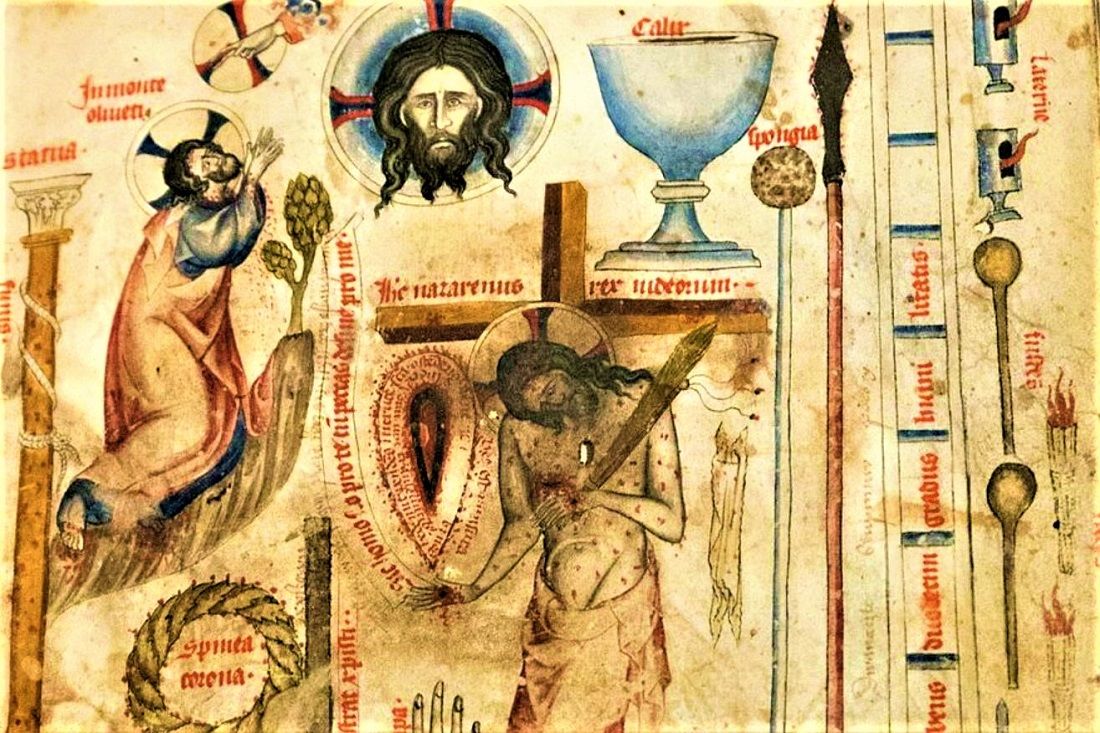

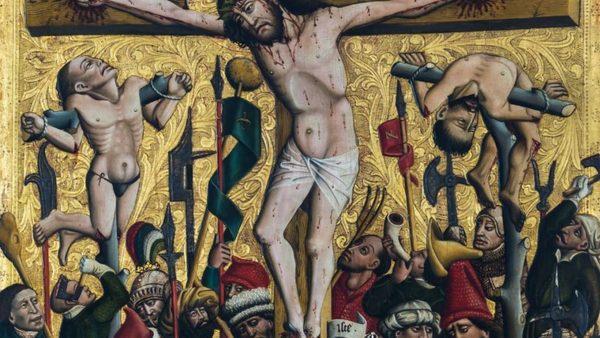

It is common to come across internet articles, television documentaries, or advertisements for books in the days and weeks preceding Easter detailing scientifically the nature and extent of the sufferings experienced by Christ during his Passion. From these you graduate from a notional apprehension of the sufferings of Christ understood abstractly and instead begin to grasp his Passion more realistically and painfully. For example, one might read of the tremendous suffering that Christ endured while his hands and feet were nailed to the Cross, which would have pierced a number of major nerves, sending waves of excruciating pain up and down his limbs. Each and every breath on the Cross would have become more and more difficult and agonizing, since to breathe while nailed to the Cross entailed using the nails in his wrists as leverage against which to lift his body to inhale and exhale. Or, to use another example, some scientists estimate that Christ would have lost anywhere from a quarter to a third of his blood supply by being scourged at the pillar, potentially sending his body into shock. If you adhere to Christian orthodoxy, as opposed to the bodiless—and, thus, not really human—Christ of the Gnostics, then it is simply common knowledge that Christ suffered physically at the hands of others and so for this reason science can tell us much about the nature and extent of that suffering.

So much for the bodily suffering of Christ at the hands of his Roman aggressors, but what is one to make of the suffering that would result from a disease or a virus? Is it fitting or impious to think that Christ suffered not only from the torture inflicted during his execution but also throughout his life from illnesses, thirst, hunger, and the like, as does the rest of the human race?

Thomas Aquinas, the “Common Doctor” of the Church, speaks of the “why” and the nature of the bodily suffering of Christ in his Summa Theologiae III Question 14 Article 1. Here, he offers three reasons for the fittingness of the Son of God’s assumption of the defects and infirmities that pertain to the body as a result of the sin of Adam, which includes the sufferings experienced through the body. The first reason has to do with the satisfaction of human sin, which—by taking upon himself the punishment due to mankind because of the sin of Adam, namely, the defects of the body such as “death, hunger, thirst, and the like”—is fitting according to the purpose of the Incarnation that he should assume these penalties incurred through sin than not. The second reason for the fittingness of Christ’s assumption of bodily defects has to do with the believability of his Incarnation. Since the Incarnation entails the Son’s full participation in human nature so as to be like us in every way except sin, Thomas writes that Christ assumed the defects belonging to human nature in its current unredeemed state so as to more readily convince others of his full humanity. Finally, Thomas writes that Christ assumed the defects of the body and suffered accordingly in order to provide an example of patience amidst suffering and trial.

These three reasons, taken at a glance, can be summed up in the following way: Christ took upon himself the possibility of death, hunger, thirst, and other such bodily sufferings for the sake of satisfaction, convincibility, and exemplarity. None of these three reasons, or any other reasons for that matter, necessitate that Christ was forced or constrained into assuming the bodily defects of man, since these defects follow upon a sinful human nature, which Christ did not have, as he writes in ST III Q. 14 Art. 3. Instead, Christ willingly chose to assume such bodily defects for, according to Thomas at least, the reasons mentioned above. What Thomas has spoken of above, however, pertains to the possibility of death, hunger, thirst, and “the like,” which he later clarifies to mean those defects that John Damascene calls “natural and indetractible passions.” “Natural,” here, means that these defects follow upon what is common to human nature in its fallen state, and “indetractible,” here, means that those defects imply no imperfection of knowledge or grace.

So, for Thomas, Christ assumed those bodily defects which “flow from the common sin of the whole nature” and are “not incompatible with the perfection of knowledge and grace.” The examples that he provides of such defects are the possibilities of death, hunger, thirst, and such things like these (a sunburn, perhaps, from being exposed too long to the sun without the proper SPF protection), result from both a lack of original justice and the natural corruptibility of the human body, which—had human nature not lost the grace of original justice—would have been prevented from such corruption. The sufferings of the body, however, extend far beyond such things as hunger, thirst, and other defects of this nature, or even the possibility of death if one is scourged and crucified. What are we to make of the question of whether it was fitting for Christ to suffer from any one of the whole gamut of human diseases and illnesses? This is the heart of the question that we are interested in answering here with the help of insights from modern biology.

For Thomas, such diseases as leprosy, epilepsy, and “the like” do not flow merely from the common human nature on account of the loss of original justice by Adam, but, instead, he considers defects of this nature to be the result of either the fault of the individual or a defect in the formative power of the particular person who contracts it, in addition to the natural corruptibility and passibility of the body that corresponds to mankind’s fallen state. Thomas believes, in other words, that diseases are not simply the result of the loss of original justice but stem from either a perverse use of one’s free will or an imperfection inherent in one’s bodily development.

Thomas provides an example of such a failure to act rightly as “inordinate eating,” but I think other examples frequently cited today could also be mentioned, such as a lack of exercise, an excessive use of alcohol or tobacco, and drug use, that is, basically any malady that results from one’s poor decision making. However, since Christ was perfect in knowledge, grace, and action, as mentioned above, by virtue of his soul being assumed by the Word of God, he did not and could not have committed such particular faults that lie behind such defects, and so he could not have contracted such maladies. So, in Thomas’s estimation, it is incorrect to suggest that Christ suffered from such diseases as type 2 diabetes, obesity from a poor diet and eating habits, lung cancer from excessive tobacco use, liver disease from alcohol abuse, or neurological disorders that result from drug abuse, since these diseases and others like them are the result of an individual man’s faults, and Christ committed no such faults.

But, what about those diseases that result from an imperfection of man’s formative power? Is it correct to assume that Christ suffered from such diseases as these? Thomas does not provide much clarification on what it means to have an imperfection of the formative power; however, he does mentioned that Christ could not have suffered such an imperfection because his flesh was conceived by the Holy Spirit, who in his infinite wisdom and power could not err or fail. So, it is reasonable to surmise from Thomas’s explanation that an imperfection of one’s formative power is a reference to those defects that result neither from one’s choice nor from external agents but are simply a defect inherent within the body itself, which differs from person to person and is not itself an aspect of fallen human nature as such since all do not experience the same illnesses. According to Thomas’s thought and in light of our present day medical knowledge, Christ could not have suffered from those diseases that are simply manifestations or outgrowths of an imperfection inherent within a given person’s genetic code, for example, which could potentially manifest itself in any number of ways, depending on the specifics of the defect. Thus, Christ could not have suffered from such diseases as epilepsy, type 1 diabetes, certain forms of rheumatism, leukemia, and others like this, precisely because his body was perfectly healthy in every way.

Operating from the knowledge available to him in his 13th century context, Thomas thinks that, while Christ could have suffered from hunger and thirst, as well as at the hands of the Roman guards, he could not have experienced suffering from diseases or viruses, whether it be epilepsy, leprosy, or the flu, since all bodily defects other than the ones mentioned above, are the result of either a given person’s poor choices or an imperfection of the formative power. Thomas is not alone in his conclusion. Athanasius, for example, writes in his On the Incarnation that, whereas humans suffer diseases and die because of the weakness of their nature, Christ “is not weak, but the Power of God, and the Word of God, and himself Life” and, therefore, “it was neither fitting for the Lord to be ill, he who healed the illnesses of others, nor again for the body to be weakened, in which he strengthened the weaknesses of others.”[1]

What, however, is one to make of such speculative musings, especially those of Thomas Aquinas, in the light of modern biology? For starters, whereas Thomas distinguished between those defects that are the result of sharing in the common, fallen human nature (such as thirst and hunger) and those defects that result from poor decision-making (such as type 2 diabetes or smoking-induced lung cancer), or the imperfections of one’s formative powers (such as epilepsy or type 1 diabetes), modern biologists can also distinguish between those same bodily defects that Thomas identified, broadly speaking, and another grouping, namely, those diseases that result from the harmful activity of foreign bacteria or viruses (such as leprosy, bacterial infections, a cold, or the flu). It is the new awareness of this third grouping of causes of certain diseases of which consists the great advantages and insights of present-day biology when re-considering the possible sufferings experienced by Christ.

Diseases that result from bacterial infection or viruses result neither from poor decision-making nor from a defect intrinsic to one’s body. Instead, such diseases as these are more akin to wounds inflicted by the Roman guards during Christ’s Passion. What both of these instances of suffering have in common is that they each result from afflictions that are caused by agents external to the healthy human body. A virus, for example, is widely recognized by biologists and medical professionals as a certain type of foreign entity that has invaded the human body and is not simply a defect of it due to either an inherent imperfection or one’s unhealthy habits. Instead, a virus is a substance in its own right with its own unique set of DNA that enters the body and attempts to replicate its DNA by hijacking the normal DNA replication of its host’s cells. Consequently, a normally functioning, healthy bodily reaction to such an invasive, foreign agent is to fight against the intruder by a variety of immune responses, such as the deployment of white blood cells, vomiting, swollen glands, developing a fever, and other such symptoms. All of these responses entail a healthy body’s response to the presence of harmful, foreign substances that, each in their own way, negatively affect one’s body and cause potentially life-threatening damage if not combated properly and in a timely manner.

What is important to recognize here is that such bacterial infections and viruses are neither imperfections of the body itself nor the result of poor decision making per se, but are instead themselves foreign aggressors similar to a human adversary. Likewise, the sufferings experienced as the result of bacterial infections and viruses, while perhaps different in kind from blunt trauma, share the important commonality that both result from one’s lived experience in the world as a response to the actions of either other things or people. Furthermore, Scripture attests to the fact that Christ’s body registered the suffering experienced at the hands of his torturers, which itself demonstrates the proper functioning of the nervous system. So, it is also reasonable to assume that his body reacted appositely to the tearing open of its flesh from the nails and thorns through the constriction of his capillaries, veins, and arteries, so as to prevent death from blood loss. Therefore, it seems equally reasonable to think that Christ’s body reacted as any healthy human body would to the presence of harmful bacteria or viruses. To think that Christ’s body not only could have struggled against such intra-bodily foreign agents, but also should have, if the situation presented itself, is simply fitting and appropriate to the workings of a healthy body. To think that Christ experienced such suffering at the hands of those diseases that pertain to bacterial infections and viruses is not only possible but is altogether fitting if he was in fact like us in every way but sin and came into contact with such unwelcome aggressors.

Such speculations, however, do not in and of themselves prove anything. While present-day biological insights cannot tell us definitively which diseases Christ suffered from or even whether he suffered at all from any diseases—for who knows the answer to such a puzzling question which neither Scripture nor Apostolic testimony provide an answer?—the contemporary understanding of the nature of bacteria and viruses leads the modern believer and theologian with his improved knowledge of the workings of the world to re-examine anew the state of the question. If God in his infinite wisdom saw it fitting to suffer and die at the hands of his Roman aggressors, as well as the bodily defects of hunger and thirst, for the sake of satisfaction, convincibility, and exemplarity, as Thomas Aquinas reasons, then why should he not also see it fitting to suffer at the “hands” of those more hidden, smaller foes in the form of bacteria and viruses, whose actions are no less external and foreign to his most sacred body? For Christ’s body to struggle against a virus, for example, does not demonstrate weakness or imperfection but instead indicates that his body is healthy and is responding accordingly to the presence of a harmful foreign entity.

One can maintain simultaneously that Christ had the perfections of body, soul, knowledge, and grace, and that he also experienced bodily suffering as the result of certain diseases or illnesses. The contradiction that Thomas thought he saw as a result of his own contemporary understanding of biology does not actually exist in every instance of disease, and so while it is not possible on this side of heaven to know whether Christ in fact suffered from disease or illness, it is not as unfitting as it was previously thought. Instead, by returning to the reasons that Thomas himself provided to justify the fittingness of Christ being susceptible to death, hunger, and thirst, one sees that it is equally fitting that Christ experienced fevers, the occasional sore throat and runny nose, or even some of the more serious illnesses that result from harmful foreign entities without at the same time positing that he could have suffered death from them, since his body was perfect in its ability to fight off such unwelcome diseases. After all, would not such sufferings of Christ widen the scope of the fullness of his satisfaction; the convincibility that he was fully human beyond simple hunger, thirst and his ability to die on the Cross; and provide an even more complete example of patience and strength in the midst of suffering, even if it was at the “hands” of the less obvious and perceptible of aggressors?

[1] Athanasius, On the Incarnation, Translated by John Behr (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Press, 2011), 72.