René Girard’s “hypothesis,” as he calls it himself, asserts that the sacred is produced by a mechanism of self-externalization that, in transforming violence into ritual practices and systems of rules, prohibitions, and obligations, allows violence to contain itself. In this view, the sacred is identified with a “good” form of institutionalized violence that holds in check “bad” anarchic violence. The desacralization of the world that modernity has brought about is driven by a kind of knowledge, or suspicion perhaps, that has gradually insinuated itself into human thinking: could it be that good and bad violence are not opposites, but actually the same thing; that, at bottom, there is no difference between them?

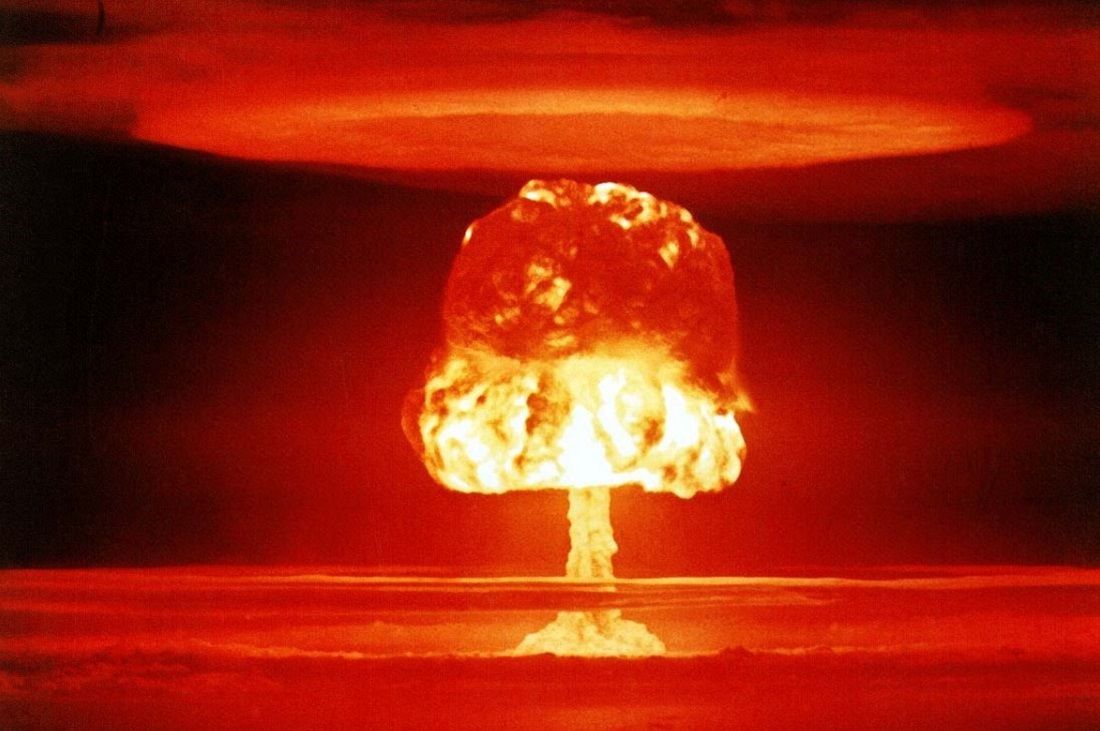

There is no doubt that we now know that “Satan casts out Satan,” as the Bible says; we know that evil is capable of self-transcendence, and by virtue of just this, is capable of containing itself within limits—and so, too, of averting total destruction. The most striking illustration is to be found in the history of the decades that made up the Cold War. Throughout this period, it was as though the bomb protected us from the bomb—an astonishing paradox that some of the most brilliant minds have sought to explain, with only mixed success. The very existence of nuclear weapons, it would appear, has prevented the world from disappearing in a nuclear holocaust. That evil should have contained evil is therefore a possibility, but plainly it is not a necessity, as the nuclear situation today shows us with unimprovable clarity. The question is no longer: why has an atomic war not taken place since 1945? Now the question has become: when will it take place in the future?

It used to be said of the atomic bomb, especially during the years of the Cold War, that it was our new sacrament. Very few among those who were given to saying this sort of thing saw it as anything more than a vague metaphor. But in fact there is a very precise sense in which nuclear apocalypse can be said to bear the same relation to strategic thought that the sacrificial crisis, in René Girard’s mimetic theory, bears to the human sciences: it is the absent—yet radiant—center from which all things emerge; or perhaps, to change the image, a black—and therefore invisible—hole whose existence may nonetheless be detected by the immense attraction that it exerts on all the objects around it.

In the section “Science and Apocalypse” of Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde (book 2, chapter 3), Girard makes important observations on what has been called in an improbable oxymoron, “nuclear peace.”[1] This, according to him, shows clearly that we are already living under the spell of the Book of Revelation. The Bomb has become like the “Queen of the world”; we live under Her protection, but we also know that Her destructive power is purely human. Girard writes, “In a world more and more desacralized, only the permanent threat of total and immediate destruction stops human beings from destroying one another. As always, violence is that which prevents the unleashing of violence" (Des choses cachées, 279). What is remarkable at this stage of his analysis is that Girard feels the need to tell us that nuclear peace is not the sign that the Kingdom of God is already with us (Des choses cachées, 281). He goes so far as to say that the “the power of destruction of the bomb, . . . under certain aspects, . . . functions in a way similar to the logic of the sacred" (Des choses cachées, 278–79). Thus, according to Girard himself, nuclear peace is a new form of the sacred informed by the knowledge that the power of destruction which threatens us with complete annihilation and, at the same time, protects us against that tragic end, comes from us and not from God.

That raises an important issue regarding the internal consistency of Girard’s anthropology of violence and the sacred. A central postulate of the theory is that the misrecognition (méconnaissance) of sacrificial mechanisms is a necessary condition for their functioning. The misrecognition issue is one of the major keystones in the edifice built up by Girard. Remove it and much of the theory of cultural evolution post Revelation—that is, the dynamics of modernity—is in serious danger of collapsing. Ante apocalypsis (before the Revelation), according to the theory, the participants in the collective victimage “know not what they do”—that may be the reason why they should be forgiven. They do not know their victim for what he is: a victim, the unlucky center of an arbitrary process of convergence. This misrecognition is not accidental, since it is an essential part of the mechanism. It is necessary to its proper functioning. The convergence of all against one rests on the common conviction that this one, the victim, carries an ultimate responsibility in the ongoing violence. The peace that follows the victim’s death confirms everyone in their previous belief.

If Christianity can be said to be “the religion of the end of religion,” it is because the Christian message slowly corrodes sacrificial institutions and progressively gives rise to a radically different type of society. The mechanism for manufacturing sacredness in the world has been irreparably disabled by the body of knowledge constituted by Christianity. Instead, it produces more and more violence—a violence that is losing the ability to self-externalize and contain itself. Thus, Jesus’s enigmatic words suddenly take on unsuspected meaning: “Do not think that I have come to bring peace on earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). The Christian revelation appears to be a snare, the knowledge it carries, a kind of trap, since it deprives humanity of the only means it had to keep its violence in check, namely the violence of the sacred. As Girard puts it,

Every advance in knowledge of the victimage mechanism, everything that flushes violence out of its lair, doubtless represents, at least potentially, a formidable advance for men in an intellectual and ethical respect but, in the short run, it is all going to translate as well into an appalling resurgence of this same violence in history, in its most odious and most atrocious forms, because the sacrificial mechanisms become less and less effective and less and less capable of renewing themselves. Humanity in its entirety already finds itself confronted with an ineluctable dilemma: men must reconcile themselves for evermore without sacrificial intermediaries, or they must resign themselves to the coming extinction of humanity (Des choses cachées, 150, 160, emphasis mine).

The fact that there has been neither any nuclear war nor, even more significantly, any direct conventional confrontation between nuclear powers since the advent of the atomic bomb, seems to give the lie to the assertion that méconnaissance is a necessary condition for the mechanisms of the sacred to function—if, indeed, the bomb is a new form of the sacred. What kind of sacred compatible with the end of misrecognition are we dealing with here? Girard sees the complexity of the issue but seems to be satisfied with the remark that “We are dealing here with a situation that is intermediary and complex" (Des choses cachées, 281). Unfortunately, he does not try to go further in the clarification of the “intermediary” status of our situation. That is what I will endeavor to do now.

I will draw on three major interpretations of the status of the bomb: a post-Heideggerian approach to be found in the work of German philosopher Günther Anders; a strategic analysis that starts with a game-theoretical account and is soon obliged to transcend it towards an heterodox conception of rationality; and, last but not least, René Girard’s anthropology. The fact that those three interpretations converge toward similar conclusions is deeply striking and constitutes the major result of my own research.

Blindness in the Face of Apocalypse

On August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb reduced the Japanese city of Hiroshima to radioactive ashes. Three days later, Nagasaki was struck in its turn. In the meantime, on August 8, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg provided itself with the authority to judge three types of crime: crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. In the space of three days, then, the victors of World War II inaugurated an era in which unthinkably powerful arms of mass destruction made it inevitable that wars would come to be judged criminal by the very norms that these victors were laying down at the same moment. This “monstrous irony” was forever to mark the thought of the most neglected German philosopher of the twentieth century, Günther Anders.

Anders was born on July 12, 1902, as Günther Stern, to German Jewish parents in Breslau (now the Polish city of Wroclaw). His father was the famous child psychologist Wilhelm Stern, remembered for his concept of Intelligence Quotient (or IQ). Günther worked in the 1930s as an art critic in Berlin. His editor, Bertolt Brecht, suggested that he call himself something different, and from then on he wrote under the name Anders (“Different” in German). This was not the only thing that distinguished him from others. There was also his manner of doing philosophy, which he had studied at Freiburg with Husserl and Heidegger. Anders once said that to write moral philosophy in a jargon-laden style accessible only to other philosophers is as absurd and as contemptible as a baker’s making bread meant only to be eaten by other bakers. He saw himself as practicing “occasional philosophy,” a kind of philosophy that “arises from concrete experiences and on concrete occasions.” Foremost among those “concrete occasions” was the conjunction of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, which is to say the moment when the destruction of humanity on an industrial scale entered the realm of possibility for the first time.

Anders seems not to have been very well liked, at least not by his first wife, Hannah Arendt, who had been introduced to him by their classmate at Freiburg, Hans Jonas—each of them a former student of Heidegger, as he was; each of them Jewish, as he was; each of them destined to become a more famous philosopher, and a far more influential one, than he would ever be. The memory of Günther Anders matters because he is one of the very few thinkers who have had the courage and the lucidity to link Hiroshima with Auschwitz, without in any way depriving Auschwitz of the sad privilege it enjoys as the incarnation of bottomless moral horror. He was able to do this because he understood (as Arendt herself did, though probably somewhat later) that even if moral evil, beyond a certain threshold, becomes too much for human beings to bear, they nonetheless remain responsible for it, and that no ethics, no standard of rationality, no norm that human beings can establish for themselves has the least relevance in evaluating its consequences.

It takes courage and lucidity to link Auschwitz and Hiroshima, because still today in the minds of many people—including, it would appear, a very large majority of Americans—Hiroshima is the classic example of a necessary evil. Having invested itself with the power to determine, if not the best of all possible worlds, then at least the least bad among them, America placed on one of the scales of justice the bombing of civilians and their murder in the hundreds of thousands and, on the other, an invasion of the Japanese archipelago that, it was said, would have cost the lives of a half-million American soldiers. Moral necessity, it was argued, required that America choose to put an end to the war as quickly as possible, even if this meant shattering once and for all everything that until then had constituted the most elementary rules of just war. Moral philosophers call this a consequentialist argument: when the issue is one of surpassingly great importance, deontological norms—so called because they express a duty to respect absolute imperatives, no matter what the cost or effects of doing this may be—must yield to the calculus of consequences. But what ethical and rational calculation could justify sending a million Jewish children from every part of Europe to be gassed? There lies the difference, the chasm, the moral abyss that separates Auschwitz from Hiroshima.

In the decades since, however, persons of great integrity and intellect have insisted on the intrinsic immorality of atomic weapons, in general, and the ignominy of bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in particular. In 1956 the Oxford philosopher and Catholic thinker Elizabeth Anscombe made an enlightening comparison that threw into stark relief the horrors to which consequentialist reasoning leads when it is taken to its logical conclusion. Let us suppose, she said, that the Allies had thought at the beginning of 1945 that, in order to break the Germans’ will to resist and to compel them to surrender rapidly and unconditionally, thus sparing the lives of a great many Allied soldiers, it was necessary to carry out the massacre of hundreds of thousands of civilians, women and children included, in two cities in the Ruhr. Two questions arise. First, what difference would there have been, morally speaking, between this and what the Nazis did in Czechoslovakia and Poland? Second, what difference would there have been, morally speaking, between this and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?[2]

In the face of horror, moral philosophy is forced to resort to analogies of this sort, for it has nothing other than logical consistency on which to base the validity of its arguments. In the event, this minimal requirement of consistency did not suffice to rule out the nuclear option nor to condemn it afterwards. Why? One reply is that because the Americans won the war against Japan, their victory seemed in retrospect to justify the course of action they followed. This argument must not be mistaken for cynicism. It involves what philosophers call the problem of moral luck. The moral judgment that is passed on a decision made under conditions of radical uncertainty depends on what occurs after the relevant action has been taken—something that may have been completely unforeseeable, even as a probabilistic matter.

Robert McNamara memorably describes this predicament in the extraordinary set of interviews conducted by the documentarian Errol Morris and released as a film under a most Clausewitzian title, The Fog of War (2003). Before serving as secretary of defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, McNamara had been an advisor during the war in the Pacific to General Curtis LeMay, who was responsible for the firebombing of sixty-seven cities of Imperial Japan, a campaign that culminated in the dropping of the two atomic bombs. On the night of March 9–10, 1945, alone, one hundred thousand civilians perished in Tokyo, burned to death. McNamara approvingly reports LeMay’s stunningly lucid verdict: “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” Another possible reply is that consequentialist morality served in this instance only as a convenient pretext. A revisionist school of American historians led by Gar Alperovitz has pleaded this case with great conviction, arguing that in July 1945, Japan was on the point of capitulation.[3] Two conditions would have had to be satisfied in order to obtain immediate surrender: first, that President Truman agree to an immediate declaration of war on Japan by the Soviet Union, and second, that Japanese surrender be accompanied by an American promise that the emperor would be allowed to continue to sit on his throne. Truman refused both conditions at the conference at Potsdam, a few days after July 16, 1945. On that day, the president received “good news.” The bomb was ready— as the successful test at Alamogordo had brilliantly demonstrated.

Alperovitz concludes that Truman sought to steal a march on the Soviets before they were prepared to intervene militarily in the Japanese archipelago. The Americans played the nuclear card, in other words, not to force Japan to surrender but to impress the Russians. In that case, the Cold War had been launched on the strength of an ethical abomination and the Japanese reduced to the level of guinea pigs, since the bomb was not in fact necessary to obtain the surrender. Other historians reckon that whether or not necessary, it was not a sufficient condition of obtaining a surrender.

The historian Barton J. Bernstein has proposed a “new synthesis” that departs from both the official and the revisionist accounts.[4] The day after Nagasaki, the war minister, General Korechika Anami, and the vice chief of the Naval General Staff, Admiral Takijiro Ōnishi, urged the emperor to authorize a “special attack [kamikaze] effort,” even though this would mean putting as many as twenty million Japanese lives at risk, by their own estimate, in the cause of ultimate victory. In that case, two bombs would not suffice. So convinced were the Americans of the need to detonate a third device, Bernstein says, that the announcement of surrender on August 14—apparently the result of chance and of reversals of alliance at the highest level of the Japanese government, still poorly understood by historians—came as an utter surprise. But Bernstein takes the argument a step further. Of the six options available to the Americans to force the Japanese to surrender without an invasion of the archipelago, five had been rather cursorily analyzed, singly and in combination, and then rejected by Truman and his advisors: continuation of the conventional bombing campaign, supplemented by a naval blockade; unofficial negotiations with the enemy; modification of the terms of surrender, including a guarantee that the emperor system would be preserved; awaiting Russian entry into the war; and a noncombat demonstration of the atomic bomb. As for the sixth option, the military use of the bomb, it was never discussed—not even for a moment: it was simply taken for granted. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed from the bomb’s very existence. From the ethical point of view, Bernstein’s findings are still more terrible than those of Alperovitz: dropping the atomic bomb, perhaps the gravest decision ever taken in modern history, was not something that had actually been decided.

These revisionist interpretations do not exhaust the questions that need to be asked. There are at least two more. First, how are we to make sense of the bombing of Hiroshima—and, more troubling still, of Nagasaki, which is to say the monstrously absurd determination to persist in infamy? Second, how could the consequentialist veneer of the official justification for these acts—that they were extremely regrettable, but a moral necessity just the same—have been accepted as a lawful pretext when it should have been seen instead as the most execrable and appalling excuse imaginable?

Not only does the work of Günther Anders furnish an answer to these questions, but it does so by relocating them in another context. Anders, a German Jew who had emigrated to France and then to America and then come back to Europe in 1950—everywhere an exile, the wandering Jew—recognized that on August 6, 1945, human history had entered into a new phase, its last. Or rather that the sixth day of August was only a rehearsal for the ninth—what he called the “Nagasaki syndrome.” The dropping of the first atomic bomb over civilian populations, once it had occurred, thereby introduced the impossible into reality and opened the door to more atrocities, in the same way that an earthquake is followed by a series of aftershocks. History became obsolete that day, as Anders put it. Now that humanity was capable of destroying itself, nothing would ever cause it to lose this “negative all-powerfulness,” not even a general disarmament, not even a total denuclearization of the world’s arsenals. Now that apocalypse has been inscribed in our future as fate, the best we can do is to indefinitely postpone the final moment. We are living under a suspended sentence, as it were, a stay of execution. In August 1945, Anders says, humanity entered into the era of the “reprieve” (die Frist) and the “second death” of all that had existed: since the meaning of the past depends on future actions, the obsolescence of the future, its programmed end, signifies not that the past no longer has any meaning, but that it never had one.[5]

To ascertain the rationality and the morality of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki amounts to treating nuclear weapons as a means in the service of an end. A means loses itself in its end as a river loses itself in the sea and ends up being completely absorbed by it. But the bomb exceeds all the ends that can be given to it, or found for it. The question whether the end justifies the means suddenly became obsolete, like everything else. Why was the bomb used? Because it existed. The simple fact of its existence is a threat, or rather a promise that it will be used. Why has the moral horror of its use not been perceived? What accounts for this “blindness in the face of apocalypse”? Because beyond certain thresholds, our power of doing infinitely exceeds our capacity for feeling and imagining. It is this irreducible gap that Anders called the “Promethean discrepancy.” Thus, Hannah Arendt, for example, was to diagnose Eichmann’s psychological disability as a “lack of imagination.” Anders showed that this is not the weakness of one person in particular; it is the weakness of every person when his capacity for invention, and for destruction, becomes disproportionately enlarged in relation to the human condition.

“Between our capacity for making and our capacity for imagining,” Anders says, “a gap is opened up that grows larger by the day.” The “too great” leaves us cold, he adds. “No human being is capable of imagining something of such horrifying magnitude: the elimination of millions of people.

The Paradox of Nuclear Deterrence: Away from Strategic Thinking, Back to the Sacred

A pacifist would say that surely the best way for humanity to avoid a nuclear war is not to have any nuclear weapons. This argument, which borders on the tautological, was irrefutable before the scientists of the Manhattan Project developed the atomic bomb. Alas, it is no longer valid today. Such weapons exist, and even supposing that they were to cease to exist as a result of universal disarmament, they could be recreated in a few months. Errol Morris, in The Fog of War, asks McNamara what he thinks protected humanity from extinction during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union permanently threatened each other with mutual annihilation. Deterrence? Not at all, McNamara replies: “We lucked out.” Twenty-five or thirty times during this period, he notes, humankind came within an inch of apocalypse.

I have tried in my own work to enlarge the scope of Günther Anders’s analysis by extending it to the question of nuclear deterrence. For more than four decades during the Cold War, the discussion of “mutual assured destruction” (MAD) assigned a major role to the notion of deterrent intention, on both the strategic and the moral level. And yet the language of intention can be shown to constitute the principal obstacle to understanding the logic of deterrence.

In June 2000 Bill Clinton, meeting with Vladimir Putin in Moscow, made an amazing statement that was echoed almost seven years later by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, speaking once again to the Russians. The antiballistic shield that we are going to build in Europe, they explained in substance, is only meant to defend us against attacks from rogue states and terrorist groups. Therefore be assured: even if we were to take the initiative of attacking you in a first nuclear strike, you could easily get through the shield and annihilate our country, the United States of America.

Plainly, the new world order created by the collapse of Soviet power in no way made the logic of deterrence any less insane. This logic requires that each nation expose its own population to certain destruction by the other’s reprisals. Security becomes the daughter of terror. For if either nation were to take steps to protect itself, the other might believe that its adversary considers itself to be invulnerable, and so, in order to prevent a first strike, hastens to launch this strike itself. It is not for nothing that the doctrine of mutually assured destruction came to be known by its acronym, MAD. In a nuclear regime, nations are at once vulnerable and invulnerable: vulnerable because they can die from attack by another nation; invulnerable because they will not die before having killed their attacker—something they will always be capable of doing, no matter how powerful the strike that will have brought them to their knees.

There is another doctrine, known as NUTS (Nuclear Utilization Target Selection), which calls for a nation to use nuclear weapons in a surgical fashion for the purpose of eliminating the nuclear capabilities of an adversary while protecting itself by means of an antimissile shield. It will be obvious that MAD and NUTS are perfectly contradictory, for what makes a type of weapon or vector valuable in one case robs it of much utility in the other. Consider submarine-launched missiles, which have imprecise trajectories and whose mobile hosts are hard to locate. Whereas nuclear-equipped submarines hold little or no theoretical interest from the perspective of NUTS, they are very useful—indeed, almost ideal—from the perspective of MAD since they have a good chance of surviving a first strike and because the very imprecision of their guidance systems makes them effective instruments of terror. The problem is the Americans say that they would like to go on playing MAD with the Russians and perhaps the Chinese, while practicing NUTS with the North Koreans, the Iranians, and, until a few years ago, the Iraqis. This obliged them to show that the missile defense system they had been hoping to build in Poland and the Czech Republic would be penetrable by a Russian strike while at the same time capable of stopping missiles launched by a “rogue state.”

That the lunacy of MAD, whether or not it was coupled with the craziness of NUTS, should have been considered the height of wisdom, and that it should have been credited with having kept world peace during a period whose return some people wish for today, passes all understanding. Few persons were at all troubled by this state of affairs, however, apart from American bishops—and President Reagan. Once again, we cannot avoid asking the obvious question: why?

For many years, the usual reply was that what is at issue here is an intention, not the carrying out of an intention. What is more, it is an intention of an exceedingly special kind, so that the very fact of its being formed has the consequence that the conditions that would lead to its being acted on are not realized. Since, by hypothesis, one’s enemy is dissuaded from attacking first, one does not have to preempt his attack by attacking first, which means that no one makes a move. One forms a deterrent intention, in other words, precisely in order not to put it into effect. Specialists speak of such intentions as being inherently “self-stultifying.”[6] But this plainly does no more than give a name to an enigma. It does nothing to resolve it.

No one who inquires into the strategic and moral status of deterrent intention can fail to be overwhelmed by paradox. What seems to shield deterrent intention from ethical rebuke is the very thing that renders it useless from a strategic point of view, since deterrent intention cannot be efficient without the meta-intention to act on it if the circumstances require doing so. Deterrent intention, like primitive divinities, appears to unite absolute goodness, since it is thanks to this intention that nuclear war has not taken place, with absolute evil, since the act of which it is the intention is an unutterable abomination.

Throughout the Cold War, two arguments were made that seemed to show that nuclear deterrence in the form of MAD could not be effective.[7] The first argument has to do with the noncredible character of the deterrent threat under such circumstances: if the party threatening a simultaneously lethal and suicidal response to aggression that endangers its “vital interests” is assumed to be at least minimally rational, calling its bluff—say, by means of a first strike that destroys a part of its territory—ensures that it will not carry out its threat. The very purpose of this regime, after all, is to issue a guarantee of mutual destruction in the event that either party upsets the balance of terror. What chief of state having in the aftermath of a first strike only a devastated nation to defend would run the risk, by launching a retaliatory strike out of a desire for vengeance, of putting an end to the human race? In a world of sovereign states endowed with this minimal degree of rationality, the nuclear threat has no credibility whatever. Jonathan Schell summarizes this argument beautifully: “Since in nuclear deterrence theory, the whole purpose of having a retaliatory capacity is to deter a first strike, one must ask what reason would remain to launch the retaliation once the first strike had actually arrived. It seems that the logic of the deterrence strategy is dissolved by the very event—the first strike—that it is meant to prevent. Once the action begins, the whole doctrine is self-canceling. It would seem that the doctrine is based on a monumental logical mistake: one cannot credibly deter a first strike with a second strike whose raison d’être dissolves the moment the first strike arrives.”[8]

Another, quite different argument was put forward that likewise pointed to the incoherence of the prevailing strategic doctrine. To be effective, nuclear deterrence must be absolutely effective. Not even a single failure can be allowed, since the first bomb to be dropped would already be one too many. But if nuclear deterrence is absolutely effective, it cannot be effective. As a practical matter, deterrence works only if it is not 100 percent effective. One thinks, for example, of the criminal justice system: violations of the law must occur and be punished if citizens are to be convinced that crime does not pay. But in the case of nuclear deterrence, the first transgression is fatal.

The most telling sign that nuclear deterrence did not work is that it did nothing to prevent an unrestrained and potentially catastrophic arms buildup. If indeed it did work, nuclear deterrence ought to have been the great equalizer. As in Hobbes’s state of nature, the weakest nation— measured by the number of nuclear warheads it possesses—is on exactly the same level as the strongest, since it can always inflict “unacceptable” losses, for example by deliberately targeting the enemy’s cities. France enunciated a doctrine (“deterrence of the strong by the weak”) to this effect. Deterrence is therefore a game that can be played—indeed, that must be able to be played—with very few armaments on each side.

Belatedly, it came to be understood that in order for deterrence to have a chance of succeeding, it was absolutely necessary to abandon the notion of deterrent intention. The idea that human beings, by their conscience and their will, could control the outcome of a game as terrifying as deterrence was manifestly an idle and abhorrent fantasy. In principle, the mere existence of two deadly arsenals pointed at each other, without the least threat of their use being made or even implied, is enough to keep the warheads locked away in their silos.

This solution came with a name: existential deterrence. The intention or threat to retaliate and launch a counterattack that will lead to the Apocalypse is said to be the problem. Well, let us get rid of the intention. A major philosopher, Gregory Kavka, has said, “The existence of a nuclear retaliatory capability suffices for deterrence, regardless of a nation’s will, intentions, or pronouncements about nuclear weapons use.” A second major philosopher, David K. Lewis, similarly puts it, “It is our military capacities that matter, not our intentions or incentives or declarations.” If deterrence is existential, it is because the existence of the weapons alone deters. Deterrence is inherent in the weapons because “the danger of unlimited escalation is inescapable.” As Bernard Brodie put it in 1973, “It is a curious paradox of our time that one of the foremost factors making deterrence really work and work well is the lurking fear that in some massive confrontation crisis it may fail. Under these circumstances one does not tempt fate.”[9] The kind of rationality at work here is not a calculating rationality, but rather the kind of rationality in which the agent contemplates the abyss and simply decides never to get too close to the edge. As Lewis says, “You don’t tangle with tigers—it’s that simple.”

The probability of error is what makes deterrence effective. But error, failure, or mistake is not strategic here. It has nothing to do with the notion that a nation, by irrationally running unacceptable risks, can limit a war and achieve advantage by inducing restraint in the opponent. Thomas Schelling popularized this idea—known as the “rationality of irrationality” theory—in his landmark Strategy of Conflict, published in 1960. Here, by contrast, the key notion is “Fate.” The error is inscribed in the future. In other terms, the game is no longer played between two adversaries. It takes on an altogether different form. Neither is in a position to deter the other in a credible way. However, both want and need to be deterred. The way out of this impasse is brilliant. It is a matter of creating jointly a fictitious entity that will deter both at the same time. The game is now played between one actor, humankind, whose survival is at stake, and its double, namely its own violence exteriorized in the form of fate. The fictitious and fictional “tiger” we’d better not tangle with is nothing other than the violence that is in us but that we project outside of us: it is as if we were threatened by an exceedingly dangerous entity, external to us, whose intentions toward us are not evil, but whose power of destruction is infinitely superior to all the earthquakes or tsunamis that Nature has in store for us. Günther Anders and Hannah Arendt were right: we are living under a new regime of evil—an evil without harmful intent.

Heidegger famously said, “Only a God can still save us." In the nuclear age, this (false) God is the self-externalization of human violence into a nuclear holocaust inscribed in the future as destiny. This is what the fictitious tiger stands for. In this light, to say that deterrence works means simply this: so long as one does not recklessly tempt the fateful tiger, there is a chance that it will forget us—for a time, perhaps a long, indeed a very long time; but not forever. From now on, as Günther Anders had already understood and announced from a philosophical perspective at the antipodes of rational choice theory, we are living on borrowed time.

In his Memoirs, Robert McNamara asserts that several dozen times during the Cold War humanity came ever so close to disappearing in a radioactive cloud. Was this a failure of deterrence? Quite the opposite: it is precisely these unscheduled expeditions to the edge of the black hole that gave the threat of nuclear annihilation its dissuasive force. “We lucked out,” McNamara says. Quite true—but in a very profound sense it was this repeated flirting with apocalypse that saved humanity. Those “near-misses” were the condition of possibility of the efficiency of nuclear deterrence. Accidents are needed to precipitate an apocalyptic destiny. Yet unlike fate, an accident is not inevitable: it can not occur.

The key to the paradox of existential deterrence is found in this dialectic of fate and accident: nuclear apocalypse must be construed as something that is at once necessary and improbable. But is there anything really new about this idea? Its kinship with tragedy, classical or modern, is readily seen. Consider Oedipus, who kills his father at the fatal crossroads, or Camus’s “stranger,” Meursault, who kills the Arab under the blazing sun in Algiers—these events appear to the Mediterranean mind both as accidents and as acts of fate, in which chance and destiny are merged and become one.

Accident, which points to chance, is the opposite of fate, which points to necessity; but without this opposite, fate cannot be realized. A follower of Derrida would say that accident is the supplement of fate, in the sense that it is both its contrary and the condition of its occurring.

If we reject the Kingdom—that is, if violence is not universally and categorically renounced—all that is left to us is a game of immense hazard and jeopardy that amounts to constantly playing with fire: we cannot risk coming too close, lest we perish in a nuclear holocaust; nor can we risk standing too far away, lest we forget the danger of nuclear weapons. In principle, the dialectic of fate and chance permits us to keep just the right distance from the black hole of catastrophe: since apocalypse is our fate, we are bound to remain tied to it; but since an accident has to take place in order for our destiny to be fulfilled, we are kept separate from it.

Notice that the logical structure of this dialectic is exactly the same as that of the sacred in its primitive form, as elucidated by Girard. I am not speaking of an analogy here. It is the very same thing. One must not come too near to the sacred, for fear of causing violence to be unleashed; nor, however, should one stand too far away from it, for it protects us from violence. I repeat, once again: the sacred contains violence, in the two senses of the word.

There is a fundamental difference, though, between the sacred embodied in nuclear deterrence and the old sacred. We the Moderns know that the wild cat is a ruse, an artifice, an artful stratagem. We pretend to believe that it is real in the same way that we pretend to believe that the story we are being told or shown is true. This “suspension of disbelief ” is essential for fiction to bring about real effects in us and the world.[10]

Nuclear deterrence in its existential interpretation appears to be a self-reflexive, self-organized, self-externalized social system—neither blind, spontaneous collective phenomenon nor formal, carefully crafted set of procedures as in a ritual. It is indeed, as Girard wrote, an “intermediary case.” At the very least, it shows that the mechanisms of the sacred are perfectly compatible with a good measure of connaissance—that is, of self-knowledge

The Good News in Reverse: The End of Hatred and Resentment

It is probably owing to the influence of Christianity that evil has come to be most commonly associated with the intentions of those who commit it. And yet the evil of nuclear deterrence in its existential form is an evil disconnected from any human intention, just as the sacrament of the bomb is a sacrament without a god. In this context, worse news than the imminent end of hatred and resentment cannot be imagined.

In 1958, Günther Anders went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to take part in the Fourth World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. After many exchanges with survivors of the catastrophe, he noted in his diary, “Their steadfast resolve not to speak of those who were to blame, not to say that the event had been caused by human beings; not to harbor the least resentment, even though they were the victims of the greatest of crimes—this really is too much for me, it passes all understanding.” And he adds, “They constantly speak of the catastrophe as if it were an earthquake or a tidal wave. They use the Japanese word, tsunami.”[11]

The evil that inhabits the nuclear peace is not the product of any malign intention. It is the inspiration for passages of terrifying insight in Anders’s book, Hiroshima Is Everywhere, words that send a chill down the spine: “The fantastic character of the situation quite simply takes one’s breath away. At the very moment when the world becomes apocalyptic, and this owing to our own fault, it presents the image . . . of a paradise inhabited by murderers without malice and victims without hatred. Nowhere is there any trace of malice, there is only rubble.”[12] And Anders prophesies that “no war in history will have been more devoid of hatred than the war by tele-murder that is to come. This absence of hatred will be the most inhuman absence of hatred that has ever existed; absence of hatred and absence of scruples will henceforth be one and the same.”[13]

Violence without hatred is so inhuman that it amounts to a transcendence of sorts—perhaps the only transcendence yet left to us.

Editorial Statement: This excerpt comes from Apocalypse Deferred: Girard and Japan, ed. Jeremiah L. Alberg. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. Excerpts from other ND Press titles can be found here.

[1] René Girard, Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde (Paris: B. Grasset, 1978). All English translations are mine.

[2] G. E. M. Anscombe, “Mr. Truman’s Degree,” in Collected Philosophical Papers, vol. 3, Ethics, Religion, and Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1981), 62–71.

[3] Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth (New York: Knopf, 1995).

[4] Barton J. Bernstein, “Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory,” Diplomatic History 19, no. 2 (March 1995): 227–73.

[5] Günther Anders, Die Atomare Drohung (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1981).

[6] Gregory Kavka, Moral Paradoxes of Nuclear Deterrence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

[7] See the excellent synthesis of the debate by Steven P. Lee, Morality, Prudence, and Nuclear Weapons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[8] Jonathan Schell, The Fate of the Earth (New York: Knopf, 1982), 307.

[9] Bernard Brodie, War and Politics (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 370–71.

[10] “Fiction” comes from the Latin fingere, to make up, to make believe, to invent, to feign (and not from facere, to make, which gave “fact”).

[11] Günther Anders, Hiroshima ist überall (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1982), 84–85.

[12] Ibid., 87.

[13] Ibid., 114.