We will explore the relationship between the sacraments of initiation and the transformation of personal identity. This relationship could be made clearer if people really took a new name at confirmation. The new personal identity conferred by baptism and confirmation is something our contemporaries still desire, or at least miss. How would we know that?

Some years ago, the British press discovered that a couple had secretly fled their suburban home in our Sceptered Isle, and taken on a new name and identity in South America. Our University chaplain was unable to fathom why reports about the discovery of the missing couple and their backstory occupied the front pages of the newspapers for days on end. I had to explain to the clueless fellow that many people harbor and delight in the idea of taking on a false identity and escaping their everyday lives as someone altogether different. Very many newspaper readers would like to turn up in Rio de Janeiro as someone else.

Indicating the conditions under which we must “serve somebody,” Bob Dylan observed, “you might be living in another country, under another name.” That is, you cannot hide from the human obligation to choose whether to serve God or mammon by changing your name. A new name might even be a way, not of evading being found out, but of metanoia. It could be a means through which one finds and embraces truth. Most people would like to take a new name and start over again. Catholic sacramental liturgy should give people this opportunity.

Four of the most outstanding TV series of our day show that “name-giving” could easily operate within Christian initiation rites at a deeper level than usually happens today. These ceremonies could be more symbolically satisfying if we reflected on what they tell us about “what’s in a name.” The two great Vince Gilligan productions, Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, Le Bureau des Legendes, and The Americans give us illustrations of the problem of names which both conceal and reveal personal identity. Fictions about fictions are thrilling particularly when they relate to personal identity. Striving to re-author one’s life is a doomed and dooming enterprise, but it appeals nonetheless.

Gilligan is a master of the theme of adopted name as a slow-burning degenerative mechanism. Walter White unleashes his inner super-villain when he adopts a fictive identity as Heisenberg, and his fictive “Heisenberg” identity allows him to achieve an authenticity he lacked as a high school teacher and also destroys him from within. The whole of the prequel, Better Call Saul describes how Jimmy McGill, failed lawyer, became the (literally) criminal lawyer, Saul Goodman. The journey of Jimmy into Saul is an inverted “Damascus type” conversion story. These stories show us that a name has its own personal intentionality and trajectory: as one is called and choses to call oneself, so one becomes. Could this help us to think about name-giving within initiation rites?

The careers of fictional undercover agents are interesting because of how the “concealing name” transforms personality. The Bureau in Le Bureau des Legendes is the French CIA, the DGSI. The “Legendes” of the title refer to the names taken on by agents on their mission: the agents undergo a quasi-religious absorption into their new identities, and yet, they must sit loose to them. The five seasons of this TV series depict the tragedy which ineluctably unfolds when one agent is pulled out of his mission in Syria, but refuses to return in full to his natural identity as Guillaume Debailly, and, instead, clings on to his invented identity as Paul Lefebvre.

As “Paul” he has fallen in love with the beautiful Nadia and he cannot relinquish this fictive identity because it is a true development of his personality, latching onto the truth of his identity. Le Bureau’s theme of the necessary but somewhat untruthful “office-identity” is reminiscent of The Americans. The Americans tells the tale of two Russian spies who have embedded themselves in suburban Washington DC in the 1970s, with elaborate invented false identities as Americans. As Elizabeth and Philip hoodwink their associations, the audience identifies not with their lies and betrayals, but with acting as a necessary part of social life.

The appeal of both Le Bureau and The Americans is a testimony to the experience of “role-dysphoria” which most people undergo regarding the truth of their names and social identity. We are fascinated by imposters like Elizabeth and Philip, because we experience pretense in the performance of our public roles. The more our culture emphasizes authenticity, the worse we feel about the necessary imposture of social role play.

The cultural emphasis on authenticity guarantees role-dysphoria, and role-dysphoria is not soluble by any social transition we can make: there is no social role in which we would not feel like fakers and imposters. The only way to find one’s identity is by playing a social role; introspection will not do the trick. And yet, because no social role fully fits, the struggle between social representation and authentic expression gives rise to identity dysphoria. When someone cannot see themselves in their socially given identities, they dream of escaping them and starting over.

It would probably be at the least a venial sin to flee one’s commitments and creditors and attempt to live out one’s days in Rio de Janeiro under an assumed name. Many people felt that Elizabeth and Philip deserved more condign punishment than the loss of their children and relegation to being themselves (together!) in a Moscow apartment. What The Americans’ showrunner called “story karma” is worked out with greater moral realism in The Bureau finale, where nearly every agent is exposed as an instrument in a machine that exploits and destroys their loves and their personalities. Only “Paul,” by following the intentional trajectory of his name and legend to its tragic end, protects his selfhood. Perhaps the script-writers consulted Book XIX of The City of God, or perhaps French culture will remember its Jansenism much longer than it recalls its Catholicism.

There is something hopelessly Romantic not only in “Paul’s” tragic love for Nadia, but in the spy’s determination to use every ounce of his tradecraft to hold onto his self against the group-think of the Bureau, which relentlessly subjects his personal good to their political objectives. This Romantic determination to preserve the self against the group ultimately rests on the Christian idea that the self is sacred, because it is given and not made, discovered and not constructed. We do have a secret, interior gifted identity, but the discovery and protection of that secret personal identity is a lifelong quest. So, our lives are in a sense the search for our true name, that is the name, which really corresponds. We need to be named for ourselves and we need to hear our real name on the lips of another who sees us for what we are.

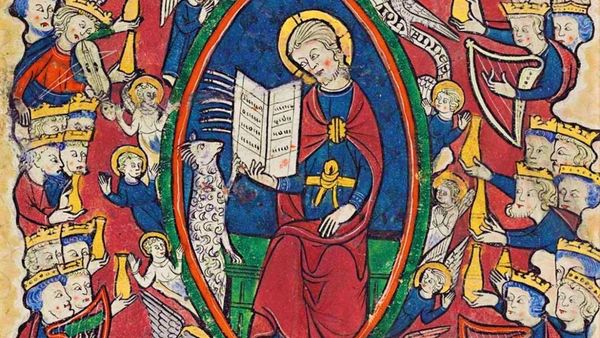

The Bible connects the act of faith with the giving of a name. In the Old Testament, God changes the name of Abram to Abraham, on account of his faith. In the New Testament, Simon’s confession of faith in Jesus as the Son of the living God is rewarded by Jesus changing his name to the “Rock” (Petros in Greek), “and upon this rock I will build my church” (Matt 16:13-20). The Aramaicism Cephas for Petros is a token of the authenticity of this Matthean pericope. It is like when one’s friends or classmates give one a nick-name that sticks, and sticks because it captures the reality. “Rocky” does not just represent Peter, but expresses his divine commission, the Church-founding project upon which the fisherman is impelled. The “given-name” is often a fond mistake, the nick-name, which comes later in life, exhibits the reality.

After being hurled to the ground and given his commission, Saul is not named Paul. Rather, later, as his mission to the Gentiles germinates, he adopts the Roman form of the Hebrew Saul, that is, Paul. “Paul” is a nominal symbol of his missionary orientation to Roman culture: Saul is called Paul from Acts 13:9 onward, as he adopts his new identity.

In the ancient Church in particular baptism took the form of an interrogation in which the bishop asked the candidate whether they believe in the Father, and in the Son, and in the Holy Spirit. After each affirmation, the candidate was dunked in the baptismal water. The subjective belief of the candidate is transformed into objective faith. Their subjective belief is being transformed through divine illumination into burning faith, as if the Burning Bush itself were to visit the human mind through the act of baptism. What happens in baptism is not a ratification of a faith that the candidate already holds but rather the metamorphosis of the subjective belief of the baptismal candidate into the theological virtue of faith.

At confirmation, the candidate already believes in Father, Son and Holy Spirit and comes to believe in them in and through the faith of the Church. Objective faith is translated into subjective and ecclesial faith just as the fire of the Holy Spirit at the first Pentecost translated all those many languages. So one is no longer a monoglot, stuck in the language of one’s own particular tribe or confined in one’s own private language, if there is such a thing (and I tend to think there is), but rather one speaks confidently in the universal, “Spirited” language of the faith of the Church.

The first gift of the sacraments of initiation is communication. The baptized person literally becomes a communicant. The baptized communicant does not have his own materially private language of belief in the Trinity taken away from him. Instead, that language is transformed into an objective spiritual language which everyone else can understand too.

The actual gift that comes with baptism is faith. This faith grows within us until, at confirmation, it becomes a subjective illumination of the mind. With baptism comes the objective faith, and with confirmation comes the completion, whereby objective faith has assimilated the subject into itself. It is through confirmation, and the gift of the Holy Spirit at confirmation, that we put on the mind of Christ with which to see reality.

It is because of the objectivity of the gift of faith that infant Baptism is treated as normative by many authors. At a time when it had become fashionable to be a convert, Bernanos boasted of his cradle Catholic status, as Hans Urs von Balthasar recounts it: “In a questionnaire he once filled out for his publisher, Plon, Bernanos entered: ‘Catholic since baptism, not even a convert!’” Or consider Étienne Gilson’s description of baptism in The Philosopher and Theology. Gilson is arguing that faith is the foundation for right reason in the Christian thinker. He begins by criticizing rationalist catechisms which do not just state in the first line that God exists but which give Sunday school arguments for the existence of God, arguments which children will eventually grow out of. He then proceeds to imply that in a sense he has been a believer from birth. This is what he writes:

No one is born a Christian, but a man born in a Christian family soon becomes one without having been consulted. He is not even aware of what is happening to him. At baptism, the child receives within himself a sacrament whose effects will decide his future in time and eternity. His godfather says the Creed for him and assumes for him obligations whose terms the child does not even understand, but which are no less binding for him . . . the Church considers him bound by them. When she will ask him later on, as she does every year, to “renew” the promises of baptism, the very same promises once made for him by someone else are those he is invited to make all over again. The grown man is free not to renew them, but there is a great difference between not belonging to a Church and explicitly refusing to belong to it. The non-baptized man is a pagan, the baptized man who refuses to honor the promises of baptism . . . is an apostate . . .

He continues:

Baptism is a sacrament; it is not in the Christian’s power not to have received its grace. Besides, the simplest of prayers addressed to God is a profession of faith in His existence. The life of prayer engages the child in a personal relationship with God and it never crosses his mind that his prayer could be without an object. The very names “God,” “Jesus,” “Mary” immediately bring real persons to his imagination. Since he is conversing with them, how could he doubt their existence? The Church sees to it that no Christian, however young, ever utters words that are meaningless to him. The young communicant is not interested in controversies about transubstantiation, but his devotion to the Eucharist goes straight to its true object. The consecrated host truly is for him the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, true God and true man, hidden to the eyes of the flesh, but present to the eyes of faith under the appearance of bread. His whole religion is given to him at once in this great sacrament . . . The child cannot be a doctor of the Church, but he can be a saint.

Gilson claims that the objectivity of the sacrament is so final, so foundational that the infant’s bawling, blind, and passive endurance of the sacrament is the best example, the best-case scenario so to speak. Baptism is a kind of project. It is intentional, and not in the sense of a purely inner motivation. Baptism is intentional in the sense of a relation that it sets up between the baptized subject, and its object, Christ. Baptismal faith is a “baptismal relation” between the baptized subject and Christ, where the subject is impelled, consciously or unconsciously, on a journey of discovery of who Christ is to be to him.

The baptized subject is set in an ineluctable relation of discovery in connection to Christ, which compels him to define his identity for Christ or against him. The problem of the baptized subject’s identity ineluctably involves an answer to the question, ‘Who do you say I am?’ Once baptized, the one who undergoes or passively suffers it has to find his identity within that question. And it is at Confirmation, and with the flames of the Holy Spirit to announce it, that this question is answered.

In the Christian baptismal rite, the person being baptized is given a name. The name is a token of a new character or a new personal identity. Even though I did not choose it, my name is in some sense “me,” myself into three words. To forget one’s name or to have one’s name replaced with a number is to lose oneself. To have a second set of names, like the undercover agents in Le Bureau des Legends, is to have several different and perhaps conflicting layers of identity. A name is not just an external “legend;” but rather, it seems to enter deeply into ourselves.

This is why it makes sense to think of Christian baptism as a conferring of identity. It makes sense to think of Christian baptism as the reception of our true name from Christ through the priest. If there were no dysphoria, we would not need to be named in order to find ourselves. This positive need for a name is answered in the baptismal act of naming.

At confirmation we bring along a new name which we ourselves have chosen, usually a saint’s name, so that our Christian identity can be ratified through an act of free decision. But this “name” that is taken at confirmation tends to be an optional and quickly forgotten “add on.” Years later, one may fondly recall that one took the name of Saint Edmund Campion at confirmation, but this has no connection with one’s subsequent public identity.

Instead of being a point of new beginning, confirmation is often the highest point in people’s religious lives, after which it is downhill all the way. And that is where it is not a mere social rigmarole. Far too many people are what they call “raised Catholic,” and then walk away from the faith in late adolescence. By “raised Catholic” they mean that they were given a saint’s name shortly after birth, in the ceremony which they do not remember, and that they later participated in Sunday school lessons after Mass that impressed them with the irredeemably infantile quality of their beliefs, picked up some good presents, maybe even cash, at confirmation, and later abandoned going through the motions. Their true and authentic rite of adulthood is not confirmation but the abandonment of the faith once professed. This way of doing things turns people into what Gilson calls apostates.

Adult confirmation is the best confirmation. The fruit of the confirmation of schoolchildren or adolescents is simply the crop of what Gilson called apostates. We are reaping the fruits of not allowing the Spirit to blow where it will, and deferring confirmation until the subject is up for it and requests it. We are treating confirmation too much like baptism, where faith is objectively conferred, and not enough like a real bringing to life within the subject of that objective faith given in infancy. I think one way of ensuring that confirmation is not an empty add-on to baptism, or a rite of adolescent passage, but the real sacrament of initiation for adults is to make confirmation the stage at which the Christian is given a new name.

I think that all Catholics should be confirmed in adulthood, that is at least over the age of 18, and that the confirmation ritual should include the giving of a new name. This name should not just be whispered to the Bishop and then set aside, but actually stick. Like Saul’s taking Paul, it should reflect one’s sense of one’s mission. As with Saul’s conversion into Paul, it should come long after one’s initial encounter with Christ. The confirmation name should be, not just a saint’s name as an add on but an actual and permanent change of name.

Obviously, the name we chose at confirmation can never be literally the same as the name we will receive at the end of time, written on a white stone (Rev 2:17): our very selves remain mysterious to all but God, and God alone knows our true name and calling. Any name we select for ourselves will fall pitifully and laughably short of the name God intends for us. But the mere fact of prayerfully discerning the new name and taking it for life implies a real conversion and change of life. Imagine if not just monks and nuns but all new Catholics took a new name and formally stuck with it. It might even throw a spanner in the machinations of the online offense archaeologists. I think the donation and registration of a new name at confirmation would give the sacrament the gravity it deserves.

Neither schoolchildren nor adolescents could take a new name for themselves at confirmation. Like marriage, the rite would have to be restricted to adults over the age of 18. I appreciate that this way of going about it prefers quality to quantity of confirmation candidates. But we have been going for quantity for generations with diminishing returns in the only terms that matter. The believing cradle Catholic adult is becoming as rare as the convert. Cradle Catholics and adult converts should be treated alike in the matter of confirmation. Both should replace the name the parents gave them, the given name, with a convert name, and with it a convert identity.

Today, whether you are in Hong Kong or in San Francisco or even in Rio de Janeiro, becoming a Catholic is a severely counter-cultural decision. It means stepping away from the culture in which one was raised. There is nothing sacrosanct or immaculate about church culture as such. A convert has to become new even with respect to the Christian culture in which they were raised. At the very least, they must take a personal decision to become a new man, as Paul put it, within that Church culture. It also means permanently standing apart from the culture in which one will live out one’s days. The new name represents this. The new name taken in adulthood symbolizes what Stanley Hauerwas long ago called the “resident alien” status of Christians. The taking of a new name is not a magical bullet which will keep the adult confirmand on the straight and narrow: many monks, brothers and nuns take new names and yet return to the lay state and their given names. The new name marks the weight of the project and enterprise upon which the confirmation candidate has embarked but it does not ensure the destination. Only the Holy Spirit can do that.

Of course, the confirmation candidate will come ruefully to observe the distance between the new name he takes for himself and his “real name,” given to him at the last judgment, engraved upon a white stone. He may come to regard his confirmation name as just so much straw, as Thomas came to see his theological writings. But only nitwits and numbskulls think that means it was not worth it for Thomas to write his Summas.