coexistence, Appiah was also pointing to the limits of theoretical speculation and highlighting the need for practical commitment and interventions that engage “the dialects of need.” This of course does not mean that for Appiah theoretical, philosophical speculation is totally irrelevant and therefore cannot contribute to the advancement of cross-cultural understanding and solidarity. He notes, “What we in the academy can contribute—even if slowly and marginally—is a disruption of the discourse of ‘racial’ and ‘tribal’ differences.” No doubt, this task is important, for “‘Race’ in Europe and ‘tribe’ in Africa are central to the way in which the objective interests of the worst-off are distorted” (179). In the end, however, the possibility of a different Africa calls for practical forms of engagement that meet Africa’s dialectics of need. “Every time I read another report in the newspapers of African disaster—a famine in Ethiopia, a war in Namibia, ethnic conflict in Burundi—I wonder how much good it does to correct the theories with which these evils are bound up; the solution is food, or mediation, or some other more material, more practical step.”

When I first read this statement in 1994 it was Appiah’s observation about the limits of the academy and theory that struck me. Looking back, however, I realize that the need to engage the material realities of Africa—“food, mediation, or some other material [needs]”—has been far more determinative in my journey than I would have imagined then. Appiah had noted, “We cannot change the world simply by evidence and reasoning, but we surely cannot change it without them either.” So I now find myself, as a scholar, trying to disrupt the discourse of “racial” and “tribal” identity, and as a practitioner, engaged in Africa’s dialects of need: food, mediation, ecology, and economy. In all this, I am trying to come to terms with the issue of my African identity: not simply what it means to be an African (in the abstract) but what it means to be this particular African, with the hope that my story as well as the stories of others I tell in this book can testify to the possibility of living in families and communities that extend across the boundaries that are currently held to divide us.

Conclusion: On a Theological Doorstep

If the violence of the 1994 Rwanda Genocide and Kurian’s question had set me on a theoretical exploration on the status of “Africa” and the nature of African identity, with Appiah’s In My Father’s House, that exploration had led me to a practical and ethical conclusion: African identity reflects shared historical, cultural experiences and emergent forms of international organizations in the modern postcolonial world. But like any identity, it is not the only way that its bearers view themselves. Moreover, there are good and bad ways, violent and nonviolent ways, useful and not-so-useful ways of living in this unique modernity. Kurian’s question “Why do you Africans always kill your own people?” requires more than theoretical arguments to account for the reality of Africa and its violent contradictions and outbursts (necessary as these are): it calls for stories that testify to the possibility and reality of a different “Africa” and for concrete practical and material engagements that reimagine, and thus invent, a different modernity in Africa.

Appiah’s reflections also landed me on a theological doorstep. To be sure, it was the hint of this theological opening that first drew me to Appiah’s In My Father’s House. For as he himself notes, the title refers first not to Appiah’s father but to God. He elaborates, “Thus for me the phrase ‘in my father’s house’ must be completed ‘there are many mansions’—and the biblical understanding that, when Christ utters those words at the Last Supper, he meant that there is room enough for all in heaven, his Father’s House.” Even though Appiah does not explore the full implications of this theological opening, I was increasingly fas cinated by it and sought to explore its concrete practical and social possibilities for the here and now. At the time I was working on a PhD in philosophy on issues of moral rationality, the Rwanda Genocide was, even without my full awareness, beginning to shift my intellectual orientation in a decisive theological direction. Part of this shift was no doubt connected to my identity as a Catholic priest, and as a priest I am always naturally drawn to the theological and ecclesial implications of whatever engagements I find myself part of. But the other reason was that I was studying the work of theologian Stanley Hauerwas and had found his argument for the need for a distinctive theological voice quite persuasive. At any rate, with the Rwanda Genocide happening in a country that was predominantly Christian, and with the widespread participation of Christians in the genocide, I found myself constantly wondering about the issue of Christian identity in Africa. What difference if any, does being a Christian make to the way that one understands one’s own identity? And how does this understanding of oneself as a Christian relate to one’s being an African, or a member of a particular tribe or ethnicity, Hutu, Tutsi, Ganda, Igbo? Why did the fact that the majority of Rwandans were Christians make no difference to the Christians who readily killed their Tutsi brothers and sisters? To these and similar questions of African Christian identity we now turn—again, not in an abstract way, but in a way that highlights what my own journey as a Ugandan Catholic priest living in America, as a philosopher turned theologian, and as a scholar-practitioner has taught me about Christian identity in general and African Christian identity in particular.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from the chapter "On Being an African" in Who Are My People?: Love, Violence, and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here. All rights reserved.