In “Truman’s Terrible Choice, 75 Years Ago”, George Weigel has defended the use of the atomic bomb against the populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the basis that it “saved millions, even tens of millions, of lives.” He acknowledges that this kind of utilitarian ethical calculus was rejected by Saint Pope John Paul II in Veritatis splendor but maintains that President Truman made the “correct choice.”

Professor John Keown and Professor Edward Feser have pointed out that Weigel here stands in direct contradiction to the moral teaching of the Catholic Church. However, a feature that has not been highlighted in these exchanges, neither by Weigel nor his critics, is that, while many Catholics in the United States supported these actions at the time, by attacking Nagasaki they were targeting the most important center of Catholic life in Japan. It was a massacre of Christians and on the very site of a previous act of mass Christian martyrdom. This does not change the moral character of the atrocity but it shows this act was also a wound inflicted on the body of Christ.

Weigel’s claim that using the atomic bomb saved millions of lives is impossible to demonstrate. We do not know, for example, the potential effect of the Soviet Union declaring war on Japan on 8 August 1945. We do not know what would have happened had the allies not insisted on unconditional surrender, for example had the allies given some assurance in advance that the Emperor could remain in place. It was the Emperor’s decisive intervention that brought the war to an end and we do not know if or when this may have happened in an alternative history. Nevertheless, even on the supposition that the deliberate massacre of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki did shorten the war, these actions do not for that reason cease to be massacres.

The atomic bombs destroyed and were intended to destroy entire areas together with their populations with the aim of, in Weigel’s words, “shocking Japan into surrender.” The dropping of two bombs demonstrated both the destructive force of this new weapon and, crucially, the willingness of the President to use this weapon, repeatedly, against centers of population in Japan. The aim of these attacks, as Weigel acknowledges, was not to degrade Japanese military capability prior to an American invasion but was “to stun Japanese politicians into recognizing that the entire nation would be destroyed if they did not . . . capitulate.” They were acts of awe and terror.

The destruction of centers of population as a means to put pressure on politicians falls squarely within the definition of a war crime and would easily be recognized as a war crime had the actions been taken by Nazi Germany against the population of cities in France or Poland. These actions would not have been seen simply as aggressive military actions and as wrong because the war itself was wrong. The use of a weapon of mass destruction against an entire city, with its schools and hospitals and children and sick, is always indiscriminate but where the aim is terror the deaths of the civilians are not collateral damage. The death toll is part of what makes the weapon terrifying and the threat credible. Had such terrible actions been taken by the losing side they would, without doubt, have been added to the list of crimes against humanity for which those responsible were put on trial. In the words of Gaudium et spes:

Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities or extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.

The article by Weigel aims to exonerate the President. He was not “a moral monster, the equivalent of Stalin, Hitler, and the Japanese militarists.” This is hardly a discriminating test. It would exonerate most murderers. In contrast, the decision to destroy whole cities along with their civilian populations was reason enough for the great Catholic philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe to object to the proposal that Oxford University confer an honorary degree on Mr. Truman. She says in the 1957 pamphlet “Mr. Truman’s Degree”:

The Censor of St. Catherine’s had an odious task. He must make a speech which should pretend to show that a couple of massacres to a man’s credit are not exactly a reason for not showing him honor . . . The defense, I think, would not have been well received at Nuremberg.

The title of Weigel’s article “a terrible choice” seems to imply that Truman showed moral courage by taking the decision to destroy two cities lest the entire nation perish. Anscombe expresses the same suggestion in this way “Mr. Truman was [thought to be] brave because, and only because, what he did was so bad.” However, she argues that, even on its own terms, this reasoning is unsound, “Given the right circumstances . . . a quite mediocre person can do spectacularly wicked things without thereby becoming impressive.” Going further, and putting these events in a theological context, we should perhaps consider whether it is right to make Truman himself the focus of our concern. Even to consider him as mediocre may be to give him too much consideration. The theological significance of this story lies elsewhere.

In recounting notorious crimes or massacres it is frequently the criminal who is celebrated. To be infamous is to be famous. The victim, in contrast, if not forgotten entirely, is always secondary to the story of the monster. In this way the victim is harmed twice, by the crime itself and by his or her erasure from the story. In contrast, the story of the Gospels is not, in the first place a story about Herod as a slaughterer of the innocent, or about Caiaphas as a moral sophist, or about Pontius Pilate and his troubled conscience. The focus of the story is not the rulers of this world but is the victim, the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.

A Christian reading of the terrible deeds carried out against the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should focus not on the person of the American President but on the people of those cities. For this is where Christ is to be found in this story. This is true of all victims but it is easier to see in some cases than others and, in a Catholic context, it is perhaps easier to see if we focus not on the first bomb, on Hiroshima, but on the second bomb, a massacre carried out almost as an afterthought on the city of Nagasaki. This is because Nagasaki was already a city of martyrs.

Saint Francis Xavier arrived in the West of Japan in the 1540s and traveled through what is now Nagasaki prefecture. The mission was very successful but when Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified Japan he became suspicious of foreign influence and issued decrees restricting the practice of Christianity and expelling missionaries from Japan. On 5 February 1597 Saint Paul Miki, a Jesuit seminarian, and twenty-five companions, mostly third order Franciscans, were crucified at Nagasaki.

By 1630 virtually all public expression of Christianity had been eradicated from Japan. However, when Catholic missionaries returned to Japan they found in and around Nagasaki hidden Christians Kakure Kirishitan who had kept elements of the faith alive for three and a half centuries with no priests and no sacraments. Many of these hidden Christians returned to the fold and became the core of a Catholic community in Urakami, an area in the North of Nagasaki.

Saint Maximilian Kolbe ministered there in the 1930s, before his return to Poland and his own martyrdom, a detail used as the basis of a short story, “Japanese in Warsaw,” by the Catholic novelist Shusaku Endo. Kolbe estimated that in his day, out of a population of 80 million, less than 100,000 Japanese were Catholics but of these 60,000 were in Nagasaki. When St Mary’s Cathedral in Urakami was completed in 1925 it was the largest Christian structure not just in Japan but in the whole Asia-Pacific region.

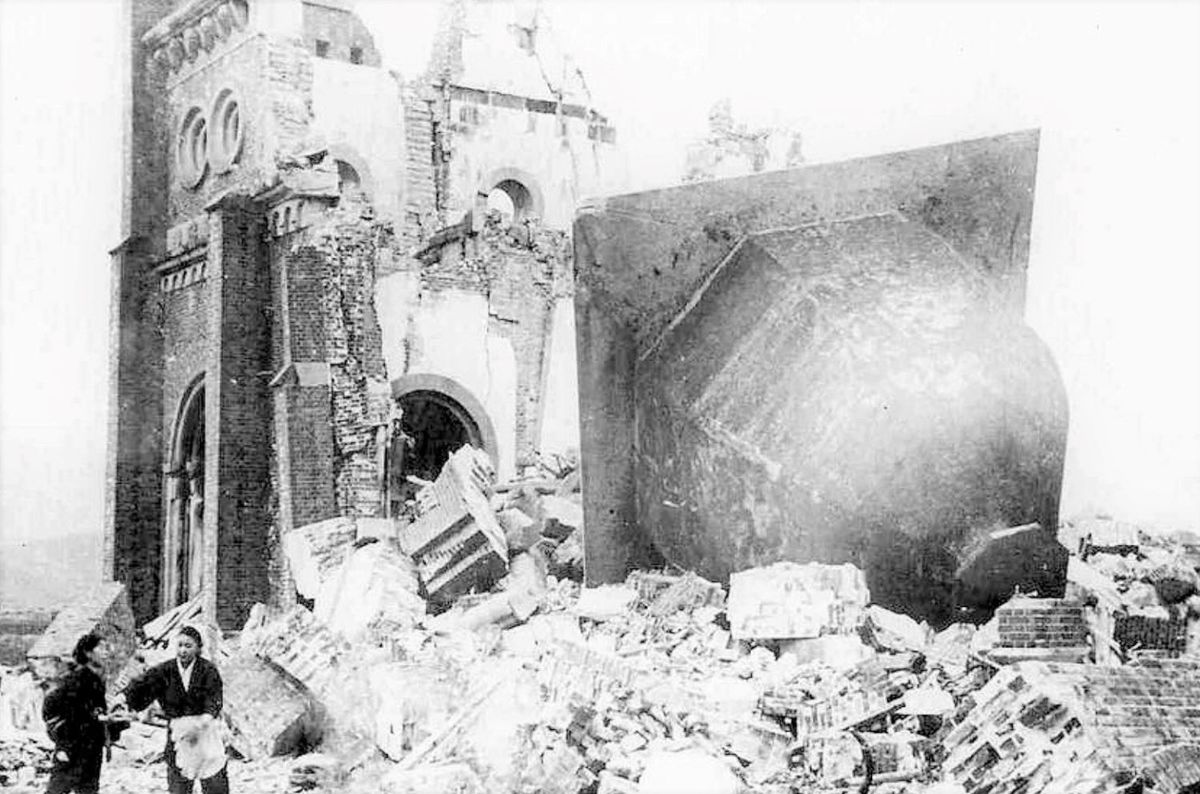

It was in this Cathedral in this city that the faithful had gathered on 9 August 1945 in preparation for the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. At 11AM, the second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” was detonated over Urakami only 500 meters from the Cathedral. The Cathedral was destroyed instantly and those who were praying were buried beneath the rubble. In total, somewhere between 40,000 and 80,000 people died in Nagasaki that day of whom only 150 were Japanese soldiers.

For at least some, their Catholic faith helped them to bear this ordeal. The Catholic doctor, Nagai Takashi who survived and tended the wounded at Hiroshima and Nagasaki described Nagasaki as “a whole burnt offering on the altar of sacrifice, atoning for the sins of all the nations during World War II.” In Endo’s words, “in the midst of the nuclear wilderness [Nagai] kept his heart in tranquility and peace, neither bearing resentment to any man nor cursing God.” Urakami Cathedral has been rebuilt by the people of Nagasaki. One item that remains from the original Cathedral is the head of a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary and every year on 9 August this charred head is carried in procession while prayers are offered for peace among nations.

The patient endurance of these massacres and the prayers of the faithful in Nagasaki call our attention to the humanity of those afflicted. In the words of Pope Francis, speaking at the Atomic Bomb Hypocenter Park in Nagasaki, “The damaged cross and statue of Our Lady recently discovered in the Cathedral of Nagasaki remind us once more of the unspeakable horror suffered in the flesh by the victims of the bombing and their families.” The face of the victim is always the face of Christ, and this is true of Hiroshima not less than Nagasaki, but it is perhaps easier to recognize when the murder happens in a Cathedral.